полная версия

полная версияThe Church of Grasmere: A History

This is clearly a copy of but a part of the original charter, and the "consideration" which Henry received does not transpire; but in the following month the two speculators procured a licence to sell again, and they passed over their purchase of the Grasmere advowson, and of all woods upon the premises – meaning no doubt the old demesne of the Lindesay Fee – to Alan Bellingham, gent., for £30 11s. 51⁄2 d.98 Bellingham in the same year purchased direct from the Crown that portion of Grasmere known as the Lumley Fee – thus gaining the lordship of some part of the valley.

Henry's sale of the advowson did not touch the tithes, which were left in the hands of the rector; but he reserved for himself the "pension" of 21⁄2 marks which had been regularly paid out of them to the abbey. It passed down with other Crown property to Charles II., and in his reign was sold, according to an Act of Parliament which was passed permitting the sale of such royal proceeds. Since that time it has been in private hands, and bought and sold in the money market like stocks. It may perhaps be traced by sundry entries in account books, as paid by the tithe-holder: in 1645, "for a pension for Gresmire due at Mich: last" £1 13s. 4d. It was paid in 1729 by Dr. Fleming as "Fee-farm Rent" to the Marquis of Caermarthen; and later by Mr. Craike to the Duke of Leeds; while Sir William Fleming, as owner of the tithes of Windermere, paid the same from them.99 It is still paid through a London agent, being officially set down as "Net Rent for Grasmere, £1. 6s. 8d.: Land tax, 6s. 8d." This sum represents – not five marks – but five nobles, or half-marks. Thus it may be said that the dead hand of Henry VIII. still controls the tithes of Grasmere.

This tyrant wrought other changes for Grasmere. When creating the new diocese of Chester, he swept our parts of Westmorland within it. The archdeaconry of Richmondshire remained, but the archdeacon was shorn of power. He no longer instituted our parson, as in the days prior to the rule of St. Mary's Abbey, and this empty form fell to the Bishop of Chester; who, on the death of parson Holgill in 1548, appointed to the office one Gabriel Croft, upon nomination by the patron.100

Now Croft was seemingly a man of unscrupulous temper. The boy Edward was by this time upon the throne, and spoliation of church revenues was, under his advisers and in the name of Protestantism, the order of the day. The parson of Grasmere was one of those who seized the opportunity offered by the general misrule; and he committed an act for which there could be no legal pretext. Previous rectors had drawn the tithes of the parish, and pocketed the large margin that remained, after the stipends of the worthy curates who did their work had been paid. But Croft went beyond this. In 1549 he sold the tithes on a lease, and not for the period of his life (which he might have claimed as his right) but for ninety-seven years. The purchaser was his patron, Dame Marion Bellingham of Helsington, widow; and she paid him a lump sum of £58 11s. 51⁄2 d., upon the agreement that she and her heirs would furnish from the tithes a stipend for the rector of £18 11s. 7d.101

The bargain, ratified by John, Bishop of Chester, was excellent for both parties; but it was disastrous for the parish. So far, the tithes, however mismanaged, had lain in the hands of the church and the clergy, for whose support they were rendered. The Abbey of St. Mary, while exacting a pension from them, exercised in return a supervision that was doubtless of benefit; for under it, the rector – though he took the bulk of them himself – could hardly escape providing the three priests resident within the parish with sufficient stipends. Moreover, as he was an absentee, it is probable that he made a stable arrangement for their ingetting, that would be convenient to himself and comfortable for the parishioners (such as obtained later), and that he even farmed them to the dalesmen themselves. This method saved him the risks of an annual tithing carried out by a paid agent, and it insured him a regular (if more moderate) income, in easily transported silver money. The evidence of the lawsuits shows that the system of paying a certain fixed sum instead of the tenth in kind was actually in force for some commodities, while in some cases this composition or prescription extended to the whole of a landed estate.

The change was sharp, from church control to control by a lay improprietor, whose simple business it was to squeeze as large an income as he could out of his investment. He was not likely to leave the tithing on the old easy footing, nor was the parishioner inclined to increase his offering without resistance. Squire William Fleming was a big enough man to front on his own account the common foe. Averring that, in satisfaction of all tithes the customary annual sum of 20s. had been paid for "the demeanes of Rydall," he refused Alan Bellingham's demand for a tenth of hay, wool and lambs taken from the yearly yield. Alan, who denied the custom, sued him in the Consistory Court at York, including in his claim the proceeds of the years 1569 to 1572, for which payment had been made. The spiritual court judged in his favour; whereupon Fleming carried the case to the civil court of King's Bench. Here, after several adjournments, and a trial before justices connected with the county, the final verdict was given in his favour (1575).102

Before the case was settled, the contenders struck a bargain, and the ownership of the advowson of Grasmere passed from Alan Bellingham of Fawcet Forrest, executor of Marion Bellingham, to the Rydal squire for the sum of £100, and that of the remainder of the lease of the rectory and tithes for £500.103 The tenfold increase of the purchase money in twenty-four years time shows the enormous increase in tithe value when in the grasp of lay hands; for a rise of agricultural prosperity would not account for it. Squire William now became in his turn the oppressor; but the tale of the powerful opposition he roused in the parish must be left to another chapter. The advowson remains yet in his family.

