полная версия

полная версияThe Life of Albert Gallatin

The summer and autumn of 1801 were consumed in mastering the details of Treasury business, in filling appointments to office, and in settling the scale of future expenditure in the different Departments. But when the time came for the preparation of the President’s message at the meeting of Congress in December, Mr. Gallatin had not yet succeeded in reaching a decision on the questions of the internal revenue and of the debt. He had the support of the Cabinet on the main point, that payment of the debt should take precedence of reduction in the taxes, but reduction in the taxes was dependent on the amount of economy that could be effected in the navy, and the Secretary of the Navy resisted with considerable tenacity the disposition to reduce expenditures.

What Mr. Gallatin would have done with the navy, had he been left to deal with it in his own way, nowhere appears. He had opposed its construction, and would not have considered it a misfortune if Congress had swept it away; but he seems never to have interfered with it, after coming into office, further than to insist that the amount required for its support should be fixed at the lowest sum deemed proper by the head of that Department. In fact, Mr. Jefferson’s Administration disappointed both friends and enemies in its management of the navy. The furious outcry which the Federalists raised against it on that account was quite unjust. Considering the persistent opposition which the Republican party had offered to the construction of the frigates, there can be no better example of the real conservatism of this Administration than the care which it took of the service, and even Mr. Gallatin, who honestly believed that the money would be better employed in reducing debt, grumbled not so much at the amount of the appropriations as at the want of good management in its expenditure. He thought that more should have been got for the money; but so far as the force was concerned, the last Administration had itself fixed the amount of reduction, and the new one only acted under that law, using the discretion given by it. That this is not a mere partisan apology is proved by the effective condition of our little navy in 1812; but the facts in regard to the subject are well known and fully stated in the histories of that branch of the service, – works in which there was no motive for political misrepresentation.54

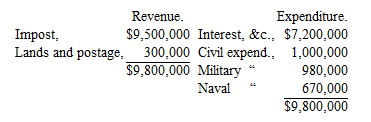

Mr. Jefferson was in the habit of communicating the draft of his annual message to each head of department and requesting them to furnish him with their comments in writing. On these occasions Mr. Gallatin’s notes were always elaborate and interesting. In his remarks in November, 1801, on the first annual message he gave a rough sketch of the financial situation, and at this time it appears that he hoped to cut down the army and navy estimates to $930,000 and $670,000 respectively. His financial scheme then stood as follows:

He calculated that the annual application of $7,200,000 to the payment of interest and principal would pay off about thirty-eight millions of the debt in eight years, and, fixing this as his standard, he proposed to make the other departments content themselves with whatever they could get as the difference between $7,200,000 and the revenue estimated at $9,800,000. On these terms alone he would consent to part with the internal revenue, which produced about $650,000.

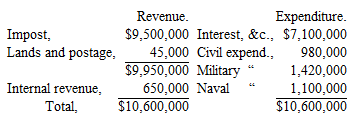

This, however, seems to have been beyond his power. Few finance ministers have ever pressed their economies with more perseverance or authority than Mr. Gallatin, but he never succeeded in carrying on the government with so much frugality as this, and the sketch seems to indicate what the Administration would have liked to do, rather than what it did. The report of the Secretary of the Treasury a month later shows that he had been obliged to modify his plan. As officially announced, it was as follows:

The problem of repealing the internal taxes was therefore not yet settled, and it is not very clear on the face of the estimates how it would be possible to effect this object. Mr. Gallatin expected to do it by economies in the military and naval establishments by which he should save the necessary $650,000. It is worth while to look forward over his administration and to see how far this expectation was justified, in order to understand precisely what his methods were.

His first step, as already noticed, was to fix the rate at which the debt should be discharged. This rate was ultimately represented by an annual appropriation of $7,300,000, which at the end of eight years, according to his first report, would pay off $32,289,000, and leave $45,592,000 of the national debt, and within the year 1817 would extinguish that debt entirely. This sum of $7,300,000 was therefore to be set aside out of the revenue as the permanent provision for paying the principal and interest of the debt.

