полная версия

полная версияThe History of the Hen Fever. A Humorous Record

Never was a grosser hum promulgated than this was, from beginning to end, even in the notorious hum of the hen-trade. There was absolutely nothing whatever in it, about it, or connected with it, that possessed the first shade of substance to recommend it, saving its name. And this could not have saved it, but from the fact that nobody (not even the originator of the unpronounceable cognomen himself) was ever able to write or spell it twice in the same manner.

The variety of fowl itself was the Grey Chittagong, to which allusion has already been made, and the first samples of which I obtained from "Asa Rugg" (Dr. Kerr), of Philadelphia, in 1850. Of this no one now entertains a doubt. They were the identical fowl, all over, – size, plumage and characteristics.

But my friend the Doctor wanted to put forth something that would take better than his "Plymouth Rocks;" and so he consulted me as to a name for a brace of grey fowls I saw in his yard. I always objected to the multiplying of titles; but he insisted, and finally entered them at our Fitchburg Dépôt Show as "Burrampooters," all the way from India.

These three fowls were bred from Asa Rugg's Grey Chittagong cock, with a yellow Shanghae hen, in Plymouth, Mass. They were an evident cross, all three of them having a top-knot! But, n'importe. They were then "Burrampooters."

Subsequently, these fowls came to be called "Buram-pootras," "Burram Putras," "Brama-pooters," "Brahmas," "Brama Puters," "Brama Poutras," and at last "Brahma Pootras." In the mean time, they were advertised to be exhibited at various fairs in different parts of the country under the above changes of title, varied in certain instances as follows: "Burma Porters," "Bahama Paduas," "Bohemia Prudas," "Bahama Pudras." And, for these three last named, prizes were actually offered at a Maryland fair, in 1851!

The following capital sketch (which appeared originally in the Boston Carpet-Bag) is from the pen of the late Secretary of the Mutual Admiration Society, – a gentleman, and a very happy writer in his way. It gives a faithful and accurate description of what many of these monsters really were, and will be read with gusto by all who have now come to be "posted up" in the secrets of the hen-trade.

The editor of the above-named journal remarks that "as our Carpet-Bag contains something connected with everything under the sun, we have abstracted therefrom a chapter on chicken-craft, which embraces a very important detail of that most abstruse science. When our readers scan the beautiful proportions of the stately fowl that roosts at the head of this article, they will acknowledge that we have some right to cackle because of the good fortune we have had in securing such an uneggsceptionable picture, exhibiting the very perfection of cockadoodledom. Isn't he a beauty, this Bother'em Pootrum?

"Examine his altitude! Observe the bold courage that stands forth in his every lineament! There is no dunghill bravery there! See what symmetry floats round every detail of his noble proportions! What kingly grace associates with the comb that adorns his head as it were a crown! What fire there is in his eye! With what proud bearing does he not wear his abbreviated posterior appendage! Looking at the latter, we, and every one knowing in hen-craft, will readily exclaim, 'Gerenau de Montbeillard! you must have been a most unmitigated muff to designate that beautiful fowl the gallus ecaudatus, or tailless rooster.' For ourselves, our indignity teaches us to say, 'Mons. M.! your Essai sur Historie Nat. des Gallinacæ Fran. tom. ii., pp. 550 et 656, is a humbug!' We know that the universal world will sympathize in our sentiment on this point."

Peter Snooks, Esq. (a correspondent of this journal), it appears, had the honor to be the fortunate possessor of this invaluable variety of fancy poultry, in its unadulterated purity of blood. He furnished from his own yard samples of this rare and desirable stock for His Royal Highness Prince Albert, and also sent samples to several other noted potentates, whose taste was acknowledged to be unquestionable, including the King of Roratonga, the Rajah of Gabble-squash, His Majesty of the Cannibal Islands, and the Mosquito King. Peter supplies the annexed description of the superior properties of this variety of fowls:

"The Bother'em Pootrums are generally hatched from eggs. The original pair were not; they were sent from India, by way of Nantucket, in a whale-ship.

"They are a singularly pictur-squee fowl from the very shell. Imagine a crate-full of lean, plucked chickens, taking leg-bail for their liberty, and persevering around Faneuil Hall at the rate of five miles an hour, and you have an idea of their extremely ornamental appearance.

