полная версия

полная версияThe Life of Albert Gallatin

– The New York election has engrossed the whole attention of all of us, meaning by us Congress and the whole city. Exultation on our side is high; the other party are in low spirits. Senate could not do any business on Saturday morning when the intelligence was received, and adjourned before twelve. As to the probabilities of election, they stand as followeth:

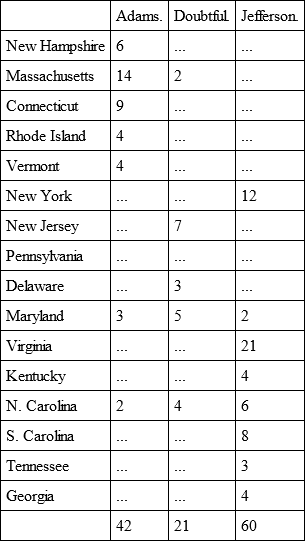

There are 123 electors, supposing Pennsylvania to have no vote. Of these, 62 make a majority. We count 60 for Jefferson certain. If we therefore get only 2 out of the 21 doubtful votes, he must be elected. Probabilities are therefore highly in our favor. Last Saturday evening the Federal members of Congress had a large meeting, in which it was agreed that there was no chance of carrying Mr. Adams, but that he must still be supported ostensibly in order to carry still the votes in New England, but that the only chance was to take up ostensibly as Vice-President, but really as President, a man from South Carolina, who, being carried everywhere except in his own State along with Adams, and getting the votes of his own State with Jefferson, would then be elected. And for that purpose, abandoning Thomas Pinckney, they have selected General Charles Cotesworth Pinckney. I think they will succeed neither in S. Carolina in getting the votes for him, nor in New England in making the people jilt Adams. Who is to be our Vice-President, Clinton or Burr? This is a serious question which I am delegated to make, and to which I must have an answer by Friday next. Remember this is important, and I have engaged to procure correct information of the wishes of the New York Republicans…

JAMES NICHOLSON TO GALLATINMay 6, 1800.Dear Sir, – My situation and health did not permit my writing you during our election, but supposed you received information from Mr. Warner, who I requested would take the task off my hands. That business has been conducted and brought to issue in so miraculous a manner that I cannot account for it but from the intervention of a Supreme Power and our friend Burr the agent. The particulars I have since the election understood, and which justifies my suspicion. His generalship, perseverance, industry, and execution exceeds all description, so that I think I can say he deserves anything and everything of his country; but he has done it at the risk of his life. This I will explain to you when I have the pleasure of seeing you. I am informed he is coming on to you. Perhaps he will be the bearer of this. I shall conclude by recommending him as a general far superior to your Hambletons;48 as much so as a man is to a boy; and I have but little doubt this State, through his means and planning, will be as Republican in the appointment of electors as the State of Virginia.

I have not been able since my being here before to-day to visit my friend and neighbor, Governor Clinton. I understand his health and spirits are both returning. His name at the head of our ticket had a most powerful effect. I cannot inform you what either Burr’s or his expectations are, but will write you more particularly about the governor after my visit…

JAMES NICHOLSON TO GALLATINGreenwich Lane, May the 7th, 1800.Dear Sir, – I have conversed with the two gentlemen mentioned in your letter. George Clinton, with whom I first spoke, declined. His age, his infirmities, his habits and attachment to retired life, in his opinion, exempt him from active life. He (Governor Clinton) thinks Colonel Burr is the most suitable person and perhaps the only man. Such is also the opinion of all the Republicans in this quarter that I have conversed with; their confidence in A. B. is universal and unbounded. Mr. Burr, however, appeared averse to be the candidate. He seemed to think that no arrangement could be made which would be observed to the southward; alluding, as I understood, to the last election, in which he was certainly ill used by Virginia and North Carolina.

I believe he may be induced to stand if assurances can be given that the Southern States will act fairly.

