Полная версия

Casting Shadows

Smyth eventually produced a family history in three weighty volumes. It is clear from this that fishing was not of great economic importance to what was, in effect, a mini-kingdom within a kingdom. But Smyth was a dutiful recorder, so he did not ignore the great expanse of water that formed the western boundary. For example, he listed the fifty-three known species of fish from the channel, which included such fictitious oddities as the horncake, the roucote and the thornpole, as well the more familiar salmon, eel, sturgeon and so forth. He also mentioned some of the families involved in the fishing. Among them were the Atwoods, several generations of whom had the fishery known as The Shard at Blackstone Rock between 1548 and the 1620s at annual rents varying from six shillings and eight pence to seven shillings and two pence.

The frontispiece to the 1883 edition of The Lives of the Berkeleys

The Berkeley manuscripts: The lives of the Berkeleys, lords of the honour, castle and manor of Berkeley, in the county of Gloucester, from 1066 to 1618 by John Smyth, published by J. Bellows in Gloucester, 1883. Sourced from Archive.org, University of Toronto

The fishing ‘places’ changed with the seasons, as the sands shifted with the tides, covering and uncovering the rocks and channels. Some were easier to get at than others. Grove’s Hole on the Oldbury estate – recorded in 1696 as having paid tithes ‘time out of mind’ – was a mile from the access point and was reached by horse and sledge.

Complex rules governed the obligations of tenants. One tide a week was known as ‘the lord’s tyde’ and all the fish taken on it went to the estate. Under the so-called Gale Tax, the lord could appropriate a salmon from the fisherman and pay him half the set price, or require him to pay the same sum to keep it. But if the fisherman managed to move it from the place of capture to somewhere above the high-tide mark and put grass in its mouth, the fish was regarded as exempt. To protect the local interest, all fish had to be offered at Berkeley Market Cross for one hour before they could be taken further afield to be sold.

The estuary is a world apart. It is made from river and sea but belongs to neither. To the eye, the land and sky merge with each other and the water, so that – as Philip Gross put it in a poem about the Severn – ‘the hills were clouds and the mist was a shore’. The toing and froing of the tides, covering and uncovering the land, create a realm suffused with dynamism and inconstancy, a wide shifting amalgam of river, sea, land, sky, space and light, shaped by what someone once called ‘the never-ending pas de trois of earth, water and moon’.

Inevitably those who lived on and from the estuary formed a race apart, geographically and culturally. The rhythms of their daily lives were very different from and more complicated than those of the peasants who worked the land, who rose with the sun and lay down when they could no longer see what they were doing. For the estuary fishermen, the tides – ebb and flow, neap and spring, all the variations between – dictated how they expended their energies. Their inner tide tables would have been spliced into awareness of the seasons: when the spring salmon were running, when the eels would migrate in the first storms of autumn, the arrival and departure of the migrating waders, ducks and geese, the nesting times when eggs would be ready for taking.

They inherited knowledge and added to it. Making and maintaining a fish trap required a major communal effort. It had to be in the right place, and the inconstancy of the estuary meant this changed. A trap would have a limited life span; sometimes it was rebuilt in the same spot, but often the location was shifted, reflecting the impact of erosion on the shorelines and the movement of channels and mudbanks. As the Irish archaeologist Aidan O’Sullivan put it in an illuminating paper, ‘Place, Memory and Identity among Estuarine Fishing Communities’, they were archaeologists themselves and ‘would actively have built their knowledge by their observation of ancient wooden structures on the mudflats’.

These communities would have had contacts with the outside world to trade their catches and pay their dues. But the inherent bias resulting from reliance on written sources – suggesting that the anonymous working classes were closely controlled in their daily lives by the ruling class and regarded their first duty as being to serve the interests of the ruling class – is particularly wide of the mark in this context. These fishing families were geographically and culturally isolated and must have felt themselves so. They had their own language – there are countless Severn words for different aspects of the fishing heritage. They were born, they married, they procreated, they died within the sound and smell of their salty, shared place. They pursued their own interests with not much more than a nod towards wider obligations. Their knowledge and experience were matters of life and death to them, but of no use elsewhere.

