полная версия

полная версияThe Life of Albert Gallatin

… I have been overwhelmed with business since my last to you. I have been obliged to correct for the press two speeches on the navy, which I enclose; you will find, however, that they are not written by me but by Gales, and although correct in point of sense are not so as to style. I have also written one on the subject of the alien bill, and in addition to that I have had our goods to select and sundry political meetings to attend on the subject of our next election for governor. Thos. McKean is to be our man, and James Ross the other… Do you want a dish of politics till I see you? The President nominated Mr. Murray minister to France with powers to treat, with instructions that he should not go from Holland to Paris until he should have received assurances of being met by a similar envoy; and he sent along with it a letter from Talleyrand to the secretary of the French legation at the Hague, in which, referring to some former conversations of the secretary with Murray, he added that they would lead to a treaty, and that the French government were ready to admit any American envoy as the representative of a free, great, and independent nation. Murray, I guess, wanted to make himself a greater man than he is by going to France and treating, and wrote privately, it is said, to the President on the subject. The President, without consulting any of his Secretaries, made the nomination. The whole party were prodigiously alarmed. Porcupine and Fenno abused the old gentleman. The nomination instead of being approved was in the Senate committed to a select committee. They then attacked so warmly the President that he sent a new nomination of Ellsworth, P. Henry, and Murray, and none of them to go until assurances are received here that France will appoint a similar envoy. Which will postpone the whole business six months at least…

The summer and autumn of 1799 were passed at New Geneva, and when Mr. Gallatin returned to Philadelphia for the session of 1799-1800, he brought his wife with him, and they kept house in Philadelphia till the spring. There were therefore no domestic letters written during this season, and his repugnance to writing was such that even the letters he received were chiefly filled with grumbling at his silence. There seems at no time before 1800 to have been much communication by writing between Mr. Gallatin and the other Republicans. One or two unimportant letters from Edward Livingston, Matthew L. Davis, Walter Jones, or Tench Coxe, are all that remain on Mr. Gallatin’s files. The long series of Mr. Jefferson’s notes or letters, most carefully preserved, begin only in March, 1801. The same is true of Mr. Madison’s and Mr. Monroe’s. Mr. Gallatin had no large constituency of highly-educated people to correspond with him; he was greatly occupied with current business; his own State of Pennsylvania was the seat of government, and its affairs were carried on directly by word of mouth. Mr. Jefferson, the leader of the party, did attempt by correspondence and by personal influence to produce some sort of combination in its movements, but sharp experience taught him to remain as quiet as possible, and his relations were chiefly with his confidential Virginia friends. In this respect the Federalists were much better organized than their rivals.

1800.It is unfortunate, too, that the debates of the Sixth Congress, from December, 1799, to March, 1801, should have been very poorly reported; indeed, hardly reported at all. Yet the winter of 1799-1800 was so much less important than those which preceded and followed it, that the loss may not be very serious. The death of General Washington a few days after Congress met had a certain momentary effect in diverting the current of public thought. The attitude of the President occupied the attention of his own party, and the probability, which approached a certainty, of peace with France, paralyzed the armaments. Mr. Gallatin himself was not disposed to press his economies too strongly. “I was averse,” he said in debate, “to the general system of hostility adopted by this country; but once adopted, it is my duty to support it until negotiation shall have restored us to our former situation or some cogent circumstances shall compel a change. At present I think it proper that the system of hostility and resistance should continue, and I would vote against any motion to change that system. At the same time I am of opinion that a naval establishment is too expensive for this country, but, as we have assumed an attitude of resistance, it would be wrong to change it at present.” His opinion was that a reduction should be made in the army to the extent of $2,500,000, which would, he thought, still leave a deficiency of an equal amount to be provided for by a loan.