Colonel Burr may certainly be governor of this State at the next election if he pleases, and a number of his friends are very unwilling that he should be taken off for Vice-President, thinking the other the most important office. Upon the whole, however, we think he ought to be the man for V. P., if there is a moral certainty of success. But his name must not be played the fool with. I confidently hope you will be able to smooth over the business of the last election, and if Colonel Burr is properly applied to, I think he will be induced to stand. At any rate we, the Republicans, will make him.

MRS. GALLATIN TO HER HUSBAND7th May, 1800.… Papa has answered your question about the candidate for Vice-President. Burr says he has no confidence in the Virginians; they once deceived him, and they are not to be trusted…

GALLATIN TO HIS WIFE12th May, 1800.… We do not adjourn to-day, but certainly shall to-morrow… We had last night a very large meeting of Republicans, in which it was unanimously agreed to support Burr for Vice-President…

Between the adjournment of Congress in May and his departure for the western country in July, Mr. Gallatin prepared and published another pamphlet on the national finances, which was his contribution to the canvass for the Presidential election of that year. Mr. Wolcott, the Secretary of the Treasury, in a letter to the Committee of Ways and Means, dated January 22, 1800, had expressed the opinion that the principal of the debt had increased $1,516,338 since the establishment of the government in 1789. A committee of the House, on the other hand, had on May 8 reported that the debt had been diminished $1,092,841 during the same period. Mr. Gallatin entered into a critical examination of the methods by which these results were obtained, and then proceeded to test them by applying his own method of comparing the receipts and expenditures. His conclusion was that the nominal debt had been increased by $9,462,264. Two millions of this increase, however, was caused by unnecessary assumption of State debts. But allowing for funds actually acquired by government and susceptible of being applied to reduction of debt, the nominal increase reduced itself to $6,657,319. And since all these results were more or less nominal, he devoted the larger part of his work to an elaborate and searching investigation into the actual receipts and expenditures of the past ten years.

1801.The summer of 1800 was again passed in the western country; the last summer which Mr. Gallatin was to pass there for more than twenty years. With the autumn came the Presidential election, and the dreaded complication occurred by which Mr. Jefferson and Mr. Burr, having received an equal number of electoral votes, became rival candidates for the choice of the House of Representatives. The session of 1800-1801 was almost wholly occupied in settling this dispute. The whole Federalist party insisted upon voting for Burr, and, although not able to elect him, they were able to delay for several days the election of Mr. Jefferson. Mr. Gallatin’s position as leader of the Republicans in the House, and in a manner responsible for the selection of Mr. Burr as candidate for the Vice-Presidency, was one of controlling influence and authority. His letters to his wife give a clear picture of the scene at Washington as he saw it from day to day, but there are one or two points on which some further light is thrown by his papers.

He rarely expressed his opinions of the men with whom he acted. He never expressed any opinion about Colonel Burr. Yet he knew that the Virginians distrusted Burr, and even in his own family, where Colonel Burr was probably warmly admired, there were moments when their faith was shaken. The following letter is an example:

MARIA NICHOLSON TO MRS. GALLATINNew York, February 5, 1801.… As I know you are interested for Theodosia Burr, I must tell you that Mr. Alston has returned from Carolina, it is said, to be married to her this month. She accompanied her father to Albany, where the Legislature are sitting; he followed them the next day. I am sorry to hear these accounts. Report does not speak well of him; it says that he is rich, but he is a great dasher, dissipated, ill-tempered, vain, and silly. I know that he is ugly and of unprepossessing manners. Can it be that the father has sacrificed a daughter so lovely to affluence and influential connections? They say that it was Mr. A. who gained him the 8 votes in Carolina at the present election, and that he is not yet relieved from pecuniary embarrassments. Is this the man, think ye? Has Mr. G. a favorable opinion of this man of talents, or not? He loves his child. Is he so devoted to the customs of the world as to encourage such a match?..

Colonel Burr himself overacted his part. For some private reason Mr. Gallatin was unable to take his seat when Congress met, and it was not till January 12, 1801, that he at last appeared in Washington, to which place the government had been transferred during the summer. The contest, which was to decide the election, took place a month later. Colonel Burr was at New York, about to go up to Albany to perform his duties as member of the Legislature. He felt the necessity of reassuring the minds of his friends at Washington, and he did so from time to time with a degree of off-hand simplicity very suggestive of ulterior thoughts. His first letter to Gallatin is as follows:

AARON BURR TO GALLATINNew York, 16th January, 1801.Dear Sir, – I am heartily glad of your arrival at your post. You were never more wanted, for it was absolutely vacant.