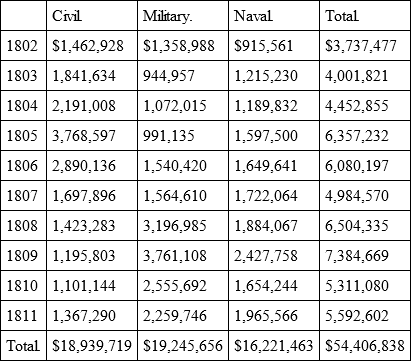

Of the residue of income, which, without the internal taxes, was estimated at about $2,700,000, the civil expenditure was to require one million, the army and navy the remainder. But the tables of actual expenditure show a very different result:

From these figures it appears that Mr. Gallatin’s proposed economies were never realized, and that his results must have been attained by other means. The average expenditure on the navy during these ten years was $1,600,000 a year. Instead of establishments costing $2,700,000, the average annual expenditure reached $5,400,000, or precisely double the amount named. As a matter of fact, notwithstanding the frugality of Mr. Gallatin and the complaints of parsimony made by the Federalists, it is difficult to see how Mr. Jefferson’s Administration was in essentials more economical than its predecessors, and this seems to have been Mr. Gallatin’s own opinion at least so far as concerned the Navy Department. On the 18th January, 1803, he wrote a long letter to Mr. Jefferson on the navy estimates, closing with a strong remonstrance: “I cannot discover any approach towards reform in that department, and I hope that you will pardon my stating my opinion on that subject when you recollect with what zeal and perseverance I opposed for a number of years, whilst in Congress, similar loose demands for money. My opinions on that subject have been confirmed since you have called me in the Administration, and although I am sensible that in the opinion of many wise and good men my ideas of expenditure are considered as too contracted, I feel a strong confidence that on this particular point I am right.” Again, on the 20th May, 1805, he renewed his complaint: “It is proper that I should state that the War Department has assisted us in that respect [economy] much better than the Navy Department… As I know that there was an equal wish in both departments to aid in this juncture, it must be concluded either that the War is better organized than the Navy Department, or that naval business cannot be conducted on reasonable terms. Whatever the cause may be, I dare predict that whilst that state of things continues we will have no navy nor shall progress towards having one. As a citizen of the United States it is an event that I will not deprecate, but I think it due to the credit of your Administration that, after so much has been expended on that account, you should leave an increase of, rather than an impaired fleet. On this subject, the expense of the navy greater than the object seemed to require, and a merely nominal accountability, I have, for the sake of preserving perfect harmony in your councils, however grating to my feelings, been almost uniformly silent, and I beg that you will ascribe what I now say to a sense of duty and to the grateful attachment I feel for you.”

Nevertheless, the internal duties were abolished as one of the first acts of Mr. Jefferson’s Administration, and at the same time Congress adopted Mr. Gallatin’s scheme of regulating the discharge of the public debt. The truth appears to be that the repeal of these taxes was a party necessity, and that under the pressure of that necessity both the Secretary of War and the Secretary of the Navy were induced to lower their estimates to a point at which Mr. Gallatin would consent to part with the tax. Mr. Gallatin never did officially recommend the repeal. This measure was founded on a report of John Randolph for the Committee of Ways and Means, and Mr. Randolph’s recommendation rested on letters of the War and Navy Secretaries promising an economy of $600,000 in their combined departments. These economies never could be effected. The resource which for the time carried Mr. Gallatin successfully over his difficulties was simply the fact that he had taken the precaution to estimate the revenue very low, and that there was uniformly a considerable excess in the receipts over the previous estimate; but even this good fortune was not enough to save Mr. Gallatin’s plan from failure. The war with Tripoli had already begun, and further economies in the navy were out of the question. Government attempted for two years to persevere in its scheme, but it soon became evident that, even with the increased production of the import duties, the expense of that war could not be met without recovering the income sacrificed by the repeal of the internal taxes in 1802. Accordingly an addition of 2½ per cent, was imposed on all imported articles which paid duty ad valorem. The result of the whole transaction, therefore, amounted only to a shifting of the mode of collection, or, in other words, instead of raising a million dollars from whiskey, stamps, &c., the million was raised on articles of foreign produce or manufacture. This extra tax was called the Mediterranean Fund, and was supposed to be a temporary resource for the Tripolitan war.

