полная версия

полная версияThe History of the Hen Fever. A Humorous Record

Now, these prices may be looked upon by the uninitiated as extraordinary. So they were for this country. But at a Birmingham (Eng.) show, in the fall of 1852, a single pair of "Seabright Bantams," very small and finely plumed, sold for $125; a fine "Cochin-China" cock and two hens, for $75; and a brace of "White Dorkings," at $40. An English breeder went to London, from over a hundred miles distant, for the sole purpose of procuring a setting of Black Spanish eggs, and paid one dollar for each egg. Another farmer there sent a long distance for the best Cochin-China eggs, and paid one dollar and fifty cents each for them, at this time!

This was keeping up the rates with a vengeance, and beat us Yankees, out and out. But later accounts from across the water showed that this was only a beginning, even. In the winter of 1852 the Cottage Gardener stated that "within the last few weeks a gentleman near London sold a pair of Cochin-China fowls for 30 guineas ($150), and another pair for 32 guineas ($160). He has been offered £20 for a single hen; has sold numerous eggs at 1 guinea ($5) each, and has been paid down for chickens just hatched 12 guineas ($60) the half-dozen, to be delivered at a month old. One amateur alone had paid upwards of £100 for stock birds."

To this paragraph in the Gardener the Bury and Norwich Post added the following: "In our own neighborhood, during the past week, we happen to know that a cock and two hens (Cochin-Chinas) have been sold for 32 guineas, or $160. The fact is, choice birds, well bred, of good size and handsome plumage, are now bringing very high prices, everywhere; and the demand (in our own experience) has never been so great as at the present time."

In this way the fever raved and raged for a long year or more. Shows were being held all over this country, as well as in every principal city and town in England. Everybody bought fowls, and everybody had to pay for them, too, in 1852 and 1853!

In a notice of one of the English shows in that year (1853), a paper says: "There is a pen of three geese weighing forty-eight pounds; and among the Cochin-China birds are to be found hens which, in the period that forms the usual boundary of chicken life, have attained a weight of seven or eight pounds. Of the value of these birds it is difficult to speak without calling forth expressions of incredulity. It is evident that there is a desperate mania in bird-fancying, as in other things. Thus, for example, there is a single fowl to which is affixed the enormous money value of 30 guineas; two Cochin-China birds are estimated at 25 guineas; and four other birds, of the same breed, a cock and three hens, are rated in the aggregate at 60 guineas, – a price which the owner confidently expects them to realize at the auction-sale on Thursday. A further illustration of this ornithological enthusiasm is to be found in the fact that, at a sale on Wednesday last, one hundred and two lots, comprising one hundred and ten Cochin-China birds, all belonging to one lady, realized £369. 4s. 6d.; the highest price realized for a single one being 20 guineas."

Another British journal stated, a short time previously, that "a circumstance occurred which proves that the Cochin-China mania has by no means diminished in intensity. The last annual sale of the stock of Mr. Sturgeon, of Greys, has taken place at the Baker-street Bazaar. The two hundred birds there disposed of could not have realized a less sum than nearly £700 (or $3500), some of the single specimens being knocked down at more than £12, and very many producing £4, £5, and £6 each."

The attention, at this sale, devoted to the pedigree of the birds, was amusing to a mere observer; one fowl would be described as a cockerel by Patriarch, another as a pullet by Jerry, whilst a third was recommended as being the off-spring of Sam. Had the sale been one of horses, more care could hardly have been taken in describing their pedigrees or their qualifications. Many were praised by the auctioneer as being particularly clever birds, although in what their cleverness consisted did not appear. The fancy had evidently extended to all ranks in society. The peerage sent its representatives, who bought what they wanted, regardless of price. Nor was the lower house without its delegates; a well-known metropolitan ex-member seems to have changed his constituency of voters for one of Cochins; and we can only hope that it may not be his duty to hold an inquest on any that perish by a violent or unnatural death. The sums obtained for these birds depended on their being in strict accordance with the then taste of the fancy. They were magnificent in size, docile in behavior, intelligent in expression, and most of them were very finely bred.

