Полная версия

A Clock of Stars: The Shadow Moth

Before Miroslav could answer, the king jumped up. ‘Damn it!’ he shouted, climbing on to the desk. ‘It’s one of those moths – the ones that eat cloth.’ The king swatted the air above his head. ‘If that thing has got at my silk, there’ll be hell to pay!’

A pale purple moth fluttered above him, just out of reach. ‘Quick, boy, go and fetch a servant!’ cried the king. ‘Tell them to bring a net!’ The moth flapped away, circled the giant orange stone and settled on the five-hundred-year-old vase. Miroslav followed it.

‘Kill that moth!’ shouted the king. Miroslav could hear his uncle scrambling down from the table.

He approached the vase cautiously. The moth was beautiful, with wings like faded peacock feathers. His uncle was advancing at speed. ‘Move out of the way!’ cried the king.

Miroslav pounced. He caught the insect in his cupped hands and hopped aside. His uncle came careering towards him, tripped over a stuffed lynx and – for a moment – was suspended in mid-air, before he flew towards the vase.

There was a terrible crash followed by a howl. The guards dashed in and Miroslav dashed out. He ran to the nearest window and released his prisoner. The moth fluttered away, leaving spots of silvery dust on his palms.

The evening began like clockwork. The sun slipped down and, as if connected to it by invisible pulleys, the crescent moon swung into position. It was the kind of dusk where even a passing moth sounds mechanical – with the soft whirring of wind-up wings.

The stars turned on, the city lights turned out and, at the top of the second tallest tower, the stage was set. A long table had been erected. It was piled high with tempting delicacies: candied orange peel, airy pastries filled with lemon curd and pistachio truffles. The boy had lit the candles again and the room was ablaze with light.

Servants, balancing a dish in either hand, careered past each other, with all the pace and poise of prima ballerinas. There were too many of them for the space, but somehow they managed their movements without touching each other. Conducting the performance, standing on a chair so his gestures could be seen, was the boy.

Imogen entered the room and looked about in amazement. Marie stared too, her eyes like saucers. The boy clapped his hands and the dance came to an abrupt end. ‘Please,’ he said, hopping down from his chair. ‘Have a seat.’ Chairs were pulled back. Napkins were placed on laps.

The only diners seemed to be Imogen, Marie and the boy. He’d changed his outfit for the occasion, and was now sporting a blue tunic covered in gold stars. His boots had pointy toes and flared out at the top, where they almost touched his knees.

‘Sparkling wine, madam?’ asked a servant with a curled moustache.

‘Er, no thank you,’ said Imogen, wrinkling her nose.

‘Perhaps some Parlavar?’ The servant brandished a bottle of pink liquid. Imogen shook her head.

‘Red Ramposhka?’

‘I’m eleven,’ said Imogen. ‘I normally drink lemonade.’

The servant straightened up. ‘Hmm, limon-eeeed. I’m afraid we don’t have that vintage.’

There was a lot of cutlery. Five knives, six forks and three spoons. Imogen caught sight of her warped face in a dessertspoon. What on earth, she wondered, was she supposed to do with all this?

A chain of servants passed dishes up and down the spiral staircase – taking away the empty plates and bringing up more food. During one course, a violinist played and Marie clapped along, even though it wasn’t the right kind of music for that.

At the end of the third course, Imogen turned to the boy. ‘Isn’t it strange?’ she said. ‘We’re all here, eating together, but we haven’t even been properly introduced.’

‘What do you want to know?’

‘Your name would be a good start.’

The boy cleared his throat. ‘I’m Prince Miroslav Yaromeer Drahomeer Krishnov, Lord of the City of Yaroslav, Overseer of the Mountain Realms and Guardian of the Kolsaney Forests.’

‘And what do people call you?’ said Imogen.

‘Your Highness.’

‘No, I mean what do your friends call you?’

The boy looked uncomfortable. ‘Your Royal Highness?’

‘I don’t believe you,’ said Imogen.

‘You can call me Prince Miroslav, son of Vadik the Valiant … or Miro. That’s the name my mother used.’

‘Miro,’ said Marie. ‘That’s a nice name.’

They tucked into the fourth course: honey-roast pig and steaming, buttered veg. Imogen attacked it with a soup spoon. Marie tried the fish knife.

