Полная версия

A Clock of Stars: The Shadow Moth

Imogen climbed up the roots and spread her arms out wide, placing her left foot on the trunk, then her right foot. Woodlice ran for cover as she disturbed their rotten paradise. She made her way across the dead tree slowly, hardly daring to breathe in case it affected her balance.

The last part of the tree was slippery so Imogen lowered herself on to her belly. She wriggled forward, rubbing dirt into her top. When the trunk was above earth instead of water, Imogen rolled off and landed on her feet. She smiled, pleased with herself, and continued on her way.

The plants on this side of the river had won the war against the gardeners. They had no interest in looking how people wanted them to look. Oversized shrubs had thorny throats. Wayward flowers bobbed their heads as Imogen swept by and the further she went into the Haberdash Gardens, the more she got the feeling that she wasn’t welcome.

She heard a noise from somewhere behind, like the patter of feet. She turned. There was no one there.

Imogen did think about going back to the tea rooms, but she was sure that the moth was trying to show her something and she wanted to see what it was. A large drop of water landed on her forehead and she glanced up at the sky. Another drop splashed on her cheek and then the rain poured down. The moth flew faster. Imogen ran to keep up. Again, there was a sound behind her, but she couldn’t turn back. She wouldn’t turn back. She sprinted as fast as she could. Mud splattered up her legs.

The shadow moth led Imogen to an enormous tree. The highest branches seemed to touch the clouds and, under the jabbering of the rain, Imogen was sure she could hear roots drawing up water from the depths of the earth.

She stepped under the tree’s canopy and put her hand on the rough trunk. The moth landed next to her fingers and moved its antennae in circles. In this light, it looked more grey than silver, camouflaged against the bark.

Imogen couldn’t wait to tell Marie what she’d found: the biggest tree in the world. Marie would be amazed (and perhaps a little bit jealous).

The moth crawled away from Imogen’s hand and she followed its progress. Soon it wasn’t walking on gnarled bark, but smooth wood. Imogen ran her finger over this new texture. She knew what it was. She stepped back a few paces. Yes, it was as she’d thought.

There was a door in the tree.

The door was smaller than most. A grown-up would have to stoop to fit through, but for Imogen it was just the right height.

She wondered what was on the other side. Perhaps the tree was a hiding place for treasure; the kind of treasure Mrs H might forget she’d got hidden.

The moth crawled down the door and stopped at the keyhole. Imogen knelt next to it, grinding more soil into her jeans, and peeped through. All she could see on the other side was darkness. She pulled back.

‘Is this what you wanted to show me?’ she asked.

The moth folded back its wings and wriggled through the keyhole.

‘I think that’s a yes,’ said Imogen. She stood up, pulled open the door and stepped through.

At first, it was very dark. Then, as Imogen’s eyes adjusted, towering shapes swam out of the gloom. A few seconds later, she realised that they were trees. She was standing alone in a forest just before sunset. Branches shredded the low-lit sky into ribbons.

Imogen’s head filled with questions. How could a forest fit inside a tree? Why wasn’t it raining here? How come it was so dark and quiet? It was as though the forest had been smothered by a giant duvet.

Imogen looked back at the door and realised that she hadn’t imagined the noises behind her. She really had been followed. There, just stepping over the threshold, was her sister.

The light from the gardens shone round Marie. Her hair had turned dark in the rain, her clothes were covered in mud and her eyes were wide. She pushed the door closed behind her. The hinges must have been well oiled because it moved easily, clicking as it shut. The sisters’ eyes met.

‘Marie!’ cried Imogen. ‘What are you doing here?’

For a split second, Marie looked afraid – caught off guard – but she quickly regained self-control.

‘What am I doing here?’ she said. ‘I could ask you the same thing.’

‘So it was you following me,’ said Imogen, folding her arms.

‘You’re not allowed in the Haberdash Gardens.’

‘Neither are you,’ said Imogen. ‘Can’t you let me do anything on my own?’

‘I’m going to tell Grandma. You’re doing trespassing.’

