полная версия

полная версияThe Church of Grasmere: A History

But the high valuation of 1292 did not hold good. Complaints from the northern clergy that through impoverishment by various causes, but chiefly the invasions of the Scots, they were by no means able to pay so high a tax, produced some amelioration. A correction was made in 1318, when Windermere was written down at £2 13s. 4d., and Grasmere at £3 6s. 8d., or five marks. And at this figure it remained.

It stood indeed at five marks in 1283, when the first mention of the church occurs in connection with the secular lordship.

Editor's NoteThe writing down of the value of the tithes of Grasmere was the subject of correspondence between the author and myself, and she writes: "The so called taxation of Pope Nicholas IV. was acknowledged to be too high for the Northern Counties; but the reduction of Grasmere, when the alteration was made in 1318, from £16 to five marks (£3 6s. 8d.) is unaccountable to me." It had stood at this figure previously but had been raised to £16, and, as will be seen in the text, as early as 1301 in the reign of Edward I., when the abbot of St. Mary's, York, was allowed to appropriate "the chapels of Gresmer and Wynandermere," Gresmer is described as being worth £20. In 1344, at the Archbishop's Visitation, it is described as worth 5 marks; only to be again raised in 1435. In that year upon the death of John, duke of Bedford and earl of Kendal, to whom they had been granted by his father, Henry IV., we find among the items of his property "the advowsons of Wynandermere and Gressemere each of which is worth £20 yearly." After this the tithes again reverted to 5 marks and in the reign of Henry VIII. the "pension" paid to the abbey is put down as only half of that sum, viz. £1 13s. 4d. at which it still remains.

The terms "pension" and "advowson" may not always mean the same thing, thus advowson seems to be used sometimes as synonymous with tithe. Hence Miss Armitt writes "The parish churches, such as Kendal, Grasmere, etc., were "taxed" from the twelfth century onward at a certain figure – ten marks (£6 13s. 4d.) £16 or £30. What did this taxation represent? The absolute sum to be paid by the rector from the tithes to king, pope, archdeacon, court, or feudal lord? or was it a valuation only of the tithes, from which was calculated the amounts of the various 'scots' or annual payments to ecclesiastical or temporal authorities?" It seems not unlikely that the rise from £3 6s. 8d. to £20 in the reign of Edward I. may be accounted for by the fact that the "Old Valor" which was granted by authority of Innocent the fourth to Henry III. in 1253 was superseded in 1291 by the "New Valor" granted to Edward I. by Nicholas IV., so that when Henry IV. granted the chapels of Grasmere and Windermere to his son John they were valued in 1435 at £20 each. They were only being put back to the sum named in the "New Valor" of 1291 which had been allowed in 1344 to drop to the 5 marks at which they had stood in the "Old Valor." The tithe taxation as established by the "New Valor" remained in force until Henry VIII. But a "Nova Taxatio" which only affected part of the province of York was commanded in 11 Edward II. (1317) on account of the invasion of the Scots and other troubles. These various taxings will account for the variation in payments which were collected for the benefit of the king.

W.F.R.THE PATRONS

William Rufus, upon his conquest of Carlisle, gave over to Ivo de Tailbois all these parts as a fief. After Ivo a confusion of tenure and administration prevails, into which it is useless to enter. The line of patrons of Grasmere may perhaps be begun safely with Gilbert fitz Reinfred, who married Helwise, daughter and heiress of William de Lancaster II., because it was he who first held the Barony of Kendal in chief from Richard I., by charter dated 1190.59

His son William, called de Lancaster III., died in 1246 without a direct heir; and the children of his sisters, Helwise and Alice, shared the fief between them. It is Alice's line that we have to follow. She married William de Lindesey, and her son Walter took that portion of the barony which was later known as the Richmond Fee, and which included the advowson of our church.

Sir William de Lindesey, his son, was the next inheritor. After his death, in 1283, a jury of true and tried men declared that he had died possessed of "A certain chapel there (Gresmer) taxed yearly at 66s 8d."60 The chapel of Windermere, set down at a like sum, belonged to the same lordship.