‘Don’t you want to know our names?’ asked Imogen. Then, not bothering to wait for an answer, she said, ‘I’m Imogen Clarke and she’s Marie Clarke. We’re sisters.’

‘Sisters. I se—’

Suddenly the conversation was interrupted by a terrible scream. The girls dashed to the nearest window. ‘It’s the monsters again!’ said Marie. ‘It sounded like it came from over there.’ She pointed to the city outskirts.

Miro helped himself to mint tea and waited for his guests to return to their seats.

Imogen peered at him. ‘You don’t seem very concerned.’

He shrugged. ‘It’s normal.’

‘What are they?’ asked Marie.

‘The skret,’ said the boy.

‘Skretch?’

‘Well, you certainly can’t be from the forests if you’ve never heard of skret.’

‘We’re not really from the forests,’ said Marie. ‘Please … tell us about the monsters.’

‘The skret are nocturnal mountain creatures,’ said Miro. ‘They’re not much bigger than you or me, but they have bald heads like old men and they can see in the dark. Their teeth are sharp and their hands are clawed. Sometimes they walk like humans and sometimes they crawl like spiders. They come down from the mountains at dusk, running through the city and killing anything they find. If you don’t have skret where you’re from, you’re lucky.’ He took a sip of his tea. He was clearly enjoying having an audience.

‘Was it skret that were chasing us last night?’ asked Imogen.

Miro nodded.

‘And they would have eaten us if they’d caught us?’

‘No, no,’ said the boy.

‘That’s a relief!’ said Imogen, remembering how afraid she’d been. ‘They’d kill you all right – make a nice mess of your body.’

‘Oh.’

‘But I was joking when I said they ate people.’

Hilarious, thought Imogen.

‘Can’t you stop them from getting into the city?’ asked Marie.

‘My uncle tries. He’s the king, you see. He has the guards shut the city gates at nightfall. And he told everyone to put skret bones out, to show the monsters what happens if they keep coming here … but none of it seems to work. That’s why we ring the bells: to warn everyone that the skret are on their way. Of course, none of this happened when my parents were about. The skret weren’t a problem back then …’

Imogen didn’t speak. She was thinking about the little skulls, with the triangular teeth, that decorated the houses.

‘But we’re safe up here,’ said the prince, signalling to the servants to clear away the plates.

‘Shouldn’t we have the lights out? Like other people do?’ asked Marie, looking around at the candles.

‘Oh no. The skret can’t get into the castle, let alone all the way up my tower. They aren’t smart or big enough. Their brains are only a third the size of a human brain.’

‘Sometimes,’ said Marie, ‘even little things can be quite fierce.’

‘Besides,’ said the boy, ‘I’ve got weapons. I’d have no problem fighting off a few monsters.’

Imogen blinked at him. She thought that highly unlikely.

‘Where are your parents?’ she asked. ‘You said things were different when they were about.’

‘Oh. Yes. They’re with the stars now … I don’t think we need to …’ Miro ran his fingers through his thick curly hair.

There was a pause.

‘Would you like some tea?’ He filled up their cups. ‘I tried to organise a dancing bear for tonight – one of the small ones – but apparently they can’t catch them any more. There’s a dancing bear shortage.’ He snorted with laughter. Imogen didn’t get the joke.

‘So how did you come to be running from skret through my city?’ he asked. ‘If you’re not peasants, and you’re not from the forests, where are you from?’

‘Ah,’ said Imogen. ‘Well, that’s kind of complicated.’

As they drank mint tea, Imogen told the prince about her journey through the Haberdash Gardens. She didn’t mention the shadow moth. She didn’t feel like sharing all of her story with Miro and her sister. Not just yet.

Marie kept interrupting, but she got things mixed up so Imogen had to tell her to be quiet. When Imogen got to the part about the door in the tree, Marie piped up again. She made it sound as though she had helped find it. Imogen lost no time putting things straight: ‘Marie just followed me. She’s always copying my ideas.’

‘Am not.’

‘Are too.’

‘I want to hear the rest of the story,’ said Miro, so Imogen kept going.

She finished at the moment when she and Marie entered the city. The prince asked, ‘What about the bit where I rescued you? You haven’t told that part.’

