полная версия

полная версияThe History of the Hen Fever. A Humorous Record

In New England, especially, prior to the second show of poultry in Boston, the fever had got well up to "concert pitch;" and in New York State "the people" were getting to be very comfortably interested in the subject – where my stock, by this time, had come to be pretty extensively known.

The expenses attendant upon this part of the business, to wit, the process of furnishing the requisite amount of information for "the people" (on a subject of such manifestly great importance), the quantum sufficit in the way of drawings, pictures, advertisements, puffings, etc., through the medium of the press, can be imagined, not described.

The cost of the drawings and engravings which I had executed for the press, from time to time, during the years 1850, '51, '52, and '53, exceeded over eight hundred dollars; but this, with the descriptions of my "rare" stock (which I usually furnished the papers, accompanying the cuts), was my chosen mode of advertising. And I take this method publicly to acknowledge my indebtedness to the press for the kindness with which I was almost uniformly treated, while I was thus seriously affected by the epidemic which destroyed so many older and graver men than myself; though few who survived the attack "suffered" more seriously than I did, during the course of the fever. For instance, the large picture of the fowls which I had the pleasure of sending to Her Majesty Queen Victoria (in 1852), and which appeared in Gleason's Pictorial, the New York Spirit of the Times, New England Cultivator, &c., cost me, for the original drawing, engraving, electrotyping, and duplicating, eighty-three dollars.

All these expenses were cheerfully paid, however, because I found my reward in the consciousness that I performed the duty I owed to my fellow-men, by thus aiding (in my humble way) in disseminating the information which "the people" were at that time so ravenously in search of, namely, as to the person of whom they could obtain (without regard to price) the best fowls in the country.

This was what "the people" wanted; and thus the malady extended far and wide, and when the fall of 1850 arrived, buyers had got to be as plenty as blackberries in August, whilst sellers "of reputation" were, like the visits of angels, few and far between. I was, by this time, considered "one of 'em." I strove, however, to carry my honors with Christian meekness and forbearance, and with that becoming consideration for the wants and the wishes of my fellow-men that rendered myself and my "purely-bred stock" so universally popular.

Ah! when I look back on the past, – when I reflect upon the noble generosity and disinterestedness that characterized all my transactions at that flush period, – when I think of what I did for "the cause," and how liberally I was rewarded for my candor, my honesty of purpose, and my disingenuousness, – tears of gratitude and wonder rush to my eyes, and my overcharged heart only finds its solace by turning to my ledger and reading over, again and again, the list of prices that were then paid me by "the people," week after week, and month after month, for my "magnificent samples" of "pure-bred" Cochin-China chickens, the original of which I had imported, and which were said to have been bred from the stock of the Queen of Great Britain.

But, the Mutual Admiration – I mean, the "Society" whose name was like

"Lengthened sweetness, long drawn out,"

was about to hold its second annual exhibition; and, as the number of its members had largely increased, and as each and all of those who pulled the wires of this concern (while at the same time they were pulling the wool over the eyes of "the people") had plans of their own in reference to details, I made up my mind, although I felt big enough to stand up even in this huge hornet's nest of competition, to have things to suit my "notions."

I now had fowls to sell! I had raised a large quantity of chickens; winter was approaching, corn was high, they required shelter, the roup had destroyed scores of fowls for my neighbors, and I didn't care to winter over three or four hundred of these "splendid" and "mammoth" specimens of ornithology, each one of which could very cleverly dispose of more grain, in the same number of months, than would serve to keep one of my heifers in tolerable trim.

Such restrictions were proposed by the officers of the Society with the lengthened cognomen, that my naturally democratic disposition revolted against the arbitrary measures talked of, and I resolved to get up an exhibition of my own, where this matter could be talked over at leisure, and which I did not doubt would "turn an honest penny" into my own pocket; where, though I had done well thus far, there was still room, as there was in hungry Oliver Twist's belly, for "more."

CHAPTER IX.

