Полная версия

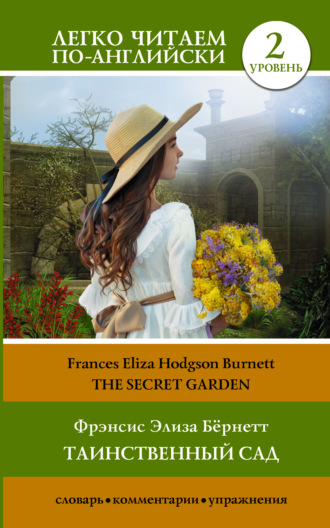

Таинственный сад / The secret garden

Фрэнсис-Элиза Ходжсон Бёрнетт

Таинственный сад / The secret garden

© Матвеев С. А.

© ООО «Издательство АСТ», 2021

Frances Hodgson Burnett

The Secret Garden

Chapter I

There is no one left

When Mary Lennox was sent to Misselthwaite Manor to live with her uncle everybody said she was a very disagreeable-looking child. It was true. She had a little thin face and a little thin body, thin light hair and a sour expression. Her hair was yellow, and her face was yellow because she was born in India and was always ill.

Her father held a position under the English Government and was always busy and ill himself. Her mother was a great beauty who cared only to go to parties and amuse herself. She did not want a little girl at all[1]. When Mary was born she handed her over to the care of an Indian nurse. So when she was a sickly, fretful, ugly little baby she was kept out of the way[2]. And when she became a sickly, fretful, toddling girl she was kept out of the way also. She saw the dark faces of her nurse and the other native servants. They always obeyed her. So by the time the girl was six years old she was very tyrannical and selfish.

The young English governess who came to teach her to read and write disliked her so much that she left in three months. When other governesses came they always went away even sooner. So Mary learned letters herself.

One frightfully hot morning, when she was about nine years old, she awakened feeling very cross[3]. She became crosser when she saw that the servant who stood by her bedside was not her Ayah.

“Why did you come?” she said to the strange woman. “I will not let you stay. Send my Ayah to me.”

The woman looked frightened. She only stammered that the Ayah could not come. Mary kicked her. The servant looked only more frightened and repeated that it was not possible for the Ayah to come.

There was something mysterious in the air that morning. The servants hurried about with ashy and scared faces. But no one told the girl anything and her Ayah did not come. She was actually left alone. At last she wandered out into the garden and began to play by herself under a tree near the veranda. She was growing more and more angry. She was muttering to herself,

“Pig! Pig! Daughter of Pigs!” she said, because to call a native a pig is the worst insult of all.

She was grinding her teeth and saying this over and over again when she saw her mother. Her mother came out on the veranda with someone. She was with a fair young man and they stood talking together in low strange voices. Mary knew the fair young man who looked like a boy. He was a very young officer from England. The child stared at him, but she stared most at her mother. She always did this when she had a chance to see her. Her mother was a tall, slim, pretty person and wore lovely clothes. Her hair was like curly silk and she had a delicate little nose and large laughing eyes. All her clothes were thin and floating.

But this morning, her eyes were not laughing at all. They were large and scared and lifted imploringly to the fair boy officer’s face.

“Is it so very bad? Oh, is it?” she said.

“Awfully,” the young man answered in a trembling voice. “Awfully, Mrs. Lennox. Why didn’t you go to the hills?”

Mother wrung her hands.

“Oh, I know!” she cried. “I only stayed to go to that silly dinner party. What a fool I was!”

At that very moment a loud sound of wailing broke out from the servants’ quarters. The woman clutched the young man’s arm. The wailing grew wilder and wilder.

“What is it? What is it?” Mrs. Lennox gasped.

“Someone died,” answered the officer. “The epidemic broke out among your servants[4].”

“I did not know!” Mother cried. “Come with me! Come with me!” and she turned and ran into the house.

Soon Mary learned everything. The cholera has broken out and people were dying like flies. Her Ayah was ill, and then she died. That is why the servants were wailing. Before the next day three other servants were dead and others ran away in terror. There was panic on every side, and dying people in all the bungalows.