‘Well, you know what happened then. I don’t need to tell you,’ said Imogen.

‘I should like to hear it all the same.’

‘Don’t be ridiculous. I’m not telling you a story about yourself.’

‘I am the prince and I want to hear it.’

Imogen rolled her eyes. ‘Fine. Marie, you can tell this bit.’

Marie finished the story, telling it with too many frilly words and too favourable a portrayal of the prince.

‘Anyway,’ cut in Imogen, ‘the point is we need to get home.’

Two pairs of eyes turned to Miro. ‘I have to admit,’ he said, ‘I’ve never heard of this garden kingdom or the queen who rules it.’

‘She’s not a queen,’ said Imogen. ‘She’s just Mrs Haberdash.’

‘I’ve certainly never heard of anyone putting a door in a tree. The people where you come from must be very odd.’

‘Are you going to help us get home?’ said Imogen. ‘Because, if you’re not, we might as well leave now.’ She pushed back her chair to show she meant business.

‘Right after we’ve finished pudding,’ added Marie.

Miro started fiddling with his rings. Tonight he had several stacked on his index fingers and a big one on each thumb. ‘I thought I was doing you a favour,’ he muttered. ‘I rescued you from the skret and I let you stay for dinner, even though you’re peasants.’

‘Stop turning your rings,’ said Imogen. ‘It’s driving me mad. We’re not peasants and I’m sure we can find the door on our own if we have to. I just thought, what with you being a prince and all, you’d be able to do something. I thought you’d at least have a servant who could make the door open. It’s not as if we’re asking you to slay a dragon.’

That hit the mark. The prince’s face flushed. ‘My ancestors killed this kingdom’s last dragon.’

‘That’s a shame,’ said Imogen.

Silence.