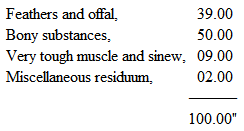

"They are remarkable for producing bone, and as remarkable for producing offal. I have had one analyzed lately by a celebrated chemist, with the following result:

A peculiarly well-developed faculty in this extraordinary fine breed of domestic fowls is that of eating. "A tolerably well-fed Bother'em will dispose of as much corn as a common horse," insists Mr. S – . This goes beyond me; for I have found that they could be kept on the allowance, ordinarily, that I appropriated daily to the same number of good-sized store hogs. As to affording them all they would eat, I never did that. O, no! I am pretty well off, pecuniarily, but not rich enough to attempt any such fool-hardy experiment as that!

But Snooks is correct about one thing. They are not fastidious or "particular about what they eat." Whatever is portable to them is adapted to their taste for devouring. Old hats, India-rubbers, boots and shoes, or stray socks, are not out-of-the-way fare with them. They are amazingly fond of corn, especially a good deal of it. They will eat wheaten bread, rather than want.

They are very inquisitive in their nature. Their habit of stalking around the dwelling-house, and popping their heads into the garret-windows, is evidence of this peculiar trait.

Their flesh is firm and compact, and requires a great deal of eating to do it justice. Like Barney Bradley's leather "O-no-we-never-mention-'ems," when cut up and stewed for tripe, "a fellow could eat a whole bushel of potatoes to the plateful." It is of the color of a stale red herring, and very much like that edible in taste. Its scarcity constitutes its value.

This rara avis in terris grows to a height somewhere between .00 feet .16 inches and 25 feet. Its weight somewhat between .06 pounds and 1 cwt. It never lays, except when it rolls itself in the sand. The female fowls sometimes do that duty, though amazingly seldom.

Mr. Snooks says he will back his Bother'em, for a chicken-feast, to outcrow any three asthmatical steam-whistles that any railroad company can scare up; and adds, "I am ashamed of the prejudice which makes my fellow-men unjust. The Fowl Society – the New England organization, I mean – repudiate the special merits of my Bother'em Pootrums, and tell me that their ideas of improvement go entirely contrary to the propriety of tolerating my noble breed of fowls. Disgustibus non disputandum, as Shakspeare, or somebody for him, emphatically says, – which means, 'Every one to his taste, as the old lady said when she kissed the cow.' One thing it will not be hard to prove, I think; that is, simply the probability of something like envy operating among the members of the Hen Society, on account of the exclusive attention paid my Bother'ems at the late Fowl Fairs in Boston," – where the 'squire's contributions did rather "astonish the boys" who were not thoroughly acquainted with the excellent qualities of these birds. Verily, Snooks' "Bother'ems" did bother 'em exceedingly!

CHAPTER XV.

ADVERTISING EXTRAORDINARY

From the outset of my experience in the final attack of the hen fever, I took advantage of every possible opportunity to disseminate the now world-wide known fact that nobody else but myself possessed any "pure-bred" poultry! I could have proved this by the affidavits of more than a thousand "disinterested witnesses," at any time after April and May, 1851, had I been called upon so to do. But as no one doubted this, there was then no controversy.

But, as time wore along, competition became rife, and the foremost chicken-raisers began to look about them for the readiest means obtainable with which to cut each other's throats; not "with a feather," by any means, because that would have "smelt of the shop;" but whenever, wherever, or however, their neighbors could be traduced, maligned, vilified, or injured (in this pursuit), they embraced the opportunity, and followed it up, without stint, especially towards my humble self, until most of them, fortunately, broke their own backs, and were compelled to retire from the field, while "the people" grinned, and comforted them with the friendly assurance that it "sarved 'em right."

At the Fitchburg Dépôt Show, in 1850, my original "Grey Chittagongs" (already described) were in the possession of G.W. George, Esq., of Haverhill, to whom they had been sold by the party to whom I had previously sold them. Nobody thought well of them; but they took a first prize there, and the "Chittagongs" (so entered at the same time) of Mr. Hatch, of Connecticut, also took a prize. My friend the Doctor then insisted that these were also "Burrampooters;" but, as nobody but himself could pronounce this jaw-cracking name, it was taken little notice of at that time.