During the confusion and bewilderment of the second day Mary hid herself in the nursery. Everyone forgot her. Nobody thought of her, nobody came to her, and strange things happened of which she knew nothing. Mary cried and slept. She only knew that people were ill and that she heard mysterious and frightening sounds. Once she crept into the dining-room and found it empty. A partly finished meal was on the table. The child ate some fruit and biscuits. She was thirsty, so she drank a glass of wine. It was sweet, and she did not know how strong it was. Very soon it made her intensely drowsy. She went back to her nursery and shut herself in again. The wine made her sleepy. She lay down on her bed and knew nothing more for a long time.

Many things happened during the hours in which she slept so heavily, but she was not disturbed by the wails.

When she awakened she lay and stared at the wall. The house was perfectly still. She heard neither voices nor footsteps. Who will take care of her now? Ayah was dead. There will be a new nurse, and perhaps she will know some new stories. Mary was rather tired of the old ones. She did not cry because her nurse was dead. She was not an affectionate child and never cared much for anyone. The noise and wailing over the cholera frightened her, and she was angry because no one remembered that she was alive. Everyone was too panic-stricken to think of a little girl. No one loved her. When people have the cholera they remember nothing but themselves.

No one came. She lay waiting and the house was growing more and more silent. She heard something on the matting. When she looked down she saw a little snake. The snake was watching her with eyes like jewels. She was not frightened, because it was a harmless little thing. The snake slipped under the door as she watched it.

“How queer and quiet it is,” she said. “Is there anyone in the bungalow?”

Almost the next minute she heard footsteps in the compound, and then on the veranda. They were men’s footsteps, and the men entered the bungalow and talked in low voices. No one went to meet or speak to them. They opened doors and looked into rooms.

“What desolation!” she heard one voice say. “That pretty, pretty woman! I suppose the child, too. I heard there was a child, though no one ever saw her.”

Mary was standing in the middle of the nursery when they opened the door a few minutes later. She was frowning because she was hungry. The first man who came in was a large officer. He looked tired and troubled. When he saw her he was startled.

“Barney!” he cried out. “There is a child here! A child alone! In a place like this!”

“I am Mary Lennox,” the little girl said. She thought the man was very rude to call her father’s bungalow “a place like this”. “I fell asleep when everyone had the cholera. I have just wakened up. Why does nobody come?”

“It is the child no one ever saw!” exclaimed the man, turning to his companions.

“Why does nobody come?” Mary asked.

The young man whose name was Barney looked at her very sadly.

“Poor little kid!” he said. “There is nobody here.”

Mary found out that she had neither father nor mother left. They died in the night, and the servants left the house quickly. That was why the place was so quiet. It was true that there was no one in the bungalow but herself and the little snake.

Chapter II

Mistress Mary quite contrary

Mary knew very little of her mother. She did not miss her at all, in fact, she was a self-absorbed child.

They took her to the English clergyman’s house. She knew that she was not going to stay there long. She did not want to stay. The English clergyman was poor and he had five children. They wore shabby clothes and were always quarreling and snatching toys from each other. Mary hated their untidy bungalow and was very disagreeable to them. Nobody wanted to play with her.

Basil was a little boy with impudent blue eyes and a turned-up nose and Mary hated him. She was playing by herself under a tree. She was making heaps of earth and paths for a garden and Basil came and stood near to watch her. Suddenly he made a suggestion.

“Why don’t you put a heap of stones there?” he said. “There in the middle,” and he leaned over her to point.

“Go away!” cried Mary. “Go away!”

For a moment Basil looked angry, and then he began to tease. He was always teasing his sisters. He danced round and round her and made faces[5] and sang and laughed:

“Mistress Mary, quite contrary,How does your garden grow?With silver bells, and cockle shells,And marigolds all in a row.”He sang it until the other children heard and laughed, and sang “Mistress Mary, quite contrary”. After that they called her “Mistress Mary Quite Contrary” when they spoke of her to each other, and often when they spoke to her.

“They will send you home,” Basil said to her, “at the end of the week. And we’re glad of it.”

“I am glad of it, too,” answered Mary. “Where is home?”

“She doesn’t know where home is!” said Basil, with scorn. “It’s England, of course. Our grandmama lives there and our sister Mabel came to her last year. You are not going to your grandmama. You have none. You are going to your uncle. His name is Mr. Archibald Craven.”

“I don’t know anything about him,” snapped Mary.

