полная версия

полная версияThe Life of Albert Gallatin

BOOK III.

THE TREASURY. 1801-1813

IN governments, as in households, he who holds the purse holds the power. The Treasury is the natural point of control to be occupied by any statesman who aims at organization or reform, and conversely no organization or reform is likely to succeed that does not begin with and is not guided by the Treasury. The highest type of practical statesmanship must always take this direction. Washington and Jefferson doubtless stand pre-eminent as the representatives of what is best in our national character or its aspirations, but Washington depended mainly upon Hamilton, and without Gallatin Mr. Jefferson would have been helpless. The mere financial duties of the Treasury, serious as they are, were the least of the burdens these men had to carry; their keenest anxieties were not connected most nearly with their own department, but resulted from that effort to control the whole machinery and policy of government which is necessarily forced upon the holder of the purse. Possibly it may be said with truth that a majority of financial ministers have not so understood their duties, but, on the other hand, the ministers who composed this majority have hardly left great reputations behind them. Perhaps, too, the very magnitude and overshadowing influence of the Treasury have tended to rouse a certain jealousy in the minds of successive Presidents, and have worked to dwarf an authority legitimate in itself, but certainly dangerous to the Executive head. Be this as it may, there are, to the present time, in all American history only two examples of practical statesmanship which can serve as perfect models, not perhaps in all respects for imitation, but for study, to persons who wish to understand what practical statesmanship has been under an American system. Public men in considerable numbers and of high merit have run their careers in national politics, but only two have had at once the breadth of mind to grapple with the machine of government as a whole, and the authority necessary to make it work efficiently for a given object; the practical knowledge of affairs and of politics that enabled them to foresee every movement; the long apprenticeship which had allowed them to educate and discipline their parties; and finally, the good fortune to enjoy power when government was still plastic and capable of receiving a new impulse. The conditions of the highest practical statesmanship require that its models should be financiers; the conditions of our history have hitherto limited their appearance and activity to its earlier days.

The vigor and capacity of Hamilton’s mind are seen at their best not in his organization of the Treasury Department, which was a task within the powers of a moderate intellect, nor yet in the essays which, under the name of reports, instilled much sound knowledge, besides some that was not so sound, into the minds of legislature and people; still less are they shown in the arts of political management, – a field into which his admirers can follow him only with regret and some sense of shame. The true ground of Hamilton’s great reputation is to be found in the mass and variety of legislation and organization which characterized the first Administration of Washington, and which were permeated and controlled by Hamilton’s spirit. That this work was not wholly his own is of small consequence. Whoever did it was acting under his leadership, was guided consciously or unconsciously by his influence, was inspired by the activity which centred in his department, and sooner or later the work was subject to his approval. The results – legislative and administrative – were stupendous and can never be repeated. A government is organized once for all, and until that of the United States fairly goes to pieces no man can do more than alter or improve the work accomplished by Hamilton and his party.

What Hamilton was to Washington, Gallatin was to Jefferson, with only such difference as circumstances required. It is true that the powerful influence of Mr. Madison entered largely into the plan of Jefferson’s Administration, uniting and modifying its other elements, and that this was an influence the want of which was painfully felt by Washington and caused his most serious difficulties; it is true, too, that Mr. Jefferson reserved to himself a far more active initiative than had been in Washington’s character, and that Mr. Gallatin asserted his own individuality much less conspicuously than was done by Mr. Hamilton; but the parallel is nevertheless sufficiently exact to convey a true idea of Mr. Gallatin’s position. The government was in fact a triumvirate almost as clearly defined as any triumvirate of Rome. During eight years the country was governed by these three men, – Jefferson, Madison, and Gallatin, – among whom Gallatin not only represented the whole political influence of the great Middle States, not only held and effectively wielded the power of the purse, but also was avowedly charged with the task of carrying into effect the main principles on which the party had sought and attained power.

In so far as Mr. Jefferson’s Administration was a mere protest against the conduct of his predecessor, the object desired was attained by the election itself. In so far as it represented a change of system, its positive characteristics were financial. The philanthropic or humanitarian doctrines which had been the theme of Mr. Jefferson’s philosophy, and which, in a somewhat more tangible form, had been put into shape by Mr. Gallatin in his great speech on foreign intercourse and in his other writings, when reduced to their simplest elements amount merely to this: that America, standing outside the political movement of Europe, could afford to follow a political development of her own; that she might safely disregard remote dangers; that her armaments might be reduced to a point little above mere police necessities; that she might rely on natural self-interest for her foreign commerce; that she might depend on average common sense for her internal prosperity and order; and that her capital was safest in the hands of her own citizens. To establish these doctrines beyond the chance of overthrow was to make democratic government a success, while to defer the establishment of these doctrines was to incur the risk, if not the certainty, of following the career of England in “debt, corruption, and rottenness.”