The final adjustment of this difficulty, therefore, took a simple shape. Mr. Gallatin obtained his fund of $7,300,000 for discharging principal and interest of the debt. This was what he afterwards called his “fundamental substantial measure,” which was intended to affirm and fix upon the government the principle of paying its debt and of thus separating itself at once from the whole class of corruptions and political theories which were considered as the accompaniment of debt and which were at that time identified with English and monarchical principles. To obtain the surplus necessary for maintaining this fund he relied at first on frugality, and, finding that circumstances offered too great a resistance in this direction, he resorted to taxation in the most economical form he could devise. In regard to mere machinery he made every effort to simplify rather than to complicate it. In his own words: “As to the forms adopted for attaining that object [payment of the debt], they are of a quite subordinate importance. Mr. Hamilton adopted those which had been introduced in England by Mr. Pitt, the apparatus of commissioners of the sinking fund, in whom were vested the redeemed portions of the debt, which I considered as entirely useless, but could not as Secretary of the Treasury attack in front, as they were viewed as a check on that officer, and because, owing to the prejudices of the time, the attempt would have been represented as impairing the plan already adopted for the payment of the debt. I only tried to simplify the forms, and this was the object of my letter [of March 31, 1802] to the Committee of Ways and Means. The injury which Mr. Pitt’s plan did was to divert the public attention from the only possible mode of paying a debt, viz., a surplus of receipts over expenditures, and to inspire the absurd belief that there was some mysterious property attached to a sinking fund which would enable a nation to pay a debt without the sine qua non condition of a surplus… But the only injury done here by the provisions respecting the commissioners of the sinking fund, and by certain specific appropriations connected with the subject, was to render it more complex, and the accounts of the public debt less perspicuous and intelligible. Substantially they did neither good nor harm. The payments for the public debt and its redemption were not in the slightest degree affected, either one way or the other, by the existence of the commissioners of the sinking fund or by the repeal of the laws in reference to them. The laws making permanent appropriations were much more important. Even with respect to these it is obvious that they must also have become nugatory whenever the expenditure exceeded the income. Still they were undoubtedly useful by their tendency to check the public expenses.”

The letter on the management of the sinking fund, mentioned in the above extract, will be found in the American State Papers55 by readers who care to study the details of American finance. These details have a very subordinate importance; the essential points in Mr. Gallatin’s history are the rules he caused to be adopted in regard to the payment of the debt, and the measures he took to secure revenue with which to make that payment. The rule adopted at his instance secured the ultimate extinction of the debt within the year 1817, provided he could maintain the necessary surplus revenue. The story of Mr. Gallatin’s career as Secretary of the Treasury relates henceforward principally to the means he used or wished to use in order to defend or recover this surplus, and the interest of that career rests mainly in the obstructions which he met and the defeat which he finally sustained.

Nevertheless, it would be very unjust to Mr. Gallatin to imagine that his interest in the government was limited to payment of debt or to details of financial management. He was no doubt a careful, economical, and laborious financier, and this must be understood as the special field of his duty, but he was also a man of large and active mind, and his Department was charged with interests that were by no means exclusively financial. One of these interests related to the public lands.

1802.As has been already seen, the public land system was organized under the previous Administrations, but it took shape and found its great development in Mr. Gallatin’s hands. When the Administration of Mr. Jefferson came into power there were sixteen States in the Union, all of them, except Kentucky and Tennessee, lying on or near the Atlantic seaboard; at that time the Mississippi River bounded our territory to the westward, and the 31st parallel, which is still the northern line of portions of the States of Florida and Louisiana, was our southern boundary until it met the Mississippi. The public lands lay therefore in two great masses, divided by the States of Kentucky and Tenneesee; one of these masses was north of the Ohio River, extending to the lakes, the other west of Georgia, and both extended to the Mississippi. As yet the Indian titles had been extinguished over comparatively small portions of these territories, and in the process of managing her part of the lands the State of Georgia had succeeded in creating an entanglement so complicated as to defy all ordinary means of extrication. One of the first duties thrown upon Mr. Gallatin was that of acting, together with Mr. Madison and Mr. Lincoln, as commissioner on the part of the United States, to effect a compromise with the State of Georgia in regard to the boundary of that State and the settlement of the various claims already existing under different titles. Mr. Gallatin assumed the principal burden of the work, and the settlement effected by him closed this fruitful source of annoyances, fixed the western boundary of Georgia, and opened the way to the gradual development of the land system in the Alabama region. This settlement was the work of two years, but it was so deeply complicated with the famous Yazoo corruptions that fully ten years passed before the subject ceased to disturb politics.

