Полная версия

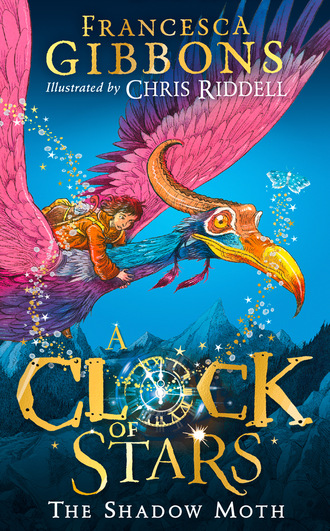

A Clock of Stars: The Shadow Moth

‘You must forgive my sister,’ said Imogen.

‘Hey! It wasn’t just me that tied him up!’

Imogen shot Marie a meaningful look. ‘She was dropped on her head as a baby.’

The boy looked at Marie with his far-apart eyes. ‘Is that what turned her hair orange?’

‘It’s not orange,’ said Marie. ‘It’s red.’

‘Looks orange to me,’ said the boy.

Imogen stepped between them. ‘Look, I think we got off on the wrong foot.’

The boy let out a long sigh. ‘You’re right,’ he said. ‘I don’t normally do that to guests. To be honest, I don’t normally have guests at all.’

‘What a surprise,’ muttered Imogen.

The boy didn’t seem to hear. ‘When my uncle has people to visit, the Royal Guards confiscate their weapons.’

‘Oh right,’ said Imogen, thinking that was probably the correct response.

‘So, when Petr’s not about, I have to take precautions.’

‘I see,’ said Imogen, who didn’t see at all.

‘How about we just start this whole thing again?’ said the boy.

‘A rematch?’ cried Marie.

‘No! Let’s say you just came through the door. Pretend you did. Yes, that’s it. And I’ve just locked it and you say, Hello, Your Majesty, what a pleasure to meet you.’

Imogen wasn’t sure about the script. She didn’t think the boy should cast himself as royalty. However, she was in a tricky situation. She needed his help.

‘Good evening, Your Majesty,’ she said, giving a wobbly curtsey. Marie did the same.

‘What a pleasure it is to meet you,’ said Marie.

The boy bowed low. ‘The pleasure is all mine,’ he said. ‘Welcome to Castle Yaroslav.’

‘I am the prince of this castle,’ said the boy, ‘and you are my most honoured guests.’ He straightened his jacket, checking that the stiff collar was still pointing up.

Throughout this performance, he kept a very serious face. Either he’s a good actor, thought Imogen, or he’s completely off his rocker.

‘Now!’ The boy picked up the candle. ‘Tell me … what were you doing out there? I thought the peasants rounded up their children at dusk. Not runaways, are you?’

‘To start with, we’re not peasants,’ said Imogen, puffing herself up to her full height. ‘As I said.’

‘What are you, then? Pickpockets?’

‘Of course not!’

‘Assassins?’ He took a step back.

‘We’re lost!’ said Imogen. ‘We’re not supposed to be here at all.’

‘Where are you supposed to be? Are you from the forests?’

‘I suppose you could say that …’

The boy moved the candle closer to Imogen. ‘You don’t look like you’re from the forests,’ he said, inspecting her T-shirt and jeans. ‘You’re not wearing enough green to be a lesni. In fact, what are you wearing? Are those nightclothes?’

Imogen clenched her fists and then released them, reminding herself that she needed all the help she could get.

‘You’ll have to stay here for the night,’ said the boy. ‘You’d be eaten alive out there.’ He seemed to take great delight in saying that last sentence. He glanced at the girls to see if his words had had any effect. Marie looked horrified.

‘That would be lovely,’ said Imogen. ‘Thank you.’

‘Excellent. Follow me.’ The boy walked away, taking the small circle of candlelight with him.

‘Do you think we should go with him?’ whispered Marie.

‘I don’t see what choice we’ve got,’ said Imogen.

‘It’s just that Mum always says not to go with strangers. Do you think he’s a stranger?’

‘He’s strange all right, but I’m pretty sure Mum wouldn’t want us eaten by monsters either.’

‘No,’ said Marie. ‘Although she never talked about it pacifically.’

‘It’s specifically. Anyway, if someone loves you, they don’t have to say don’t get eaten by monsters. It’s obvious.’

