полная версия

полная версияThe Church of Grasmere: A History

These places, it is true, had advantages over Grasmere. Kendal was in contact with the great world and with the heads of the church, who visited it regularly. It had, besides, access to freestone. Windermere, like Hawkshead, had to let the intractable slate of the neighbouring mountains suffice for the main structure: hence the great piers without capitals and the plaster finish of their interiors. But Windermere had an advantage in its nearness to Kendal; and Hawkshead in its association with the abbey of Furness, which was easily accessible from there. Grasmere, on the other hand, was probably ignorant of the beauties of the Abbey Church of St. Mary's at York, to which it was attached. The church was practically shut up within the remotest chamber of the mountains, and could only be reached by 17 miles of bad road from Kendal, over which no wheels could travel. But with no freestone near, with only the hard mountain slate to rive, or the boulders of the beck to gather; without traditional skill and with very little hard cash, our builders of Grasmere proceeded – when need came – to alter and enlarge their House of God by such simple methods as house and barn "raising" had made familiar to them. Thus we read the story of the structure as it stands at present, and see that the builders had clearly little help from the outer world. We see, too, that this structure was an alteration of an earlier one; which was not itself the first, for the first stone fane probably replaced a wooden one, either here or on Kirk How. It was doubtless of that simple oblong form, without chancel or tower, which was technically known as a chapel,124 and of which specimens have remained among the mountains to this day. But an ecclesia parochia, possessed of daughter chapels, could not be permitted by the higher powers – whether of church or manor – to retain so lowly a form. The manorial lords may have interested themselves in its reconstruction, though there is no evidence of the fact. In any case, it is likely that the Abbey of St. Mary would take the necessary steps to bring it up to the requirements of its position, and of the worship to be conducted within its walls. The visiting brother would carry accounts of the remote little church to York; and a monk skilled in architecture could be brought over to plan a new building, and to direct its construction. The customary model for a small parochial church would be adopted, which allowed a chancel for priests officiating at the mass; then a nave without aisles for the worshippers, lighted by narrow windows – for before glazing was possible the opening had to be guarded from weather by wooden shutters – and to the west a tower, in which to hang the bells that should call the parishioners from far.

Such doubtless was the existing church in its first state, and of it there may remain the tower, the porch, the south wall, and one window. There are indications that before its enlargement it was more ornate then now. Freestone was used, though sparingly, to emphasize the chief architectural points. The opening into the tower, piercing four feet of solid wall, has a moulding of freestone (now battered away) to mark the spring of its slightly-pointed arch; while a string-moulding is discernible in the north wall of the nave, which may once have accentuated the window heads. The windows – if we may suppose the one left between porch and tower to be a relic of the original set125– were simple openings finished by an "ogee" arch. The font may be as old as the window, if not older. Its mouldings, which originally followed the rim and divided the bowl into a hexagon, are almost obliterated; and though no doubt it suffered during the Commonwealth, when it was degraded from its sacred use, the damage may not be wholly due to that cause. The freestone used in the building was unfortunately friable, and must have suffered at every alteration – such as the piercing of the north wall by arches, and the building up of the tower-arch for a vestry. It could not be replaced by the remodellers; and they seem to have intentionally chipped and levelled it, and then freely whitewashed it over, with a general view to tidiness. They even went beyond this; for when the east wall was reconstructed in 1851, a stone carved with the likeness of a face was found built into it. This is now in the Kendal Museum. The piscina, too, now refixed (and, unfortunately, redressed), was found, covered with plaster, lower down in the same wall.

The worn, maltreated freestone might, if we knew its origin, tell something of the tale of the building. A well-squared yellow block, recently laid bare in the porch, is certainly not the red sandstone of Furness.