Imogen scowled. It was her moth, her garden and her secret door. Marie hadn’t even been invited; she’d hijacked Imogen’s adventure and now she was threatening to destroy it. Imogen wanted to throw something at her sister. She wanted to pull her ponytail. No, she wanted to make her disappear.

‘Go on, then. Go and cry to Grandma.’

‘Fine! I will!’ Marie turned and grabbed the door handle. Then she glanced over her shoulder.

‘Well, what are you waiting for?’ demanded Imogen.

‘It won’t open,’ said Marie.

‘Move out of the way.’

Imogen tried the handle, but the door wouldn’t budge. ‘Oh, well done!’ she shouted.

‘I didn’t know it locked itself!’ squealed Marie.

‘You stupid baby. If you’re not sure what something does, leave it alone!’

‘You shouldn’t have opened it in the first place,’ said Marie.

‘You should have stayed at home where you can’t spoil everything!’

Imogen felt panic rising in her chest. She kicked the door and hammered with her fists, but it wouldn’t open.

The shadow moth she’d followed was nowhere to be seen.

Marie looked like she might cry and Imogen knew it was up to her to get them out of this mess. She also knew that they couldn’t stay put. It was much colder here than it had been in the Haberdash Gardens and she was already shivering in her damp clothes.

‘We need to get moving,’ she said, turning on her heel like a general.

‘Do you think we’ll be back in time for tea?’ asked Marie, with a wobble in her voice.

Imogen thought that was unlikely. It didn’t feel like they were in the gardens any more. It was as if they were in a different place altogether, but she couldn’t stand it when Marie cried so she murmured something reassuring about how Grandma would be out looking for them.

Above, the first stars began to stir. They winked at each other and looked down at the girls walking through the forest, tiny among the trees. A person who knew how to read the stars might have said they were smiling.

Imogen didn’t tell Marie, but she was secretly relieved that she wasn’t alone in this strange place. It was hard to see and she kept tripping over roots and snagging her jeans on brambles. She strained her eyes, hoping to catch the flutter of wings in the darkness, but her moth had gone.

Every so often, Imogen heard the whisper of her worry creatures. Lost in the forest, they hissed. Lost in the forest and so far from home.

Imogen walked faster.

‘Hey, I can’t keep up,’ moaned Marie.

Imogen looked over her shoulder. The worry creatures were scurrying from tree to tree, but they fed off her fears, not her sister’s, and Marie couldn’t see them.

‘Come on,’ said Imogen. ‘I want to get out of this wood.’

As the girls walked, the trees grew further apart, and something caught Imogen’s attention. Something that wasn’t a worry creature. ‘Hey, Marie, can you see that?’

‘It’s one of those bugs with a light in its bum,’ said Marie.

‘A glow-worm? No. It’s bigger than that. And further away.’

‘Maybe it’s Grandma! Out with a torch!’

Imogen steered Marie towards the light. It was too low to be a star – it was too still to be Grandma – and yet it lured her on. There was something reassuring about the soft glow. Imogen wanted to be there, among other people. That was what light meant: life, warmth, a flicker of hope, a toasted teacake and a short drive home.

The girls came to the edge of the forest and Imogen’s heart sank. They were standing in a valley surrounded by huge looming shapes that looked like mountains. Imogen couldn’t see what was at the bottom of the valley, but the light she’d been following was there. She guessed it was two miles away. Maybe three. All of Imogen’s teacake-shaped dreams vanished. This place was vast and foreign and full of shadows. There would be no easy way home.

This was the part where a grown-up was supposed to turn on the lights, fold away the forest and send the girls off to bed. But there were no grown-ups and the forest was real. Imogen wanted to cry.

‘That doesn’t look like the tea rooms,’ said Marie.

Imogen bit her lip. Blubbing wouldn’t help.

‘What are we going to do?’ said Marie. ‘I’m cold. I want to go home.’

Imogen’s pent-up tears turned to rage. ‘I don’t know the way,’ she snapped. ‘Someone slammed the door, remember?’

‘It was a mistake!’ shouted Marie. Her words echoed round the valley and she jumped behind her sister, spooked by the ghosts of her own voice. ‘Anyway, I didn’t slam it. I gave it a gentle push.’

