Полная версия

Casting Shadows

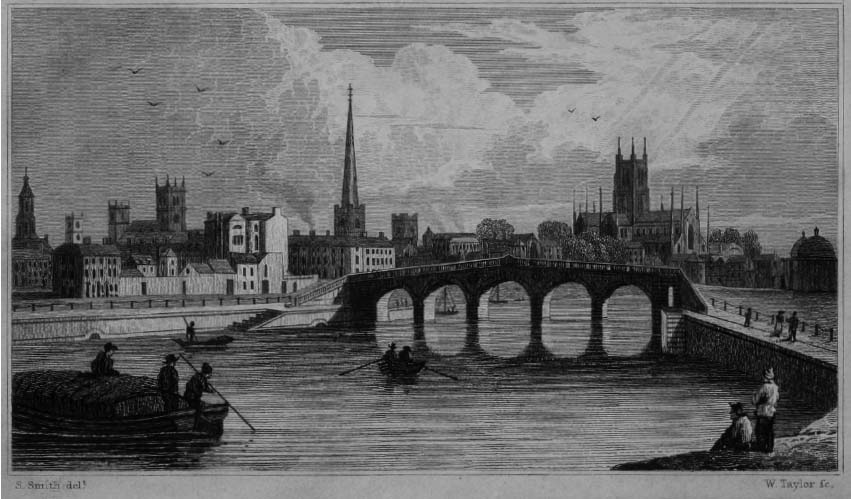

Worcester and its cathedral viewed from the Severn, 1829

A Concise History and Description of the City and Cathedral of Worcester, printed by T. Eaton in Worcester, 1829. Sourced from Archive.org, The Library of Congress

By the time I reached Grimley I had used up more of my day than I had allowed for, and had been forced to cycle much harder than I like to. I was hot and bothered and Grimley’s charms were not of an order to soothe my savage breast – not immediately, anyway. It retains the name it had in Prior More’s day, but precious little else. It straggles pleasantly enough along a minor road off the A443, with the Severn curving its leisurely way beyond the fields to the east, but there is nothing at all distinctive about it. The church was restored beyond recognition in the nineteenth century, and the manor house on which More lavished so much attention and spending disappeared long ago.

As for his fishponds – his ‘parke poole at grymley … ye mere at grymley … ye myddul poole in ye parke at grymley … ye stanke … ye fur poole at grymley … ye utter poole in grymley parke … ye stewe at grymley …’ – they are not easy to locate and still harder to match to his references. According to the scheduling by Historic England, the three main ponds were elongated, narrow rectangles aligned north/south along the backs of what are now the gardens and paddocks of the houses on the east side of the road through Grimley. They are a lot easier to spot from Google Maps than they are from the ground, as they are concealed within thickets of alder and willow and undergrowth and behind barriers of reeds. But I did eventually fight my way through the vegetation and over a fence and was rewarded by glimpses of muddy banks and open water, although it was no more than a few inches deep. A definite pond, nonetheless.

When the ponds were being dug, the land around was organised in blocks of medieval ridge-and-furrow fields. Now it is all ploughed and made productive in the modern way, but the ponds and their immediate surroundings have been left to their own devices behind barbed wire, presumably because the ground is too marshy and clayey to be worth reclaiming. All that engineering – the dams and embankments, the leats, the sluices, the channels that fed the ponds from a spring to the north – has been taken back into the earth and swallowed up. But it is consoling that the whole intricate system and the mark it made have not been entirely erased.

Prior More was evidently an attentive son to his parents. When his father died at Grimley in February 1520, William ordered three hundred herrings, three salt fish and four salmon (two-and-sixpence on their own) for the funeral feast. His mother followed the next year, her passing marked by the singing of dirges in the cathedral (three-and-fourpence) and in Grimley church (one shilling). Her funeral breakfast included mutton, beef, pork and six geese, abundant bread and ale, and a great deal else. Fourpence was paid to ‘Rd. Sawyer for dygging of ye pit in ye chauncel’.