“I know you don’t,” Basil answered. “You don’t know anything. Girls never do. I heard father and mother talking about him. He lives in a great, big, desolate old house in the country and no one goes near him. He’s a hunchback, and he’s horrid.”

“I don’t believe you,” said Mary; and she turned her back and stuck her fingers in her ears, because she did not want to listen any more.

Mrs. Crawford told her that night that she was going to sail away to England in a few days and go to her uncle, Mr. Archibald Craven, who lived at Misselthwaite Manor. Mary looked so stony and stubbornly uninterested that they did not know what to think about her. They tried to be kind to her, but she only turned her face away when Mrs. Crawford attempted to kiss her.

“She is such a plain child,” Mrs. Crawford said pityingly, afterward. “And her mother was such a pretty creature. She had a very pretty manner, too, and Mary has the most unattractive ways I ever saw in a child. The children call her ‘Mistress Mary Quite Contrary’. Though it’s naughty of them, I can understand it. Her mother scarcely ever looked at her. When her Ayah was dead, no one thought about the girl. The servants ran away and left her all alone in that deserted bungalow. Colonel McGrew said he was very surprised when he opened the door and found her in the middle of the room.”

Mary made the long voyage to England under the care of an officer’s wife, who was taking her children to leave them in a boarding-school[6]. She was rather glad to hand the child over to the woman whom Mr. Archibald Craven sent to meet her, in London. The woman was his housekeeper at Misselthwaite Manor, and her name was Mrs. Medlock. She was a stout woman, with very red cheeks and sharp black eyes. She wore a very purple dress, a black silk mantle and a black bonnet with purple velvet flowers which trembled when she moved her head. Mary did not like her at all, but as she very seldom liked people there was nothing remarkable in that.

“My God!” Mrs. Medlock said. “And we heard that her mother was a beauty.”

“Perhaps she will improve as she grows older,” the officer’s wife said. “Children alter so much.”

Mary was watching the passing buses and cabs, and people. She was very curious about her uncle and the place he lived in. What sort of a place was it, and what is he like? Why is he a hunchback?

Mary began to feel lonely and to think queer thoughts which were new to her. She wondered why she never belonged to anyone even when her father and mother were alive. Other children belonged to their fathers and mothers. She had servants, and food and clothes, but no one took any notice of her. She did not know that this was because she was a disagreeable child. But, of course, she did not know she was disagreeable. She often thought that other people were, but she did not know that she was so herself.

Mrs. Medlock had a comfortable, well paid place as housekeeper at Misselthwaite Manor. She never dared to ask a question.

“Captain Lennox and his wife died of the cholera,” Mr. Craven said. “Captain Lennox was my wife’s brother and I am their daughter’s guardian[7]. The child will be here. You must go to London and bring her here.”

So she packed her small trunk and made the journey.

Mary sat in her corner of the railway carriage and looked plain and fretful. She had nothing to read or to look at. She folded her thin little hands in her lap.

“I suppose I may tell you something about where you are going to,” Mrs. Medlock said. “Do you know anything about your uncle?”

“No,” said Mary.

“Never heard your father and mother talk about him?”

“No,” said Mary frowning. Her father and mother never talked to her about anything.

“Humph,” muttered Mrs. Medlock.

She did not say any more for a few moments and then she began again.

“I suppose I can tell you something-to prepare you. You are going to a queer place.”

Mary said nothing at all.

“It’s a grand big gloomy place, and Mr. Craven is proud of it. The house is six hundred years old. It’s on the edge of the moor. There are many rooms in it, though many rooms are locked. There are many pictures and fine old furniture and things in the manor. There is a big park round it and gardens and trees.” She paused. “But there is nothing else,” she ended suddenly.

Mary listened to her. It was so unlike India.

“Well,” said Mrs. Medlock. “What do you think of it?”

“Nothing,” the girl answered. “I know nothing about such places.”

Mrs. Medlock laughed.

“Eh!” she said, “you are like an old woman. Don’t you care?[8]”

“It doesn’t matter,” said Mary, “whether I care or not.”

“You are right,” said Mrs. Medlock. “It doesn’t. Why will he keep you at Misselthwaite Manor? I don’t know. He’s not going to trouble himself about you, that’s certain.”

She paused.

“He’s got a crooked back,” she said. “He was a sour young man[9]. But then he was married.”