It was in connection with this motion to reduce the army that Mr. Harper made a speech, of which the following passage is a portion:

… “Sir, we never need be, and I am persuaded never shall be, taxed as the English are. A very great portion of their permanent burdens arises from the interest of a debt which the government most unwisely suffered to accumulate almost a century, without one serious effort or systematic plan for its reduction. Her present minister, at the commencement of his administration in 1783, established a permanent sinking fund, which now produces very great effects; he also introduced a maxim of infinite importance in finance which he has steadily adhered to, that whenever a new loan is made the means shall be provided not only of paying the interest but of effecting a gradual extinction of the principal. Had these two ideas been adopted and practised upon at the beginning of the century which we have just seen close, England might have expended as much money as she has expended and not owed at this moment a shilling of debt, except that contracted in the present war. These ideas, profiting by the example of England, we have adopted and are now practising on. We have provided a fund which is now in constant operation for the extinguishment of our debt. This fund will extinguish the foreign debt in nine years from now, and the six per cent., a large part of our domestic debt, in eighteen years. I trust we shall adhere to this plan, and whenever we are compelled by the exigency of our affairs to make a loan, by providing also for its timely extinguishment, we may always avoid an inconvenient or burdensome accumulation of debt. We may gather all the roses of the funding system without its thorns.”

This was the theory of the English financiers, of William Pitt and his scholars, which held possession of the English exchequer throughout the French war and was only exploded in 1813 by a pamphlet written by a Scotchman named Hamilton.47 Mr. Gallatin, however, was never its dupe. He answered Mr. Harper on the spot; and short as his reply was, it gave in perfectly clear language the substance of all that fourteen years later was supposed to be a new discovery in English finance:

… “I know but one way that a nation has of paying her debts, and that is precisely the same which individuals practise. ‘Spend less than you receive, and you may then apply the surplus of your receipts to the discharge of your debts. But if you spend more than you receive, you may have recourse to sinking funds, you may modify them as you please, you may render your accounts extremely complex, you may give a scientific appearance to additions and subtractions, you must still necessarily increase your debt. If you spend more than you receive, the difference must be supplied by loans; and if out of these receipts you have set a sum apart to pay your debts, if you have so mortgaged or disposed of that sum that you cannot apply it to your useful expenditure, you must borrow so much more in order to meet your expenditure. If your revenue is nine millions of dollars and your expenditure fourteen, you must borrow, you must create a new debt of five millions. But if two millions of that revenue are, under the name of sinking fund, applicable to the payment of the principal of an old debt, and pledged for it, then the portion of your revenue applicable to discharging your current expenditures of fourteen millions is reduced to seven millions; and instead of borrowing five millions you must borrow seven; you create a new debt of seven millions, and you pay an old debt of two. It is still the same increase of five millions of debt. The only difference that is produced arises from the relative price you give for the old debt and rate of interest you pay for the new. At present we pay yearly a part of a domestic debt bearing six per cent. interest, and of a foreign debt bearing four or five per cent. interest; and we may pay both of them at par. At the same time we are obliged to borrow at the rate of eight per cent. At present, therefore, that nominal sinking fund increases our debt, or at least the annual interest payable on our debt.” …

The two speeches made by Mr. Harper and Mr. Gallatin on this occasion, the 10th January, 1800, were very able, and are even now interesting reading; but they find their proper place in the Annals of Congress, and the question of the reduction of the army was to be settled by other events. A matter of a very different nature absorbed the attention of Congress during the months of February and March. This was the once famous case of Jonathan Bobbins, a British sailor claiming to be an American citizen, who, having committed a murder on board the British ship-of-war Hermione, on the high seas, had escaped to Charleston, and under the 27th article of the British treaty had been delivered up by the United States government. At that time extradition was a novelty in our international relations. The President was violently attacked for the surrender, and a long debate ensued in Congress. Mr. Gallatin spoke at considerable length, but his speech is not reported, and although voluminous notes, made by him in preparing it, are among his papers, it is impossible to say what portion of these notes was actually used in the speech. The triumphs of the contest, however, did not fall to him or to his associates, but to John Marshall, who followed him, and who, in a speech that still stands without a parallel in our Congressional debates, replied to him and to them. There is a tradition in Virginia that after Marshall concluded his speech, the Republican members pressed round Gallatin, urging with great earnestness that it should be answered at once, and that Gallatin replied in his foreign accent, “Gentlemen, answer it yourselves; for my part I think it unanswerable,” laying the stress on the antepenultimate syllable. The story is probably true. At all events, Mr. Gallatin made no answer, and Mr. Marshall’s argument settled the dispute by an overwhelming vote.