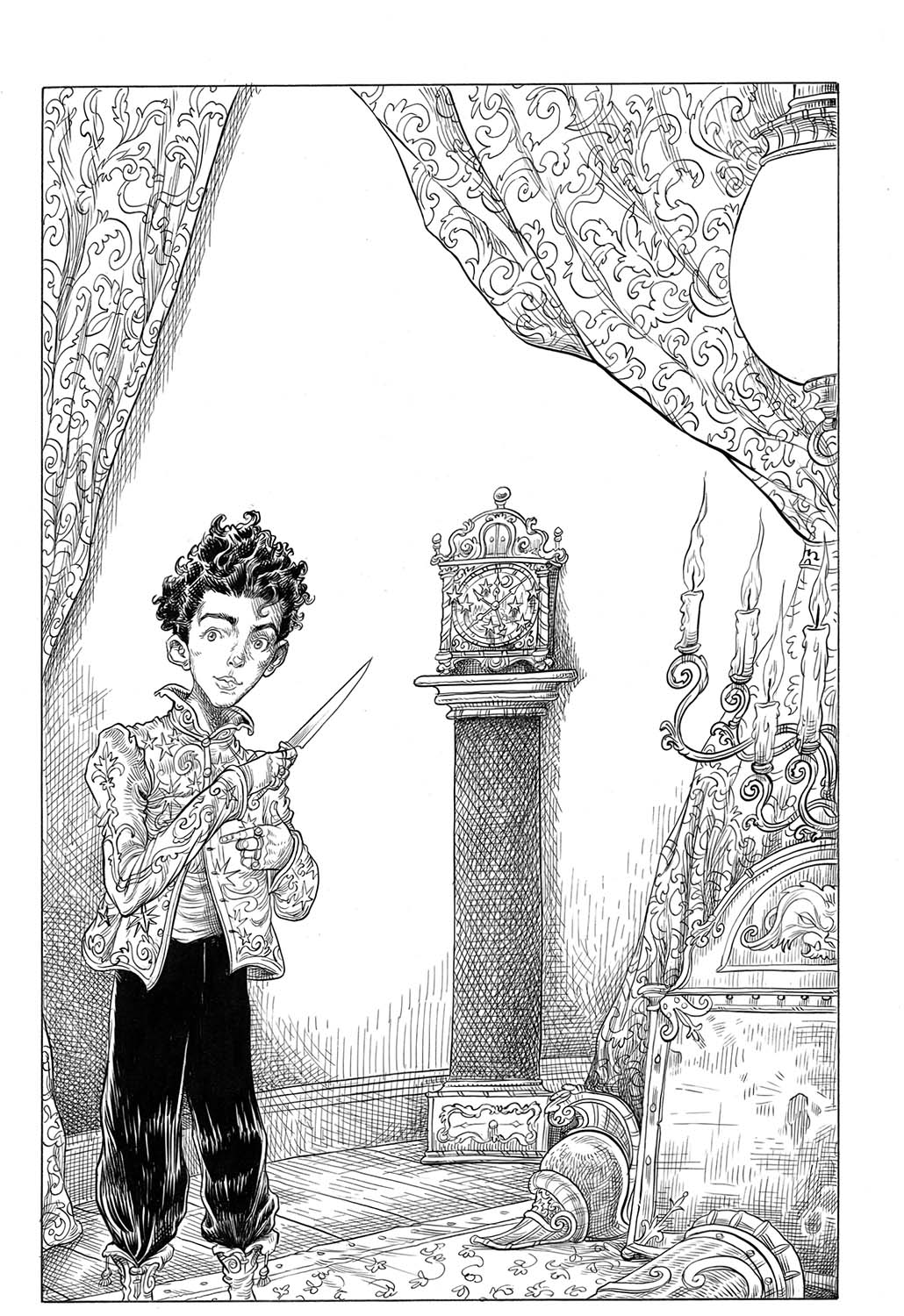

‘Okay,’ said the boy. ‘I’ll help you. In fact, I’ll make a pact.’ He rummaged through an old chest and pulled out a dagger. Marie gave a squeak.

‘Don’t worry,’ said Miro. ‘I only need one drop.’

‘One drop of what?’ said Marie.

‘Your blood, of course.’

‘My blood?’

‘Not just yours – everyone has to give a bit. That’s how we seal the pact.’

‘Can’t we just shake hands?’ said Imogen.

‘Or cross our hearts?’ said Marie.

‘I’ll go first,’ said Miro.

The three children stood together underneath the old clock with the sleeping face. Miro held up his left thumb for the girls to see, like a magician about to do a trick. In his right hand, the blade glinted. He touched the soft pad of his thumb with the tip. ‘I promise to do everything within my powers to help these two peasa—’

‘—Imogen and Marie.’

‘—To help Imogen and Marie get home.’ He looked at them, seeking approval. Imogen nodded.

The blade was sharp. A little pressure and it pierced his skin, bringing up a ruby-red drop of blood. He turned to hide his face, but it was too late; Imogen had seen him wince. He held out the dagger. ‘Now you.’

‘What am I supposed to be promising?’ she asked.

‘To be my loyal subjects,’ said Miro.

Imogen didn’t take the dagger. ‘Loyal subjects? What does that even mean?’

‘You know … you go where I go. Have dinner with me and things.’

‘What things?’ she demanded.

‘Go fishing. Play in the gardens. Whatever I fancy,’ said the prince.

Imogen snorted. ‘You mean be your friends? You want us to promise to be your friends?’

‘Call it what you will.’

‘You must be joking,’ she said, but the prince’s expression was deadly serious. He offered her the dagger again.

‘Just until we go home?’ she said. ‘You know we’re not staying long?’

‘Oh yes,’ said the prince. ‘Just until you go home.’

Imogen took the dagger. ‘This is absurd.’ She placed the blade on her thumb. ‘Okay, I promise to hang around with Miro, to be his loyal … friend. Just until we go home.’

‘Great, now do the—’

‘I know, I know.’ Imogen pricked her skin and passed the dagger to Marie.

‘I won’t do it,’ said Marie.

‘You will too,’ said Imogen.

‘Why? Why should I have to?’

‘Because, Marie, if you don’t do it, you haven’t earned your ticket home.’

‘It doesn’t need two of us, does it?’ said Marie and she turned to Miro with a pleading expression.

‘One of you is probably enough,’ said the prince.

‘Oh, stop being such a baby,’ said Imogen and she grabbed Marie’s wrist. ‘Repeat after me: I promise …’

‘Imogen!’ cried Marie.

‘Don’t wriggle. I’m only drawing a bit of blood, not cutting off your hand.’