And while the hen fever was thus at its height, almost, in England, we were following close upon the footsteps of John Bull in the United States. At the Boston Fowl Show in 1852, three Cochin-Chinas were sold at $100; a pair of Grey Chittagongs, at $50; two Canton Chinese fowls, at $80; three Grey Shanghae chicks, at $75; three White Shanghaes, at $65; six White Shanghae chickens, $40 to $45, etc.; and these prices, for similar samples, could have been obtained again and again.

At this time there was found an ambitious individual, occasionally, who got "ahead of his time," and whose laudable efforts to outstrip his neighbors were only checked by the natural results of his own superior "progressive" notions. A case in point:

"Way down in Lou'siana," for instance, a correspondent of mine stated that there lived one of these go-ahead fellows, who had been afflicted with a serious attack of hen fever, and who was not content with the ordinary speed and prolificness in breeding of the noted Shanghae fowls. He desired to possess himself of the biggest kind of a pile of chickens for the rapidly augmenting trade; and so he had constructed an Incubator, of moderate dimensions, into which he carefully stowed only three hundred nice fresh eggs, from his fancy fowls.

The secret of his plan to "astonish the boys" was limited to the knowledge of only two or three friends; and – thermometer in hand – he commenced operations. With close assiduity and Job-like patience, our amateur applied himself to his three weeks' task, by day and night, and at the end of fifteen days, one egg was broken, and Mr. Shanghae was thar, – alive and kicking, but as yet immature.

The neighborhood was in the greatest excitement at this prospect of success. Our friend commenced to crow (slightly), and, to hasten matters, put on, a leetle more steam at a venture. The twenty-second day arrived, and the "boys" assembled to witness the entrée of three hundred steam-hatched Shanghaes into this breathing world. Our amateur was full of expectation and "fever." One egg was broken; another, and then another; when, upon inspection, the entire mass was found to have been thoroughly boiled!

A desperate guffaw was heard as our amateur friend disappeared, and his only query since has been to ascertain what actual time is required to boil a certain quantity of eggs at a given heat, and the smallest probable cost thereof! As far as heard from, the reply has been, say six gallons of good alcohol, at one dollar per gallon, for three hundred eggs; time (night and day), twenty-two days and seven hours; and the product it is generally thought would make capital fodder for young turkeys, – provided said eggs are not boiled too hard!

On the subject of the diseases of poultry many learned and sapient dissertations appeared about these days. In one agricultural journal we remember to have met with the following scientific prescription. The learned writer is talking about roup in fowls, and says:

"This is probably a chronic condition, the result of frequent colds. Give the following medicines: Aconite, if there is fever, hepar-suliphuris third trituration, or mercury, third trituration, for a day or two, once in three or four hours; then pulsatilla tincture for the eyes; antimonium, third trituration or arsenic, or nux vomica, for the crop."

Isn't this clear, reader? How many poultry-raisers in the United States are there who would be likely to comprehend one line of this stuff? We advise this writer to try again; the above is an "elegant extract," verily!

We now come down to the fourth and last exhibition in Boston of the Mutual Admiration Society, alias the Association with the long-winded cognomen, which took place in September, 1852.

CHAPTER XVIII.

ONE OF THE FINAL KICKS

I was chosen by somebody (who will here permit me to present them my thanks for the honor) as one of the judges to decide upon the merits of the birds then to be exhibited: and my colleagues on this Committee were Dr. J.C. Bennett, and Messrs. Andrews, Balch and Fussell.

On the morning of the opening of this show the names of the judges were first announced to the contributors. Immediately there followed a "hullabaloo" that would have done credit to any bedlam, ancient or modern, ever heard or dreamed of. The lead in this burst of rebellion amongst the hitherto "faithful" was taken by one prominent member, who announced publicly, then and there, that the selection of the judges was an infamous imposition. They were incompetent, dishonest, prejudiced, calculating, speculative, ambitious competitors. Moreover, that it had all been "contrived by that damned Burnham, who would rob a church-yard, or steal the cents off the eyes of his dead uncle, any time, for the price of a hen."