Imogen thought of Mum getting back from the theatre to find that the home-made pizzas were untouched. Mum always left them something special to eat if she was going to be late, and pizza was one of Imogen’s favourites.

Then she thought of Grandma, with her walking stick, searching the gardens. It made Imogen feel sad so she brushed the thought aside. ‘Come on,’ she said to Marie. ‘His Royal Highness is getting away.’

The girls followed the boy through tapestry-lined corridors and across rooms that were as big as the sports hall at school.

He stopped at the foot of a spiral staircase. ‘This is the entrance to my quarters,’ he said. ‘No commoners have ever set foot beyond this point. Apart from the servants, that is. You’ll be the first.’

Bonkers, thought Imogen as she nodded along.

The further up the stairs they climbed, the narrower the staircase became. ‘Keep up!’ shouted the boy, who had disappeared ahead.

The steps took them to a circular room. ‘I’ve never seen so many candles,’ said Imogen. ‘Is all this stuff yours?’

‘Yes,’ said the boy.

‘Where did you get this from?’ Marie’s enormous eye peered through a magnifying glass.

‘It was my father’s.’

‘And this?’ Marie lay down on a fur rug.

‘I don’t remember.’

‘What about this?’ asked Imogen, and she blew dust from from the sleeping face of an old clock.

‘Don’t touch that,’ snapped the boy. ‘It’s the only one of its kind.’

Imogen leaned in. She wanted a better look at the thing she mustn’t touch.

The clock was made of wood. In front of its face, there were five motionless hands and an array of jewelled stars. Imogen couldn’t work out what was holding the stars in place. They seemed to hover, but she couldn’t see any wires. A silver moon peeped out from behind the biggest hand, as if too shy to reveal itself fully.

‘What’s inside that hatch?’ asked Imogen, stepping back and pointing to a tiny door at the top of the clock. It was about the right size for a hamster.

‘I don’t remember,’ said the boy. ‘It stopped working years ago.’

‘Why?’ said Marie.

The boy fiddled with the rings on his fingers. ‘I think you’ve asked enough questions for one night.’

Marie cast a longing glance at the room’s four-poster bed, with its plumptious pillows and downy quilt. She looked at Imogen, who nodded. The next second, Marie was kicking off her shoes and wriggling under the sheets.

Imogen turned to the boy. ‘Just one more question …’

‘Yes?’

‘Why are you helping us?’

‘I told you,’ he said. ‘You’d be eaten alive if you stayed outside.’

‘But where are all the other people?’

‘They’re here. In their houses. Around the castle. I’m just the only one who keeps candles burning.’

Imogen walked to a window and looked out at the city shrouded in darkness. They had made it to the light that she’d seen from the forest. ‘We must be in the castle’s tallest tower,’ she said, half to herself.

‘Not quite,’ said the boy. ‘This is the second tallest tower.’

Imogen removed her shoes and slipped into bed next to Marie. ‘We should blow out the candles,’ she said, yawning.

‘Why would I do that?’ asked the boy.

‘It’s a fire hazard.’ She was parroting her mum. Mum was always banging on about fire hazards.

‘A fire what?’

But Imogen didn’t reply. She was already fast asleep.

As Imogen slept, monsters flitted in and out of the darkness below. Like grotesque shadow puppets, their forms danced across shuttered windows. They reclaimed the streets, calling to each other across the empty squares.

In the big houses near the cathedral, if you were to peep out at just the right moment, you’d see a silhouette squatting on top of the bell tower. It might look like a child. Or perhaps a very old man. But, if you dared to look closer, you’d see that its shoulders were too muscular, its arms were too long and its teeth were too sharp.

The monsters travelled from roof to roof. They tiptoed along gutters. They hid in eaves. They hung down from bedroom windows by their claws.

All night, the city belonged to them.

There was sunlight behind Imogen’s eyelids. Bells tolled. That was odd. There were no churches near her house. A cockerel crowed. Definitely odd.

And she couldn’t hear the familiar noises of home: her mum’s radio, the cat demanding breakfast. Where was the smell of fried eggs? She opened one eye. Where was her orange juice? She opened the other. Where was any of it?

And then Imogen remembered. Propped up on her elbows, she looked around, detangling her dreams from last night’s reality. The forest was real. The city full of bones was real. The boy who rescued them was real. In fact, he was awake and observing her from a chair by the fire.