Having found water in Grimley, it was time to head for another of Prior More’s fishpond projects, at Battenhall on the southern fringe of Worcester. The complex is located in a shallow trough of agricultural land bounded to the east and south by the A4440 and on its other sides by the surburbs of Red Hill, Battenhall and St Peter’s. As at Grimley, the manor house is no more, but its site – immediately to the north of the ponds – is occupied by Middle Battenhall Farm, a mainly seventeenth-century farmhouse with outbuildings now converted into very smart residences. The fishponds, three of them, are rough grazing although the layout and embankments and the old ridge-and-furrow fields around are fairly easy to discern.

Judging by the amount of time he spent there, Prior More seems to have preferred Battenhall to Grimley. He kept an ‘ambling grey mare’ there and recorded the arrival of her foals. He kept an eye on the swannery – ‘upon seynt Dunstan’s daye the swannes at Batnall browt forth four cynets in to ye poole’. He had the bedchambers hung with rich painted cloths, installed a new stained-glass window, hired bears for baiting and jugglers to provide amusement at dinner, and generally entertained in a manner befitting a country squire of exceptionally ample means.

Then there were the ponds – ‘ye mot … ye nether poole … ye dey poole … ye over parke poole’ and so on. He spent consistently and considerably on their construction and maintenance – ‘item ye clansynge of ye pool at Batnall with carage besides mete and drynke 102s 7d … item to John Kervar his man and 2 sawyers at batnal for making ye flud leat 3s 3d’. In summer the ponds were stocked with eels, presumably caught from the Severn where there were plenty. Tench were the next most popular species, with more modest numbers of bream, roach and small pike, which were stocked in winter.

Owing to more inept map-reading, it took me some time to locate Prior More’s handiwork at Battenhall. By the time I had finished wandering around the somewhat unexciting mounds and dips and inspecting the overgrown trickle that fed the system, the afternoon was well advanced and I realised that I was not going to get to the prior’s third country residence at Crowle, which is a few miles east of Worcester and would become the chosen place of his retirement.

Unlike me, William travelled in style, with a retinue of four gentlemen, ten yeomen, ten grooms, chaplain, steward and assorted lowly servants. Crowle was another moated manor house, originally built in the thirteenth century and substantially extended and refurbished for the comfort of the prior. His journal shows that over the years he spent heavily on it and its water features. The house – with its chapel, dining-hall, great kitchen and spacious chambers – was decorated with all manner of hanging cloths. The chambers were fitted with feather beds and the down pillows were covered in satin. Everything was itemised from the ‘18 platers … pottygers … sawcers’ in the kitchen to the ‘candilstycks and dashell’[fn1] in the chapel.

Outside, the moat was by 1533 ‘perfett made and fynyshed upon seynt Luke’s day … whych mote cost in ye hoole charge £8 19s 3d’. The following spring it was stocked with ‘18 tenches’ and ‘46 store breams’, with more to follow. Everything – including the pigeon-house, the tithe barn and the smaller ponds – was made ready for Prior More’s retirement from what had been a busy if not conspicuously holy working life.

But he nearly came unstuck. His success in life had not come without arousing envy, and he had made his enemies. Besides that, politics and the great divorce struggle between Henry VIII and Rome were sending waves out even as far away as Worcester. Complaints were made about More’s lavish spending, favouritism, accounting methods and ostentatious extravagance. He was accused of diverting alms intended for the poor to his own servants. There is a tantalising reference in a letter to Thomas Cromwell from Hugh Latimer (appointed Bishop of Worcester in 1535 and later burned at the stake) to a ‘great crime’ of More’s – that of permitting one of his monks ‘to use treasonable language about the king’s divorce and the character of Anne Boleyn’.

The downfall of Wolsey, the break with Rome, and finally the appointment of Cromwell as Visitor-General of religious houses, combined with the mutterings against him from within his own power base, persuaded the canny prior that it was time to slip away from the main stage. He took advantage of the lenient terms being offered to the ‘heads of houses’ who acquiesced in their own dissolution to negotiate favourable terms for his retirement.

More was given the use of Crowle for his lifetime with a pension of £50 a year, plus a lodging in Worcester ‘with wood and fuel sufficient’. His debts of £100 were paid off and he was presented with silver cups, spoons and goblets as well as sheets, tablecloths, napkins and everything else he might require. In 1535 he took himself quietly off to Crowle, at which point his journal falls silent.