At the same time he took in hand the affairs of the North-Western Territory. The more eastern portion of this vast domain had already a population sufficient to entitle it to admission as a State, and the subject came before Congress on the petition of its inhabitants. It was referred to a select committee, of which Mr. William B. Giles was chairman, and this committee in February, 1802, made a report based upon and accompanied by a letter from Mr. Gallatin.56 The only difficulty presented in this case was that “of making some effectual provisions which may secure to the United States the proceeds of the sales of the western lands, so far at least as the same may be necessary to discharge the public debt for which they are solemnly pledged.” To secure this result Mr. Gallatin proposed to insert in the act of admission a clause to that effect, but in order to obtain its acceptance by the State convention he suggested that an equivalent should be offered, which consisted in the reservation of one section in each township for the use of schools, in the grant of the Scioto salt springs, and in the reservation of one-tenth of the net proceeds of the land, to be applied to the building of roads from the Atlantic coast across Ohio. Congress reduced this reservation one-half, so that one-twentieth instead of one-tenth was reserved for roads; but, with this exception, all Mr. Gallatin’s ideas were embodied in a law passed on the 30th April, 1802, under which Ohio entered the Union. This was the origin of the once famous National Road, and the first step in the system of internal improvements, of which more will be said hereafter.

The details of organization of the land system belong more properly to the history of the new Territories and States than to a biography.57 They implied much labor and minute attention, but they are not interesting, and they may be omitted here. There remains but one subject which Mr. Gallatin had much at heart, and which he earnestly pressed both upon the Administration and upon Congress. This was his old legislative doctrine of specific appropriations, which he caused Mr. Jefferson to introduce into his first message, and which he then seems to have persuaded his friend Joseph H. Nicholson to take in charge as the chairman of a special committee. At the request of this committee, Mr. Gallatin made a statement at considerable length on the 1st March, 1802.58 The burden of this document was that too much arbitrary power had been left to the Secretary of the Treasury to put his own construction on the appropriation laws, and that no proper check existed over the War and Navy Departments; the remedies suggested were specific appropriations and direct accountability of the War and Navy Departments to the Treasury officers. Mr. Nicholson accordingly introduced a bill for these purposes on April 8, 1802, but it was never debated, and it went over as unfinished business. Probably the resistance of the Navy Department prevented its adoption, for the letters of Mr. Gallatin to Mr. Jefferson, quoted above, show how utterly Mr. Gallatin failed in securing the exactness and accountability in that Department which he had so persistently demanded. Nor was this all. Probably nothing was farther from Mr. Gallatin’s mind than to make of this effort a party demonstration. He was quite in earnest and quite right in saying that the practice had hitherto been loose and that it should be reformed, but his interest lay not in attacking the late Administration so much as in reforming his own. Unfortunately, the charge of loose practices under the former Administrations, unavoidable though it was, and indubitably correct, roused a storm of party feeling and even called out a pamphlet from the late Secretary of the Treasury, Wolcott. Mr. Gallatin therefore not only was charged with slandering the late Administration, but was obliged to submit to see the very vices which he complained of in it perpetuated in his own.

These were the great points of public policy on which Mr. Gallatin’s mind was engaged during his first year of office, and it is evident that they were enough to absorb his entire attention. The mass of details to be studied and of operations to be learned or watched completely weighed him down, and caused him ever to look back upon this year as the most laborious of his life. The mere recollection of this labor afterwards made him shrink from the idea of returning to the Treasury when it was again pressed upon him in later years: “To fill that office in the manner I did, and as it ought to be filled, is a most laborious task and labor of the most tedious kind. To fit myself for it, to be able to understand thoroughly, to embrace and to control all its details, took from me, during the two first years I held it, every hour of the day and many of the night, and had nearly brought a pulmonary complaint.”59 Fortunately, his mind was not, in these early days of power, greatly agitated by anxieties or complications in public affairs. The whole struggle which had tortured the two previous Administrations both abroad and at home, the internecine contest between France and her enemies, was for a time at an end; Mr. Madison had nothing on his hands but the vexatious troubles with the Algerine powers, in regard to which there was no serious difference of opinion in America; Congress was mainly occupied with the repeal of the judiciary bill, a subject which did not closely touch Mr. Gallatin’s interests otherwise than as a measure of economy; Mr. Jefferson’s keenest anxieties, as shown in his correspondence of this year, seem to have regarded the distribution of offices and the management of party schisms. After the tempestuous violence of the two last Administrations the country was glad of repose, and its economical interests assumed almost exclusive importance for a time.