Livingston will tell you my sentiments on the proposed usurpation, and indeed of all the other occurrences and projects of the day.

The short letter of business which I wrote you may be answered to Dallas; anything you may wish to communicate to me may be addressed this city. Our postmaster and that at Albany are “honorable men.”

Yours, A. B.The next is written from Albany, in reply to a letter from Mr. Gallatin, which has not been preserved:

AARON BURR TO GALLATINAlbany, 12th February, 1801.Dear Sir, – My letters for ten days past had assured me that all was settled and that no doubt remained but that J. would have 10 or 11 votes on the first trial; I am, therefore, utterly surprised by the contents of yours of the 3d. In case of usurpation, by law, by President of Senate pro tem., or in any other way, my opinion is definitively made up, and it is known to S. S. and E. L. On that opinion I shall act in defiance of all timid, temporizing projects.

On the 21st I shall be in New York, and in Washington the 3d March at the utmost; sooner if the intelligence which I may receive at New York shall be such as to require my earlier presence.

Mr. Montfort was strongly recommended to me by General Gates and Colonel Griffin. At their request I undertook to direct his studies in pursuit of the law. He left New York suddenly and apparently in some agitation, without assigning to me any cause and without disclosing to me his intentions or views, or even whither he was going, except that he proposed to pass through Washington. Nor had I any reason to believe that I should ever see him again. You may communicate this to Mr. J., who has also written me something about him.

Yours, A. B.Mr. Gallatin in the last years of his life came upon this letter, and endorsed on it, in a hand trembling with age, the following words with a significant mark of interrogation:

“had thought that Jefferson would be elected on first ballot by 10 or 11 votes (out of 16)?”

Burr’s last letter in this connection was written from Philadelphia after the result was decided:

BURR TO GALLATINPhiladelphia, February 25, 1801.Dear Sir, – The four last letters of your very amusing history of balloting met me at New York on Saturday evening. I thank you much for the obliging attention, and I join my hearty congratulations on the auspicious events of the 17th. As to the infamous slanders which have been so industriously circulated, they are now of little consequence, and those who have believed them will doubtless blush at their own weakness.

The Feds boast aloud that they have compromised with Jefferson, particularly as to the retaining certain persons in office. Without the assurance contained in your letter, this would gain no manner of credit with me. Yet in spite of my endeavors it has excited some anxiety among our friends in New York. I hope to be with you on the 1st or 2d March.

Adieu.These letters from Mr. Burr suggest much more than they intentionally express; for if they show that Burr still felt the weight of that Virginia mistrust which had four years previously cost him his place as next in succession to Mr. Jefferson, they show, too, that his confidence in Virginia was scarcely greater than when in May, 1800, he told Commodore Nicholson that the Virginians had once deceived him and were not to be trusted. There was a sting in his remark about the anxiety among his friends in New York. In spite of his efforts to the contrary, they still thought that Mr. Jefferson might have made a bargain with the Federalists. The letters also show that Mr. Gallatin at the very moment denied the existence of any such bargain; with his usual disposition to conciliate, he seems to have coupled together the charges against both candidates as equal slanders. Whether Mr. Gallatin was admitted so far into the confidence of his chief as to know all that was said and done in reference to this election in February, 1801, is a question that may remain open; but that something passed between Mr. Jefferson and General Smith which was regarded by the Federalists as a bargain, is not to be denied. Fortunately, Mr. Gallatin lived to hear all the discussions which rose long afterwards on this subject, and almost the last letter he ever wrote was written to record his understanding of the matter:

GALLATIN TO HENRY A. MUHLENBERGNew York, May 8, 1848.Dear Sir, – A severe cold, which rendered me incapable of attending to any business, has prevented an earlier answer to your letter of the 12th of April.