THE SECOND POULTRY-SHOW IN BOSTON

On the 2d, 3d, and 4th days of October, in the year of our Lord 1850, the "grand exhibition" (so the Report termed it), for that year, came off at the large hall over the Fitchburg Railroad Dépôt, in Boston, "which proved a most extensive and inviting one" (so continued the Report), "far exceeding, both in numbers and in the quality of specimens offered, anything of its kind ever got up in America.

"The birds looked remarkably fine in every respect, and the undertaking was very successful. A magnificent show of the feathered tribe greeted the thousands of visitors who called at the hall, and all parties expressed their satisfaction at the proceedings.

"The Committee awarded to George P. Burnham, of Melrose, the first premiums for fowls and chickens. The prize birds were the 'Royal Cochin-Chinas' and their progeny, which have been bred with care from his imported stock; and which were generally acknowledged at the head of the list of specimens."

The prices obtained at this exhibition ranged very high, and "full houses" were constantly in attendance, day and evening, to examine and select and purchase from the "pure-bred" stock there. "Mr. Burnham, of Melrose" (continued the Report), "declined an offer of $120 for his twelve premium Cochin-China chickens, and subsequently refused $20 for the choice of the pullets."

"The show was much larger than the first one, and the character of the birds exhibited was altogether finer, though the old fowls were, for the most part, moulting. A deep interest was manifested in this enterprise, and it went off with satisfaction to all concerned," added the Report.

In order that the details of this experiment (which I projected and carried through, myself) may be appreciated and understood, I extract from the "official" Report the following items regarding this show, the expenses, the prize-takers, &c.

The "Committee of Judges," consisting of myself, G.P. Burnham, Esq., and a gentleman of Melrose, made the following statements and "observations," in the Report above referred to:

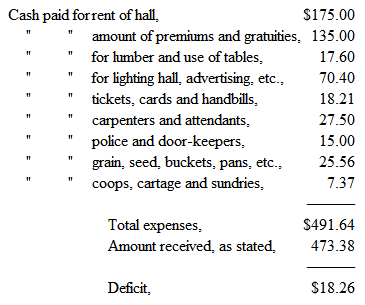

"The Exhibition was visited by full ten thousand persons, during the three days mentioned. The amount of money received for tickets was four hundred and seventy-three dollars and thirty-eight cents; and the following disbursements were made:

When the state of the funds was subsequently more particularly inquired into, however, it was found that the amount of money actually received at the door was a little rising nine hundred and seventy dollars, instead of "four hundred and seventy-three," as above quoted. But this was a trifling matter; since the "Committee of Judges" spoken of above accounted for this sum, duly, in the final settlement.

The "Committee" aforesaid awarded the following premiums at this show, after attending to the examination confided to them – namely:

"First premium, for the best six fowls contributed, to George P. Burnham, of Melrose, Mass., $10.

"For the three best Cochin-China Fowls (Royal), to George P. Burnham, Melrose, Mass., $5.

"For the twelve best chickens, of this year's growth (Royal Cochin-China), to George P. Burnham, Melrose, $5."

And there were some other premiums awarded, I believe, there, but by which I was not particularly benefited; and so I pass by this matter without further remark, entertaining no doubt whatever that all the gentlemen who were awarded premiums (and who obtained the amount of the awards) exhibited at the Fitchburg Hall Show pure-bred fowls.

After making these awards, the "Committee of Judges" (consisting, as aforesaid, of myself, Mr. Burnham, and a fancier from Melrose) state that "they find great pleasure" – (mark this!) – "they find great pleasure in alluding again to the splendid contributions" of some of the gentlemen who had fowls in this show, – and then the Report continues as follows:

"The magnificent samples of Cochin-China fowls, contributed by G.P. Burnham, of Melrose, were the theme of much comment and deserved praise. These birds include his imported fowls and their progeny – of which he exhibited nineteen splendid specimens. To this stock the Committee unanimously awarded the first premiums for fowls and chickens; and finer samples of domestic birds will rarely be found in this country. They are bred from the Queen's variety, obtained by Mr. Burnham last winter, at heavy cost, through J. Joseph Nolan, Esq., of Dublin, and are unquestionably, at this time, the finest thorough-bred Cochin-Chinas in America."