Mr. Hatch had a large quantity of the Greys at this show, which sold readily at $12 to $20 the pair; and immediately after this exhibition the demand for "Grey Chittagongs" was very active. I watched the current of the stream, and I beheld with earnest sympathy the now alarming symptoms of the fever. "The people" had suffered a relapse in the disease, and the ravages now promised to become frightful – for a time!

An ambitious sea-captain arrived at New York from Shanghae, bringing with him about a hundred China fowls, of all colors, grades, and proportions. Out of this lot I selected a few grey birds, that were very large, and (consequently) "very fine," of course. I bred these, with other grey stock I had, at once, and soon had a fine lot of birds to dispose of – to which I gave what I have always deemed their only true and appropriate title (as they came from Shanghae), to wit, Grey Shanghaes.

In 1851 and '52 I had a most excellent "run of luck" with these birds. I distributed them all over the country, and obtained very fair prices for them; and, finally, the idea occurred to me that a present of a few of the choicest of these birds to the Queen of England wouldn't prove a very bad advertisement for me in this line. I had already reaped the full benefit accruing from this sort of "disinterested generosity" on my part, toward certain American notables (whose letters have already been read in these pages), and I put my newly-conceived plan into execution forthwith.

I then had on hand a fine lot of fowls, bred from my "imported" stock, which had been so much admired, and I selected from my best "Grey Shanghae" chickens nine beautiful birds. They were placed in a very handsome black-walnut-framed cage, and after having been duly lauded by several first-rate notices in the Boston and New York papers, they were duly shipped, through Edwards, Sanford & Co.'s Transatlantic Express, across the big pond, addressed in purple and gold as follows:

TO H.M.G. MAJESTY,VICTORIA,QUEEN OF GREAT BRITAINTo be Delivered at Zoological Gardens,LONDON, ENG—FROM GEO. P. BURNHAM, BOSTON, MASS., U.S.AThe fowls left me in December, 1852. The London Illustrated News of January 22d, 1853, contained the following article in reference to this consignment:

"By the last steamer from the United States, a cage of very choice domestic fowls was brought to Her Majesty Queen Victoria, a present from George P. Burnham, Esq., of Boston, Mass. The consignment embraced nine beautiful birds – two males and seven pullets, bred from stock imported by Mr. Burnham direct from China. The fowls are seven and eight months old, but are of mammoth proportions and exquisite plumage – light silvery-grey bodies, approaching white, delicately traced and pencilled with black upon the neck-hackles and tips of the wings and tails. The parent stock of these extraordinary fowls weigh at maturity upwards of twenty-three pounds per pair; while their form, notwithstanding this great weight, is unexceptionable. They possess all the rotundity and beauty of the Dorking fowl; and, at the same age, nearly double the weight of the latter. They are denominated Grey Shanghaes (in contradistinction to the Red or Yellow Shanghaes), and are considered in America the finest of all the great Chinese varieties. That they are a distinct race, is evident from the accuracy with which they breed, and the very close similarity that is shown amongst them; the whole of these birds being almost precisely alike, in form, plumage and general characteristics. They are said to be the most prolific of all the Chinese fowls. At the time of their shipment, these birds weighed about twenty pounds the pair."

This was a very good beginning. In another place (see page 88) I have given a copy of the letter from Hon. Col. Phipps, her Majesty's Secretary of the Privy Purse, acknowledging the receipt of this present. A few weeks afterward, the London News contained a spirited original picture of seven of the nine Grey Shanghae fowls which I had the honor to forward to Queen Victoria. The drawing was made by permission of the Queen, at the royal poultry-house, from life, by the celebrated Weir, and the engraving was admirably executed by Smythe, of London. The effect in the picture was capital, and the likenesses very truthful. In reference to these birds, the News has the following:

"Grey Shanghae Fowls for Her Majesty. – In the London Illustrated News for January 22d, we described a cage of very choice domestic fowls, bred from stock imported by Mr. George P. Burnham, of Boston, Mass., direct from China, and presented by him to Her Majesty. We now engrave, by permission, these beautiful birds. They very closely resemble the breed of Cochin-Chinas already introduced into this country, the head and neck being the same; the legs are yellow and feathered; the carriage very similar, but the tail being more upright than in the generality of Cochins. The color is creamy white, slightly splashed with light straw-color, with the exception of the tail, which is black, and the hackles, which are pencilled with black. The egg is the same color and form as that of the Cochins hitherto naturalized in this country. These fowls are very good layers, and have been supplying the royal table since their reception at the poultry-house, at Windsor."