The destruction and upheaval that saw Prior More quit the scene and poor Abbot Whiting of Glastonbury hanged, disembowelled and dismembered were the cause of much satisfaction and advantage to others. Among them was that energetic henchman of Cromwell and instrument of Henry VIII’s capricious will, Thomas Wriothesley, later Sir Thomas, later still the 1st Earl of Southampton.

As a reward for his assiduous work ‘in the King’s great business’ and in the pulling down of shrines and images and in sundry other matters, Wriothesley received some of the choicest monastic estates available – including Quarr Abbey on the Isle of Wight, Hyde Abbey near Winchester, Beaulieu Abbey on the west side of the Solent, and Titchfield Abbey on the east side.

Thomas Wriothesley (1505–1550), 1st Earl of Southampton, painted by Hans Holbein the Younger, c. 1535.

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Titchfield was the choicest of them all. The Premonstratensian abbey comprised a church, cloisters, chapter house, richly stocked library and living quarters. The immediate surroundings consisted of gardens, orchards, stables, a farm and a string of ancient fishponds in a natural hollow descending towards the River Meon. Beyond were the estates: nine thousand acres of land, fifteen manors, six dovecotes, six windmills and the rest. Wriothesley had had his acquisitive eye on it for some time and did his utmost to persuade the last abbot to hand it over voluntarily rather than under compulsion. He succeeded, and in December 1537 secured possession. He sold off what he did not want – the marble, sculptures, altars and fittings from the church – and set about converting the buildings into a residence befitting the man who, before long, would be the king’s Lord Chancellor.

Titchfield Abbey

Tom Fort

A castellated gatehouse with four octagonal turrets became the entrance to Wriothesley’s Place (a corruption of palace) House. Parts of the old church, including its tower, were demolished. The cloister became the central courtyard, the refectory grew into his great hall, and the rest of the abbey was converted into sumptuous apartments. There were four main fishponds, each feeding into the next one down; the three lower ones rectangular and the top one oblong. They were inspected by the new owner’s project manager and found to be good – ‘a mile in length … containing 100,000 carpes, tenches, breams and pike’.

The reference to carp is notable. The Letters and Papers of Henry VIII state: ‘The bailey will give Wriothesley 500 carp … Mr Huttuft providing the freight, Mr Mylls tubs, Mr Wells conveyance of the carps so that in 3 or 4 years time he may sell £20 to £30 of them every year …’

Carp were imports from the Low Countries. The first authenticated mention of them comes from the household accounts of the 1st Duke of Norfolk, which state that on 15 May 1462 ‘my master putt into the mylle pond … gret carpes’ as well as ‘gret tenches … gret and smale bremes’ along with roach and perch. The ponds seem to have been located near Layham in Suffolk, and there are several further references to ‘my master’ personally stocking his ponds. An entry for September 1465 refers to gifts of carp being made by the duke to ‘my lady Waldegrave’ and several others.

Originating from the lower Danube basin, probably in present-day Slovakia, carp had long been the domesticated freshwater fish of choice across continental Europe. Their virtues were manifold: they tolerated wide variations in temperature as well as low oxygen levels, grew fast and to a large size, were easy to breed and were catholic in their eating habits, and – compared with rivals such as bream and tench – made a tasty as well as substantial dinner.

It is strange that they should have taken so long to arrive in Britain. By the time the Duke of Norfolk was taking delivery of the first consignment for his ponds, there were 25,000 carp ponds and lakes in Bohemia, some of enormous size (and still producing big harvests of carp for the table today). It is the case that by then the heyday of pond construction in England had passed, but many of the existing ponds remained in use, and the manuals of the time show that the carp rapidly found favour with the discriminating pond owner.

It is not known if Thomas Wriothesley had a particular interest in the ponds at Titchfield Abbey. Given his other activities – diplomacy, intriguing against his former patron Cromwell, attempting to have Catherine Parr arrested, persecuting heretics and supervising the torture of the Protestant martyr, Anne Askew, and amassing a huge fortune – he may have lacked the time for more than the occasional stroll past their still waters. The later years of his shortish life – he died in 1550 aged forty-five – were largely devoted to his unavailing efforts to remain a power in the land in the immediate post-Henry period.

The mansion he had grafted onto the old abbey – ‘a right stately house embattelid’ in the words of the antiquary John Leland – survived him by a couple of centuries. Eventually much of it was dismantled by a subsequent owner, which had the effect of restoring to view a substantial portion of the original abbey, forming the romantic ruins still standing today.