In this political scheme, whatever its merits or its originality, everything was made to depend upon financial management, and, since the temptation to borrow money was the great danger, payment of the debt was the great dogma of the Democratic principle. “The discharge of the debt is vital to the destinies of our government,” wrote Mr. Jefferson to Mr. Gallatin in October, 1809, when the latter was desperately struggling to maintain his grasp on the Administration; “we shall never see another President and Secretary of the Treasury making all other objects subordinate to this.” And Mr. Gallatin replied: “The reduction of the debt was certainly the principal object in bringing me into office.” With the reduction of debt, by parity of reasoning, reduction of taxation went hand in hand. On this subject Mr. Gallatin’s own words at the outset of his term of office give the clearest idea of his views. On the 16th November, 1801, he wrote to Mr. Jefferson:

“If we cannot, with the probable amount of impost and sale of lands, pay the debt at the rate proposed and support the establishments on the proposed plans, one of three things must be done; either to continue the internal taxes, or to reduce the expenditure still more, or to discharge the debt with less rapidity. The last recourse to me is the most objectionable, not only because I am firmly of opinion that if the present Administration and Congress do not take the most effective measures for that object, the debt will be entailed on us and the ensuing generations, together with all the systems which support it and which it supports, but also, any sinking fund operating in an increased ratio as it progresses, a very small deduction from an appropriation for that object would make a considerable difference in the ultimate term of redemption which, provided we can in some shape manage the three per cents, without redeeming them at their nominal value, I think may be paid at fourteen or fifteen years.

“On the other hand, if this Administration shall not reduce taxes, they never will be permanently reduced. To strike at the root of the evil and avert the danger of increasing taxes, encroaching government, temptations to offensive wars, &c., nothing can be more effectual than a repeal of all internal taxes; but let them all go and not one remain on which sister taxes may be hereafter engrafted. I agree most fully with you that pretended tax-preparations, treasure-preparations, and army-preparations against contingent wars tend only to encourage wars. If the United States shall unavoidably be drawn into a war, the people will submit to any necessary tax, and the system of internal taxation which then shall be thought best adapted to the then situation of the country may be created instead of engrafted on the old or present plan. If there shall be no real necessity for them, their abolition by this Administration will most powerfully deter any other from reviving them.”

To these purposes, in the words of Mr. Jefferson, all other objects were made subordinate, and to carry these purposes into effect was the peculiar task of Mr. Gallatin. No one else appears even to have been thought of; no one else possessed any of the requisites for the place in such a degree as made him even a possible rival. The whole political situation dictated the selection of Mr. Gallatin for the Treasury as distinctly as it did that of Mr. Jefferson for the Presidency.

But the condition on which alone the principles of the Republicans could be carried out was that of peace. To use again Mr. Gallatin’s own words, written in 1835: “No nation can, any more than any individual, pay its debts unless its annual receipts exceed its expenditures, and the two necessary ingredients for that purpose, which are common to all nations, are frugality and peace. The United States have enjoyed the last blessing in a far greater degree than any of the great European powers. And they have had another peculiar advantage, that of an unexampled increase of population and corresponding wealth. We are indebted almost exclusively for both to our geographical and internal situation, the only share which any Administration or individual can claim being its efforts to preserve peace and to check expenses either improper in themselves or of subordinate importance to the payment of the public debt. In that respect I may be entitled to some public credit, as nearly the whole of my public life, from 1795, when I took my seat in Congress, till 1812, when the war took place, was almost exclusively devoted with entire singleness of purpose to those objects.”50

To preserve peace, therefore, in order that the beneficent influence of an enlightened internal policy might have free course, was the special task of Mr. Madison. How much Mr. Gallatin’s active counsel and assistance had to do with the foreign policy of the government will be seen in the narrative. Here, however, lay the danger, and here came the ultimate shipwreck. It is obvious at the outset that the weak point of what may be called the Jeffersonian system lay in its rigidity of rule. That system was, it must be confessed, a system of doctrinaires, and had the virtues and faults of a priori reasoning. Far in advance, as it was, of any other political effort of its time, and representing, as it doubtless did, all that was most philanthropic and all that most boldly appealed to the best instincts of mankind, it made too little allowance for human passions and vices; it relied too absolutely on the power of interest and reason as opposed to prejudice and habit; it proclaimed too openly to the world that the sword was not one of its arguments, and that peace was essential to its existence. When narrowed down to a precise issue, and after eliminating from the problem the mere dogmas of the extreme Hamiltonian Federalists, the real difference between Mr. Jefferson and moderate Federalists like Rufus King, who represented four-fifths of the Federal party, lay in the question how far a government could safely disregard the use of force as an element in politics. Mr. Jefferson and Mr. Gallatin maintained that every interest should be subordinated to the necessity of fixing beyond peradventure the cardinal principles of true republican government in the public mind, and that after this was accomplished, a result to be marked by extinction of the debt, the task of government would be changed and a new class of duties would arise. Mr. King maintained that republican principles would take care of themselves, and that the government could only escape war and ruin by holding ever the drawn sword in its hand. Mr. Gallatin, his eyes fixed on the country of his adoption, and loathing the violence, the extravagance, and the corruption of Europe, clung with what in a less calm mind would seem passionate vehemence to the ideal he had formed of a great and pure society in the New World, which was to offer to the human race the first example of man in his best condition, free from all the evils which infected Europe, and intent only on his own improvement. To realize this ideal might well, even to men of a coarser fibre than Mr. Gallatin, compensate for many insults and much wrong, borne with dignity and calm remonstrance. True, Mr. Gallatin always looked forward to the time when the American people might safely increase its armaments; but he well knew that, as the time approached, the need would in all probability diminish: meanwhile, he would gladly have turned his back on all the politics of Europe, and have found compensation for foreign outrage in domestic prosperity. The interests of the United States were too serious to be put to the hazard of war; government must be ruled by principles; to which the Federalists answered that government must be ruled by circumstances.