Now should the age of the fabric, decorated thus simply though judiciously, be questioned, it must be owned that there is nothing to indicate its being older than the fourteenth century. It is true that a western tower with no entrance from outside was a feature of many Saxon churches, but such towers continued to be built for parish churches until a late date. The rough masonry of the Grasmere tower is due to the material; and the massive boulders used in the foundation were no doubt gathered from the beck, whose proximity must have been highly convenient for builders who were poorly equipped for the quarrying of their slate rock. The "ogee" or trefoiled arch was a development of the Decorated style of architecture, which evolved the form from the elaborate traceries of its windows.126 The Decorated style is roughly computated as lasting from the open to the close of the fourteenth century, and the period of its use coincides fairly with the time when our church fell under the influence of the monastery.

A church of primitive size would be sufficient for the folk of the three townships, while they lived in scattered homesteads and were all bent upon husbandry, with short intervals of warfare with the Scots. But it would become too small for a growing population that throve in times of peace upon the wool trade.127 With walk-mills in the valleys, and families growing rich as clothiers, some extension of the church would be necessary; and this extension seems to have been started in a fashion strangely simple. Leaving the walls of the edifice intact with its roof, a space almost equal – for it is but one yard narrower – was marked off on the northern side, enclosed by walls and roofed over. The intervening wall could not be removed, because the builders were incapable of spanning the double space by a single roof. It was therefore left to sustain the timbers of the two roofs, and through its thickness (over three feet) spaces were broken in the form of simple arches. Thus – though one is called an aisle – two naves were practically formed, separated by the pierced wall. The date of this enlargement is uncertain. If we place it in the era of the prosperity of the townships from the cloth trade, it could have been done no earlier than the reign of Henry the Seventh, and no later than the early days of Elizabeth; while a supposition that it was not taken in hand until the dissolution of the monastery had thrown the men of the three townships on their resources is strengthened by the character of the work.

How long the enlarged church remained under a double roof cannot be said. Trouble would be sure to come from the long, deep valley, where snow would lodge and drip slowly inside. Clearly there was urgent need for action and radical alteration when the powerful Mr. John Benson, of Baisbrowne, made his will in 1562. A clause of this runs: "Also I giue and bequeath towardes the Reparacions of the church of gresmyre XXs so that the Roofe be taken down and maide oop againe."

But how to construct a single roof over the double space? This insoluble problem (to them) was met by the village genius in a singular manner. The arched midwall was not abolished. It was carried higher by means of a second tier of arches whose columns rest strangely on the crowns of the lower. These upper openings permit the principal timbers to rest in their old position, while the higher timbers are supported by the abruptly ending wall. Thus a single pitched roof outside is attained, sustained by a double framework within. The result is unique, and remains as a monument of the courage, resource, and devotion to their church of our mountain dalesmen.

[Since this chapter was written the stone face – p. 104 – has been returned by Kendal to Grasmere. – Ed.]

THE FURNITURE

Of early furniture there is, of course, no trace within the church. All the accessories of the ritual of the mass, whether in metal, wood, or textile, as well as such as would be required for processions on Rogation Days, were swept away at the Reformation. A reminder of these processions may perhaps be found in the field at the meeting of the roads near the present cemetery, which goes by the name of Great Cross, for here, doubtless, a Station of the Cross stood where the priest and the moving throng would halt and turn. Another field is named Little Cross.

One upright piece of oak, roughly cut with the date 1635, remains to show us the style of the old benches – or forms as they were called – which filled the space above the earthen floor. The bench itself, to judge by the aperture left in this end-piece, would appear to have been no more than six inches wide, and almost as thick; the bench-end, which was further steadied by a slighter bar below, was sunk into the ground.