It was at this period of his life that Gilbert Stuart painted the portrait, an engraving of which faces the title-page of this volume. Mrs. Gallatin always complained that her husband’s features were softened and enfeebled in this painting until their character was lost. Softened though they be, enough is left to show the shape and the poise of the head, the outlines of the features, and the expression of the eyes. Set side by side with the heads of Jefferson and Madison, this portrait suggests curious contrasts and analogies, but, looked at in whatever light one will, there is in it a sense of repose, an absence of nervous restlessness, mental or physical, unusual in American politicians; and, unless Stuart’s hand for once forgot its cunning, he saw in Mr. Gallatin’s face a capacity for abstraction and self-absorption often, if not always, associated with very high mental power; an habitual concentration within himself, which was liable to be interpreted as a sense of personal superiority, however carefully concealed or controlled, and a habit of judging men with judgments the more absolute because very rarely expressed. The faculty of reticence is stamped on the canvas, although the keen observation and the shrewd, habitual caution, so marked in the long, prominent nose, are lost in the feebleness of the mouth, which never existed in the original. Mr. Gallatin lived to have two excellent portraits taken by the daguerreotype process. Students of character will find amusement in comparing these with Stuart’s painting. Age had brought out in strong relief the shrewd and slightly humorous expression of the mouth; the most fluent and agreeable talker of his time was still the most laborious analyzer and silent observer; the consciousness of personal superiority was more strongly apparent than ever; but the man had lost his control over events and his confidence in results; he had become a critic, and, however genial and conscientious his criticism might be, he had a deeper sense of isolation than fifty years before.

In person he was rather tall than short, about five feet nine or ten inches high, with a compact figure, and a weight of about one hundred and fifty pounds. His complexion was dark; his hair black; but when Stuart painted him he was already decidedly bald. His eyes were hazel, and, if one may judge from the painting, they were the best feature in his face.

Of his social life, his private impressions, and his intimate conversation with the persons most in his confidence at this time, not a trace can now be recovered. Rarely separated from his wife and children, except for short intervals in summer, he had no occasion to write domestic letters, and his correspondence, even with Mr. Jefferson, was for the most part engrossed by office-seeking and office-giving. After some intermediate experiment he at last took a house on Capitol Hill, where he remained through his whole term of office. When the British army entered Washington in 1814, a shot fired from this house at their general caused the troops to attack and destroy it, and even its site is now lost, owing to the extension of the Capitol grounds on that side. It stood north-east of the Capitol, on the Bladensburg Road, and its close neighborhood to the Houses of Congress brought Mr. Gallatin into intimate social relations with the members. The principal adherents of the Administration in Congress were always on terms of intimacy in Mr. Gallatin’s house, and much of the confidential communication between Mr. Jefferson and his party in the Legislature passed through this channel. Nathaniel Macon, the Speaker; John Randolph, the leader of the House; Joseph H. Nicholson, one of its most active members; Wilson Cary Nicholas, Senator from Virginia; Abraham Baldwin, Senator from Georgia, and numbers of less influential leaders, were constantly here, and Mr. Gallatin’s long service in Congress and his great influence there continued for some years to operate in his favor. But the communication was almost entirely oral, and hardly a trace of it has been preserved either in the writings of Mr. Gallatin or in those of his contemporaries. For several years the government worked smoothly; no man appeared among the Republicans with either the disposition or the courage to oppose Mr. Jefferson, and every moment of Mr. Gallatin’s time was absorbed in attention to the duties of his Department, on which the principal weight of responsibility fell.