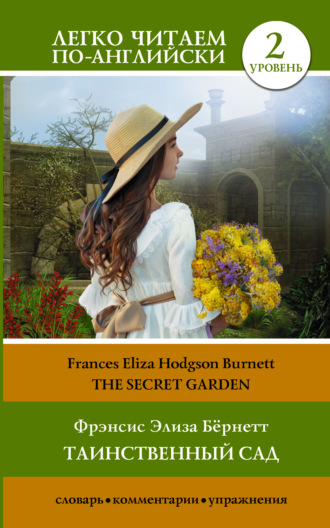

Полная версия

Таинственный сад / The secret garden

Your loving sister,

Martha Phoebe Sowerby.”

“We’ll put the money in the envelope and I’ll get the butcher’s boy to take it in his cart. He’s a great Dickon’s friend,” said Martha.

“How shall I get the things when Dickon buys them?” asked Mary.

“He’ll bring them to you himself.”

“Oh!” exclaimed Mary, “then I shall see him!”

“Do you want to see him?” asked Martha suddenly.

“Yes, I do. I never saw a boy foxes and crows loved. I want to see him very much.”

Martha stayed with her until tea-time, but they talked very little. Just before Martha went down-stairs for the tea-tray, Mary asked a question.

“Martha,” she said, “has the scullery-maid had the toothache again today?”

Martha certainly started slightly.

“Why do you ask?” she said.

“I opened the door and walked down the corridor. And I heard that crying again, just as we heard it the other night. There isn’t a wind today.”

“Eh!” said Martha restlessly. “There’s Mrs. Medlock’s bell.”

And Martha almost ran out of the room.

“It’s a very strange house,” said Mary drowsily and she fell asleep.

Chapter X

Dickon

Mary was beginning to like to be out of doors; she no longer hated the wind, but enjoyed it. She could run faster, and longer, and she could skip very well.

Mary was an odd, determined little person, and now she had something interesting. She was very much absorbed, indeed. She worked and dug and pulled up weeds steadily. It seemed to her like a game. Sometimes she stopped digging to look at the garden and try to imagine it with thousands of flowers.

“How long have you been here?” Ben Weatherstaff asked her one day.

“I think it’s about a month,” she answered.

“That’s just the beginning,” he said.

“Have you a garden of your own?” she asked.

“No. I’m a bachelor and lodge with Martin.”

“If you have one,” said Mary, “what will you plant?”

“Cabbages and potatoes an onions.”

“But what about a flower garden?” persisted Mary.

“Mostly roses.”

“Do you like roses?” she said.

“Well, yes, I do. The young lady was fond of them. She loved them like they were children-or robins. She kissed them. Ten years ago.”

“Where is she now?” asked Mary.

“Heaven,” he answered, and drove his spade deep into the soil.

“What happened to the roses?” Mary asked again.

“They were left to themselves[20]. Why do you care so much about roses?”

Mary was almost afraid to answer.

“I–I want to play that-that I have a garden of my own,” she stammered. “I-there is nothing for me to do. I have nothing-and no one.”

“Well,” said Ben Weatherstaff slowly, as he watched her, “that’s true.”

Mary went skipping slowly down the outside walk. The walk curved round the secret garden and ended at a gate which opened into a wood, in the park. Suddenly she heard a low, peculiar whistling sound.

It was a very strange thing indeed. A boy was sitting under a tree, playing on a rough wooden pipe. He was about twelve. He looked very clean and his nose turned up and his cheeks were as red as poppies. And on the trunk of the tree, a brown squirrel was clinging and watching him, and from behind a bush nearby a cock pheasant was delicately stretching his neck to peep out, and quite near him were two rabbits sitting up and sniffing with tremulous noses.

When he saw Mary he spoke to her,

“Don’t move. They are afraid.”

Mary remained motionless. He stopped playing his pipe and rose from the ground. The squirrel scampered back up into the branches of the tree, the pheasant withdrew its head and the rabbits began to hop away.

“I’m Dickon,” the boy said. “I know you’re Miss Mary.”

“Did you get Martha’s letter?” she asked.

He nodded his head.

“That’s why I’m here.”

He took something which was lying on the ground beside him.

“I’ve got the garden tools. A little spade and rake and a fork and hoe. Eh! They are good. There’s a trowel, too. And some seeds.”

“Will you show the seeds to me?” Mary said.

They sat down and he took a clumsy little brown paper package out of his coat pocket. He untied the string and inside there were many smaller packages with a picture of a flower on each one.