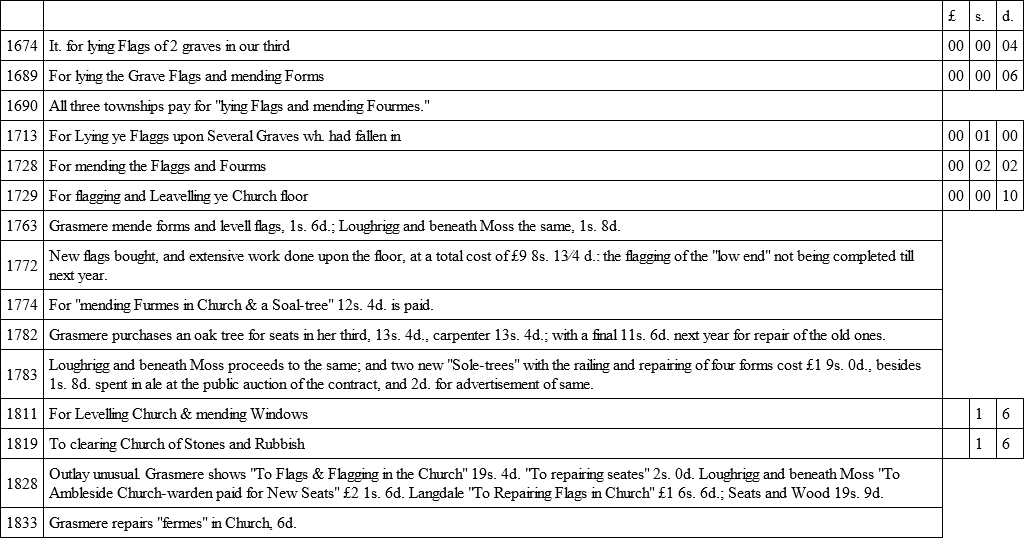

These benches could not have been fixed with any permanence, for the earthen floor was often broken up for the burial of parishioners. The custom of burial inside the church was a favourite one, and was continued down to the nineteenth century. While the choir was reserved for the knight or gentleman (and of the former there were none within the parish) and for the priest, the statesman was buried in the nave or aisle; and only the landless man or cottar would be laid in the garth outside. Frequently in wills the testator expressed his wish to be buried as near as possible to a deceased relative, or the place where he had worshipped. He was in any case buried within the limits of his township's division in the church. In 1563 Mr. John Benson, of Baisbrowne, who was a freeholder and probably a cloth merchant, desired to be buried "in the queare in the parish church of gresmire as neare where my wife lyethe as convenientlye may be." After the Fleming family of Rydal and Coniston became possessed of the advowson, they were many of them – beginning with William the purchaser in 1600 – buried within the choir; though no monument or tablet exists prior to the one commemorating Sir Daniel's father, 1653. The tithe-paper shows the rate of payment for interment in the higher or lower choir. Besides fees paid to the officials of the church, the townships, through their individual wardens, took payment for all "ground broken," as the phrase went, within their division, and the receipts from this source appear regularly in their accounts. The usual fee for an adult was 3s. 4d. (a quarter mark), and out of this 2d. had to be paid by the wardens for laying the flag. Less was charged for children, while women who died in childbirth were buried for nothing but the actual cost of the flag-laying. Under the year 1693, when seven parishioners were laid within the church soil, we read "& more for the burying of two Women yt. dyed in Childbed in the Church00li 00s 04d." There were seven burials in 1723, five in 1732, five in 1766, and four in 1773. As late as 1821 Rydal and Loughrigg buried one inhabitant in the church, and Langdale three. It is singular that the Grasmere township discontinued the custom before the two others, for no interment took place in her division after 1797.

The following extracts from the wardens' accounts show how frequently the floor of the church was disturbed and levelled: —

The soil beneath the church is thus literally sown with bones, and the wonder is that room could be found for so many. But in this connection it must be remembered that the practice of burying without coffins was the usual one until a comparatively recent period.

No wonder that plague broke out again and again, that the fragrant rush was needed for other purpose than warmth, and that fires within the church could not have been tolerated.