Hmm, thought Imogen. What was the appropriate thing to say? Perhaps Good morning or How did you sleep? Those were the things Mum normally said to guests. But Imogen was the guest so she cut straight to the chase: ‘You have to take us back to the tea rooms. We’re not supposed to be here.’

The boy slouched in his chair. ‘Aren’t you supposed to say something like, Thanks for saving my life?’

Imogen hopped out of bed. ‘What time is it?’ she asked.

‘Morning,’ he said.

‘I can see that, but what’s the time?’ She pulled on her shoes and went to wake Marie.

‘What does it matter?’ said the boy. ‘There’s no rush.’

‘Of course there is. Our mum will be worried. Or angry. Or both.’

The boy’s feet didn’t quite touch the floor and he swung his legs as he spoke.

‘Don’t you remember?’ he said. ‘My clock’s broken. I don’t know the time. There are bells at dawn and bells at dusk. Everything in between is day. Why rush back to see a bunch of angry grown-ups anyway?’

‘I don’t want to go to school,’ murmured Marie, still half asleep.

The boy slid down from his chair and added, a little petulantly, ‘I thought you’d at least stay for an evening meal.’

‘What planet are you living on?’ said Imogen. ‘We’ve been gone all night. Mum must have got home ages ago and I bet Grandma’s called the police. They’ll be out there in the gardens, searching for us with dogs.’

‘Oh, come now. Peasants go missing all the time. Nobody goes looking for them. Especially not dogs.’

‘This is the last time I’m going to tell you: we – are – not – peasants.’

Marie was awake now and peering round the room with bleary eyes.

‘Come on, Marie,’ said Imogen. ‘We’re leaving.’

The boy ran to the door. ‘No, you’re not!’ he cried, blocking the exit. ‘I won’t allow it!’

Marie rubbed sleep from her eyes. ‘Imogen, I want to go home.’

‘I command you to stay!’ cried the boy.

‘Don’t worry,’ said Imogen, helping Marie out of bed. ‘We’re going. Put your shoes on.’

‘Is this how you repay your rescuer? Is this the way to treat a prince?’

‘I don’t care who you are,’ said Imogen. ‘Move!’

‘Shan’t.’ The boy glowered at the sisters.

Imogen considered her options. There was a pair of axes hanging above the fireplace. They looked heavy. There was a crossbow by the door. She had no idea how to work that. And then she saw a sword mounted on the wall by the bed.

She climbed on to the headboard.

‘What are you doing?’ said the boy.

Imogen held on to the four-poster bed with one hand and reached for the sword with the other.

‘Leave that alone!’ cried the boy. Imogen grabbed the sword’s hilt. She tugged at it until it swung free. The boy let out a little squeak. The sword was heavier than Imogen had expected and it fell to the floor with a thud. Marie ran over, suddenly wide awake and eager to help. She picked up the sword with two hands.

‘Now,’ said Imogen, jumping down from the bed, ‘stand aside.’

The boy’s face fell. ‘Shan’t,’ he said, sounding a little less certain than before.

The sisters advanced. Marie was slashing at the air in a way that made Imogen nervous. ‘All right, Marie, rein it in,’ she hissed.

‘I’m not doing it on purpose,’ said her sister. ‘It’s really heavy.’

The boy’s eyes followed the blade. ‘You can’t go!’ he said, standing his ground. ‘Not until after dinner! It isn’t fair!’ At the last moment, he lost his nerve and dived to the right, leaving the door exposed.

Marie dropped the sword. Imogen opened the door and hurtled down the spiral staircase. ‘Come on!’ she called to her sister. ‘Follow me!’ But she didn’t get very far. She collided with a figure who was coming up the stairs. She stumbled back into the boy’s room, tripping and landing on top of Marie.

‘What’s this?’ said the figure. ‘A pair of peasants come to steal from His Royal Highness?’

‘We didn’t steal nothing!’ said Marie passionately.

‘Anything,’ corrected her sister.

‘Is that so?’ said the figure, stepping into the light.

An ancient man in a black robe stood wheezing in the doorway. His face was shrivelled and deathly white. He looked like a creature that had lived under a rock for too long. When he’d caught his breath, he pointed at Imogen and Marie.

‘We’ll let the king decide what to do with you two,’ he said.

‘Oh, Yeedarsh, it’s you!’ said the boy.