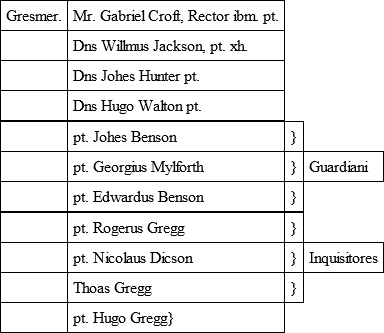

To return to the parsons. Croft, with an annuity assured to him, and a small capital in gold, no doubt troubled himself little about his parish. He had defrauded it and crippled its funds for the next hundred years. The curates we suppose stuck to their posts, though where their stipends came from is a problem. Little change in ritual could have been made, before Edward's death and Mary's accession brought a reinstitution of the old form of faith, as well as a hopeless attempt to restore stolen church property. In 1554 the Bishop of Chester held a visitation at Kendal for these parts, and the officials of the parish are set down in the following list: —104

It is clear from this that three curates then served the parish – "Dominus" being the latinized "sir" of the customary title. Of the third in the list evidence is found in the parish register, where the burial is recorded on March 8th, 1577, of "Hugh Watson preist," this no doubt being the correct form of his name. It seems likely that he officiated in Ambleside, which by this time was a thriving little town. Of John Hunter nothing further is known: he may have served the chapel in Langdale.

Record of William Jackson is found in his will: —105

Sir William Jackson late curet at Gresmer.

Jan. 21, 1569. I William Jackson clarke and curat of Grysmer – to be buriede within ye parishe church of Grysmer, near where my IJ brothers was buried – To my parishe church VIs. VIIId. And yt to be payd… Kendaill for a booke at I bought of (erased) to the betering of the… To the poor folkes XXXs. to be divided at the sytct of my supervisores. Item I give to every on of my god children, VId. – To every sarvent in my maister's house XIId. Item I geve to Sir Thomas Benson a sernet typet. To my Mr. John Benson a new velvet cap – By me Sir William Jaikson at Grysmer.

Inventory, 21 Jan. 1569. – Rament unbequested to be sold be my executores and supervisores. A worsate jaccate, a brod cloth jacate, a brod clothe side goune, a mellay side goune, a shorte goune, a preiste bonate, a velvate cape, a sylke hate, II. pare of hosse, a mellay casseck, a worsat typat, a matras, a great chiste, a ledder dublat. Summa, III li. XIIs… In wax and sergges, books and parchment, with other small thyngs to be sold within my chamber. I owe to Christofor Wolker's wyff Under Helme XIIs. of newe money to be payed to hyr, whych she dyd bowrere for me in my tyme of nede.

The following extract from the Kendal Corporation MSS. may not be inappropriate here: —

MSS. of the Corporation of Kendal.

This MS. commences 10th Report.

Sept. 26, 1653. Prov. at election of a Mayor. Order that every Alderman shall provide a gowne for the following Sunday, or be fined 40s. Gowns according to an ancient order, to be all of one form "of blacke stuffe, to be faced with black plush or velvet, and Mr. Maior himselfe to have one readie against Sunday next or else forfeit 40s."

(A 13). "Abstract of fines of Leete Courte," Oct. 20, 1612. Various penalties for misdemeanours.

"Abstracte of Fines for the Bilawes Courte," Dec. 14, 1612. Various injunctions and fines.

"Offerings and bridehowes allowed by Mr. Alderman" (then head of Corporation) and 4 Burgesses and the Vicar then being. Bidden dinners or "nutcastes, or merie nightes" for money not to exceed 12 persons. Same for "churching dinner" for monie taking, only 12 wives allowed.