He stopped and turned his head quickly.

“Where’s that robin?” he said.

The chirp came from a thick holly bush.

“Aye,” said Dickon, “he’s calling someone. He says ‘Here I am. Look at me.’ There he is in the bush. Whose is he?”

“He’s Ben Weatherstaff’s, but I think he knows me a little,” answered Mary.

“Aye, he knows you,” said Dickon. “And he likes you. He’ll tell me all about you in a minute.”

He moved quite close to the bush with the slow movement. Then he made a sound almost like the robin’s own twitter. The robin listened a few seconds, intently, and then answered.

“He’s a friend of yours,” chuckled Dickon.

“Do you understand everything birds say?” said Mary.

“I think I do, and they think I do,” he said. “I’ve lived on the moor with them so long. I’ve watched them a lot. I think I’m one of them. Sometimes I think perhaps I’m a bird, or a fox, or a rabbit, or a squirrel, or even a beetle.”

He laughed and came back to the log and began to talk about the flower seeds. He told her how to plant them, and watch them, and feed and water them.

“Look,” he said suddenly. “I’ll plant them for you myself. Where is your garden?”

She turned red and then pale.

“I don’t know anything about boys,” she said slowly. “Can you keep a secret, if I tell you one? It’s a great secret.”

Dickon rubbed his hand over his head again, but he answered quite good-humoredly.

“I’m keeping secrets all the time,” he said. “Aye, I can keep secrets.”

“I’ve stolen a garden,” she said very fast. “It isn’t mine. It isn’t anybody’s. Nobody wants it, nobody cares for it, nobody ever goes into it. Perhaps everything is dead in it already; I don’t know.”

Dickon’s curious blue eyes grew rounder and rounder.

“Eh-h-h!” he said.

“I’ve nothing to do,” said Mary. “Nothing belongs to me. I found it myself and I got into it myself. I was only just like the robin.”

“Where is it?” asked Dickon.

Mary got up from the log at once.

“Come with me and I’ll show you,” she said.

She led him round the laurel path and to the walk where the ivy grew so thickly. Dickon followed her with a queer look on his face. He moved softly. When she stepped to the wall and lifted the hanging ivy he started. There was a door and Mary pushed it slowly open and they passed in together.

“It’s this,” she said. “It’s a secret garden, and I’m the only one in the world who wants it to be alive.”

Dickon looked round it, and round and round again.

“Eh!” he almost whispered, “it is a queer, pretty place! It’s like a dream.”

Chapter XI

Mary’s nest

“What a garden!” Dickon said, in a whisper.

“Did you know about it?” asked Mary.

Dickon nodded.

“Martha told me about it,” he answered.

He stopped and looked round at the lovely gray tangle about him, and his eyes looked happy.

“Eh! It will be the safest nesting place in England.”

Mary put her hand on his arm.

“Will there be roses?” she whispered. “Can you tell? Perhaps they were all dead.”

“Eh! No! Not all of them!” he answered. “Look here!”

He stepped over to the nearest tree with a curtain of tangled sprays and branches. He took a thick knife out of his pocket and opened one of its blades.

“I see dead wood here,” he said. “But this one is alive,” and he touched a shoot which looked green instead of hard, dry gray.

Mary touched it herself.

“That one?” she said. “Is that one quite alive?”

“It’s as alive as you or me,” he said.

“I’m glad it’s alive!” she cried out. “I want them all to be alive. Let us go round the garden and count how many alive ones there are.”

They went from tree to tree and from bush to bush. Dickon carried his knife in his hand and showed her things which she thought wonderful.

“These are dead,” he said, “but those are strong. See here!” and he pulled down a thick gray branch. He knelt and with his knife cut the branch through, not far above the earth.

“There!” he said exultantly. “I told you so. It’s alive. Look at it. There’s a big root here,” he stopped and lifted his face. “There will be a fountain of roses here this summer.”

They went from bush to bush and from tree to tree. He was very strong and clever with his knife and knew how to cut the dry and dead wood away. The spade, and hoe, and fork were very useful. He showed her how to use the fork while he dug about roots with the spade and stirred the earth. They were working industriously.

“Why!” he cried, pointing to the grass a few feet away. “Who did that there?”

It was one of Mary’s own little clearings.

“I did it,” said Mary.

“I thought that you didn’t know anything about gardening,” he exclaimed.

“I don’t,” she answered, “but they were so little, and the grass was so thick and strong. They had no room to breathe. So I made a place for them.”

Dickon went and knelt down by them, smiling.