‘Oh good, well, that’s fine, then,’ said Imogen.

For a moment, neither of them spoke. Then Imogen took a deep breath. ‘Look,’ she said. ‘Look at that light. There must be people there who can help us get home.’

‘Do you think so?’ said Marie.

‘I’m sure of it,’ said Imogen.

Together they walked towards the light at the bottom of the valley.

Marie held Imogen’s hand. Imogen didn’t stop her.

PART 2

The two sisters walked through meadows and hopped across brooks.

The moon was a sliver, but it seemed to be larger than usual and, with no branches overhead, there was just enough light for Imogen to see where she was putting her feet. In some places, the grass was cropped close to the ground; in others, it grew long and wild. Field mushrooms gathered in circles, as though assembled for a night-time dance.

‘Do you think Mum’s having a good time with Mark?’ asked Marie.

‘I hope not. I didn’t like him,’ said Imogen, making an extra effort to trample the grass. ‘I don’t know why she bothers with boyfriends. She’s got us, hasn’t she?’

‘Yes … but he might be nice.’

‘I doubt it,’ said Imogen. ‘He was wearing stupid shoes. He was saying stupid things. I bet it’ll go wrong, just like it did with the other boyfriends.’

‘Grandma says you can tell a lot about someone from their shoes.’

‘Grandma’s right,’ said Imogen, ‘and Mark’s shoes were stupid.’

‘I wish Grandma was here right now,’ said Marie.

Imogen led the way through the meadows until they stood at the foot of an enormous wall. Behind the wall she could see the shadowy outlines of tall buildings. ‘Wow!’ whispered Marie. The wall was three times higher than a house and each stone was as large as a car.

‘There must have been some big battles in the olden days,’ said Imogen, ‘to need a wall like that.’

‘How do we get past it?’ asked Marie. ‘The light’s on the other side.’

‘I think there’s a gate. It’s hard to make out, but look over—’ Imogen was interrupted by a bell. The sound was deafening. More bells joined the din. She clapped her hands over her ears.

Marie was hopping up and down and yelling, but Imogen couldn’t hear what she was saying. Marie pointed at the gate. It had started to lower.

Imogen ran and Marie followed. The bells continued to toll. The stars flickered with excitement and even the crescent moon was unable to tear his gaze from the two silhouettes dashing towards the gap between the ground and the lowering gate.

As the bells struck their final note, Imogen threw herself on to all fours and crawled through. ‘That was close!’ she gasped, getting to her feet, but when she turned round Marie wasn’t there. Her hoodie was caught on the spikes that ran along the bottom of the gate. She was centimetres away from being skewered.

‘Help!’ she shrieked, trying to claw her way forward. ‘Imogen, I’m stuck!’

Imogen ripped Marie’s hoodie free and grabbed her by the wrists, dragging her through on her belly. The gate hit the ground. Imogen collapsed. They’d made it.

‘I – I almost got squished to death,’ said Marie, breathing hard. ‘Imagine what Mum would have said if I’d got squished to death.’

‘Bet I’d have been the one in trouble,’ muttered Imogen.

‘Maybe,’ said Marie in a small voice. ‘But … um … thanks for saving me.’