From this will something may be gathered of the life of the village priest who belongs to the vale, and whose simple wish is to be buried by his two brothers within the church. He has his appointed chamber in his master's house – doubtless the rectory. His possessions are few. There are some books, also parchment and wax, for the making of wills and indentures; there is the mattress on which he slept, and a great "chiste," in which no doubt papers and clothes were stored together. Of clothes he had a goodly stock, in jackets, gowns, tippets, caps, and the stout leather doublet which no doubt he donned for his long tramps through storm and rain and snow to the dying. The sale of all these was to furnish money for his legacies – for coin he had none. His benefactions are characteristic: loyally to his parish church a noble, or half a mark; to every servant of his master 12d.; to each of his godchildren 6d.; and he desires besides that an old debt, incurred in his "tyme of nede," should be paid in new money. Some crisis is suggested here, when the good wife of Under Helm collected money for him.

But other facts may be gathered from this will. Our good curate bequeaths to "Sir Thomas Benson" his sarsnet tippet, clearly from its superior stuff, the best that he had. This, the usual outer dress of the priest, was a long garment made with sleeves, reaching to the ankles, and was tied with a girdle.106 Now a Thomas Benson, "curate," witnessed the will of John Benson of Baisbrowne in 1563; he must then have served the chapel of Langdale for a series of years. Also it seems probable that the curate's master, John Benson, was the rector, succeeding Croft or another.

A spirit of peace and goodwill breathes through this document, and one too that suggests continuity in the order of the church. Yet it must be remembered that it was written in the reign of Elizabeth, when the Protestant religion had been firmly established by law, and written moreover by a man who had undoubtedly followed the Catholic ritual fifteen years before. His fellow curate too of that date, "preist" Watson, was still alive, surviving him by eight years. There is a Protestant odour about the cassock, and Jackson possessed one; but his wardrobe is distinctly of the old-world, priestly type. It is probable indeed that there was little change made for some time even in the services of the church. The people of the north-western mountains were conservative, and it was they who most stoutly resisted the suppression of the monasteries. There is evidence to show that the new tenets were but slowly adopted in these parts. The church at Crosthwaite was found as late as 1571 to be still in possession of the furniture and pictures that had lent a touch of splendour to the former ritual; and they were then most stringently ordered to be destroyed.107

The people were not likely to welcome changes that brought in their train not only impoverishment of service, but reduction in the number of the clergy; for with the diversion of the tithes, there ceased to be any provision for the salaries of curates.

Langdale did without a curate, and not until over 200 years was the township once more blessed with a resident minister, though the chapel was used for services. Ambleside was in different case. Now a thriving little town, equally distant from the two parish churches that claimed it, with fulling mills bringing in wealth, it was able to maintain a curate independently, and did so.

James Dugdale the cleric, who witnessed a Rydal deed in 1575, might have been supposed to serve at Ambleside, only that Priest Watson was then alive. Certain it is that in 1584 the townsfolk placed their support of chapel and curate on a solid basis, pledging each man his portion of land thereto. This was immediately before the appointment of John Bell as curate. The pledge was repeated in a deed of the year 1597.

The rector of the parish, with no more than £18 odd as stipend, had now to perform the entire duty of the wide parish. Nothing is known of Croft's later dealings with the rectorate, nor of Lancelot Levens, who followed him. But on the latter's death in 1575, John Wilson was instituted, and for fifty-two years he served as rector. From his handwriting, seen in the market-deed, and from the register (most negligently kept during his time of office) an unfavourable impression is created. When he died in 1627, there followed – after a few months interlude, when Robert Hogge served – the Rev. Henry Wilson, B.A., who was to become notorious as a Royalist and High-Churchman. He was nominated by Dame Agnes Fleming, the clever widow of Squire William, who at this time ruled at Rydal Hall for her son John.

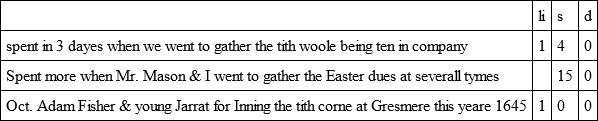

The expenses of the tithe gathering were not great. An item of 2s. 0d. is paid to David Harrison, the Rydal inn-keeper, against "tythinge," and "for gathering tith Eggs" 1s. 0d. These last offerings were paid in kind, and we know from subsequent accounts that this persuasive office was somtimes filled by women, "two wiues," being paid in 1643 "for goeing 3 dayes gathering Eggs at Easter."

The later account-sheets kept by Richard Harrison show less completely than Tyson's the income derived from the tithes.