“That was right,” he said. “They will grow now. They’re crocuses and snowdrops, and these here are narcissuses. A lot of work for such a little wench!”

“I’m growing stronger,” said Mary, “And when I dig I’m not tired at all. I like to smell the earth.”

“It’s good for you,” he said, nodding his head wisely. “When it’s raining I lie under a bush and listen to the soft swish of drops.”

“Do you never catch cold?” inquired Mary, gazing at him wonderingly.

“Not me,” he said, grinning. “I have never caught cold since I was born.”

He was working all the time he was talking and Mary was following him and helping him with her fork or the trowel.

“There’s a lot of work to do here!” he said.

“Will you come again and help me to do it?” Mary begged. “I can dig and pull up weeds, and do whatever you tell me. Oh! do come, Dickon!”

“I’ll come every day if you want, rain or shine,” he answered stoutly. “Eh! We’ll have a lot of fun.”

He began to walk about, looking up in the trees and at the walls and bushes with a thoughtful expression.

“It’s a secret garden,” he said, “right?”

“The door was locked and the key was buried,” said Mary. “No one could get in.”

“Yes,” he said. “It’s a queer place.”

Dickon laughed. Mary looked at him.

“Dickon,” she said. “You are as nice as Martha said you were. I like you. I never thought I could like five people.”

Dickon looked funny and delightful, Mary thought, with his round blue eyes and red cheeks.

“Only five people?” he said. “Who are the other four?”

“Your mother and Martha,” Mary said, “and the robin and Ben Weatherstaff.”

Dickon laughed again.

“I know you think I’m a queer lad,” he said, “but I think that you are a very queer lass.”

Then Mary did a strange thing. She leaned forward and asked him a question,

“Do you like me?”

“Eh!” he answered heartily, “I do. I like you, and so does the robin, I believe!”

“That’s two, then,” said Mary. “That’s two for me.”

And then they began to work harder than ever and more joyfully. Then Mary heard the big clock in the courtyard strike the hour of her midday dinner.

“I shall go,” she said mournfully. “And you will go too, won’t you?”

Dickon grinned.

“My dinner is with me,” he said. “Mother always gives me a bit of something in my pocket.”

He picked up his coat from the grass and brought out of a pocket a lumpy little bundle. It held two thick pieces of bread with a slice of bacon.”

Mary thought it looked a queer dinner. She went slowly to the door in the wall and then she stopped and went back.

“Whatever happens, you-you never will tell?” she said.

He smiled encouragingly.

“Not me,” he said.

Chapter XII

A bit of Earth

Mary ran fast and reached her room. Her dinner was waiting on the table, and Martha was waiting near it.

“You’re late,” she said. “Where have you been?”

“I’ve seen Dickon!” said Mary. “I’ve seen Dickon!”

“Yes,” said Martha exultantly. “How do you like him?”

“I think-I think he’s beautiful!” said Mary.

Martha looked pleased.

Mary ate her dinner as quickly as she could. When she rose from the table she was going to run to her room to put on her hat again, but Martha stopped her.

“I’ve got something to tell you,” she said. “Mr. Craven came back and I think he wants to see you.”

“Oh!” Mary said. “Why! Why! He didn’t want to see me when I came.”

“Well,” explained Martha, “I don’t know about it, but he wants to see you before he goes away again, tomorrow.”

“Oh!” cried Mary, “is he going away tomorrow? I am so glad!”

“He’s going for a long time. He won’t come back till autumn or winter. He’s going to travel abroad.”

“Oh! I’m so glad-so glad!” said Mary. “When do you think he will want to see…”

She did not finish the sentence, because the door opened, and Mrs. Medlock walked in. She looked nervous and excited.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Примечания

1

at all – совсем

2

she was kept out of the way – её держали на расстоянии

3

feeling very cross – в дурном настроении

4

broke out among your servants – дошла до ваших слуг

5

made faces – кривлялся

6

boarding-school – школа-пансион

7

their daughter’s guardian – опекун их дочери

8

Don’t you care? – Неужели тебе всё равно?

9

sour young man – желчный юноша

10

was raking out the cinders – выгребала золу

11

slapped her in the face – давала ей пощёчины

12

out of kindness – по доброте душевной

13

turned down the walk – побрела по тропинке

14

it’s not to be talked about – это не тема для разговоров

15

scullery-maid – судомойка

16

just the same – всё равно

17

held out her hand – пожала ей руку

18

Upon my word! – Ну и ну!

19

There now! – Вот как!

20

They were left to themselves. – Их забросили.