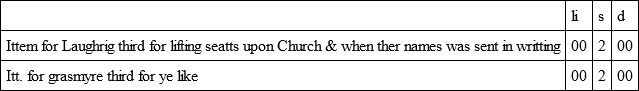

The custom concerning these forms or ferms, as locally pronounced, was rigid. Every man had a right, as townsman or member of a vill, to a recognized seat within the church, which was obtained through the officials of his township. This seat was, of course, within the division of his township. The women sat apart from the men, and even the maids from the old wives. So tenaciously was the hereditary seat clung to, that reference to it may occasionally be met with in a will.128

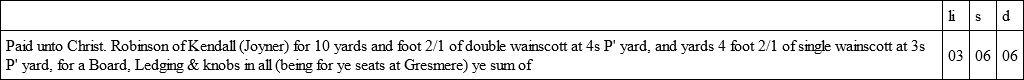

Some serious alteration in the allotment of seats was probably made in 1676, judging from these entries in the wardens' accounts.

The Squire of Rydal, as soon as the Restoration permitted it, set to work to furnish that part of the church in which he worshipped suitably to the honour and dignity of his family. The family seats had before his time long stood vacant, even if they had been ever regularly used. His predecessor, John, as an avowed Roman Catholic, had preferred to pay heavy fines rather than obey the law in the matter of attendance at the Communion of the parish church; and there is little doubt that the mass was celebrated in private for him at Rydal Hall. John's mother, Dame Agnes, may have attended during her widowhood; but her husband William, the purchaser of the tithes and patronage, must – always supposing him to be a good Protestant – have attended more frequently at Coniston.

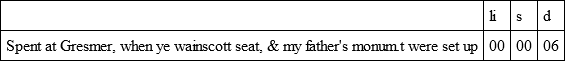

But Squire Daniel was a pillar of the church as well as of the State in his neighbourhood, and his accommodation within the building was framed in view of the fact. The following entry occurs in his account book, under July 13th, 1663. The monument referred to is doubtless the brass tablet we now see in the chancel, and it appears to have waited for its fixing for ten years after its purchase in London: —

And two days later the bill for the seat was paid. It is not very intelligible, but reads thus: —

No doubt this is the fine old pew which still stands between the pulpit and the priest's door of the chancel. In it, for nearly forty years, the squire worshipped, with his growing family about him. The regularity of his attendance is shown by his account book, where every collection is entered; and in spite of his frequent ridings on public and private business, he never but once (till the close of the book in 1688) missed the four yearly communions in his parish church. On that occasion, when Easter Day, 1682, was spent at Hutton, he attended a service at Grasmere on the previous Good Friday (held possibly by his order), at which his Easter offering was given.

Given this day (being Good-Fryday) at ye Offertory in Gresmere Church for myselfe 5s., for Will, Alice, Dan, Barbara & Mary 5s.

The sums given were invariable: 5s. for himself, 2s. 6d. for his wife (while she lived), and 1s. for each child.129

It was in 1675 that the sad necessity rose of putting up a monument to his excellent wife. The brass was apparently cut in London, for he sent to his Uncle Newman there: —

3li 10s. 0d. towards ye paying for my late dear wifes Epitaphs engraving in brass.

Though 2s. 6d. more was paid afterwards.

Unto Rich. Washington of Kendall for amending of my late Dear Wifes Epitaph in brass.

Washington, who was entered in 1642 among the "Armerers Fremen and Hardwaremen" of Kendal, and was mayor of the city in 1685,130 was wholly entrusted with the next family brass; for we find that under date February 10th, 1682, he was paid "for ye Brass & the cutting of ye Epitaph for my Mother and Uncle Jo. Kirkby, £4 10s 0d which my brothers Roger & William are to pay me again." But this was for Coniston Church.