But the coming Presidential election, one of the most interesting in our history, now cast its shadow in advance over the whole political field. The two parties were so equally divided that the vote of New York City would probably decide the result, and for this reason the city election of May, 1800, was the turning-point of American political history in that generation. There the two party champions, Hamilton and Burr, were pitted against each other. Commodore Nicholson was hotly engaged, and Edward Livingston, Matthew L. Davis, and the other Republican politicians of New York became persons of uncommon interest. Mr. Gallatin, as leader of the Republican party in Congress and as closely connected by marriage with the Republican interests of New York City, was kept accurately informed of every step in the political campaign. He himself was in constant communication with Matthew L. Davis, who was Burr’s most active friend then and ever afterwards. Davis’s letters are now of historical importance, and may be compared with the narrative in his subsequent Life of Burr:

MATTHEW L. DAVIS TO GALLATINNew York, March 29, 1800.Dear Sir, – I yesterday saw a family letter of yours developing the views of the Federal party; with many of the facts contained in that letter I was previously acquainted, but I was in some measure at a loss to account for certain proceedings of the supreme Legislature; this letter completely unmasks the party. Your opinion respecting the importance of our election for members of Assembly in this city is the prevailing opinion among our Republican friends. You ask, “What are your prospects?” All things considered, they are favorable. We have been so much deceived already that a prudent man perhaps will not hazard an opinion but with extreme diffidence. At the request of Mr. Nicholson, I shall briefly state the leading features of our plan.

You are already acquainted with the circumstances which so much operated against us at the last election: the tale of the ship Ocean, Captain Kemp; the Manhattan Company; the contemplated French invasion; the youth of many of our candidates, &c., &c. These things, united with bank influence and bank jealousy, had a most astonishing effect. The bank influence is now totally destroyed; the Manhattan Company will in all probability operate much in our favor; and it is hoped the crew of the Ocean will not again be murdered; but this is not all: a variety of trifling acts passed during the session of the former Legislature were also brought forward and adapted to the purposes of the party. Menaces from the Federal party had also a great influence. I think they will not dare to use them at the approaching election.

The Federalists have had a meeting and determined on their Senators; they have also appointed a committee to nominate suitable characters for the Assembly. Out of the thirteen that now represent the city, eleven decline standing again. They are much perplexed to find men. Mr. Hamilton is very busy, more so than usual, and no exertions will be wanting on his part. Fortunately, Mr. Hamilton will have at this election a most powerful opponent in Colonel Burr. This gentleman is extremely active; it is his opinion that the Republicans had better not publish a ticket or call a meeting until the Federalists have completed theirs. Mr. Burr is arranging matters in such a way as to bring into operation all the Republican interest. He is not to be on our nomination, but is to represent one of the country counties. At our first meeting he has pledged himself to come forward and address the people in firm and manly language on the importance of the election and the momentous crisis at which we have arrived. This he has never done at any former election, and I anticipate great advantages from the effect it will produce.

In addition to this, he has taken great trouble to ascertain what characters will be most likely to run well, and by his address has procured the assent of eleven or twelve of our most influential friends to stand as candidates. Among the number are:

On the whole, I believe we shall offer to our fellow-citizens the most formidable list ever offered them by any party in point of morality, public and private virtue, local and general influence, &c., &c. From this ticket and the exertions that indisputably will be made we have a right to expect much, and I trust we shall be triumphant. If we carry this election, it may be ascribed principally to Colonel Burr’s management and perseverance. Hamilton fears his influence; the party seem in a state of consternation, while ours possess more than usual spirits. Such are our prospects. We shall open the campaign under the most favorable impressions, and headed by a man whose intrigue and management is most astonishing, and who is more dreaded by his enemies than any other character in our [ ]. Excuse, sir, this hasty scrawl; I have no time to copy…