Although I was at the time probably better acquainted with all the circumstances attending Mr. Jefferson’s election than any other person, and I am now the only surviving witness, I could not, without bestowing more time than I can spare, give a satisfactory account of that ancient transaction. A few observations must suffice.

The only cause of real apprehension was that Congress should adjourn without making a decision, but without usurping any powers. It was in order to provide against that contingency that I prepared myself a plan which did meet with the approbation of our party. No appeal whatever to physical force was contemplated, nor did it contain a single particle of revolutionary spirit. In framing this plan Mr. Jefferson had not been consulted, but it was communicated to him, and he fully approved it.

But it was threatened by some persons of the Federal party to provide by law that, if no election should take place, the executive power should be placed in the hands of some public officer. This was considered as a revolutionary act of usurpation, and would, I believe, have been put down by force if necessary. But there was not the slightest intention or suggestion to call a convention to reorganize the government and to amend the Constitution. That such a measure floated in the mind of Mr. Jefferson is clear from his letters of February 15 and 18, 1801, to Mr. Monroe and Mr. Madison. He may have wished for such measure, or thought that the Federalists might be frightened by the threat.

Although I was lodging in the same house with him, he never mentioned it to me. I did not hear it even suggested by any one. That Mr. Jefferson had ever thought of such plan was never known to me till after the publication of his correspondence, and I may aver that under no circumstances would that plan have been resorted to or approved by the Republican party. Anti-federalism had long been dead, and the Republicans were the most sincere and zealous supporters of the Constitution. It was that which constituted their real strength.

I always thought that the threatened attempt to make a President by law was impracticable. I do not believe that, if a motion had been made to that effect, there would have been twenty votes for it in the House. It was only intended to frighten us, but it produced an excitement out-of-doors in which some of our members participated. It was threatened that if any man should be thus appointed President by law and accept the office, he would instantaneously be put to death. It was rumored, and though I did not know it from my own knowledge I believe it was true, that a number of men from Maryland and Virginia, amounting, it was said, to fifteen hundred (a number undoubtedly greatly exaggerated), had determined to repair to Washington on the 4th of March for the purpose of putting to death the usurping pretended President.

It was under those circumstances that it was deemed proper to communicate all the facts to Governor McKean, and to submit to him the propriety of having in readiness a body of militia, who might, if necessary, be in Washington on the 3d of March for the purpose not of promoting, but of preventing civil war and the shedding of a single drop of blood. No person could be better trusted on such a delicate subject than Governor McKean. For he was energetic, patriotic, and at the same time a most steady, stern, and fearless supporter of law and order. It appears from your communication that he must have consulted General Peter Muhlenberg on that subject. But subsequent circumstances, which occurred about three weeks before the 4th of March, rendered it altogether unnecessary to act upon the subject.

There was but one man whom I can positively assert to have been decidedly in favor of the attempt to make a President by law. This was General Henry Lee, of Virginia, who, as you know, was a desperate character and held in no public estimation. I fear from the general tenor of his conduct that Mr. Griswold, of Connecticut, in other respects a very worthy man, was so warm and infatuated a partisan that he might have run the risk of a civil war rather than to see Mr. Jefferson elected. Some weak and inconsiderate members of the House might have voted for the measure, but I could not designate any one.

On the day on which we began balloting for President we knew positively that Mr. Baer, of Maryland, was determined to cast his vote for Mr. Jefferson rather than that there should be no election; and his vote was sufficient to give us that of Maryland and decide the election. I was certain from personal intercourse with him that Mr. Morris, of Vermont, would do the same, and thus give us also the vote of that State. There were others equally prepared, but not known to us at the time. Still, all those gentlemen, unwilling to break up their party, united in the attempt, by repeatedly voting for Mr. Burr, to frighten or induce some of us to vote for Mr. Burr rather than to have no election. This balloting was continued several days for another reason. The attempt was made to extort concessions and promises from Mr. Jefferson as the conditions on which he might be elected. One of our friends, who was very erroneously and improperly afraid of a defection on the part of some of our members, undertook to act as an intermediary, and confounding his own opinions and wishes with those of Mr. Jefferson, reported the result in such a manner as gave subsequently occasion for very unfounded surmises.