It was after the squire's second son, Henry, had become Rector of Grasmere, and by his encouragement, that the church was freshly beautified and "adorned." The entry of 1s. paid in 1662 to James Harrison for "makeing ye sentences w'in ye church" shows that something was at once attempted; for it was as imperative that a church should be "sentenced" as that the Royal Arms should be put up, or the Commandments or Lord's Prayer. All these were devices (expressly enjoined by the sovereign) for covering up the nakedness of the churches after they had been stripped by the Reformers of all objects of beauty and reverence, in roods, images of saints, tapestries, &c., &c.; for Elizabeth and many of her subjects had been horrified at the effect of changes that appeared to rob the churches of their sacred character.131 Frescoes on plaster had, of course, been used from early times as a means of teaching Holy Writ and Legend to the unlettered folk, and fragments of such pictures are still to be seen in Carlisle Cathedral. But at the Reformation, when plaster and paint were again resorted to, only the written word was permitted (with the exception of the Lion and Unicorn); and the wall-spaces of the churches became covered with texts and catechisms,132 which were surrounded or finished by "decent flourishes."133

In its turn the reformed style has disappeared, even in churches peculiarly suited to it, like those of the Lake District, where the rough unworkable slate is bound to be covered by a coat of plaster. During recent restorations, however, at both Windermere and Hawkshead the sentences were found under coats of whitewash, and they were in a truly conservative spirit painted in again. Grasmere, weary of "mending" the sentences and whitening round them, finally wiped them out in the last century, and substituted the ugly black boards painted with texts, which still hang between the archways. Fragments of the old sentences were descried when the walls were recently scraped and coloured.

It was in 1687 that a complete scheme of decoration was carried out within the church, and one James Addison, a favourite decorator in the district, was engaged for the purpose. The contract made with him is preserved in the churchwardens' book: —

Mr. Adison is to playster what is needfull & whiten all the Quire & Church except that within the insyde of the Arche of the steeple to paint the 1 °Coman's on the one syde of the Quire window & the beliefe & Lordes prayer on the other with 8 sentences & florishes in the Quire & 26 sentences in the Church with decent Florishes & the Kinges Armes well drawn & adorned.

Later on comes the copy of an agreement in later handwriting: —

March the 29th An'o Dom'i 1687.Mem'd. It was then agreed on by and between James Addison of Hornby in the County of Lancaster Painter on the one part and Mr. Henry Fleming of Grasmer the churchwardens and other Parishioners of the Parish aforesaid: That the said James Addison shall and will on this side the first day of August next after the date hereof sufficiently plaster wash with Lime and whiten all ye church of Grasmer aforesaid (except ye inside of the steeple) and well and decently to paint ye Tenne Commandm'ts, Lord's prayer and thirty Sentences at such places as are already agreed on together with the Kings Arms in proper colours and also to colour the pulpit a good green colour and also to flourish the Pillars and over all the Arches and doors well and sufficiently, the said Parson and Parishioners finding lime and hair onely. In consideration whereof the sd. Parson and Parishioners doe promise to pay him nine pounds Ten shillings when or so soon as the work shall be done.

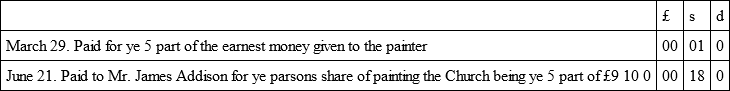

And be it likewise remembered the s'd Parson and Parishioners gave him 05s in earnest and that the Parson is to pay the fifth part of the nine pounds Ten shillings, the parishioners being at the whole charge of the lime and Hair.

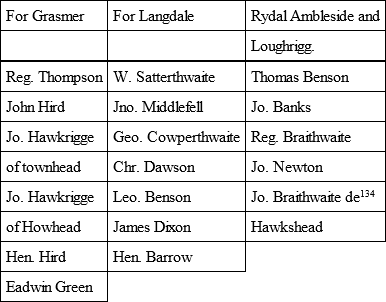

The names of the 18 Questmen

134 This is somewhat inexplicable unless the copyist, who has a late hand, has mistaken Howhead (in Ambleside) for Hawkshead. And the last figure in the account should be £1 18s.