The ponds, which preceded the arrival of Wriothesley and his minions by two hundred years, have fared even better. They must have been exceptionally well engineered, because they are still there – not as dips and lumps in the land or patches of reedy marsh, as with Prior More’s ponds, but substantial sheets of water of the kind to get any angler’s nose twitching. And the fish are there: tench, bream, roach and fine, fat common and mirror carp. Their welfare is attended to by the Portsmouth and District Angling Society (founded 1948) which obviously cherishes them and those who fish for them, judging from the sturdy platforms for anglers to sit in comfort, litter bins, notices and car park.

There was no one fishing the day I visited; it was October, when the best of the tench and carp fishing is over for the season. Autumn was in the air and the still, dark surfaces of the ponds were speckled with the first fallen leaves. I hoped to see the roll of a carp or a glimpse of the slab side of a bream, but it was very quiet. Extremely fishy, though, and marvellously secluded in a thick belt of trees that effectively muffled the snarl of the A27 half a mile away.

Carp became very popular as a luxury food item, and gave an extra incentive for some pond owners to look after their waters. Roger North in his Discourse of Fish and Fish-Ponds, published in 1713, wrote of the pleasure to be had from being able to ‘gratify your family and friends that visit you with a Dish as acceptable as any you can purchase with Money; or you may oblige your friends and neighbours by making Presents of them’.

North, a son of Lord North, moved in elevated social circles and may well have discussed this matter of mutual interest with Lord Wharton, whose great estate at Winchendon near Aylesbury included a number of ponds that he managed attentively. The records of the estate for 1686 reveal that the ponds were ‘drawn’ – presumably netted – between October and January: ‘I did draw Sir William Stanhope’s Pond and did leave and put into it since 254 Good big Carps … I did draw Spratlies Pond and I left in it and have into since 300 tench and 90 great Carps … the Horspond was drawn, I took 300 Great Carps out of it and put them in the pond next to it … in the Great Pond by the town there is 300 great Carp besides tench …’

The frontispiece of the 1713 edition of A Discourse of Fish and Fish-Ponds by Roger North.

A Discourse of Fish and Fish-Ponds by Roger North, printed for E. Curll in London, 1713. Sourced from Archive.org, Oxford University

Having earlier imagined Prior More walking through the cathedral precincts in Worcester planning the construction of his fishponds, I picture him now in his retirement in his manor house at Crowle surrounded by its moat.

It would hardly be apt to call his retirement well deserved, for he was a distinctly worldly prior even by the worldly standards of his time, conspicuous for rich living and prodigal spending of other people’s money rather than piety or attention to his devotions. He was fortunate to have reached retirement at all – many of his kind paid with their lives for their dedication to comfort. William was shrewd as well as lucky, and he spent many years at Crowle before dying in 1552 in Alveston, a village in Warwickshire where his brother Richard – a Bristol wine merchant who had profited well on orders from Worcester – had made his home.

I see William emerging from the front door of the manor house on another summer’s day in, say, 1546. Far away in London the king who visited such turbulence on the monks of Worcester is dying, gout-wrecked, ulcerated, obese. The vultures are gathering around him. But in Worcestershire peace reigns. The sun is lighting up the gables of the old house and the gardens and orchards beyond. The prior walks more slowly than when he was planning his great works. They are done now, and he approaches his favourite among them, the moat that encloses the house, with the tithe barn close by and the church reflected in the water.

He recalls the good times he has had here: William Smythe’s wedding, for which William gave five shillings so his servants could feast and carouse; the village bonfire on St Thomas’s Night, for which he supplied cakes, sack and ‘a quarte of red wynne’; a St James’s Day party at his neighbours the Winters, with minstrels, players and jugglers.

He reaches the bank of the moat and remembers that day in 1533 when he recorded in his journal that it was completed. He looks across its forty-foot width, and his eyes follow it as it curves around the garden’s edge. It is well made, he says to himself. The sun goes behind a cloud, comes out again, and the surface glows. He sees a broad back, a great golden flank, a round rubbery mouth opening and closing, the slow ripple of disturbance.

He thinks of his dinner. A dish of carp, roasted, with rosemary, marjoram, thyme and parsley folded into its belly.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.