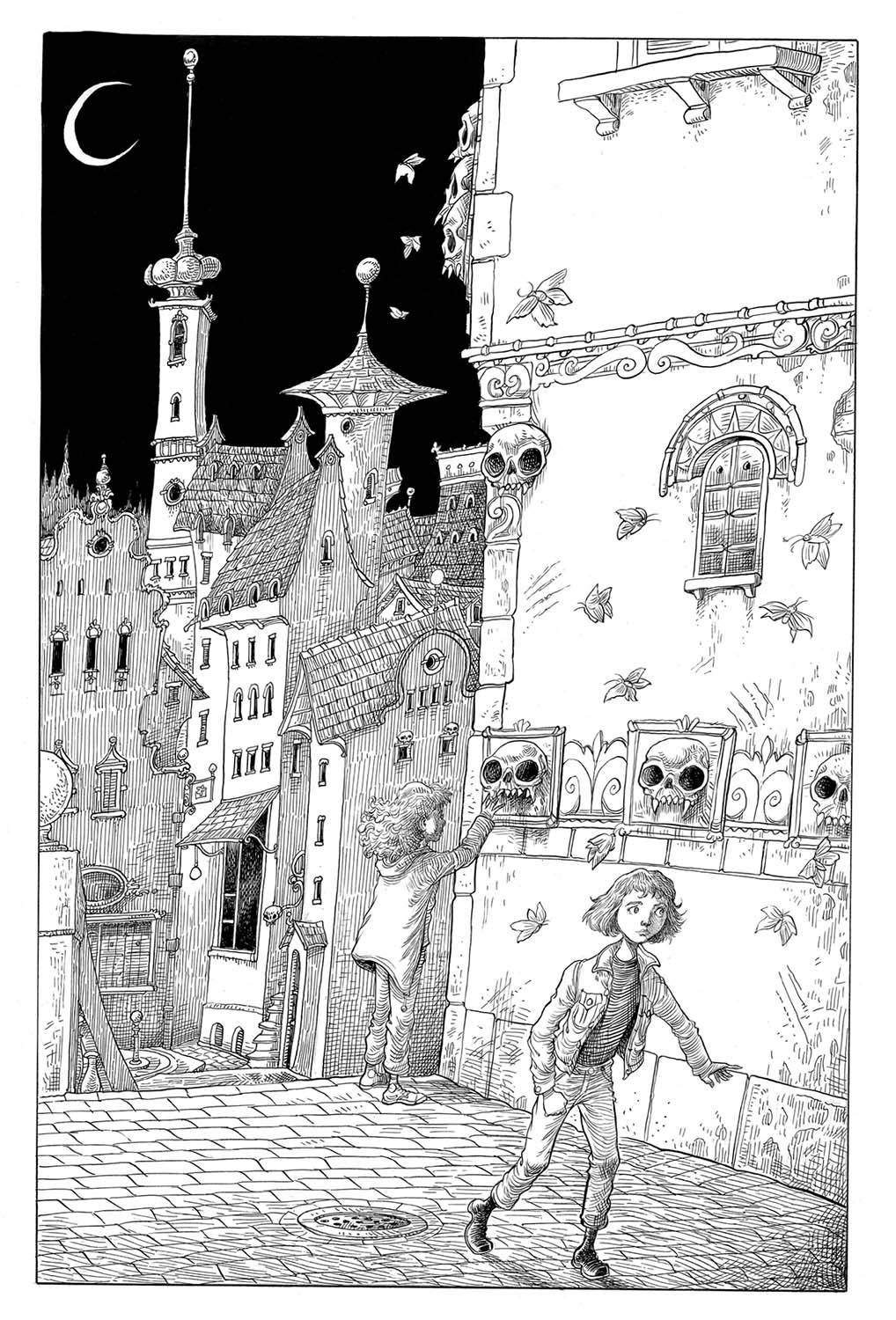

When Imogen had recovered, she helped Marie to her feet and looked around. On this side of the wall, there was a city with painted houses and tiled roofs and pointy towers. Some of the buildings were decorated so delicately that they reminded Imogen of the birthday cakes Mum made – all frosted flowers and piped icing.

The girls walked through the city streets towards the light. There were no people. Instead, the place had been given over to the dead – or what was left of them. Thigh bones dangled from windows like crooked wind chimes. Strings of vertebrae decorated doors. Strangely shaped skulls poked out between stones.

Imogen felt vaguely sick. She wasn’t sure what was more alarming: the not-quite-human dead things or the thought of what might have killed them.

‘Whose skulls do you think they are?’ asked Marie.

‘How do you expect me to know?’ said Imogen, who didn’t want to have this conversation.

‘They’re very small. Do you think they belonged to children?’

‘No.’

‘And look what a lot of teeth they have …’

‘Come on, Marie. We have to keep walking.’

Imogen took a deep breath and relocated the light. It looked like it was coming from the heart of the city. That was the way to go.