‘At your service,’ said the old man, giving a shaky bow. ‘I caught these thieves escaping down the staircase. I’ll get them taken to the dungeons, Your Majesty. Don’t you worry. We’ll find out how they broke in.’

Marie hid behind Imogen and Imogen turned to the boy. ‘We’re not thieves,’ she said. ‘Go on – tell him.’

The boy folded his arms and looked out of the window so Imogen couldn’t see his face.

‘Oh, we’ve got plenty like you down in the Hladomorna Pits,’ said Yeedarsh, and his mouth curled into a nasty smile. ‘Plenty who say they didn’t do it. But they always come clean in the end.’ He wet his lips, eyes darting between the boy and the two girls. ‘Don’t they, Your Highness?’

‘Um … yes. They do.’

‘I’ll get the Royal Guards,’ said Yeedarsh. ‘They’ll be no more trouble for you. Or perhaps we could just throw them out the window? Save ourselves the bother?’

The boy glanced around as if unsure what to say.

‘That’s what we used to do when we were short of room in the Pits,’ continued the servant. ‘Your grandfather never regretted tossing his enemies out of the window. Apart from that one who landed in a pile of manure. Hopped off with nothing but a sprained ankle—’

‘Yeedarsh, you’re getting carried away,’ said the boy.

‘Well, what do you want to do with them?’

There was a long pause.

‘What time’s tea?’ asked Imogen.

‘What’s that got to do with anything?’ snapped Yeedarsh, scrunching up his face so it looked like an old tissue.

‘We were going to stay for tea,’ she said quietly. The boy didn’t turn round. Imogen held her breath.

‘Pah! Thieving peasants for dinner?’ croaked Yeedarsh. ‘Our prince would rather dine alone than with the likes of you. Isn’t that right, Your Highness?’

‘Dine … alone?’ said the boy.

‘Yes. As you always do, Your Majesty.’

‘Why would I do that when I have guests?’ He nodded at Imogen and Marie.

‘Guests? You mean to say you invited these … people into the castle?’

‘Yes.’

‘But why? Does the king know? He ought to know.’

‘Just leave it with me, Yeedarsh,’ said the boy.

Yeedarsh was visibly perplexed. He kept making as if to leave and then coming back, opening his mouth and then closing it again.

‘We’ll be wanting breakfast for three,’ said the boy. ‘Tell the kitchens.’

‘Er … very good,’ said the old servant. ‘But, if any of the silver cutlery goes missing, your uncle will have their heads. I’ll be counting the spoons …’

After breakfast, Imogen and Marie were given clear instructions on how to spend the hours before dinner. The boy said they were to play around the castle, but they mustn’t venture outside. They should return to the room at the top of the second tallest tower when the bells sounded at dusk.

The castle was so big and sprawling that the girls had no problem avoiding grown-ups. There hardly seemed to be anyone around. Instead of people, the castle was populated by strange and beautiful objects. Some rooms housed a few decorative items; others were so full that you could hardly open the door.

In one room, there was a large group of ferocious-looking warriors. At first, Imogen was terrified, but she soon realised that they were just suits of armour.

Marie tried on a helmet. ‘We’d better not be asked to eat anything with its face left on,’ she said. The helmet covered her eyes and nose, but her mouth continued to talk: ‘If he serves fish, I’m out of here.’

Another room was entirely dedicated to paperweights. There were paperweights of blown glass and paperweights of metal. There was even a wooden one carved into the shape of a bear. The room had a large window that overlooked the square that the girls had run across the night before.

‘There are the city walls,’ said Marie, ‘and the meadows we walked through to get here.’ Imogen joined her at the window.

Beyond the meadows there were forests and mountains. They seemed to enclose the valley, leaving no way out. The forests were dark and deep and the mountaintops were as sharp as arrowheads. Some of the trees were already turning gold, which was strange because at home it had been the start of the summer holidays.

‘Imogen, how are we going to find the door among all those trees?’

‘It’s not going to be easy,’ conceded Imogen. ‘We could go now, try to retrace our steps.’

‘What … not stay for tea?’

‘That boy isn’t going to stop us. He wouldn’t even know we’d gone until it was too late. He said he has his own affairs to attend to.’

‘But we promised we’d stay for tea,’ said Marie.

‘I don’t remember promising anything.’

Marie pressed her lips together in the way that she did when she was thinking. ‘What if the monsters are still out there?’ she asked.