All this "helped the cause along" amazingly. It proved a most excellent mode of advertising my "superb," "magnificent," "splendid," "unsurpassable," "inapproachable" Grey Shanghaes.

The above articles found their way (somehow or other) into the papers of this country immediately; and, within sixty days afterwards, the price of "Bother'ems" went up from $12 and $15 to $50, $75, $100, and $150, the pair!!

"Cochin-Chinas" were now nowhar! But I was so as to be about yet.

CHAPTER XVI.

HEIGHT OF THE FEVER

While this cage of Grey Shanghaes stood for an hour or two in the express-office of Adams & Co., in Boston, a servant came from the Revere House to inform me that "a gentleman desired to see me there, about some poultry."

As I never had had occasion to run round much after my customers, and, moreover, as I felt that the dignity of the business – (the dignity of the hen-trade!) – might possibly be compromised by my responding in person to this summons, I directed the servant to "say to the gentleman, if he wished to see me, that I should be at my office, No. 26 Washington-street, for a couple of hours, – after that, at my residence in Melrose."

The man retired, and half an hour afterwards a carriage stopped before my office-door. The gentleman was inside. He invited me to ride with him – (I could afford to ride with him) – to Adams & Co.'s office. He had seen the "Grey Shanghaes" intended for the Queen there.

"I want that cage of fowls," he said.

"My dear sir," I replied, "they are going to England."

"I want them. What will you take for them?"

"I can't sell them, sir."

"You can send others, you know."

"No, sir. I can't dispose of these, surely."

"Can you duplicate this lot?"

"Pretty nearly – perhaps not quite."

"I see," he continued. "I will give you two hundred dollars for them."

"No, sir."

"Three hundred – come!"

"I can't sell them."

"Will you take four hundred dollars for the nine chickens, sir?" he asked, drawing his pocket-book in presence of a dozen witnesses.

I declined, of course. I couldn't sell these identical fowls; for I had an object in view, in sending them abroad, which appeared to me of more consequence than the amount offered – a good deal.

"Will you name a price for them?" insisted the stranger.

I said, "No, sir – excuse me. I would not take a thousand dollars for these birds, I assure you. Their equals in quality and number do not live, I think, to-day, in America!"

"I won't give a – a – thousand dollars, for them," he said, slowly. "No, I won't give that!" and we parted. Yet, I have no doubt, had I encouraged him with a prospect of his obtaining them at all, he would have given me a thousand dollars for that very cage of fowls! To this extent did the hen fever rage at that moment.

I subsequently sent this gentleman two trios of my grey chickens, for which he paid me $200.

And now the Grey Shanghae trade commenced in earnest. Immediately after the announcements were made (which I have quoted) orders poured in upon me furiously from all quarters of this country, and from Great Britain. Not a steamer left America for England, for months and months, on board of which I did not send more or less of the "Grey Shanghaes." From every State in the Union, my orders were large and numerous; and letters like the following were received by me almost every day, for months:

"G.P. Burnham.

"Sir: I have just seen the pair of superb Grey Shanghae fowls which you sent to Mr. – , of this city, and I want a pair like them. If you can send me better ones, I am willing to pay higher for them. He informs me that your price per pair is forty dollars. I enclose you fifty dollars; do the best you can for me, but forward them at once, – don't delay.

Yours, &c.," – ."I almost always had "better ones." That was the kind I always kept behind, or for my own use. I rarely sent away these better ones until they cried for 'em! I always had a great many of the "best" ones, too; which were even better than those "better" ones for which the demand had come to be so great!