These were the gentleman's own expressive words. He added that he could stand anything in the hen-trade but this. This, however, he would not submit to. Burnham should be kicked out of that Committee, or he would kick himself out of his boots, and the Society's traces also; – a threat which did not seem to alarm or disturb anybody, "as I knows on," except this same tall, stout, athletic, brave, honorable, honest, truthful, smart, gentlemanly member of this Mutual Admiration Society!

Now, it was very well known, at this time, that the Committee of Judges had been chosen entirely without their own knowledge. So far as I was myself concerned, I should greatly have preferred at that time to have remained an outsider, because it would have then been quite as well for me to have contributed to the exhibition, where, with the "splendid specimens" I then possessed of the Cochin-China and Shanghae varieties of fowl, I could have knocked all the others "higher than a fence" in that show, as I had done in all the previous exhibitions where I had ever competed with the boys.

But the same power which had formed the Committee of Judges also provided that they must not be competitors. Thus, three or four of those persons who had at the previous exhibitions of this Society been the most extensive contributors, – men who had bred by far the largest assortments and quantities of good fowls up to this period, and who had till now paid ten or twenty dollars for one (compared with any other of the members) toward the good of the association, and in the furtherance of its objects, —these men were made the judges, and were cut off as contributors. I was satisfied, however, because I saw that the framing of the Report of this show would fall to my lot again; and I had no doubt that, under these circumstances, I could afford to be "persecuted" for the time being.

It is not in my nature to harm anybody; and those who are personally acquainted with me, know that I am constitutionally of a calm, retiring, meek, religious turn of mind. My aim in life is to "do unto others as I would have others do unto me." I "love my neighbor" (if he doesn't permit his hens to get into my garden) "as myself." And, "if a man smite me upon one cheek, I turn to him the other also," immediately, if not sooner. I never retaliate upon an enemy or an opponent – until I make sure that I have him where the hair is short.

I once knew of an extraordinary instance of patience that taught me a powerful lesson in submissiveness. It occurred in a Western court, where the judge (a most exemplary man, I remember) sat for two mortal days quietly listening to the arguments of a couple of contending lawyers in reference to the construction they desired him to assume in regard to a certain act of the Legislature of that State. When the two legal gentlemen had "thrown themselves," in this long and wearying debate, for forty-eight hours, his Honor cut off the controversy by remarking, very quietly,

"Gentlemen, this law that you have been speaking of has been repealed!"

I thought of this circumstance, and I permitted the hen-men to gas, to their hearts' content. When they got through with their anathemas, their spleen, and their stupidity, I informed them that the "Committee" had unanimously left to my charge the writing of the Report of that Exhibition.

From that moment, up to the hour when the Report was published, I never suspected (before) that I had so many friends in this world!

The fear that seemed to pervade every mind present was, that I should probably do precisely what they would have done under similar circumstances, – to wit, take care of myself.

I had no fowls in this exhibition; but there were present numerous specimens bred from my stock, that were very choice (so every one said), and which commanded the highest prices during the show.

There were several Southern gentlemen present, who bought (and paid roundly for them, too) some of the best fancy-birds on sale. It was astonishing how much some of those buyers did know about the different breeds of Chinese fowls there! Yes, it certainly was astounding! I think I never saw before so much real, downright bona fide knowledge of henology displayed as was shown by one or two Southern gentlemen, then and there; – never, in the whole course of my experience!

By reference to the next chapter, it will be seen how shamefully I neglected my own interests, and how self-sacrificing I was in the report of the Society's last kick, which, as I have already hinted, the Committee left to my charge to prepare.

I had no disposition (in the preparation of this document) to underrate the stock of any one else, provided it did not interfere with me! And, after carefully noting down whatever seemed of importance to my well-being there, I sat myself down to oblige the Committee by writing the "Report" of this show, which an ill-natured competitor subsequently declared was "only in favor of Burnham and his stock, all over, underneath, in the middle, outside, overhead, on top, on all sides, and at both ends!"

And I believe he was right!

CHAPTER XIX.