Christiana, William's heiress, was then only 16. She was married to a Frenchman, Ingelram de Gynes, lord of Coucy. There is evidence that they spent a considerable part of their time in these parts, their seat being at Mourholm, near Carnforth. Ingelram indeed fought in the Scottish wars, as did his son William. Christiana survived her husband some ten years. They had at least four sons, William, Ingelram, Baldwin, and Robert. It was William who inherited the chief part of Christiana's property in the barony of Kendal, which was declared (1334) to include the manor of Wynandermere, and the advowsons of the chapels of Wynandermere, Marieholm, and Gressemere.61

The new tenant at once incurred King Edward III.'s displeasure. His interests lay apparently in France, where he resided, being styled lord of Coucy62; and without waiting to do homage for his mother's English lands and receiving them formally from the king's hands (as was the feudal custom), he passed them over to his young son William. The king pardoned the offence, and ratified the grant,63 but he kept the youth, still a minor in 1339, about his person,64 and William's short life seems to have been spent in service under the English banner.65

The family of de Gynes had a difficult part to play during the wars that followed upon Edward's claim to the throne of France. Their hereditary instincts carried them naturally into the opposite camp, and they lost their English possessions in consequence. On William's death in 1343 the king – while he seems to have acknowledged the claim of his brother Ingelram as his heir,66 kept the heritage in his own hands. Moreover, he declared such lands as were held by Robert de Gynes, a son of Christiana, who was a cleric and Dean of Glasgow, to be forfeited, because of Robert's adherence to his enemy,67 and for the same reason lands at Thornton in Lonsdale held by Ingelram, son of Ingelram and grandson of Christiana, were likewise forfeited.68

The king presently used the escheated heritage to reward a knight who had served him well in the Scottish wars. John de Coupland had had the courage and address to secure Robert Bruce as prisoner at the battle of Durham; and Edward in 1347 granted to him and his wife for their joint lives the Lindesey Fee which was the inheritance of Ingelram. He excepted, however, from the grant (along with the park and woodlands about Windermere) the knight's fees and advowsons of churches belonging to the same.69

The fortunes of war brought Ingelram, lord of Coucy, and son of Ingelram, William's brother, as hostage for John, king of France, to the court of Edward. There he gained by his handsome person and knightly grace the favour of the king, who granted him the lands of Westmorland which had belonged to his great-grandmother Christiana, created him Earl of Bedford, and gave him in 1365 his daughter Isabella in marriage. Ingelram for some time satisfied his martial instincts by fighting in the wars of Italy and Alsace; but on the renewal of the struggle between England and France, followed by the death of his father-in-law in 1377, his scruples were at an end. He renounced his allegiance to England, haughtily returned the badge of the Order of the Garter, and joined the side of Charles II.70

The Lindesey Fee was once more forfeited to the Crown. Richard II. granted it, however, to Phillipa, daughter of Ingelram and Isabella, and to her husband Robert de Vere, earl of Oxford (1382); and when the latter was outlawed by Parliament in 1388 it was confirmed to her.71 After her death (1411) she was declared to have been seised of the advowson of the chapel of Grismere, taxed at £10, and that of Wynandermere, taxed at 100s.72

Phillipa had no children. Henry IV. now granted the Fee to his son, John, created duke of Bedford and earl of Kendal. He died in 1435. His property in the barony of Kendal included the "advowsons of Wynandermere and of Gressemere, each of which is worth 20 li yearly."73

The Duke of Bedford's widow, Jaquetta of Luxemburg, received the third part of the Fee as her dower, with the advowson "of the church in Gresmere." She married Richard Woodville, created earl Rivers. After her death she is said (1473) to have possessed "the advowson or nomination of the church or chapel of Gressemere," though in 1439 she had allowed her privilege to lapse.74

The Fee was next granted by Henry VI. (who inherited it as heir to his uncle John) to John Beaufort, duke of Somerset.75 The duke's daughter Margaret – afterwards countess of Richmond – came into possession of it at his death.76 After a lapse, when Yorkists sat on the throne, and Sir William Parr of Kendal held it, the Fee (now including the advowson of Grasmere) returned to Margaret and passed to her grandson Henry VIII. He sold the advowson and patronage of Grasmere. Its subsequent history will be given later.