‘You’re hurting me!’

‘Come on,’ said Miro. ‘I think two of us is enough.’

‘Oh, fine. Be a baby.’ Imogen released Marie’s wrist.

Imogen and Miro pressed their thumbs together. ‘That’s it,’ said Miro. ‘The pact is sealed.’

As they stepped apart, the clock behind them sprang into motion. The hands spun, cogs whizzed and mechanical stars flew about. It was going too fast: chiming for midnight, then midday, skipping through days in seconds.

Suddenly it all stopped, or rather it started behaving like a normal clock. The hands ticked along as if they had never been doing anything different.

This time, as the clock reached midnight, the little hatch opened and a carving of two girls trundled out. The smaller one had long wavy hair in a ponytail. The taller one had short straight hair.

The miniature girls curtseyed, turned a full circle and went back into the clock. The hatch closed behind them.

Imogen lay in the big bed at the top of the second tallest tower. Her thumb had stopped bleeding and, with her belly full of food, she fell asleep in no time. But, as so often happens when you’re not sleeping in your own bed, Imogen slept fitfully, and her dreams were strange and frightening.

She was back at home. She could hear her mum in the bathroom, making crying sounds. Imogen opened the door and Mum was sitting in the bath, fully dressed. She hadn’t run the water yet. She was just staring at the taps, as if stuck on the question of whether to turn them on.

This was what Mum had done in real life when Ross, an old boyfriend, dumped her, but that was years ago. Imogen knelt by the bath and peeped over the side. Mum’s make-up was smeared down her cheeks.

‘Is it Mark?’ said Imogen. ‘Did you have a fight?’

Mum looked confused.

‘You know, your friend that you went to the theatre with?’

The bathroom started filling with water. It lapped against Imogen’s legs, but she didn’t move.

‘I know Mark,’ said Mum, ‘but who are you?’

‘It’s me … it’s Imogen.’ The water in the bathroom crept up to her waist.

‘How did you get into the house?’

‘Come on, Mum. We’ve only been gone one night—’

‘Where’s Mark?’ said Mum in a shrill voice.

Imogen stood up as the water flowed into the bath, making Mum’s clothes balloon. ‘You have to get up,’ said Imogen, holding out her hand. ‘The room’s going under.’

But Mum just closed her eyes as the water sloshed across her face. She was gripping on to the bath with both hands.

The water lifted Imogen off the floor and she began to panic. She swam back to Mum and shook her by the shoulder. Mum opened her eyes and smiled. ‘It’s okay,’ she mouthed.

‘No, it’s not!’ cried Imogen in a voice full of bubbles.

She came up for air. The water had nearly reached the ceiling. Why wouldn’t Mum listen? How could she have forgotten them already?

Then she heard a strange sound … bells. There were bells in the bathroom.

Imogen opened her eyes, coming to the surface for a second time. She was lying in a four-poster bed. Her mum was nowhere to be seen. The bells of Yaroslav were ringing for dawn and it was raining.

Imogen lay still until the last bell tolled. It was just a dream. Of course Mum knew who she was. She was probably looking for them right this minute. She’d never forget her girls. Would she?

Imogen turned over to see Marie asleep next to her. Miro was curled up at the foot of the bed like an overindulged poodle. He opened his eyes as his clock began to chime. A new figure came out of the hatch. It was a hunter. He shot an imaginary arrow from his tiny bow before disappearing back inside the clock.

Miro yawned and said:

‘You cannot trust a hunter,

for you never really know

if it’s just the deer he’s after,

with his arrows and his bow.’

‘What’s that?’ asked Imogen.

‘Just an old rhyme,’ said Miro. Suddenly, he sat bolt upright. ‘Huntsman. Now there’s a thought! We could get Blazen Bilbetz to help find the door in the forests.’

‘Who’s Blar-zen?’

Miro glanced at Imogen with disbelief. ‘You don’t know Blazen Bilbetz? He’s only the best hunter in Yaroslav. I bet he’d be able to find your door in no time, and I bet he’d kick it open. After all, the forests are his hunting grounds. Let’s go and ask him. Wake Marie.’

Imogen glanced at her sister. She looked so peaceful, like a sleeping baby. ‘Let’s go without Marie. She’ll only slow us down.’