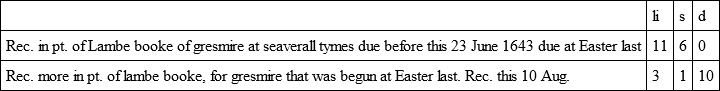

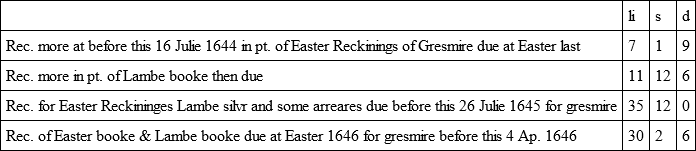

The tithes on lambs amounted therefore in 1643 to £14. 7s. 10d. Next year: —

We have no entries discriminating between tithe and demesne wool, which was now selling at a high price; nor do we hear of the tithe corn, except that in 1643 the sum of 10s. 0d. was paid for the hire of a barn for it. In Tyson's accounts the even money received for it – as well as other entries which connect its payment with the holder of Padmire in Grasmere – give an appearance of it having been then farmed, as it was at a later time.

THE CIVIL WARS

It is clear that the tithes were dropping in value; and this is little to be wondered at when the condition of the country is considered.

War was rife, and the "troubles" that affected every household – high and low, either in actual fighting or in tax-paying – were felt with peculiar poignancy at Rydal Hall. Squire John Fleming, as a rich man, had not stooped to conceal his religion, and had cheerfully paid his fine of £50 a year as a Catholic of the old faith. He died on February 27, 1643, at an unfortunate time for his young children, when warfare was just beginning in the north-west. He was buried the same evening, like many another recusant, in Grasmere Church; and though Parson Henry Wilson was paid a fee for "ouersight of his buriall" it is possible that mass was first said over the body in the "Chapel" chamber at Rydal; for one Salomon Benson, a mysterious member of the group of papists gathered about the Squire, in receipt of a pension of five marks a year, was probably a priest.

The orphaned children – two girls growing to womanhood and a younger boy – were now left with all the wealth that would be eventually theirs, in charge of executors. Chief among these was Richard Harrison, a nephew of the Squire, and a Roman Catholic. He appears to have lived with his wife and son at Rydal Hall, and to have had entire management of the household in the years that followed.

The position was a difficult one, and naturally grew more so as time went on, and success began to attend the Parliamentary party. The money-coffers of Squire John were freely dipped into for loans to support the Royal cause, which the young heir joined in person; and the house was the resort of Royalist soldiers and gentlemen of the neighbourhood. As a consequence, it was peculiarly obnoxious to the supporters of the Parliament, and was likewise detested by the Puritans as a hotbed of Papists. Therefore, when the houses of Royalists were sacked up and down the county, there was little probability that it would escape.

A tradition has always existed that Rydal Hall was entered and plundered by the soldiers of the Commonwealth; but it is in the account-sheets of Richard Harrison that explicit evidence of the fact has now, and for the first time, been found. The catastrophe would belong wholly to Rydal history, but for a clause in the accounts which concerns Grasmere church.

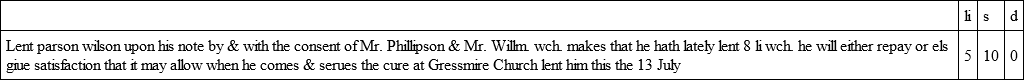

Dates are difficult to follow in the sheets, but it is clear that the year 1644 marked the turning-point of the war. The hopes of the Royalists had been high when Prince Rupert marched through Lancashire to meet the enemy; but they were crushed by the terrible defeat of Marston Moor on July 1st. The king's forces in these parts were completely scattered, and there was a tremendous exodus of loyalists, who left to join the king's army in the south. The band was led by Sir Francis Howard, and it included the young heir of Rydal. The exodus is marked in the account-sheets by the numerous sums borrowed from the Rydal chests by various people, beginning with the chief himself. Even the loyal parsons borrowed, and small sums were lent about this time to two of the Cumberland curates, who possibly went off on king's business too. Henry Wilson, the rector of Grasmere, was a noted Royalist, and apparently acted as an emissary in the cause. The following entry records one of the many loans to him, at a time when he too was leaving the country: —

It is clear that in this year, 1644, the hall and its inmates shared in the general sufferings. Friendly messengers rode by night to give warning when another hall was sacked. Hostile soldiers were quartered on the premises, and some pillaging of horses and other things was done, for which Harrison tried to obtain restitution. He also sought protection – if it might be granted by wire-pulling and bribery – from Colonels Bellingham and Briggs, who commanded the Scots troops in Westmorland. It is possible that the new glass required both for the hall and for the choir of Grasmere church, "which was broken," may have been the result of some hostile demonstration.

But the actual raid upon the hall was made at Eastertide, 1645. The soldiers of "Captaine Orfer & Collonell Lawson" entered it, searched for money and took all they could find (which was little) and carried off Richard Harrison to prison, where he remained till Pentecost.