Such was the illustrious line of our church's early patrons – some of them the most striking figures in a chivalrous age. But it is not to be supposed that they knew much of the little parish hidden amongst the mountains. When the rectorate fell vacant, they would grant the post to some suppliant clerk or priest, who would carry their nomination to the higher ecclesiastical authorities. The right to nominate often fell into the king's hands, through minority of the heir, confiscation, or inheritance. For instance, the king appointed to the rectory of Windermere in 1282, in 1377 and in 1388. Edward III. nominated Edmund de Ursewyk to "Gressemer" in 1349; and Henry IV. did the same for Walter Hoton in 1401.

MONASTIC CONTROL

Our church of Grasmere was not left to the control of parson and manorial lord like other tithe-yielding parishes, it was snapped up by a big monastery. The abbeys that had sprung up all over England in post-Norman times were of a very different order from the simple religious communities of Anglo-Saxon times; and before long it became a question as to how they were to be maintained on the splendid lines of their foundation. By the reign of Henry I. they had begun to appropriate rectories, and in 1212 the parish church of Crosthwaite was given over to the control of Fountains Abbey in Yorkshire, which carried off all the profits of the tithes, merely restoring £5 a year to the rector, who was elected by its chapter.77 St. Mary's Abbey had been founded in York city in 1088, and its chapter found it necessary by the end of the thirteenth century to look round the great church province of Richmondshire to see if there were no revenues which might by royal favour be appropriated.

In December, 1301, Edward I. despatched a writ to the sheriff of Westmorland, bidding him inquire of true and lawful men whether it would be to the damage of the Crown or others if the abbey of St. Mary of York were allowed to appropriate the church of Kirkeby in Kendale with its chapels and appurtenances.

The inquisition was held, be it noted, not at Kendal but at Appleby, where a sworn jury declared the appropriation would damage no one. An explicit statement was added which concerns us. "The chapels of the said church, to wit the chapels of Gresmer and Winandermere are in the patronage of Lord Ingram de Gynes and Christian his wife, by reason of the inheritance of the said Christian, and they hold of the king in chief… And the chapel of Gresmer is worth yearly 20 li."78

Accordingly a license was granted by Edward I., under date February 23rd, 1302, for the Abbot and Convent of St. Mary's, York, "towards the relief of their impoverished condition," to appropriate the "church of Kirkeby in Kendale, which is of their own patronage, in the diocese of York, and consists of two portions, on condition that they appropriate none of its chapels, if there are any."79

The appropriation took effect; and moreover the Abbey succeeded in gaining jurisdiction over the "chapels" of Windermere and Grasmere. The nomination of the rector indeed remained in the hands of the lord of the Fee, but it was passed on to the chapter of the Abbey for confirmation, before being finally ratified by the Archdeacon of Richmondshire. Thus three august authorities had to bestir themselves, when a fresh parson was needed for our parish; and in 1349 King Edward III., the Abbot of St. Mary and Archdeacon Henry de Walton were all concerned in the business.80 No doubt the monks seized the right to nominate whenever they could, and in 1439 George Plompton was named by them before his admission by the archdeacon.81

This change was not put into effect, however, without fierce opposition in the district. In 1309 an appeal went up to the king from the Abbot of St. Mary, who styled himself "parson of the church of Kirkeby in Kendale," wherein he stated that when his servants had gone to carry in the tithe corn and hay, they had been assaulted by Walter de Strykeland and others; and moreover that Roger, the vicar and the other chaplains and clerks appointed to celebrate divine service in that church, hindered them in the discharge of the same, trampled down and consumed his corn and hay, and took away the horses from his waggons and impounded them. Whereupon three justices were appointed to adjudicate upon the case.82

From this it would be seen that the local clergy were as bitterly opposed to the monastic rule as the gentry and the people. Sir Walter de Strickland with armed servants at his command headed the opposition. His lands at Sizergh lay to the south of the town of Kendal and he refused to the men of the monastery right of way across them for the collection of the tithes of corn, which was always made while the stooks stood upright in the field. After much wrangling, for no abbot was ever known to withdraw a claim, articles of agreement were made out between them, which reiterated the statement that the church of Kirkby Kendal was "canonically possessed in proper use" by the monastery.83 However, the convent found it easier to let the tithes to the opponent, rather than to wrestle with an obstructionist policy; and in 1334 Sir Walter is found agreeing to furnish to the monastic granary now established at Kirkby Kendal three good measures of oatmeal for the tithe of the sheaves of Sigredhergh, sold to him by the abbot and convent.84