Strange to say, everybody got to want better ones, at last; and, finally, I had none upon my premises but this very class of birds – to wit, the "better ones." To be sure, I reserved a very few pairs of the best ones, which could be obtained at a fair price; but these were the ones that would "take down" the fanciers, occasionally, who wanted to beat me with them at the first show that came off. But I didn't sleep much over this business. I always had one cock and three or four hens that the boys didn't see– until we got upon the show-ground. Ha, ha!

A stranger called at my house, one Sunday morning, just as I was ready with my family for church. He apologized for coming on that day, but couldn't get away during the week. He had never seen the Grey Shanghaes – didn't know what a Chinese fowl was – had no idea about them at all. He wanted a few eggs – heard I had them – wouldn't stop but a moment – saw that I was just going out, &c. &c. He sat down – was sorry to trouble me – wouldn't do so again – would like just to take a peep at the fowls – when, suddenly, as he sat with his back close to the open window, my old crower sent forth one of those thundering, unearthly, rolling, guttural shrieks, that, once heard, can never be forgotten!

The stranger leaped from his chair, and sprang over his hat, as he yelled,

"Good God! what's that?"

His face was as white as his shirt-bosom.

"That's one of the Grey Shanghaes, crowing," I replied.

"Crow! I beg your pardon," he said; "I don't want any eggs – no! I'll leave it to another time. I – a – I couldn't take 'em now; won't detain you – good-morning, sir," he continued; and, rushing out of my front door, he disappeared on "a dead run," as fast as his legs could carry him. And I don't know but he is running yet. He was desperately alarmed, surely!

I was so amused at this incident, that I was in a precious poor mood to attend church that morning. And when my friend the minister arose at length, and announced for his text that "the wicked flee when no man pursueth," those words capped the climax for me.

I jammed my handkerchief into my mouth, until I was nearly suffocated, as I thought of that wicked fellow who had just been so frightened while in the act of attempting to bargain for fancy hen's eggs on the Sabbath!

A Western paper, in alluding to the fever, about this period, observed that "this modern epidemic has shown itself in our vicinity within a short time, and is characterized by all the peculiarities which have marked its ravages elsewhere. Some of our most valuable citizens are now suffering from its attacks, and there is no little anxiety felt for their recovery. The morning slumbers of our neighbors are interrupted by the sonorous and deep-toned notes of our Shanghae Chanticleer, and various have been the inquiries as to how he took 'cold,' and what we gave him for it. 'Chittagongs' and 'Burma Porters' are now as learnedly discussed as 'Fancy Stocks' on change.

The N.Y. Scientific American stated, at this time, that the "Cochin-China fowl fever was then as strong in England as in some parts of New England, – in fact, stronger. One pair exhibited there was valued at $700. What a sum for a hen and rooster! The common price of a pair is $100," added this journal; and still the trade continued excellent with me.

CHAPTER XVII.

RUNNING IT INTO THE GROUND

There now seemed to be no limit whatever to the prices that fanciers would pay for what were deemed the best samples of fowls. For my own part, from the very commencement I had been considerate and merciful in my charges. True, I had been taken down handsomely by a Briton (in my original purchase of Cochin-Chinas), but I did not retaliate. I was content with a fair remuneration; my object, principally, was to disseminate good stock among "the people," for I was a democrat, and loved the dear people.

So I charged lightly for my "magnificent" samples, while other persons were selling second and third rate stock for five or even six and eight dollars a pair. The "Grey Shanghaes" had got to be a "fixed fact" in England, as well as in this country, and still I was flooded with orders continually.

I obtained $25, $50, $100 a pair, for mine; and one gentleman, who ordered four greys, soon after the Queen's stock reached England, paid me sixty guineas for them – $150 a pair. But these were of the better class of birds to which I have alluded.

In 1852 a Boston agricultural journal stated that "within three months extra samples of two-year-old fowls, of the large Chinese varieties, have been sold in Massachusetts at $100 the pair. Several pairs, within our own knowledge, have commanded $50 a pair, within the past six months. Last week we saw a trio of White Shanghaes sold in Boston for $45. And the best specimens of Shanghaes and Cochin-China fowls now bring $20 to $25 a pair, readily, to purchasers at the South and West."