Further mischief is recorded in another paragraph of the sheets, when the sum of £2 4s. 8d. is set down at Easter, 1645, as "pd. for bread and wine twice at Gresmire Church in regard it was once plundered by Lawson's souldiers."

Now this provision for the Easter communion, which the tithe-holder was bound to make, was a special provision, always accounted for separately, and probably delivered direct to the church from the wine merchant, whose name is occasionally mentioned. So in this case, the church itself was presumably entered with violence, and by the same troop that visited Rydal Hall.

It was a Cumberland troop that did the mischief, as is evident from the names of the officers. Colonel Wilfred Lawson of the Isell family was an ardent fighter for the Parliament. Captain Orfeur was doubtless a member of the stock of Plumbland Hall.108

The troop may have marched from the siege of Carlisle Castle, which had been held for the king through the winter; and nothing is more likely than that, on their march over the Raise, they would halt at Grasmere, and do what despite they could to a sacred building held by an episcopalian parson and a recusant patron, who were of course odious for their so-called "delinquency." The event, however, is inferred rather than actually stated in Harrison's account.109

At Whitsuntide, on his release from prison, Richard Harrison returned to his post at Rydal Hall as factotum and financier. The position became steadily worse. Young William Fleming had returned from Bristol, after reverses in the south, only to be captured and imprisoned in Kendal; and his freedom had to be procured by a heavy ransom. In restless mood he declared his intention of going overseas, and considerable sums were paid for his fitting out; but he never got beyond London, where he died shortly after of smallpox. The Parliamentary Committee, then sitting at Kendal, exacted heavy fines from the estate for delinquency. Oppressive taxes too were repeatedly levied for the support of the Parliamentary forces and the Scotch army. This extraordinary outflow of money, as well as the loans made to friends, must have materially reduced the wealth of Squire John, and have left less for the suitors who presently appeared to claim the hands of the heiresses.

Not the Rydal estate alone, but the whole country-side groaned under the burden of taxation. It is therefore not surprising that from the hardness of the times, as well as from possible illwill, the tithes began to yield an uncertain return; and that to come by them at all it was sometimes necessary to engage a strong man or a stout party for the business. An item in the account-sheets for 1645 runs: —

Adam Fisher was the Rydal blacksmith, and doubtless a strong man. Clearly no farmer could be found to take up a contract for the tithes of corn; and as we have seen, a barn had been hired for its housing.

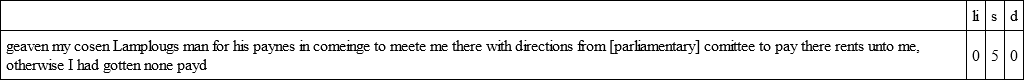

In 1648 Harrison went into Cumberland, and spent a week getting the "tith-rents" due on St. Mark's Day; and he enters: —

Harrison was subjected to another imprisonment, and squeezed by the hostile government of many further sums. His account-sheets close in 1648-9, when the hall – soon to lie under the ban of sequestration – was itself closed.

THE COMMONWEALTH

The year 1645 marked the beginning of a great change in the church government of Grasmere. Already the new system devised by the Presbyterian party (which was now in the ascendant after the success of the Scotch at Newcastle) was being put into force as a substitute for episcopal rule. The division of the country into sections, each called a classis– to be administered by a committee of laymen empowered to nominate for each parish a minister and four elders – was very rapidly carried out. The following answer was sent to the Parliament's demand, by letter from the Speaker, that classes for South Westmorland should be formed: —110

Honourable Sir

We received your Honours letter (dated the 22nd September last) the 3d of February last Wherein is required of us with advise of Godly Ministers, to returne to your Honour such Ministers and Elders as are thought fitt for the Presbiteriall way of Government (which wee much desire to be established) and the several classes. After wee received your Honours letter to that purpose (though long after the date) wee speedily had a meeting; and upon due consideration nominated the Ministers and Elders which wee thought fitted (as your Honour may conceive by this enclosed) for the Presbiteriall imployment as is desired and have divided the County of Westmerland into two Classes. Since the expediting of this your Honours direction: Wee have heard of an Ordinance of Parliament directing to the election of such persons: But as yet neither Order or Ordinance hath come unto us; Only your Honours letter, is our Warrant and Instruction; And accordingly we make bould to send (here inclosed) the names both of Ministers and Elders. And if we faile in the Parliaments method in this particuler, Wee shall willingly (upon your Honours next direction) rectify any mistake for the present, and shalbe willing to submitt to your Honours and Parliamentary directions; Which wee shall duly expect, that in wharsoever wee haved missed, wee may amend it. Thus with our Service recommended Wee remaine