With their passing, all that dies with them.

CHAPTER TWO

Night Harvest

Just west of Glastonbury and its myth-laden Tor, the River Brue diverts abruptly from its northern direction and turns north-west in a straight line beside the road to Meare. It is termed a river but it owes very little to the processes that first shaped this soggy landscape.

There are several obvious clues to its artificial provenance. Much of its course is in straight lines or flattened regular curves with none of the normal riverine meanders. It is raised above the surrounding countryside, so that it actually flows above the level of the Meare road. Its embanked sides shut it in, blocking any view from a distance. It has its tributaries, but these – like the mother flow – are drawn in straight lines, their contributions controlled by multiple sluices.

Meare is three miles or so from Glastonbury. The Brue is directed around the north of the village, close but keeping its distance. On the eastern side of Meare there is an irregular tongue of lush green meadow between the river and the road. The land slopes a little up from the river, enough to keep the curious old building that stands on its own in the meadow safe from the floods that have always troubled this region.

I cycled out from Glastonbury on a clear, mellow October evening to see Meare’s celebrated Fish House. You cannot miss it: a very plain, upright oblong with pale, worn grey stone walls and a tiled roof, and a very beautiful decorated window in each of its gables. Across the meadow is its companion, the manor house. They were both built in the early fourteenth century, quite possibly by the same hands. With its orchards, vineyard, dovecote and windmill – and the chapel a stone’s throw away – Meare’s manor house formed an integrated complex.

Meare Fish House

Tom Fort

It was laid out for the pleasure of a notable prelate at a time when abbots and bishops were as powerful a force in the land as the lay lords. The manor house, the chapel – subsequently church – and a portion of wall survive, but the orchards, gardens, vineyard, dovecote and windmill do not. Even so, it is quite easy to picture it as it was: a place of ease, even luxury, where the retired Abbot of Glastonbury, Adam of Sodbury, could pray and stroll and receive his guests in his great hall and reminisce about the challenges he faced in keeping Glastonbury pre-eminent among the great religious houses and its assets and estates intact.

But the Fish House does not tell such a straightforward tale. Standing beside it as the light faded, I tried to work out its context, what it was doing there, what its purpose had been and who used it and how, and what the view from it would have comprised. I had read about it at length but relating the words of archaeologists and historians to what was in front of me required an effort of the imagination, as there are few landscapes in Britain that have been more thoroughly transformed over the ages than the Somerset Levels.

Fifteen hundred years before Abbot Sodbury was planning his rural retreat, the region to the north and north-west of Glastonbury Tor would have seemed a forbidding place. The Brue – the ‘old’ Brue, bearing no resemblance to the regimented watercourse of today – wandered north and found its way through a gap into the Axe valley, where what there was of it joined the Axe itself. It crawled through a swamp, thicketed with scrub, with the occasional patch of slightly raised and drier land covered in alder and birch. There were innumerable ponds and meres, shallow and reedy. Towards Meare the swamp was bounded by a raised peat bog covered by moss, cotton-grass and heather, pitted with hummocks and, again, dotted with pools of water. On the edge of the bog were two substantial humps, drier (but by no means dry) and therefore offering the possibility of human occupation. Around 300 BCE the two humps became the sites of seasonal camps for Iron Age migrants. A little after that – fifty years or so – a similar but drier and more stable bedrock island just north of Glastonbury was occupied and became a permanent settlement of roundhouses with clay walls and floors, hearths and thatched roofs.

Collectively, but misleadingly, all three were dubbed the Somerset Lake Villages when their existence was revealed towards the end of the nineteenth century. The Glastonbury site was certainly a village, occupying almost 1.5 hectares (3.5 acres) and housing as many as two hundred people. Meare was much less stable and congenial, and although brushwood, timber and clay were spread across the bog surface to make temporary floors, no sign of permanent occupation ever came to light.