Every building the girls walked by was shut up. There was no light seeping between the shutters. No smoke from the chimneys. Instead of welcoming words, they were greeted by skeleton smiles.

The only things that seemed to be alive were the moths that were flying in every direction. They were small and shimmering. They were large with speckled wings. They were blue like midnight or pink like the dawn. Imogen kept looking for her moth – the one that had shown her the door – but it was nowhere to be seen. These were just normal insects. They weren’t going to show her the way home.

Imogen and Marie crossed a bridge that was guarded by thirty black statues. Imogen counted them as she went. Counting things usually made her feel better, but this time it didn’t work.

The statues were all stern-looking men. Someone hadn’t agreed with the sculptor about how many limbs they ought to have. Arms had been amputated. Legs were sliced off at the knee. A few heads were missing and the stonework was covered in scratches.

The deeper the girls walked into the city, the taller the houses grew, rising from hunched cottages to proud, five-storey mansions. A grand house had skulls embedded in its walls. Marie paused to examine one. ‘Hey, Imogen, come and see this.’

Imogen didn’t like the look of the skull. Not only did it have a lot of teeth, but they were pointed, almost triangular. ‘We’ve fallen into a nightmare,’ she muttered. ‘I think we should keep moving.’

‘Just one second,’ said Marie, and she moved closer to the skull so that the eye sockets stared down at her upturned face. She stretched out her hand, reaching into the gaping jaw. Her fingertip hovered above a fang, nearly touching the point. Then she jumped, startled by a terrible scream. Imogen jumped too.

‘What was that?’ cried Marie, whipping back her hand.

‘I don’t think we want to find out,’ said Imogen. ‘Time to go!’

The girls rushed through the streets. Fear gave them energy. That scream had sounded wild and furious and it had come from somewhere near the city walls.

Imogen tried to focus on the light, to navigate towards it, but with every wrong turn her heart beat faster. Suddenly even the buildings seemed hostile, with their slanting window-eyes.

Another screech. Louder, closer.

Imogen banged on the door of a house. Moths flew out from between the shutters, but no one came to help.

Imogen kicked the door and cursed the shadow moth. She cursed her rotten luck too. She promised God, the moon, whoever was listening, that she wouldn’t run away again. She’d eat liver and broccoli. She’d share her stuff with Marie. Just let them be back home, tucked up in their beds.

More screams. ‘They’re coming this way!’ cried Marie.

‘Follow me,’ said Imogen.

She swung round the corner, half expecting a dead end, but instead the girls found themselves in a large square. There was a dark castle at the far side, crowned with towers and turrets. Light shone from the top of a tall tower. ‘That’s it,’ said Imogen. ‘That’s where the people must live.’

Imogen and Marie sprinted across the square and pounded on the castle door.

‘Let us in! Let us in!’

There was no response so they hammered harder. The shrieks were closing in – the monsters would be in the square any second – but the castle door remained locked.

There was nowhere to go.

‘Oi! You two – over here!’ A boy’s face poked out from a little door that was cut into the larger entrance.

Imogen and Marie didn’t hesitate. They ran over, the boy opened the door wider and the girls fell inside. He pulled the door closed, shutting out the starlight and monsters. Keys jangled in the dark.

‘They won’t get through that,’ he said, and a candle illuminated his face. He had far-apart eyes, dark olive skin and a mop of curly brown hair that couldn’t quite hide his sticky-out ears.

He pressed an ear to the door and the girls did the same. Claws scratched on cobbles. The boy put his finger to his lips. The shrieking creatures, whatever they were, were very close. Imogen held her breath. The door rattled. The children jumped back and Marie let out a whimper.

Outside, the monsters were screaming to be let in. ‘They won’t get past the door,’ whispered the boy. ‘They never do.’

Sure enough, after a few minutes, the noise receded. The children stood still for one minute more, not daring to move until the shrieks had faded away.

‘Right,’ said the boy, putting down his candle. ‘First things first.’

Imogen wiped her hand on her jeans in preparation for a handshake.

‘Face the wall and put your hands on your head.’

‘What?’