The moment when Mr. Jefferson assumed power was peculiarly favorable for the trial of his experiment. Whatever the original faults and vices of his party might have been, ten years of incessant schooling and education had corrected many of its failings and supplied most of its deficiencies. It was thoroughly trained, obedient, and settled in its party doctrines. And while the new administration thus profited by the experience of its adversity, it was still more happy in the inheritance it received from its predecessor. Whatever faults the Federalists may have committed, and no one now disputes that their faults and blunders were many, they had at least the merit of success; their processes may have been clumsy, their tempers were under decidedly too little control, and their philosophy of government was both defective and inconsistent; but it is an indisputable fact, for which they have a right to receive full credit, that when they surrendered the government to Mr. Jefferson in March, 1801, they surrendered it in excellent condition. The ground was clear for Mr. Jefferson to build upon. Friendly relations had been restored with France without offending England; for the first time since the government existed there was not a serious difficulty in all our foreign relations, the chronic question of impressment alone excepted; the army and navy were already reduced to the lowest possible point; the civil service had never been increased beyond very humble proportions; the debt, it is true, had been somewhat increased, but in nothing like proportion to the increase of population and wealth; and through all their troubles the Federalists had so carefully managed taxation that there was absolutely nothing for Mr. Gallatin to do, and he attempted nothing, in regard to the tariff of impost duties, which were uniformly moderate and unexceptionable, while even in regard to the excise and other internal taxes he hesitated to interfere. This almost entire absence of grievances to correct extended even to purely political legislation. The alien and sedition laws expired by limitation before the accession of Mr. Jefferson, and only the new organization of the judiciary offered material for legislative attack. Add to all this that Europe was again about to recover peace.

On the other hand, the difficulties with which Mr. Jefferson had to deal were no greater than always must exist under any condition of party politics. From the Federalists he had nothing to fear; they were divided and helpless. The prejudices and discords of his own followers were his only real danger, and principally the pressure for office which threatened to blind the party to the higher importance of its principles. In proportion as he could maintain some efficient barrier against this and similar excesses and fix the attention of his followers on points of high policy, his Administration could rise to the level of purity which was undoubtedly his ideal. What influence was exerted by Mr. Gallatin in this respect will be shown in the course of the narrative.

The assertion that Jefferson, Madison, and Gallatin were a triumvirate which governed the country during eight years takes no account of the other members of Mr. Jefferson’s Cabinet, but in point of fact the other members added little to its strength. The War Department was given to General Dearborn, while Levi Lincoln became Attorney-General; both were from Massachusetts, men of good character and fair though not pre-eminent abilities. Mr. Gallatin described them very correctly in a letter written at the time:

GALLATIN TO MARIA NICHOLSONCity of Washington, 12th March, 1801.My dear Sister, – I think I am going to reform; for I feel a kind of shame at having left your friendly letters so long unanswered. How it happens that I often have and still now do apparently neglect, at least in the epistolary way, those persons who are dearest to me, must be unaccountable to you. I think it is owing to an indulgence of indolent habits and to want of regularity in the distribution of my time. In both a thorough reformation has become necessary, and as that necessity is the result of new and arduous duties, I do not know myself, or I will succeed in accomplishing it. You will easily understand that I allude to the office to which I am to be appointed. This has been decided for some time, and has been the cause of my remaining here a few days longer than I expected or wished. To-morrow morning I leave this place, and expect to return about the first day of May with my wife and family. Poor Hannah has been and is so forlorn during my absence, and she meets with so many difficulties in that western country, for which she is not fit and which is not fit for her, that I will at least feel no reluctance in leaving it. Yet were my wishes alone to be consulted I would have preferred my former plan with all its difficulties, that of studying law and removing to New York. As a political situation the place of Secretary of the Treasury is doubtless more eligible and congenial to my habits, but it is more laborious and responsible than any other, and the same industry which will be necessary to fulfil its duties, applied to another object, would at the end of two years have left me in the possession of a profession which I might have exercised either in Philadelphia or New York. But our plans are all liable to uncertainty, and I must now cheerfully undertake that which had never been the object of my ambition or wishes, though Hannah had always said that it should be offered to me in case of a change of Administration.