It is due to the memory of James Bayard, of Delaware, to say that although he was one of the principal and warmest leaders of the Federal party and had a personal dislike for Mr. Jefferson, it was he who took the lead and from pure patriotism directed all those movements of the sounder and wiser part of the Federal party which terminated in the peaceable election of Mr. Jefferson.

Mr. Jefferson’s letter to Mr. Monroe dated February 15, 1801, at the very moment when the attempts were making to obtain promises from him, proves decisively that he made no concessions whatever. But both this letter, that to Mr. Madison of the 18th of February, and some others of preceding dates afford an instance of that credulity, so common to warm partisans, which makes them ascribe the worst motives, and occasionally acts of which they are altogether guiltless, to their opponents. There was not the slightest foundation for suspecting the fidelity of the post…

This interesting letter also suggests something more than appears on its surface. Evidently Mr. Gallatin meant to intimate, with as much distinctness as was decent, his opinion that it was not Mr. Jefferson who guided or controlled the result of this election, and that altogether too much importance was attached to what Mr. Jefferson did and said. The election belonged to the House of Representatives, where not Mr. Jefferson but Mr. Gallatin was leader of the party and directed the strategy. The allusion to General Samuel Smith’s intervention is very significant. Evidently Mr. Gallatin considered General Smith to have been guilty of what was little better than an impertinence in having intruded between the House and Mr. Jefferson with “erroneous and improper” fears of the action of men for whom Mr. Gallatin himself was responsible. This was the first occasion on which the Smiths crossed Gallatin’s path, and when he looked back upon it at the end of fifty years it seemed an omen.

Mr. Gallatin considered himself to be, and doubtless was, the effective leader in this struggle. He marshalled the forces; he fought the battle; he made the plans, and in making them he did not even consult Mr. Jefferson, but simply obtained his assent to what had already received the assent of his followers in the House. These plans, alluded to in the Muhlenberg letter, are printed in Mr. Gallatin’s Writings.49 They were framed to cover every emergency. If the Federalists, acting on the assumption of a vacancy in the Presidential office, undertook to fill that vacancy by law, the Republicans were to refuse recognition of such a President and to agree on a uniform mode of not obeying the orders of the usurper, and of discriminating between those and the laws which should be suffered to continue in operation. In case only a new election were the object desired, without usurpation of power in the mean while, submission was on the whole preferable to resistance. An assumption of executive power by the Republicans in any mode not recognized by the Constitution was discouraged, and a reliance on the next Congress was preferred in any case short of actual usurpation. The idea of a convention to reorganize the government was not even suggested.

The crisis lasted until the 17th February, when the Federalists gave way and Mr. Jefferson’s election was quietly effected. With this event Mr. Gallatin’s career in Congress closed.