My early hen-friend the "Doctor" – alluded to in the opening chapter of this book – exhibited a fowl which the "Committee" thus described in their report:

"The rare and beautiful imported Wild India Game hen, contributed by Mr. B.F. Griggs, Columbus, Geo., was a curiosity much admired. This fowl (lately sold by Dr. J.C. Bennett, of Plymouth, to Mr. Griggs, for $120) is thorough game, without doubt; and her progeny, exhibited by Dr. Bennett, were very beautiful specimens. To this bird, and the 'Yankee Games' of Dr. Bennett, the Committee awarded a gratuity of $5."

So miserable a hum as this was, I never met with, in all my long Shanghae experience. It out-bothered the Doctor's famous "Bother'ems," and really out-Cochined even my noted Cochin-Chinas! But I was content, I was one of the "Committee of Judges." I had forgot!

This Committee's Report was thus closed:

"It has been the aim of the Committee to do justice to all who have taken an interest in the late Fowl Exhibition, and they congratulate the gentlemen who have sustained this enterprise upon its success."

They did ample justice to this Wild Bengal Injun Hen, that is certain. The Cochin-China trade received an impulse (after this show concluded) that astonished even me, and I am not easily disturbed in this traffic. And I have no doubt that the people who paid their money to witness this never-to-be-forgotten (by me) exhibition, were also satisfied.

The experiment was perfectly successful, however, throughout. I forwarded to all my patrons and friends copies of this Report, beautifully illustrated; and the orders for "pure-bred chickens from the premium stock" rushed in upon me, for the next four or five months, with renewed vigor and spirit.

This first exhibition at the Fitchburg Dépôt Hall proved to me a satisfactorily profitable advertisement, as I carried away all the premiums there that were of any value to anybody. But then it will be observed that the "Committee of Judges" of this show were my "friends." And, at that time, the competition had got to be such that all the dealers acted upon the general democratic principle of going "for the greatest good of the greatest number." In my case, I considered the "greatest number" Number One!

CHAPTER X.

THE MUTUAL ADMIRATION SOCIETY'S SECOND SHOW

In the month following, to wit, on the 12th, 13th and 14th of November, 1850, the second annual exhibition of the Simon Pure Society with the extended title was held at the Public Garden, in Boston.

No premiums were offered by the society this year, and there wasn't much to labor for. I was a contributor, and I believe I was elected a member of the Committee of Judges that year. How, I did not know. At any rate, I wrote the published Report upon the exhibition. A Mr. Sanford Howard was chairman of this committee, if I remember rightly; and though undoubtedly a very respectable and well-meaning man (if he had not been so, he wouldn't have been placed on a Committee of Judges with me, I imagine), this Mr. Howard knew positively nothing whatever in regard to the merits or faults of poultry generally. He had acquired some vague notions about what he was pleased to term "crested" fowls, and five-toed, white-legged, white-plumed, white-billed, white-bellied Dorkings, – of which he conversed technically and learnedly; but as to his knowledge of the different varieties and breeds of domestic poultry then current, and their characteristics, it was evidently warped and very limited.

But Mr. Howard had been connected for some months with a small monthly publication in New York State, and, like myself, I presume, among the board (God knows who they were, but I don't, and never did!) who originally chose this "Committee," he had "a friend at court," and was made chairman of the committee too, —how, I never knew, either.

In their Report, the Committee observe, again, that "never in this country, if in the world, was there collected together so large a number of domestic fowls and birds as were sent to this exhibition, probably; and, though the most liberal arrangements were made in advance, it was found that the accommodations, calculated for ten thousand specimens, were entirely insufficient. The Committee merely allude to this fact to show the actual extent of this enterprise, and the importance which the undertaking has assumed, in a single year from the birth of the Association.

"According to the records of the Secretary, there were contributed to the Society's exhibition of 1850 some four hundred and eighty coops and cages. There were in all over three hundred and fifty contributors; in addition to which about forty coops, containing some six hundred fowls, were sent to the Garden and received on exhibition upon the two last days of the Show; and which could not be recorded agreeably with the regulations made originally.