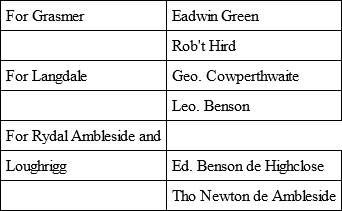

Church Wardens

Memorand. That to promote ye Painting of ye ch'h ye Parson did offer to pay according to ye proportion ye Quire did bear to ye whole ch'h to ye plastering washing w'h lime and painting of ye ten Command'ts Creed L'ds prayer and 30 sentences, tho' y'er had but been 4 or 5 Sentences in ye Quire before and now ye ten Comma'd'ts and Creed were to be painted on each side of the quire windows The Charge of all which was commuted at £8 0 0 and ye K'gs Arms and ye painting of ye pulpit at ye remainder. So that the quire appearing by measure to be a 5 part ye Parson was to pay £1 12s. 0d. but to be quit of the trouble of providing his proportion of lime and hair he did prefer to pay ye 5 part of the whole £9 10s. 0d. ye parish finding all lime and hair which was agreed to. Besides ye £9 10s. 0d. agreed to be paid there was 5s. 0d. given to the painter in earnest to have the work done well.

The contract included the painting of the pulpit of a cheerful green, as we read. It was a plain structure of wood, and the "Quission" bought for it in 1661, as well as the cloth then procured for the Communion Table, were doubtless worn out; for we learn from the church-wardens' Presentment for 1707 that these and some other points about the church had been found wanting by the higher church authorities. The paper runs: —

The defects found in our church for and at ye late Visitation, viz. The Floor of the Church-porch & Isles uneven Flagg'd; The South wall of the Inside fro' ye Bellfry unto ye East, dirty; A decent Reading-pew, Com'unio'-Table-cloth of Linen, & pulpet Cushio' wanting; A Table of degrees wanting, & a crackt Bell.

All these faults except two (viz. The Reading-pew & crackt Bell) are amended. The porch & Isles even Flagg'd. The Wall made white & clean, A decent Table-cloth, Pulpet-Cushion, & Table of degrees, procured.

A new Reading-pew is in making at present, & will shortly be perfected. & as for the Bell it was referr'd to Dr. Fleming's discerec'on to be amended & made tuneable; & he resolves in convenient time to call together & consult w'th the chief of his Parishion'rs to do it, & in w't time and manner, to the best Advantage."

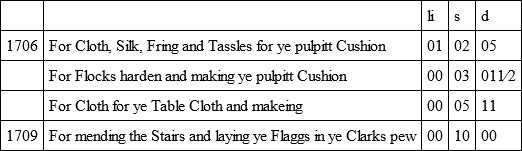

Accordingly we find entries of the expense incurred by a few of these requirements: —

Nothing is heard, however, of a new reading-pew, and in 1710 the old one was mended at a cost of 1s. 8d. The bells, as we shall see, had to wait.

Not until a hundred years later was a vestry thought of. In 1810 Thomas Ellis was paid 7s. for planning it, and George Dixon £12 2s. 1d. for its erection. It is said to have been made of wood, and simply partitioned off the north-west angle of the church. It was fitted with a "grate," that cost with carriage 19s.; and this being set on the side nearest to the pews, diffused what must have been but a gentle warmth through the edifice. It is the first heating apparatus that we hear of, and the expenses for charcoal and wood, with 3s. paid annually to the clerk for setting on the fire, were small. Tradition says that while George Walker lighted the vestry fire he rang the eight o'clock bell – a call to matins which had survived the Reformation, and the service then abolished.135

Time brought other improvements. The harmony of a church choir entailed its special expenses. In 1812 the ladies of Rydal Hall, widow and heiress of Sir Michael Fleming, provided "Psalmody" for Grasmere church at a cost of £2 2s., and for Langdale at £1 1s. Probably the price of this early tune-book was one guinea. A charge of 7s. 6d. appears in 1829 for a new pitch-pipe. A "singing school" was started, causing considerable expense in candles (12s. in 1844). Edward Wilson fitted the "singing pews" with drawers in 1851. There was apparently no instrumental music in the Grasmere choir, though there may have been in Langdale chapel to judge from an item of expense for violin strings.