‘Won’t she be sorry to be left behind?’

‘Probably, but she’s no good on adventures. We’ll come back for her in a few hours – when it’s all sorted.’

If only it had been that easy. It would be many hours before Imogen and Miro returned.

That same day, in a big house by the river, a young woman called Anneshka Mazanar received a very important invitation. She opened the front door to a pot-bellied man. He was wearing the crimson uniform of the Royal Guards and he’d been drenched by the rain.

He stared at Anneshka with his mouth slightly open, as if he’d slipped into a trance. Anneshka was used to people gawping at her and she didn’t really mind. In fact, she liked it. Her beauty was the talk of Yaroslav. They said that she’d been drawn, not born. They said that her heart-shaped face was perfect, with her violet eyes, pouty mouth and cascade of golden hair.

‘Can I help you?’ she asked.

The Royal Guard snapped back to life, brushing water from the tip of his nose. ‘Yes, miss, sorry, miss. I’ve got a letter for your father. Will you see that he gets it?’

‘Of course,’ said Anneshka, giving the guard one of her best smiles before snatching the letter and running to her room at the top of the house.

Her fingers trembled as she broke the royal seal. It was as she had hoped – it was an invitation from the king. The letter said that her parents were to visit the castle, along with their ‘charming’ daughter. Anneshka’s heart fluttered.

She looked out of her bedroom window, towards Castle Yaroslav. There was no way her parents were coming with her. No way in hell. It was her that the king wanted to see and her parents had only been invited for the sake of decency.

She read the letter again. The king said that it had been a ‘delight’ to meet her at the royal ball. Anneshka remembered it well. During her first dance with King Drakomor, she’d seen how handsome he was, with grey eyes and an elegant moustache.

During their second dance, she’d seen something else; something that other people missed. She’d seen that he wanted to be rescued. After that, winning his heart had been easy.

Although the ball had been Anneshka’s first encounter with the king, she’d had her mind’s eye on him for years. She’d known that she would be the queen of Yaroslav ever since she was seven. Anneshka’s mother had been plaiting her hair when she first told her the story.

‘The stars have great things in store for you,’ said her mother.

‘How do you know?’ said little Anneshka. Her mother had done her hair too tight and it hurt.

‘Hold still and I’ll tell you. The night that you were born, I was visited by the forest witch – the one they call Ochi. She was cast out of the city long ago and your father didn’t want her in the house, but I knew why she’d come. I told him to let her enter. The witch swaddled you and gave me something for the pain. Then she offered to read the stars.’

‘For me?’ said Anneshka. She wanted to turn round and look at her mother to see if she was telling the truth, but her mother pulled on her plait. Anneshka cried out.

‘I said hold still!’

‘Sorry, Mother … But what did the stars say?’

‘Ochi read your stars and I paid her well. Too well, some might say. When she was done with her stargazing, the witch came back to my bed and whispered in my ear. She said you would be a great queen.’

‘A great queen of where?’ said Anneshka.

‘Of Yaroslav, of course.’

‘But how will it happen? I’m not a princess …’

‘No,’ agreed her mother. ‘Your father’s not even the wealthiest man on this street, but I’ve spoken to him and it’s agreed. You will want for nothing. When fate comes calling, you’ll be ready.’

Anneshka’s mother gave her hair another twist. ‘There. You can move now. Your hair is done.’

It wasn’t until King Drakomor was crowned, and Anneshka came of age, that she saw her route to the throne. It was so obvious, as if that too had been written in the stars. King Drakomor did not have a wife.

Anneshka sat down at her writing desk to pen her reply to the king. She stroked her chin with the tip of the quill.

‘Now,’ she whispered, ‘how does Father normally begin his letters …?’

Imogen and Miro set out to find Blazen Bilbetz. Miro said they’d know the hunter when they saw him. He was built like a bear, the tallest man in Yaroslav, and clothed in the furs of the beasts that he’d killed.

Imogen borrowed a cloak to wear over her clothes and keep out the rain. Water washed off roofs and splashed down cobbled streets, forming little streams at the side of the road. Some people had shoved skret skulls on the ends of their gutters, like home-made gargoyles. Water rushed out through their jaws.