MATTHEW L. DAVIS TO GALLATINNew York, April 15, 1800.Tuesday night, 11 o’clock.Dear Sir, – Well knowing the importance of the approaching election in this city, and consequently the anxiety which you and every friend to our country must experience on the subject, I am highly gratified in affording you such information on the occasion as will be interesting and pleasing. The eyes of our friends and of our enemies are turned towards us; all unite in the opinion that if the city and county of New York elect Republicans they will most assuredly have it in their power to appoint Republican electors for President and Vice-President. The counties of Westchester and Orange have selected the most respectable and influential advocates for the rights of the people their respective towns afforded. But of our adversaries in this city. This evening, agreeably to public notice, a meeting was held; the assembly was small, and not attended by either Colonels Hamilton or Troup, two gentlemen who are generally most officious on these occasions. I have already stated to you in a former letter that jealousies and schisms existed among them. This fact has not only been evinced in their numerous caucuses, but they have been doomed to the mortification of bringing the matter this night before the public. A few of their most active men had determined on Philip Brazier as a candidate for the Assembly. Mr. Brazier is a man of very little influence and very limited understanding; he is, however, a Republican, but composed of such pliable materials as will enable his leaders to mould him to almost any form. A large majority of the Federal committee were opposed to him, but his adherents possessing stronger lungs and being vociferous at one of their caucuses, he was carried.

A division took place in the same committee on another subject, viz., who was the most proper candidate for Congress. Some supported Colonel J. Morton, while others as furiously supported William W. Woolsey; both gentlemen consented to stand; as the committee could not agree owing to their divisions, it was resolved to report both candidates to the meeting and let them make their election. Accordingly the two names were publicly brought forward this night, and after much confusion and litigation it was determined by a majority of only 15 or 20 that Jacob Morton should be the candidate for Congress, while the adherents of Mr. Woolsey bawled aloud, “Morton shall not be the man.” Next came the Assembly ticket. It was agreed to without opposition, excepting in the case of Mr. Brazier. He was again violently opposed, and a large majority appeared against him; yet the chairman being a military commander (Brigadier-General Jared Hughes), he decided that it was carried in favor of Mr. Brazier. In this temper the meeting separated. So much for the friends of good order and regular government.

FEDERAL TICKETFor CongressJacob Morton, Esq.

For AssemblymenPeter Schermerhorn, ship-chandler.

Jno. Bogert, baker.

Gabriel Furman, nothing. The man who whipped the ferryman in Bridewell, and on account of whom Kettletas was imprisoned.

John Croleus, Jun., potter.

Philip Ten Eyck, bookseller, late clerk, present partner of Hugh Gaine.

Isaac Burr, grocer.

Samuel Ward, a bankrupt endeavoring to settle his affairs by paying 000 in the pound.

C. D. Colden, assistant attorney-general.

James Tyler, shoemaker.

Philip Brazier, lawyer.

N. Evertson, lawyer.

Isaac Sebring, grocer, one of the firm Sebring & Van Wyck.

Abraham Russel, mason.

A private meeting of our friends was held this evening at the house of Mr. Brockholst Livingston; about forty attended; we determined on calling the Republicans together on Thursday evening next, and for that purpose sent advertisements to the different printers. The prevailing opinion was that we should appoint a committee at that meeting to withdraw for half an hour, form a ticket, and return and report, so that on Friday morning we shall most probably publish. Never have I observed such an union of sentiment, so much zeal, and so general a determination to be active. Indeed, on presenting the Federal ticket to our meeting (for we had friends who attended theirs) all was joy and enthusiasm. Our ticket is complete, and stands as follows:

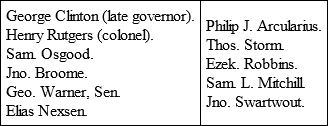

CongressDr. Samuel L. MitchillAssemblyGeo. Clinton.

Horatio Gates.

Henry Rutgers.

Thomas Storm.