THE FOURTH FOWL-SHOW IN BOSTON

This show (in September, 1852) was the fifth exhibition held in Boston, but the fourth only of the Society with the long name.

The Report commences with a congratulation (as usual) that the association still lives, and has a being; and, after alluding to the general state of the affairs of the concern, – without touching upon its financial condition, – it thus proceeds:

"Your Committee would call your attention to the fact that among the numerous fowls exhibited this season, – as upon former occasions, – a very unnecessary practice seems to have obtained, in the mis-naming of varieties. Crossbred fowls have been called by original cognomens, unknown to practical breeders; and a host of birds well known to the Committee, as well as to poulterers generally, have been denominated by any other than their real and universally conceded ornithological titles. This savors of bad taste; it leads to ridicule among strangers who visit our shows from abroad; and should not be sanctioned by your Society. Errors may creep in among your transactions, in this particular, and many honest, careful breeders may be deceived; but the multiplying of unpronounceable and meaningless names for domestic fowls is entirely uncalled for; and your committee recommend a close adherence, hereafter, to recognized titles only.

"In this connection, it may be proper to allude to a case in point. The largest and unquestionably one of the finest varieties of domestic fowls ever shown among us was entered by the breeders of this variety as the 'Chittagong;' other coops of the same stock were labelled 'Grey Chittagongs;' others were called 'Bramah Pootras;' and others, 'Grey Shanghae' and 'Malays.'

"Your Committee are divided in opinion as to what these birds ought, rightfully, to be called, – though the majority of the Committee have no idea that 'Bramah Pootra' is their correct title. That they are not 'Malays' is also quite as clear. Several of the specimens are positively known to have come direct from Shanghae; and none are known to have come originally from anywhere else. Nevertheless, it has been thought proper to leave this question open, for the present; and the Committee, believing that this fowl originates in and hails directly from the East, are content to accept for them the title of 'Grey Shanghae,' 'Chittagong,' or 'Bramah Pootra,' as different breeders may elect, – admitting, at the same time, that they are really a very superior bird, and believing that if carefully bred they may be found decidedly the most valuable among all the large Chinese breeds, of which they are clearly a good variety."

"A large sum of money was expended at this exhibition, by visitors, amateurs and breeders, – one gentleman investing upwards of $700 in choice fowls; another, from the South, purchasing to the amount of $350 for extra samples; another bought $200 worth, etc. The highest figures ever yet paid on this side of the Atlantic (for individual purchases) were realized at this show.

"Samples of the China stock originally imported from Shanghae were very plentiful on this occasion, and the high reputation of this blood was fully sustained in the specimens exhibited. Very superior fowls, bred from G.P. Burnham's importations of Cochin-Chinas, were also numerous, and were sold, in four or five instances, at the very highest prices paid for any samples that were disposed of."

Among the premiums awarded to the Chinese fowls by this "Committee," were the following:

"China Fowls. – To H.H. Williams, best cock and two hens (of Burnham's Canton importation), $5. To C. Sampson, West Roxbury, best cock and single hen (Burnham's Canton importation), $3. To H.H. Williams, third prize, for same stock, $2. To C.C. Plaisted, Great Falls, N.H., the Committee awarded a first prize, $5, for what he called 'Hong-Kong' fowls; these were of Burnham's Canton stock, also. To A. White, E. Randolph, for six best chickens (Burnham's importation), $2.

"Cochin-China. – To H.H. Williams, West Roxbury, best cock and two hens (splendid samples, of extraordinary size and beauty), first prize, $5. To A. White, E. Randolph, best cock and single hen (of Burnham's importation), $3. To A. White, for six best chickens (Burnham's importation), $2."

The Committee then allude to the prices which were paid there for fowls, "not because they advocate the propriety of keeping them up" (O, no!), "but rather to show that the welfare of the Association is by no means derogating.

"The three prize Cochin-China fowls were sold for $100. The two prize Grey Shanghaes, or 'Bramah Pootras,' were sold for $50. Three chickens of the same, at $50. A pair of Burnham's importation of Cochins, at $80; another pair, at $40; another trio (chickens), at $40. Six Black Spanish chickens (Child's), at $50. Six White Shanghae chickens (Wight's), at $45. Three hens, of same stock, at $50 – and several pairs and trios of other varieties, at from $25 each, to $25 and $30 to $40 the lot."