… As to our new Administration, the appearances are favorable, but storms must be expected. The party out of power had it so long, loved it so well, struggled so hard to the very last to preserve it, that it cannot be expected that the leaders will rest contented after their defeat. They mean to rally and to improve every opportunity which our errors, our faults, or events not under our control may afford them. As to ourselves, Mr. Jefferson’s and Mr. Madison’s characters are well known to you. General Dearborn is a man of strong sense, great practical information on all the subjects connected with his Department, and what is called a man of business. He is not, I believe, a scholar, but I think he will make the best Secretary of War we [have] as yet had. Mr. Lincoln is a good lawyer, a fine scholar, a man of great discretion and sound judgment, and of the mildest and most amiable manners. He has never, I should think from his manners, been out of his own State or mixed much with the world except on business. Both are men of 1776, sound and decided Republicans; both are men of the strictest integrity; and both, but Mr. L. principally, have a great weight of character to the Eastward with both parties. We have as yet no Secretary of the Navy, nor do I know on whom the choice of the President may fall, if S. Smith shall persist in refusing…

The Navy Department in a manner went begging. General Smith was strongly pressed to take it, and did in fact perform its duties for several weeks. Had he consented to accept the post he would have added to the weight of the government, for General Smith was a man of force and ability; but he persisted in refusing, and ultimately his brother, Robert Smith, was appointed, an amiable and respectable person, but not one of much weight except through his connections by blood or marriage.

The first act of the new Cabinet was to reach a general understanding in regard to the objects of the Administration. These appear to have been two only in number: reduction of debt and reduction of taxes, and the relation to be preserved between them. On the 14th March, Mr. Gallatin wrote a letter to Mr. Jefferson, discussing the subject at some length;51 immediately afterwards he set out for New Geneva to arrange his affairs there and to bring his wife and family to Washington. His sharp experience of repeated exclusion from office by legislative bodies made him nervous in regard to confirmation by the Senate, and Mr. Jefferson therefore postponed the appointment until after the Senate had adjourned. These fears of factious opposition were natural enough, but seem to have been unfounded. Samuel Dexter, the Secretary of the Treasury under President Adams, consented to hold over until Mr. Gallatin was ready. Mr. Stoddart, President Adams’s Secretary of the Navy, was equally courteous. If the story, told in some of Mr. Jefferson’s biographies, be true, that Mr. Marshall, while still acting as Secretary of State, was turned out of his office by Mr. Lincoln, under the orders of Mr. Jefferson, at midnight on the 3d of March,52 it must be confessed that, so far as courtesy was concerned, the Federalists were decidedly better bred than their rivals. The new Administration was in no way hampered or impeded by the old one, and Mr. Gallatin himself was perhaps of the whole Administration the one who suffered least from Federal attacks; henceforward his enemies came principally from his own camp. This result was natural and inevitable; it came from his own character, and was a simple consequence of his principles; but, since this internal dissension forced itself at once on the Administration and became to some extent its crucial test in the matter of removals from office for party reasons, the whole story may best be told here before proceeding with the higher subjects of state policy.

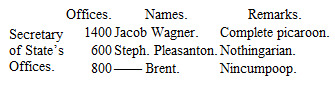

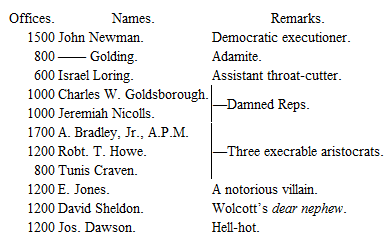

Among Mr. Gallatin’s papers is a sort of pamphlet in manuscript, stitched together, and headed in ornamental letters: “Citizen W. DUANE.” It is endorsed in Mr. Gallatin’s hand: “1801. Clerks in offices; given by W. Duane.” It contains a list of all the Department clerks, after the following style:

Some of Duane’s remarks are still more pointed:

The pressure for sweeping removals was very great. From the first, Mr. Gallatin set his face against them, and although apparently yielding adhesion to Mr. Jefferson’s famous New Haven letter of July 12, in which it was attempted to justify the principle and regulate the proportion of removals, he urged Mr. Jefferson to authorize the issue of a circular to collectors which would have practically made the New Haven letter a nullity. On the 25th July he sent to the President a draft of this circular: