полная версия

полная версияOperas Every Child Should Know

By the time the song was sung, Lionel had quite lost his head.

"Martha, since the moment I first saw thee, I have loved thee madly. Be my wife and I will be your willing slave – you may count on me to do the spinning and everything else, if only you will be my wife. I'll raise thee to my own station." This was really too much. Martha looked at him in amazement.

"Raise me – er – " In spite of herself she had to laugh. Then, with a feeling of tenderness growing in her heart, she felt sorry for him.

"I am sorry to cause you pain, but really you don't know what you are saying. I – " And at this crisis Nancy and Plunkett came in, Plunkett raising a great to-do because Nancy had been hiding successfully from him, in the kitchen.

"She hasn't been cooking," he explained; "simply hiding – and I can't abide idle ways – never could – now what is wrong with you two?" he asks, observing the restraint felt by Lionel and Martha; but before any one could answer, midnight struck.

"Twelve o'clock!" all exclaimed.

"All good angels watch over thee," Lionel said impulsively to Martha, "and make thee less scornful."

For a moment, Plunkett looked thoughtful, then turning to Nancy he said manfully, while everybody seemed at pause since the stroke of midnight.

"Nancy, girl, you are not what I sought for – a good servant – but some way, I feel as if – as if as a wife, I should find thee a good one. I vow, I begin to love thee, for all of thy bothersome little ways."

"Well, well, good-night, good-night, sirs," Nancy cried hastily and somewhat disconcerted. To tell the truth, she had begun to think kindly of Plunkett. Plunkett went thoughtfully to the outer door and carefully locked it, then turned and regarded the girls who stood silently and a little sadly, apart.

"Good-night," he said: and Lionel looking tenderly at Martha murmured, "Good-night," and the two men went away to their own part of the house, leaving the girls alone.

"Nancy – " Martha whispered softly, after a moment.

"Madame?"

"What next? – how escape?"

"How can we go?"

"We must – "

"It is very dark and the way is strange to us," she said, sadly and fearfully.

"Well, fortune has given us gentle masters, at least," Martha murmured.

"Yes – kind and good – "

"What if the Queen should hear of this?"

"Oh, Lord!" And at that moment came a soft knocking at the window. Both girls started. "What's that?" More knocking! "Gracious heaven! I am nearly dead with fear," Martha whispered, looking stealthily about. Nancy pointed to the window.

"Look – " Martha looked.

"Tristram – Sir Tristram!" she whispered excitedly. "Open the window. I can't move, I am so scared. Now, he'll rave – and I can't resent it. We deserve anything he may say." Nancy opened the window, and Sir Tristram stepped in softly, upon receiving a caution from the girls.

"Lady Harriet, this is most monstrous."

"Oh, my soul! Don't we know it. Don't wake the farmers up, in heaven's name! Things are bad enough without making them worse."

"Yes, let us fly, and make as little row about it as we can," Nancy implored.

"Then come – no words. I have my carriage waiting; follow me quickly and say good-bye to this hovel."

"Hovel?" Lady Harriet looked about. Suddenly she had a feeling of regret. "Hovel?"

"Nay," Nancy interrupted. "To this peaceful house – good-bye." Nancy, too, had a regret. They had had a gleeful hour here, among frank and kindly folk, even if they had also been a bit frightened. Anything that had gone wrong with them had been their fault. Tristram placed a bench at the window that the ladies might climb over, and thus they got out, and immediately the sound of their carriage wheels was heard in the yard. Plunkett had waked up meantime and had come out to call the girls. It was time for their day's work to begin. Farmer folk are out of bed early.

"Ho, girls! – time to be up," he called, entering from his chamber. Then he saw the open window. He paused. "Do I hear carriage wheels – and the window open – and the bench – and the girls – gone! Ho there! Everybody!" he rushed out and furiously pulled the bell which hung from the pole outside. His farmhands come running. "Ho – those girls hired yesterday have gone. Get after them. Bring them back. I may drop dead the next instant, but I'll be bound they shan't treat us in this manner. After them! Back they shall come!" And in the midst of all this confusion in ran Lionel.

"What – "

"Thieves! – the girls have run off – a nice return for our affections!"

"After them! – don't lose a minute," Lionel then cried in his turn, and away rushed the farmhands.

"They are ours for one year, by law. Bring them back, or ye shall suffer for it. Be off!" And the men mounted horses and went after the runaways like the wind.

"Nice treatment!"

"Shameful!" Plunkett cried, dropping into a chair, nearly fainting with rage.

ACT IIIPlunkett's men had hunted far and wide for the runaways, but without success. The farmer was still sore over his defeat: he felt himself not only defrauded, but he had grown to love Nancy, and altogether he became very unhappy. One day he was sitting with his fellow farmers around a table in a little forest inn, drinking his glass of beer, when he heard the sound of hunting horns in the distance.

"Hello! a hunting party from the palace must be out," he remarked, but the music of the horn which once pleased him could no longer arouse him from his moodiness. Nevertheless an extraordinary thing was about to happen. As he went into the inn for a moment, into the grove whirled – Nancy! all bespangled in a rich hunting costume and accompanied by her friends who were enjoying the hunt with her. They were singing a rousing hunting chorus, but Martha – Lady Harriet – was not with them.

"What has happened to Lady Harriet?" some one questioned of Nancy, who was expected to know all her secrets.

"Alas – nothing interests her ladyship any more," she replied! Nancy knew perfectly well that, ever since their escapade, Harriet had thought of nothing but Lionel. For Nancy's part, she had not thought of much besides Plunkett; but she did not mean to reveal the situation to the court busybodies. Then while the huntresses were roaming about the inn, out came Plunkett! and Nancy, not perceiving at first who he was, went up to him and began to speak.

"Pray, my good man, can you tell – Good heaven!" she exclaimed, recognizing him; "Plunkett!"

"Yes, madame, Plunkett; and now Plunkett will see if you get the better of him a second time. We'll let the sheriff settle this matter, right on the spot."

"Man, you are mad. Do not breathe my name or each huntress here shall take aim and bring you down. Ho, there!" she cried distractedly to her friends; and she took aim at Plunkett, while all of the others closed round him. It was then Plunkett's turn to beg for mercy.

"They're upon me, they've undone me!" he cried. "This is serious," and so indeed it was. "But oh, dear me, there is a remarkable charm in these girls, even if they do threaten a man's life," and still looking back over his shoulder, away he ran, pursued by the girls. They had no sooner gone than Lionel came in. He was looking disconsolately at the flowers to which Martha sang the "Last Rose of Summer." He himself sang a few measures of the song and then looked about him.

"Ah," he sighed, thinking still of Martha:

[Listen]

None so rare,None so fair,Yet enraptur'd mortal heart;Maiden dear.Past compare,Oh, 'twas death from thee to part!Ere I saw thy sweet faceOn my heart there was no traceOf that love from above,That in sorrow now I prove;but alas, thou art gone,And in grief I mourn alone;Life a shadow doth seem,And my joy a fleeting dream,A fleeting dream.None so rare, etc.

And after he had sung thus touchingly of Martha, he threw himself down on the grass, and remained absorbed in his thoughts. But while he was resting there, Lady Harriet and Sir Tristram had also wandered thither. At first they did not see Lionel.

"I have come here away from the others, in order to be alone," Harriet declared impatiently.

"Alone with me?" Sir Tristram asked indiscreetly.

"Good heaven – it doesn't matter in the least whether you are here or elsewhere. I am quite unconscious of you, wherever you are," she replied, not very graciously. "Do go away and let me alone!" and, finding that he could not please her, Tristram wandered off, and left her meditating there. After a while she began to sing to herself, softly, and Lionel recognized the voice.

"It is she! – Martha!" he cried, starting up. Harriet recognized him, and at once found herself in a dreadful state of mind.

"What shall I do? It is Lionel! that farmer I hired out to!" Well! It was Lionel's opportunity, and he fell to making the most desperate love to her – which she liked very much, but which, being a high-born lady of Queen Anne's Court, she was bound to resent. She called him base-born and a good many unpleasant things, which did not seem to discourage him in the least, even though it made him feel rather badly; but while he was still protesting his love, Tristram returned, and at once believed Harriet to be in the toils of some dreadful fellow. So he called loudly for everybody in the hunt to come to the rescue – which was about the most foolish thing he could do. Then all set upon Lionel. Plunkett, hearing the row, rushed in.

"Stand by me!" Lionel cried.

Nancy appeared. "What does this mean?" she in turn demanded in a high-handed manner.

"Julia, too," Lionel shouted, recognizing her.

"Bind this madman in fetters," Tristram ordered.

"Don't touch him," Plunkett threatened.

"I shall die," Nancy declared.

"I engaged these girls in my service," Lionel shouted, "and now they wish to break the bargain!"

"What?" everybody screamed, staring at Nancy and Harriet. Tristram and the hunters laughed, Tristram trying to shield the girls and turn it into a joke.

"Have compassion on this madman"; Harriet pleaded wincing when she saw Lionel bound and helpless. Lionel then reproached her. She knew perfectly that she deserved it and felt her love for him growing greater. Everybody was in a most dreadful state of mind. Then a page rushed in and cried that Queen Anne was coming toward them, and immediately Lionel had an inspiration.

"Take this ring to her Majesty – quick," he cried, handing his ring to Plunkett.

A litter was then brought for Lady Harriet. She, heartbroken, stepped into it. Lionel was pinioned and was being dragged off. Plunkett held up the ring, to assure him that it should straightway be taken to the Queen.

ACT IVAfter the row had quieted down and Nancy and Harriet got time to think matters over, Harriet reached the conclusion that she could not endure Lionel's misfortune. Hence she had got Nancy to accompany her to the farmer's house. When they arrived some new maid whom the farmers had got opened the door to them.

"Go, Nancy, and find Plunkett, Lionel's trusty friend, and tell him I am repentant and cannot endure Lionel's misfortunes. Tell him his friend is to have hope," and, obeying her beloved Lady Harriet, Nancy departed to find Plunkett and give the message. In a few minutes she returned with the farmer. He now knew who the ladies were and treated Harriet most respectfully.

"Have you told him?" Lady Harriet asked.

"Yes, but we cannot make Lionel understand anything. He sits vacantly gazing at nothing. He has had so much trouble, that probably his brain is turned."

"Let us see," said Harriet; and instantly she began to sing, "'Tis the Last Rose."

While she sang, Lionel entered slowly. He had heard. Harriet ran to him and would have thrown herself into his arms, but he held her off, fearing she was again deceiving him.

"No, no, I repent, and it was I who took thy ring to the Queen! I have learned that thy father was a nobleman – the great Earl of Derby; and the Queen sends the message to thee that she would undo the wrong done thee. Thou art the Earl of Derby – and I love thee – so take my hand if thou wilt have me."

Well, this was all very well, but Lionel was not inclined to be played fast and loose with in that fashion. When he was a plain farmer, she had nothing of this sort to say to him, however she may have felt.

"No," he declared, "I will have none of it! Leave me, all of you," and he rushed off, whereupon Harriet sank upon a bench, quite overcome. Then suddenly she started up.

"Ah – I have a thought!" and out she flew. While she was gone, the farmer and Nancy, who had really begun to care greatly for each other, confessed their love.

"Now that our affairs are no longer in confusion, let us go out and walk and talk it over," Plunkett urged, and, Nancy being quite willing, they went out. But when they got outside they found to their amazement that Plunkett's farmhands were rushing hither and thither, putting up tents and booths and flags, and turning the yard into a regular fair-ground, such as the scene appeared when Lionel and Harriet first met. Some of the girls on the farm were assuming the rôle of maids looking for service, and, in short, everything was as nearly like the original scene as they could possibly make it in a short time.

"What, what is all this?" Plunkett asked, amazed. Then he learned it was all done by Harriet's orders, and he and Nancy began to understand. Then Harriet came in, dressed as Martha. Nancy ran off and returned dressed as Julia, and then all was complete.

"There is Lionel coming toward us," Nancy cried. "What will happen now?" and there he came, led sadly by Plunkett. He looked about him, dazed, till Plunkett brought up Lady Harriet and presented her as a maid seeking work.

"Heaven! It is Martha – "

"Yes, is this not enough to prove to thee that I am ready to renounce my rank and station for thee? Here I am, seeking thy service," she pleaded.

"Well, good lassies, what can ye do?" Plunkett asked, entering into the spirit of the thing, and then Nancy gaily sang:

I for spinning finest linen, etc.Lady Harriet gave Lionel some flowers and then began "'Tis the Last Rose." Then presently, Lionel, who had been recovering himself slowly while the play had been going on, joined in the last measures, and holding out his arms to Lady Harriet, the lovers were united. Nancy and Plunkett were having the gayest sort of a time, and everybody was singing at the top of his voice that from that time forth there should be nothing but gaiety and joy in the world; and probably that turned out to be true for everybody but old Sir Tristram, who hadn't had a stroke of good luck since the curtain rose on the first act!

HUMPERDINCK

THIS composer of charming music will furnish better biographical material fifty years hence. At present we must be satisfied to listen to his compositions, and leave the study of the man to future generations.

HÄNSEL AND GRETEL

CHARACTERS OF THE OPERA

The story takes place in a German forest.

Composer: E. Humperdinck.

Author: Adelheid Wette.

ACT IOnce upon a time, in a far-off forest of Germany, there lived two little children, Hänsel and Gretel, with their father and mother. The father and mother made brooms for a living, and the children helped them by doing the finishing of the brooms.

The broom business had been very, very bad for a long time, and the poor father and mother were nearly discouraged. The father, however, was a happy-go-lucky man who usually accepted his misfortunes easily. It was fair-time in a village near the broom-makers' hut, and one morning the parents started off to see if their luck wouldn't change. They left the children at home, charging them to be industrious and orderly in behaviour till they returned, and Hänsel in particular was to spend his time finishing off some brooms.

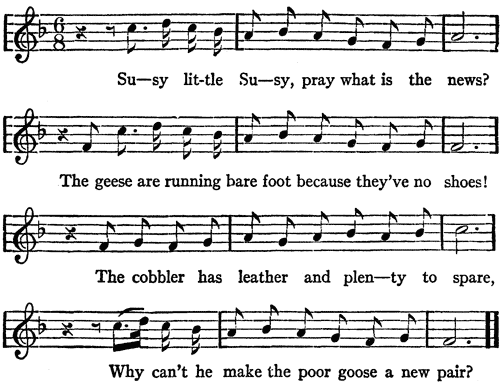

Now it is the hardest thing in the world for little children to stick to a long task, so that which might have been expected happened: Hänsel and Gretel ceased after a little to work, and began to think how hungry they were. Hänsel was seated in the doorway, working at the brooms; brooms were hanging up on the walls of the poor little cottage; and Gretel sat knitting a stocking near the fire. Being a gay little girl, she sang to pass the time:

[Listen]

Susy little Susy, pray what is the news?The geese are running bare foot because they've no shoes!The cobbler has leather and plenty to spare,Why can't he make the poor goose a new pair?

This sounded rather gay, and, before he knew it, Hänsel had joined in:

Eia popeia, pray what's to be done?Who'll give me milk and sugar, for bread I have none?I'll go back to bed and I'll lie there all day,Where there's naught to eat, then there's nothing to pay."Speaking of something to eat – I'm as hungry as a wolf, Gretel. We haven't had anything but bread in weeks."

"Well, it does no good to complain, does it? Why don't you do as father does – laugh and make the best of it?" Gretel answered, letting her knitting fall in her lap. "If you will stop grumbling, Hänsel, I'll tell you a secret – it's a fine one too." She got up and tiptoed over to the table. "Come here and look in this jug," she called, and Hänsel in his turn tiptoed over, as if something very serious indeed would happen should any one hear him.

"Look in that jug – a neighbour gave us some milk to-day, and that is likely to mean rice blanc-mange."

"Oh, gracious goodness! I'll be found near when rice blanc-mange is going on; be sure of that. How thick is the cream?" the greedy fellow asked, dipping his finger into the jug.

"Aren't you ashamed of yourself! Take your fingers out of that jug, Hänsel, and get back to your work. You'll get a good pounding if mother comes home and finds you cutting up tricks."

"No, I'm not going to work any more – I'm going to dance."

"Well, I admit dancing is good fun," Gretel answered him reluctantly. "We can dance a little, and sing to keep us in time, and then we can go back to work."

Brother, come and dance with me,Both my hands I offer thee,Right foot first,Left foot then,Round about and back again,she sang, holding out her hands.

"I don't know how, or I would," Hänsel declared, watching her as she spun about.

"Then I'll teach you. Just keep your eyes on me and I'll teach you just how to do it," she cried, and then she began to dance. Gretel told him precisely how to do it, and Hänsel learned very well and very quickly. Then they danced together, and in half a minute had forgotten all about going back to their work. They twirled and laughed and sang and shouted in the wildest sort of glee, and at last, perfectly exhausted with so much fun, they tumbled over one another upon the floor, and were laughing too hard to get up. Just at this moment, when they had actually forgotten all about hunger and work, home came their mother. She opened the door and looked in.

"For mercy's sake! what goings on are these?" she cried.

"Why, it was Hänsel, he – "

"Gretel wanted to – " they both began, scrambling to their feet.