"The palpable improvement in the appearance of the fowls exhibited in 1850, as compared with the samples shown in 1849, offers ample encouragement to breeders for further and more extended efforts; and your Committee would urge it upon those who have already shown themselves competent to do so much, to go on and effect still greater progress in the improvement of the poultry of New England."

This Report (the second of the series) did my stock ample justice, I have not a doubt. I wrote it myself, and intended that it should do so. The text was in nowise changed when printed, and a reference to the document (for that year) will convince the skeptical – if any exist – whether I was or was not acquainted with adjectives in the superlative degree!

A very singular occurrence took place about this time, the basis of which I did not then, and have never since, been able to comprehend, upon any principles of philosophy, economy, business, benevolence, or even of sanity. But I am not very clear-headed.

In the addenda to my Report (above named) there appeared the annexed statement, by somebody:

"The Trustees refer to the following with mixed pride and pleasure; the munificence and motive of the gift are most creditable. A voluntary kindness such as that of Mr. Smith is a very gratifying proof that the labors of the Society are not regarded by enlightened men as vain:

"Boston, 12th February, 1851."G.W. Smith, Esq.

"Sir: A meeting of the Trustees of the 'New England Society for the Improvement of Domestic Poultry' was held last evening, Col. Samuel Jaques, President of the Society, in the chair, and a full quorum being present, when the Treasurer announced the receipt of your very handsome donation of one hundred and fifty dollars in aid of the Society's funds; whereupon it was moved, and unanimously agreed, that the most grateful thanks of the Society were justly due to you for such a munificent testimony of your desire for its prosperity; that the Secretary communicate to you the assurance of the high appreciation with which the donation was received; and that its receipt, and also a thankful expression of gratitude towards you, should be placed on the records of the Society.

"I can only reiterate the sentiments contained in my instructions, in which I fully and gratefully concur; and, with best wishes for your long-continued welfare,

"I am, sir, very truly yours,"John C. Moore, Rec. Secretary."Now, it will be observed that this was not John Smith who presented this sum, but another gentleman, and a different sort of individual altogether. He gave it (one hundred and fifty dollars in hard cash) the full value of a nice pair of my best "pure-bred" Cochin-Chinas, without flinching, without any fuss, outright, freely, "in aid of the Society's funds."

Liberal, generous, benevolent, charitable, kindly Mr. Smith! You did yourself honor! You were one of the kind of men that I should very much liked to have had for a customer, about those days. But, after due inquiry, I ascertained that you did not keep, or breed, poultry. You were only a "friend" to the Society with the elongated name, – the only friend, by the way, it ever had! Heaven will reward you, Mr. Smith, sooner or later, for your disinterestedness, but the Society never can. Be patient, however, and console yourself with the reflection that he who giveth to the poor, lendeth, &c. &c. The Society with the long-winded title was poor enough, and you cannot have forgotten that he who casteth his bread (or money) upon the waters will find it, after many days. You will find yours again, I have no doubt; but it will be emphatically "after many days."

The second show closed, the expenses of which reached the sum of one thousand and twenty-seven dollars eighteen cents, and the receipts at which amounted to one thousand and seventy-nine dollars eighty-four cents, exclusive of the above-named donation. The Society had now a balance of two hundred and two dollars sixty-six cents in hand, and it went on its way rejoicing.

Col. Jaques (the first President) now "resigned his commission," and Moses Kimball, Esq., was chosen in his stead. I found myself once more among the Vice Presidents, John C. Moore was elected Secretary, Dr. Eben Wight was made Chairman of the Board of Trustees, and H.L. Devereux became Treasurer for the succeeding year.

These officers were all "honorable men" who were thus placed in position to watch each other! The delightful consequences can readily be fancied. What my own duties were (as Vice-President) I never knew. I supposed, however, that, as "one of 'em" thus elevated in official rank, I was expected to do my uttermost to keep the bubble floating, and to aid, in my humble way, to maintain the inflation. And I acted accordingly; performing my duty "as I understood it"!

CHAPTER XI.