At a subsequent meeting of the Trustees, Mr. George P. Burnham, on the part of the Judges at the late exhibition of the Society, presented their Report, whereupon it was

"Voted, That the Report of the Judges on the recent show of poultry in the Public Garden be accepted."

And this was the end of that ball of worsted! I rather have the impression, now, – as nearly as I can recollect (though my memory is somewhat treacherous in these matters), but I think I sold a few fowls, just after that fair. "I may be mistaken, – but that is my opinion!"

The Report was duly accepted, in form, and I had the satisfaction of seeing my "extraordinary" and "superb" stock again lauded to the very echo, at the expense of the old-fogyism of the "Mutual Admiration Society."

The consequence was a renewed activity in my sales, which continued delightfully lively and correspondingly remunerative for several months after this exhibition, also, where I did not enter the first fowl!

CHAPTER XX.

PRESENT TO QUEEN VICTORIA

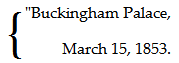

I have already alluded to the fine Grey Shanghaes which I forwarded to Her Majesty the Queen. In relation to this circumstance the Boston papers contained the following announcement, in the month of April, 1853; a circumstance which did not greatly retard the prospects of my business either on this or on the other side of the water! The compliment thus paid me by Royalty was duly appreciated, and its delicacy will be apparent to the reader. This picture is the only one of its kind ever sent to an American citizen.

"A Compliment from Victoria. – Some weeks ago, Mr. George P. Burnham, of Boston, forwarded to Her Majesty Queen Victoria a present of some Grey Shanghae fowls, which have been greatly admired in England. By the last steamer Mr. Burnham received the following letter from Her Majesty's Secretary of the Privy Purse, accompanying a fine portrait of the Queen, sent over to Mr. B.:

The Queen's Letter

"Dear Sir: I have received the commands of Her Majesty the Queen, to assure you of Her Majesty's high appreciation for the kind motives which prompted you to forward for her acceptance the magnificent 'Grey Shanghae' fowls which have been so much admired at Her Majesty's aviary at Windsor.

"Her Majesty has accepted, with great pleasure, such a mark of respect and regard, from a citizen of the United States.

"I have, by Her Majesty's command, shipped in the 'George Carl,' to your address, a case containing a portrait of Her Majesty, of which the Queen has directed me to request your acceptance.

"I have the honor to be,

"Sir, your ob't and humble servant,"C.B. Phipps."To Geo. P. Burnham, Esq.,

Boston, U.S.A."

I caused a copy to be taken from this portrait of the Queen, and have had it engraved for this book; it appears as the frontispiece.

Immediately after this paragraph appeared, a new zest appeared to have been given to the Grey Shanghae trade. Orders came from Canada and from Nova Scotia to a very considerable amount; and during this season my sales were again very large. During the year 1853, I started and raised over sixteen hundred chickens of all kinds; but this did not supply my orders. I bought largely, and paid high prices, too, generally. But few persons were now doing any business in the fowl-trade, except myself, however.

The N.Y. Spirit of the Times published portraits of the birds sent to the Queen, and remarked that "the engraving represented six of the nine beautiful Grey Shanghae fowls lately presented to Her Majesty Victoria, Queen of Great Britain, by George P. Burnham, Esq., of Boston, Mass.

"These birds were forwarded by one of the last month's Collins steamers, in charge of Adams & Co.'s Express, and passed through this city on the 24th ult. Their extraordinary size and fine plumage were the admiration of all who examined them. The picture is from life, engraved by Brown, and is a faithful representation of the birds, which are very closely bred.

"The color of this variety of the China fowl is a light silver-grey, approximating to white; the body is a light downy white, sparsely spotted and pencilled with metallic black in the tail and wing tips; the legs are feathered to the toes, and the form is unexceptionable for a large fowl; this variety having proved the biggest of all the 'Shanghaes' yet imported into this State.