"That will do. I want to hear nothing from you. You are the most ill-behaved children in the world. Here are your father and I slaving ourselves to death for you, and not a thing do you do but dance and sing from morning till night – "

"It would be awfully nice to eat, too," Hänsel replied reflectively.

"What's that you say, you ungrateful child? Don't you eat whenever the rest of us do?" However harsh she seemed, the mother was only angry at the thought of there being nothing in the house to eat, and she felt so badly to think the children were hungry that she made a dive at Hänsel to slap him, when – horrors! she knocked the milk off the table, broke the jug, and all the milk went streaming over the floor. This was indeed a misfortune. There they stood, all three looking at their lost supper.

"Now see what you have done?" she screamed angrily at the children. "Get yourselves out of here. If you want any supper you'll have to work for it. Take that basket and go into the wood and fill it with strawberries, and don't either of you come home till it is full. Dear me, it does seem as if I had trouble enough without such actions as yours," the distracted mother cried; and quite unjustly she hustled the children and their basket outside the hut and off into the wood.

They had no sooner gone out than the poor, distracted woman, exhausted with the day's tramping and unsuccessful effort to sell her brooms, sat at the table weeping over the lost milk; and finally she fell asleep. After a while a merry song was heard in the wood, and the father presently appeared singing, at the very threshold. Really, for a hungry man with a hungry family and nothing for supper, he was in a remarkably merry mood.

"Ho, there, wife!" he called, and then entered with a great basket over his shoulder. He saw the mother asleep and stopped singing. Then he laughed and went over to her.

"Hey, wake up, old lady, hustle yourself and get us a supper. Where are the children?"

"What are you talking about," the mother asked, waking up and looking confused at the noise her husband was making. "I can't get any supper when there is nothing to get."

"Nothing to get? – well, that is nice talk, I'm sure. We'll see if there is nothing to get," he answered, roaring with laughter – and he began to take things out of his basket. First he took out a ham, then some butter. Flour and sausages followed, and then a dozen eggs; turnips, and onions, and finally some tea. Then at last the good fellow turned the basket upside down, and out rolled a lot of potatoes.

"Where in the world did all of these things come from?" she cried.

"I had good luck with my brooms, when all seemed lost, and here we are with a feast before us. Now call the children and let us begin."

"I was so angry because the milk got spilt that I sent them off to the woods for berries and told them not to come home till they had a basket full. I really thought that was all we should have for supper." At this the father looked frightened.

"What if they have gone to the Ilsenstein?" he cried, jumping up and taking a broom from the wall.

"Well, what harm?" the wife inquired, "and why do you take the broom?"

"What harm? Do you not know that it is the awful magic mountain where the old witch who eats little children dwells? – and do you not know that she rides on a broomstick. I may need one to follow her, in case she has got the children."

"Oh, heavens above! What a wicked woman I was to send the children out. What shall we do? Do you know anything more about that awful ogress?" she demanded of her husband, trembling fit to die.

An old witch within that wood doth dwell,And she's in league with the powers of hell.At midnight hour,When nobody knows,Away to the witches' dance she goes.Up the chimney they fly,On a broomstick they hie,Over hill and dale,O'er ravine and vale,Through the midnight airThey gallop full tear,On a broomstick, on a broomstickHop, hop, hop, hop, the witches!And by day, they say,She stalks around,With a crinching, crunching, munching sound.And children plump, and tender to eat,She lures with magic gingerbread sweet.On evil bent,With fell intent,She lures the children, poor little things,In the oven hot,She pops the lot.She shuts the door down,Until they're done brown – all those gingerbread children."Oh, my soul!" the poor woman shrieked. "Come! We must lose no time: Hänsel and Gretel may be baked to cinders by this time," and out she ran, screaming, and followed by the father, to look for those poor children.

ACT IIAfter wandering all the afternoon in the great forest, and filling their basket with strawberries, Hänsel and Gretel came to a beautiful mossy tree-trunk where they concluded to sit down and rest before going home. They had wandered so far that they really didn't know that they were lost, but as a matter of fact they had no notion of where they were. Without knowing it, they had gone as far as the Ilsenstein, and that magic place was just behind them, and sunset had already come. As usual, the gay little girl was singing while she twined a garland of wild flowers. Hänsel was still looking for berries in the thicket near. Pretty soon they heard a cuckoo call, and they answered the call gaily. The cuckoo answered, and the calls between them became lively.