Mary’s eyes turned toward her. She was a little surprised. Mrs. Medlock saw this, and as she was a talkative woman she continued with more interest.

“She was a sweet, pretty girl. People said she married him for his money. But she didn’t-she didn’t. “When she died…”

“Oh! did she die!” Mary exclaimed. She remembered a French fairy story. It was about a poor hunchback and a beautiful princess.

“Yes, she died,” Mrs. Medlock answered. “And it made him queerer than ever. He cares about nobody. He doesn’t want to see people. Most of the time he goes away, and when he is at Misselthwaite he shuts himself up in the West Wing. Only Pitcher sees him. Pitcher is an old man, but he took care of him when he was a child and he knows him very well.”

It did not make Mary feel cheerful. A house with a hundred rooms, with their doors locked-a house on the edge of a moor-sounded dreary. A man with a crooked back who shut himself up also! She stared out of the window with her lips pinched together.

“Don’t expect to see him, because you won’t,” said Mrs. Medlock. “And you mustn’t expect that there will be people to talk to you. You’ll play about and look after yourself. They will tell you what rooms you can go into and what rooms you can’t. There are gardens nearby. But when you’re in the house don’t go wandering. Mr. Craven doesn’t like it.”

“I don’t want to go wandering,” said sour little Mary.

And she turned her face toward the window. Soon she fell asleep.

Chapter III

Across the moor

She slept a long time, and when she awakened Mrs. Medlock bought a lunchbasket at one of the stations. They had some chicken and cold beef and bread and butter and some hot tea. The rain was streaming down heavily and everybody in the station wore wet and glistening waterproofs. The guard lighted the lamps in the carriage, and Mrs. Medlock cheered up very much over her tea and chicken and beef. Mary sat and stared at her until she fell asleep once more in the corner of the carriage.

It was quite dark when she awakened again. The train stopped at a station and Mrs. Medlock was shaking her.

“It’s time to open your eyes!” she said. “We’re at Thwaite Station and we’ve got a long drive before us.”

Mary stood up while Mrs. Medlock collected her parcels. The little girl did not offer to help her, because in India native servants always picked up or carried things.

The station was small. The station-master spoke to Mrs. Medlock, pronouncing his words in a queer fashion which Mary found out afterward was Yorkshire,

“The carriage is waiting outside for you.”

A brougham stood on the road before the little platform. Mary saw that it was a smart carriage and that it was a smart footman.

When he shut the door, mounted the box with the coachman, and they drove off, the little girl sat and looked out of the window. She was not at all a timid child and she was not frightened.

“What is a moor?” she said suddenly to Mrs. Medlock.

“Look out of the window in about ten minutes and you’ll see,” the woman answered. “We’ll drive five miles across Missel Moor before we get to the Manor. You won’t see much because it’s a dark night, but you can see something.”

Mary asked no more questions. They passed a church and a vicarage and a little shop. Then they were on the highroad and she saw hedges and trees. At last the horses began to go more slowly. She could see nothing, in fact, but a dense darkness on either side.

“It’s not the sea, is it?” said Mary, looking round.

“No, not it,” answered Mrs. Medlock. “Nor it isn’t fields nor mountains, it’s just miles and miles and miles of wild land that nothing grows on but heather and gorse and broom, and nothing lives on but wild ponies and sheep.”

On and on they drove through the darkness. The road went up and down.

“I don’t like it,” Mary said to herself. “I don’t like it at all.”

They drove out of the vault into a clear space and stopped before an immensely long house. The entrance door was a huge one made of massive panels of oak. It opened into an enormous hall with the portraits on the walls and the figures in the suits of armor.

A neat, thin old man stood near the manservant who opened the door for them.

“You will take her to her room,” he said in a husky voice. “He doesn’t want to see her. He’s going to London in the morning.”

“Very well, Mr. Pitcher,” Mrs. Medlock answered.

Then Mary Lennox went up a broad staircase and down a long corridor and through another corridor and another, until a door opened in a wall and she found herself in a room with a fire in it and a supper on a table.

Mrs. Medlock said unceremoniously:

“Well, here you are! This room and the next are where you’ll live-and stay here. Don’t forget that!”