PROGRESS OF THE MALADY

Immediately after this second exhibition, the sales of poultry largely increased. Everybody had now got fairly under weigh in the hen-trade; and in every town, at every corner, the pedestrian tumbled over either a fowl-raiser or some huge specimen of unnameable monster in chicken shape.

I had been busy, and had added largely to my "superior" stock of "pure-blooded" birds, by importations from Calcutta, Hong-Kong, Canton and Shanghae, direct. In two instances I sent out for them expressly, and in two or three other instances I had obtained them directly from on shipboard, as vessels arrived into Boston and New York harbors.

I was then an officer in the Boston Custom-house, – a democrat under a whig collector, – otherwise, a live skinned eel in a hot frying-pan. But I found that my business had got to be such that I could not fulfil my duty to Uncle Sam and attend appropriately to what had now got to be of very much greater importance to me; and so I resigned my situation as Permit Clerk at the public stores, very much to the regret of everybody in and out of the Custom-house, and especially those who were applicants for my place!

I had purchased a pretty estate in Melrose, and now I enlarged my premises, added to my stock, and raised (during the summer and fall of 1851) over a thousand fowls, upon my premises. This did not begin to supply the demands of my customers, however, or even approach it. And, to give an idea of my trade at that period, I will here quote a letter from one of my new patrons. It came from the interior of Louisiana, in the fall of 1851.

"Geo. P. Burnham, Esq., Boston.

"I am about to embark in the raising of poultry, and I hear of yourself as an extensive breeder in this line. Do me the favor to inform me, by return mail, what you can send me one hundred pairs of Chinese fowls for, of the yellow, red, white, brown and black varieties; the cocks to be not less than eight to ten months old, and pullets ready to lay; say twenty pairs of each color. And also state how I shall remit you, in case your price suits me, &c.

" – ."I informed this gentleman that I had just what he wanted (of course), and that if he would remit me a draft by mail for fifteen hundred dollars – though this price was really too low for them – I would forward him one hundred pairs of fowls "that would astonish him and his neighbors." Within three weeks from the date of my reply to him, I received a sight draft from the Bank of Louisiana upon the Merchants' Bank, Boston, for fifteen hundred dollars. I sent him such an invoice of fowls as pleased him, and I have no doubt he was (as he seemed to be) perfectly satisfied that he had thus made the best trade he ever consummated in the whole course of his life.

During the next spring I bred largely again, and supplied all the best fanciers in New England and New York State with stock, from which they bred continually during that and the succeeding year.

In the spring of 1852 the Mutual Admiration Society of hen-men got up their third show, at the Fitchburg Dépôt (in May, I think), where a goodly exhibition came off, and where there were now fowls for sale of every conceivable color and description, good, bad, and indifferent. I contributed as usual, and, as usual, carried away the palm for the best samples shown. And here was evinced some of the shifts to which certain hucksters resorted, to make "the people" believe that white was black, that they originally brought this subject before the public eye, and that they only possessed the pure stock then in the country.

Reverends, and doctors, and deacons, and laymen, – all were there, in force. Every man cried down every other man's fowls, while he as strenuously cried up his own. Upon one cage appeared a card vouching for the fact that a certain original Shanghae crower within it, all the way from the land of the Celestials, weighed fourteen pounds and three ounces, and that a hen, with him, drew nine pounds six ounces (almost twenty-four pounds). When the birds were weighed, the first drew ten and a half pounds, and the other eight and a quarter only. This memorandum appeared upon the box of a clergyman contributor, who had understood that size and great weight only were to be the criterion of merit and value thenceforward. Another contributor boldly declared himself to be the original holder of the only good stock in America. A third claimed to be the father of the current movement, and had a gilded vane upon his boxes which he asserted he had had upon his poultry-house for five years previously. Another stated that all my fowls (there shown) were bred from his stock. And still another proclaimed that the identical birds which I contributed were purchased directly of him; he knew every one of them. Finally, one competitor impudently hinted that my birds actually then belonged to him, and had only been loaned to me (for a consideration) for exhibition on this occasion!