But the people were not appeased, and when in 1344 the archbishop made a visitation, opportunity was taken to lay before him, in the name of "the common right," complaints against the monopoly of funds by the convent, as the following document shows: —

Release of the Abbot and Convent of the Monastery of St. Mary, York, concerning their churches, pensions, and portionsIn the name of God, Amen, Since we, William, by divine permission Archbishop of York, … in our progress of visitation which we have lately performed in and of our diocese … have found that the religious men the Abbot and Convent of the monastery of St. Mary, against the common right detain the parish churches and chapels, portions, pensions, and parochial tithes underwritten, namely, … the annual pensions in the parts of Richmond: of the church of Richmond 100s. and 20 lbs of wax, … of the vicarage of Kirkby Kendall £4, of the churches of Gresmere and Winandermers 5 marks… We have commanded the said abbot and convent … to show their rights and titles before us and have caused them to be called, … and we … having considered the rights and good faith of the said religious men … release the said abbot and convent … as canonical possessors of the said churches, chapels, portions, pensions (&c)… Dated at Cawood, on the 20th day of the month of August in the year of our Lord MCCCXLIIIJ, and in the third year of our pontificate.85

The appeal had been made in vain. Yet opposition could not have ceased, as the case was finally carried to Rome. In 1396 a confirmation of the abbey's possessions (including the chapels of Gresmere and Wynandremere, worth 5 marks each) was made by the Pope, on petition by the abbey, according to letters patent of Thomas Arundel, late archbishop of York, dated November, 1392.

THE CLERGY

Though not successful, Sir Walter de Strickland's opposition had done some good, but for exactly 200 years longer did the monastery by the walls of the city of York hold sway over the church of Grasmere. In what degree its influence was felt in the mountain parish cannot be told, or what it gave in return for the pension it abstracted. It may have assisted in the rebuilding of the edifice, lending aid by monastic skill in architecture. Probably it supervised the worship in the church, and improved the ritual, passing on to the village priest the tradition of its own richly furnished sanctuary. Signs were not wanting at the Reformation that the district had been ecclesiastically well served.

It has been seen that the parson of the parish was a pluralist and a non-resident as early as 1254; and so were those of his successors of whom we have evidence. The glimpses obtained through scant record disclose the tithe-taking rector of the valley as a figure distinguished by education, if not by family, and known to the lofty in station. He is termed "Master," and bears the suffix "clerk"; while "Sir" is reserved for the curate, his deputy, who has not graduated at either university.86 He was skilled in law more than in theology. He may have served an apprenticeship in the great office of the Chancery; sometimes men of his position are termed "king's clerk."87 He was not an idle man, and was often employed in secular business by the lord of the Fee. It may have been in the collection of the lady's dues – for the heiress Christiana de Lindesay, had married Ingelram de Gynes, of Coucy in France, in 1283 – that the parson of Grasmere suffered an assault (1290) at Leghton Gynes (later Leighton Conyers). It is certain that when Robert de Gynes, one of the sons of Christiana, and possessed of some of her lands about Casterton and Levens, went "beyond the seas" in 1334, he empowered Oliver de Welle, parson of Grasmere, to act with Thomas de Bethum as his attorney. Oliver de Welle had a footing in our valleys besides his parsonage, for he is stated to have held, under the lord William de Coucy, deceased, "a certain place called Little Langedon in Stirkland Ketle," which was then (1352) in the custody of the executor of his will, John de Crofte.88

Edmund de Ursewyk, "king's clerk," whom the king nominated to Grasmere in 1349 – the young lord William de Coucy being dead – doubtless came of a Furness family, and may have been related to Adam de Ursewyk who held land for his life in the barony, by grant of the elder William,89 as well as the office of chief forester of the park at Troutbeck.90

"Magister George Plompton" was another learned cleric of good family, being the son of Sir William Plumpton of Plumpton, knight. He was a bachelor-at-law, and was ordained sub-deacon in 1417. It was in 1438-9 that he was nominated to the rectory of Grasmere, by the Chapter of St. Mary's, and some years after he acquired that of Bingham in Nottinghamshire. This he resigned (and doubtless Grasmere also) in two or three years' time, owing to age and infirmities. He retired to Bolton Abbey, and in 1459 obtained leave from the Archbishop of York to have service celebrated for himself and his servants within the walls of the monastery – a permit which gives a picture of affluent peace and piety in a few words.91