Samuel Osgood.

Geo. Warner, Senior.

John Broome.

Philip J. Arcularius.

Ezekiel Robins.

Brockholst Livingston.

John Swartwout.

James Hunt.

Elias Nexsen.

The late hour at which I write this will be a sufficient apology for the scrawl…

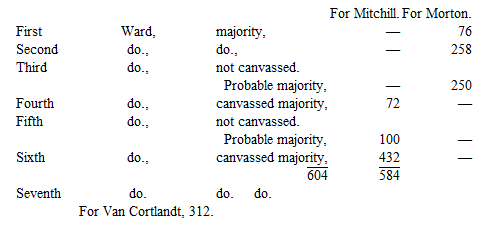

MATTHEW L. DAVIS TO GALLATINThursday night, 12 o’clock.May 1, 1800.REPUBLICANISM TRIUMPHANTDear Sir, – It affords me the highest gratification to assure you of the complete success of the Republican Assembly ticket in this city. This day the election closed, and several of the wards have been canvassed for Congress; the result as follows:

Thus, sir, it is probable Mr. Mitchill is elected a member of Congress, and no doubt can remain but our whole Assembly, ticket is elected by a majority of three hundred and fifty votes. To Colonel Burr we are indebted for everything. This day has he remained at the poll of the Seventh Ward ten hours without intermission. Pardon this hasty scrawl; I have not ate for fifteen hours.

With the highest respect, &c.P.S. – Since writing the above I learn from undoubted authority that Mr. Mitchill is elected by upwards of one hundred majority.

MATTHEW L, DAVIS TO GALLATINNew York, May 5, 1800.Dear Sir, – I have already informed you of the complete triumph which we have obtained in this city, – a triumph which I trust will have some influence in promoting the rights of the people and establishing their liberties on a permanent basis. Our country has arrived at an awful crisis. The approaching election for President and Vice-President will decide in some measure on our future destiny. The result will clearly evince whether a republican form of government is worth contending for. On this account the eyes of all America have been turned towards the city and county of New York. The management and industry of Colonel Burr has effected all that the friends of civil liberty could possibly desire.

Having accomplished the task assigned us, we in return feel a degree of anxiety as to the characters who will probably be candidates for those two important offices. I believe it is pretty generally understood that Mr. Jefferson is contemplated for President. But who is to fill the Vice-President’s chair? I should be highly gratified in hearing your opinion on this subject; if secrecy is necessary, you may rely on it; and, sir, as I have no personal views, you will readily excuse my stating the present apparent wishes and feelings of the Republican party in this city.

It is generally expected that the Vice-President will be selected from the State of New York. Three characters only can be contemplated, viz., Geo. Clinton, Chancellor Livingston, and Colonel Burr.

The first seems averse to public life, and is desirous of retiring from all its cares and toils. It was therefore with great difficulty he was persuaded to stand as candidate for the State Legislature. A personal interview at some future period will make you better acquainted with this transaction. In addition to this, Mr. Clinton grows old and infirm.

To Mr. Livingston there are objections more weighty. The family attachment and connection; the prejudices which exist not only in this State, but throughout the United States, against the name; but, above all, the doubts which are entertained of his firmness and decision in trying periods. You are well acquainted with certain circumstances that occurred on the important question of carrying the British treaty into effect. On that occasion Mr. L. exhibited a timidity that never can be forgotten. Indeed, it had its effect when he was a candidate for governor, though it was not generally known.

Colonel Burr is therefore the most eligible character, and on him the eyes of our friends in this State are fixed as if by sympathy for that office. Whether he would consent to stand I am totally ignorant, and indeed I pretend not to judge of the policy farther than it respects this State. If he is elected to the office of V. P., it would awaken so much of the zeal and pride of our friends in this State as to secure us a Republican governor at the next election (April, 1801). If he is not nominated, many of us will experience much chagrin and disappointment. If, sir, you do not consider it improper, please inform me by post the probable arrangement on this subject. I feel very anxious. Any information you may wish relative to our election I will at all times cheerfully communicate.