Imogen looked down at the square where some kind of market was taking place. It didn’t seem as if there were any monsters, but she could still remember that terrible screeching and the fear of being chased. A shiver ran down her spine.

‘Perhaps it is worth staying for tea,’ she said. ‘Perhaps, if we play the boy’s little game, he’ll help us get home. He might even know how to make the door in the tree open.’

‘Yes, that’s a good idea,’ said Marie, brightening. ‘With a bit of help from someone who lives here, we’ll be back with Mum in no time.’

Imogen nodded. There was a thought buried so deep in her mind that she was barely aware of it, but it was there all the same: the castle was interesting, and so was the city, especially now there were no monsters. Maybe it wouldn’t be such a bad thing if Mum had to wait for them to come home. Maybe it was only fair.

After all, if Mum could go off with her ‘friends’, leaving Imogen behind, then Imogen could do just the same.

Prince Miroslav – whom Imogen thought of as the boy – never told his guests exactly how he spent that day.

He didn’t tell them that he’d been frantically making arrangements for the evening: instructing cooks, sending servants on errands. He wanted it to appear normal. He wanted the girls to think he had guests for dinner every week.

He certainly never told them how his belly squirmed as he approached his uncle’s study. Two guards stood to attention on either side of the entrance. ‘Is King Drakomor in?’ Miroslav asked.

‘Yes, Your Majesty.’

He struggled with the heavy door, prising it open just wide enough to squeeze through.

The king had shut the sun out of the room, but it wasn’t to protect delicate parchment. There were very few books in this study. Instead, the shelves held golden trinkets, rare ornaments and precious stones.

The study was becoming increasingly crowded. Prince Miroslav had to suck in his tummy so he could fit past an enormous painted vase. That was a new one.

The king magpie, collector of it all, sat at his desk in the centre of the room.

One jewel, mounted on a marble base, stood taller than Miroslav. As he walked behind it, his figure turned orange.

‘Miroslav, is that you?’

Miroslav froze like an insect in amber. ‘Yes, Uncle.’

‘Don’t skulk. I can’t bear skulkers. Especially not among my collection.’

Miroslav peeped out from behind the jewel. ‘Sorry, Uncle,’ he said.

‘You didn’t touch that vase, did you?’

‘No.’

‘Good. It’s five hundred years old, from the Nerozbitny Dynasty. The only one of its kind.’

Miroslav didn’t know how to respond to that information.

King Drakomor was busy at his desk, cleaning a necklace with a tiny brush. He was wearing a single glass lens, so that, when he turned to Miroslav, it was with a blinking, oversized eye.

He didn’t look like his nephew. His nose was smaller, straighter. He was fair-skinned with grey, close-set eyes, and he wore his hair parted to the side, as was the fashion. Miroslav sometimes wondered if his uncle would love him more if they looked alike.

‘Why are you here?’ said the king, putting down the necklace. Miroslav’s heart beat fast in his chest. What if the old servant, Yeedarsh, had got here first? What if he’d told Miroslav’s uncle to send the girls to the dungeons?

‘Out with it,’ said the king, and he drummed his fingers on the table so his rings tapped against each other.

‘You know how I don’t have a tutor at the moment,’ said Miroslav.

‘How could I forget? Yeedarsh never shuts up about it.’

‘Well, I was wondering if, in the meantime, perhaps I might have some other children to play with?’

The king raised an eyebrow, sending the glass lens tumbling to the desk. ‘What other children?’ he said.

‘Oh, just a few friends.’

‘You don’t have any friends.’ The king didn’t say this unkindly, but in a matter-of-fact way. Still, Miroslav flinched.

‘They’re just a couple of peasants I met when I was visiting the market,’ he said. ‘No one important.’

‘Peasants? I don’t want them stealing my collection,’ said the king. ‘And I don’t want you picking up their dirty habits.’

‘I won’t.’

‘And I certainly don’t want you getting in my way. I’m expecting some guests of my own. I can’t have a load of children running around.’

‘You won’t see us, I promise. You won’t even know we’re here.’

‘Hm.’ The king stroked his moustache.

‘Please, Uncle,’ said Miroslav.

King Drakomor put the glass lens back in his eye and continued to polish the necklace. He didn’t look up as he spoke: ‘All right, boy. You can keep them. But, if I so much as smell a child over the next few days, your little friends will be thrown out after dark, to be killed by the skret. Do we understand each other?’