Master Hugh Ashton, parson, acted as Receiver-general for the lands of the Countess of Richmond (the Lindesay Fee) in 1505-6.92 On his resignation in 1511, Henry VIII. exercised his right as inheritor of the Fee, and nominated John Frost to the rectory; the abbot and convent presenting in due form. This happened again in 1525, when William Holgill was appointed.93

Of other rectors of the post-Reformation period we know little or nothing. Richard, "clericus," was taxed in 1332 on goods worth £4, a sum higher by £1 than any land-holding parishioner in the three townships.94

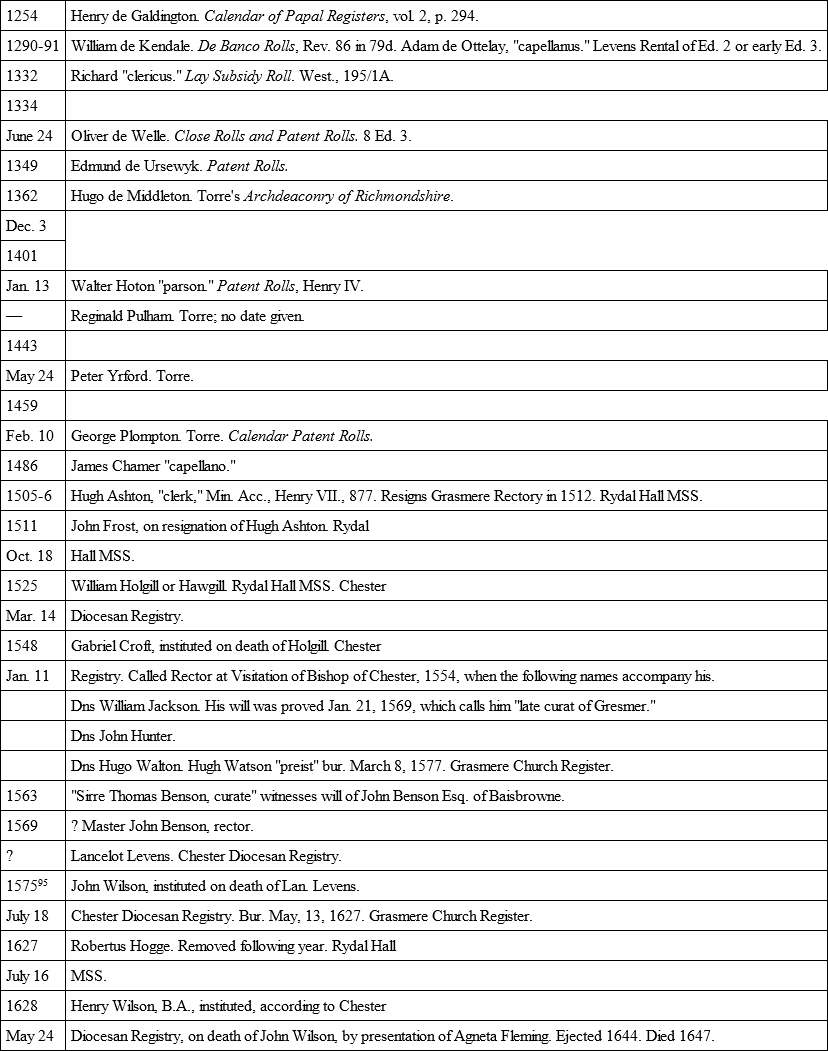

LIST OF RECTORS AND CURATES

95 1575 – March 20. James Dugdall, "Clericus" witnesses Indenture between Wil. Fleming of Rydal and his miller.