Chapter IV

Martha

When Mary opened her eyes in the morning it was because a young housemaid came into her room to light the fire. She was raking out the cinders[10] noisily. Mary lay and watched her for a few moments and then began to look about the room. The room was curious and gloomy. The walls were covered with tapestry with a forest scene embroidered on it. There were fantastically dressed people under the trees and in the distance there was a castle. There were hunters and horses and dogs and ladies.

Out of a deep window Mary saw a great stretch of land which had no trees on it, and looked rather like an endless, dull, purplish sea.

“What is that?” she said, pointing out of the window.

Martha, the young housemaid, looked and said,

“That’s the moor. Do you like it?”

“No,” answered Mary. “I hate it.”

“That’s because it’s too big and bare now. But you will like it.”

“Do you?” inquired Mary.

“Yes, I do,” answered Martha. “I just love it. It’s lovely in spring and summer.”

Mary listened to her with a grave, puzzled expression. The native servants in India were not like Martha. They were obsequious and servile. They called their masters “protector of the poor”. It was not the custom to say “please” and “thank you” and Mary always slapped her Ayah in the face[11] when she was angry.

This girl was round, rosy and good-natured.

“You are a strange servant,” she said from her pillows.

Martha sat up on her heels.

“Eh! I know that,” she said. “Mrs. Medlock gave me the place out of kindness[12].”

“Are you going to be my servant?” Mary asked.

“I’m Mrs. Medlock’s servant,” she said stoutly. “And she’s Mr. Craven’s. I’ll do some housemaid’s work up here and help you a bit. But you won’t need much.”

“Who is going to dress me?” demanded Mary.

Martha sat up on her heels again and stared. She was amazed.

“Can’t you dress yourself?” she asked.

“What do you mean?” said Mary.

“I mean can’t you put on your own clothes?”

“No,” answered Mary, quite indignantly. “I never did in my life. My Ayah dressed me, of course.”

“Well,” said Martha, “it’s time you must learn.”

“It is different in India,” said Mistress Mary disdainfully.

“Eh! I can see it’s different,” Martha answered almost sympathetically. “When I heard you were coming from India I thought you were black.”

Mary was furious.

“What!” she said. “What! You thought… You-you daughter of a pig!”

“Who are you talking about?” asked Martha. “You needn’t be so vexed.”

Mary did not even try to control her rage and humiliation.

“You thought I was a native! You dared! You don’t know anything about natives! They are not people-they’re just servants. You know nothing about India. You know nothing about anything!”

She was in such a rage and felt so helpless, that she threw herself face downward on the pillows and burst into passionate sobbing. Martha went to the bed and bent over her.

“Eh! You mustn’t cry like that!” she begged. “Yes, I don’t know anything about anything-just like you said. I beg your pardon, Miss. Do stop crying.”

There was something comforting and really friendly in her queer Yorkshire speech. Mary gradually ceased crying and became quiet. Martha looked relieved.

“It’s time for you to get up now,” she said. “Mrs. Medlock said to carry your breakfast and tea and dinner into the room next to this. I’ll help you with your clothes.”

When Mary at last decided to get up, the clothes Martha took from the wardrobe were not hers.

“Those are not mine,” she said. “Mine are black.”

She looked at the thick white wool coat and dress, and added with cool approval:

“Those are nicer than mine.”

“Mr. Craven ordered Mrs. Medlock to get in London for you,” Martha answered. “He said he did not like black clothes.”

“I hate black things, too,” said Mary.

Martha helped to dress her little sisters and brothers but she never saw a child who stood still and waited for another person to do things for her.

“Why don’t you put on your own shoes?” she said when Mary quietly held out her foot.

“My Ayah did it,” answered Mary, staring. “It was the custom.”

“Eh! You did not see my family,” Martha said. “We are twelve, and my father only gets sixteen shilling a week. My mother cooks porridge for them all. They tumble about on the moor and play there all day. Our Dickon is twelve years old and he’s got a young pony.”

“Where did he get it?” asked Mary.

“He found it on the moor and he began to make friends with it and give it bits of bread and some grass. And it follows him everywhere. Dickon is a kind lad, animals like him.”

Mary did not have an animal pet of her own. So she began to feel a slight interest in Dickon. When she went into the next room, she found that it was a grown-up person’s room, with gloomy old pictures on the walls and heavy old oak chairs. There was a good substantial breakfast on the table in the center. But she always had a very small appetite.