GALLATIN TO HIS WIFEWashington City, 15th January, 1801.… I arrived here only on Saturday last. The weather was intensely cold the Saturday I crossed the Alleghany Mountains, and afterwards I was detained one day and half by rain and snow… Our local situation is far from being pleasant or even convenient. Around the Capitol are seven or eight boarding-houses, one tailor, one shoemaker, one printer, a washing-woman, a grocery shop, a pamphlets and stationery shop, a small dry-goods shop, and an oyster house. This makes the whole of the Federal city as connected with the Capitol. At the distance of three-fourths of a mile, on or near the Eastern Branch, lie scattered the habitations of Mr. Law and of Mr. Carroll, the principal proprietaries of the ground, half a dozen houses, a very large but perfectly empty warehouse, and a wharf graced by not a single vessel. And this makes the whole intended commercial part of the city, unless we include in it what is called the Twenty Buildings, being so many unfinished houses commenced by Morris and Nicholson, and perhaps as many undertaken by Greenleaf, both which groups lie, at the distance of half-mile from each other, near the mouth of the Eastern Branch and the Potowmack, and are divided by a large swamp from the Capitol Hill and the little village connected with it. Taking a contrary direction from the Capitol towards the President’s house, the same swamp intervenes, and a straight causeway, which measures one mile and half and seventeen perches, forms the communication between the two buildings. A small stream, about the size of the largest of the two runs between Clare’s and our house, and decorated with the pompous appellation of “Tyber,” feeds without draining the swamps, and along that causeway (called the Pennsylvania Avenue), between the Capitol and President’s House, not a single house intervenes or can intervene without devoting its wretched tenant to perpetual fevers. From the President’s House to Georgetown the distance is not quite a mile and a half; the ground is high and level; the public offices and from fifty to one hundred good houses are finished; the President’s House is a very elegant building, and this part of the city on account of its natural situation, of its vicinity to Georgetown, with which it communicates over Rock Creek by two bridges, and by the concourse of people drawn by having business with the public offices, will improve considerably and may within a short time form a town equal in size and population to Lancaster or Annapolis. But we are not there; the distance is too great for convenience from thence to the Capitol; six or seven of the members have taken lodgings at Georgetown, three near the President’s House, and all the others are crowded in the eight boarding-houses near the Capitol. I am at Conrad & McMunn’s, where I share the room of Mr. Varnum, and pay at the rate, I think, including attendance, wood, candles, and liquors, of 15 dollars per week. At table, I believe, we are from twenty-four to thirty, and, was it not for the presence of Mrs. Bailey and Mrs. Brown, would look like a refectory of monks. The two Nicholas, Mr. Langdon, Mr. Jefferson, General Smith, Mr. Baldwin, &c., &c., make part of our mess. The company is good enough, but it is always the same, and, unless in my own family, I had rather now and then see some other persons. Our not being able to have a room each is a greater inconvenience. As to our fare, we have hardly any vegetables, the people being obliged to resort to Alexandria for supplies; our beef is not very good; mutton and poultry good; the price of provisions and wood about the same as in Philadelphia. As to rents, I have not yet been able to ascertain anything precise, but, upon the whole, living must be somewhat dearer here than either in Philadelphia or New York. As to public news, the subject which engrosses almost the whole attention of every one is the equality of votes between Mr. Jefferson and Mr. Burr. The most desperate of the Federalists wish to take advantage of this by preventing an election altogether, which they may do either by dividing the votes of the States where they have majorities or by still persevering in voting for Burr whilst we should persevere in voting for Jefferson; and the next object they would then propose would be to pass a law by which they would vest the Presidential power in the hands of some man of their party. I believe that such a plan if adopted would be considered as an act of usurpation, and would accordingly be resisted by the people; and I think that partly from fear and partly from principle the plan will not be adopted by a majority. But a more considerable number will try actually to make Burr President. He has sincerely opposed the design, and will go any lengths to prevent its execution. Hamilton, the Willing and Bingham connection, almost every leading Federalist out of Congress in Maryland and Virginia, have openly declared against the project and recommend an acquiescence in Mr. Jefferson’s election. Maryland, which if decided in our favor would at once make Mr. J. President (for we have eight States sure, – New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, and Georgia), is afraid about the fate of the Federal city, which is hated by every member of Congress without exception of persons or parties; and I know that if a vote was to take place to-day we would obtain the vote of that State. Even Bayard from Delaware and Morris from Vermont (this last I suspect under the influence of Gouv. Morris) are inclined the same way. The vote of either is sufficient to decide in our favor. And from all those circumstances I infer that there will be an election, and that in favor of Mr. Jefferson. If not, there will be either an interregnum until the new Congress shall meet and then a choice made in favor of him also, or in case of usurpation by the present Congress (which of all suppositions is the most improbable), either a dissolution of the Union if that usurpation shall be supported by New England, or a punishment of the usurpers if they shall not be supported by New England. In every possible case I think we have nothing to fear. The next important object is the convention with France, which hangs in the Senate. The mercantile interest, Mr. Adams and Mr. Hamilton are in favor of its ratification. Yet I think it rather probable that either a decision will be postponed or that it shall be clogged by the rejection or modification of some articles, an event which might endanger the whole. I understand that Great Britain does not take any offence at the treaty itself, and that being the case, although I dislike myself several parts of the instrument, I see no sufficient reason why we should not agree to it…