‘You heard me,’ said the boy. ‘Turn round and put your hands up.’

Reluctantly, Imogen did as she was told. The boy searched inside the top of her socks. Then he turned her pockets inside out.

‘What are you doing?’ said Imogen.

‘Checking for weapons,’ said the boy.

‘Why don’t you just ask?’

‘Peasants can’t be trusted. Besides, if you’d come to kill me, you’d never hand over your knives willingly.’

Imogen had never been called a peasant before. She looked down at her mud-streaked clothing. Perhaps he had a point, but still it was hardly polite.

‘You’re all clear,’ said the boy. ‘Stand aside.’ Next he searched Marie. He lifted up her ponytail with great suspicion, and gave it a shake as if expecting a dagger to fall out.

Imogen watched him. She guessed he was about her age, perhaps a little older. He was dressed very strangely, in an embroidered jacket that looked like it was made out of fancy curtains. He wore rings on almost every finger.

‘We’re not peasants,’ she said, but the boy wasn’t listening. He was going through Marie’s pockets and he’d found something. He held it between his thumb and index finger, inspecting it in the candlelight.

Imogen saw the shiny surface and she knew what it was. ‘That’s my stone,’ she said. Marie must have had it in her pocket since their fight.

Marie lowered her hands and turned round, guilt written all over her face.

The boy continued to study the fool’s gold so Imogen said it again. ‘That’s mine. That’s from my rock collection.’

‘What’s a peasant doing with a precious stone?’

Imogen could feel that familiar quickening of her pulse, but she spoke each word slowly. ‘Give. It. Back. I am not a peasant.’

Marie looked from her big sister to the boy and back to her big sister. ‘Sorry, Imogen … I was going to give the treasure back eventually, I promise. I just wanted to borrow it …’

Imogen advanced on the boy. ‘Give me my gold, you thief.’

‘Who are you to call me a thief?’ he sneered. ‘This is my kingdom and so is everything in it – including you, your friend and your so-called treasure.’

That was the last straw. Imogen pounced. She knocked the fool’s gold out of the boy’s hand and pushed him to the floor. Marie caught the stone. Imogen and the boy were a tumbling mess of arms and legs. His elbow clipped her chin, making her jaw bang shut. She retaliated with a knee to his stomach.

‘Ow! You filthy urchin! Get off me!’

‘Marie,’ cried Imogen, ‘grab his arms!’

Marie shoved the stone back into her pocket and went for the boy’s wrists. She caught one. Imogen trapped the other hand with her foot, making the boy cry out. The rest of him thrashed wildly. ‘Help me!’ he shouted. ‘Somebody help! They’re trying to kill me!’

Imogen kicked the shoe from her other foot, whipped off her sock and stuffed it into his mouth. She pulled the scrunchie from Marie’s hair and wrapped it round the boy’s wrists, handing control to Marie. That freed up Imogen to grab his ankles. The boy stopped wriggling.

‘Hah! So you know when you’re beaten, then?’ crowed Imogen.

‘He looks kind of angry,’ said Marie. ‘His face is going red.’

‘Well, that’s tough, isn’t it? He shouldn’t take other people’s things.’

‘Is someone squeezing your head?’ cooed Marie to the boy, enjoying her position of power a little too much.

Imogen paused. ‘Wait. What do you mean his face is going red?’ She couldn’t see him properly from her position at his feet.

‘He looks like a beetroot …’ said Marie.

‘The sock!’ cried Imogen.

‘Ooh, look how his eyes are bulging! He’s really very cross.’

‘Marie, the sock! Take the sock out his mouth!’

Marie obeyed. The boy inhaled and Imogen let go of his ankles. The sisters were silent for a moment while the boy rolled on to all fours, spluttering and gasping.

‘Why, I ought – I ought to set the Royal Guards on you!’ He struggled to his feet. ‘I ought to have you both beheaded! I ought to have you chopped up and fed to my fish. I—’

‘That’s enough,’ interrupted Imogen in as kind a voice as she could manage. ‘We didn’t mean to choke you.’ She pulled the scrunchie off his wrists and handed it back to Marie.