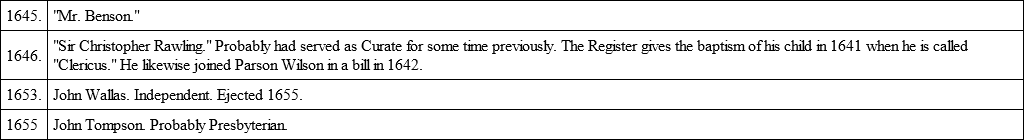

CLERGY DOING DUTY DURING THE COMMONWEALTH

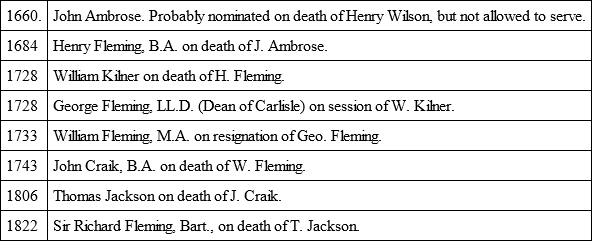

RECTORS AFTER RESTORATION

The curates who officiated under the rectors were a different class of men. Constantly resident, and seemingly holding the post for life, they belonged as a rule to the district – even it might be, to the township – as did William Jackson, who died 1569. A sharp boy, son of a statesman, might attract the notice of the parson, or of the visiting brother from St. Mary's Abbey. After serving an apprenticeship, as attendant or acolyte within the church, he might be passed on from the curate's tuition – for the latter almost always taught school – to Kendal or even to the abbey at York. On being admitted into the order of priesthood, he would return to his native place (should the post be vacant) and minister week by week to the spiritual needs of his fellows and his kinsfolk. Sometimes he even took up land to farm. Adam de Ottelay, "chaplain," is set down in an undated rental of the early fourteenth century, as joining in tenure with John "del bancke."96

The "chaplain" James Chamer, who witnessed a Grasmere deed in 1486, was probably the curate there.97 It must be remembered, however, that the three townships appear to have been, from an early (but unknown) date, furnished with resident curates, acting under rector and abbot. Little Langdale too, if tradition be correct, had its religious needs supplied by a chapel. It is possible, indeed, that this may have been served through the priory of Conishead in Furness, to which William de Lancaster III. – the last baron to rule Kendal as a whole, who died 1246 – granted a settlement or grange at Baisbrowne and Elterwater, which was later called a manor. This grange lay within Grasmere parish, as does the field below Bield, where tradition asserts the chapel to have stood. The first express mention of a chapel at Ambleside (within the township of Rydal and Loughrigg) is found in a document of Mr. G. Browne, dated 1584. But in the rental of 1505-6, William Wall, "chaplain," is entered as holding in Ambleside one third of the "pasture of Brigges." There is little doubt, therefore, that he was resident in the town, and uniting husbandry with his clerical office. Of a chapel in Great or Mickle Langdale the first evidence that occurs (after the strong presumptive evidence of the four priests serving the parish to be given immediately) is the indenture of 1571, which expressly mentions it.

The Start of the ReformationThe revolution which Henry VIII. brought about in the ecclesiastical world of England shook our parish, as the rest of England. Not content with the suppression and spoliation of the lesser monasteries, he turned to the greater ones, whose riches in gold and jewels, in land and revenue, excited his cupidity. Remote Grasmere even, by diversion of the pension she had dutifully paid her church superior, might supply something to the royal pocket! So the new supreme Head of the Church is found in 1543, bartering what he could to two of those job-brokers of ecclesiastical property, who were so evil a feature of the Reformation. The parchment at Rydal Hall runs thus: —

A Breuiate of the Kings Grant of Gersmire

Advowson to Bell & Broksbye in 35to Hen. 8

Be it remembered that in the charter of our most illustrious lord Henry the Eight, by the grace of God king of England, France, and Ireland, defender of the faith, and on earth supreme head of the English and Irish church, made to John Bell and Robert Brokelsby within named, among other things it is thus contained: —

The king to all to whom, &c. greeting. We do also give, for the consideration aforesaid, and of our certain knowledge and mere motion for us, our heirs and successors, do grant to the aforesaid John Bell and Robert Brokelsbye, the advowson, donation, denomination, presentation, free disposition, and right of patronage of the Rectory of Gresmere in our county of Westmorland, which, as parcel of the possessions and revenues of the late Monastery of St. Mary near the wall of the City of York, or otherwise or in any other manner or by any reason whatsoever, has or have fallen, or may fall, into our hands. Witness the king at Walden the twenty-first day of October in the thirty-fifth year of our reign.