The excavation of the lake villages was a heroic enterprise instigated, organised and overseen by a Glastonbury-born doctor, Arthur Bulleid, which lasted more than half a century until halted by the imminent outbreak of war in 1938. Vast hoards of Iron Age remains were recovered, which gave a remarkably full picture of how the villagers lived. It is clear that by the standards of the time they were well equipped, well fed, possibly even well content. They had axes, billhooks, sickles, slings, cookpots, wooden ladles, mallets, ladders, metal-toothed saws and doors with iron latches. They wove cloth and worked metal, bone and antlers into useful tools and ornaments. They knew how to rivet sheets of bronze and how to hollow a boat from a trunk of oak. They had iron spears, and some had swords; they had horses for travel and vehicles with spoked wheels. They had necklaces made of amber and glass beads, used tweezers and polished bronze mirrors for personal care, got their whetstones from the shore of the Severn, played games with counters and dice.

They reared sheep, pigs and a few cattle. They hunted red and roe deer, otters, beavers and foxes. They shot or netted a wide range of birdlife including ducks, geese, herons, cormorants and gulls. They foraged nuts, berries, herbs and plants and grew emmer wheat, spelt, barley, rye, oats, peas and beans.

And, of course, they fished. Among the objects found in the camp sites were considerable numbers of sinkers used to hold nets in place. The nets would have been set from their slender shallow-draught boats which were the only practical way of getting around. The villagers would have eaten the occasional salmon traded with fishermen from the Bristol Channel. But their focus closer to home would have been the local species – roach, perch, pike and, much the most important, the abundant, ever-present, tasty, protein-packed freshwater eel.

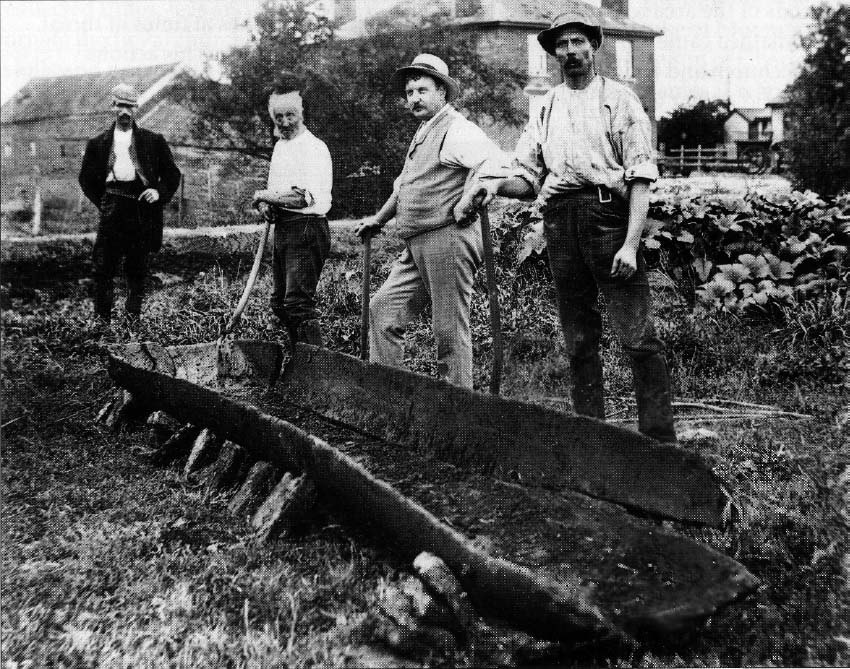

The Shapwick canoe, discovered in 1906 in an early excavation of the Somerset Lake Villages, is an iron-age dugout canoe.

Image courtesy the Watchet Boat Museum, with thanks to John Eastaugh

The lake villages lasted a couple of centuries or so before being abandoned – almost certainly because of rising water levels. Storms raged, the rivers overflowed, the swamp became a patchwork of lakes, and the hummocks and bedrock outposts were invaded. In time the floodwaters closed over where the lake villages had been, covering the sites in silts and clay.

Thereafter this part of the Levels reverted to being an uninhabited watery wilderness. But sometime in the centuries after the end of the Roman occupation, someone – there is no more precision than that – began to tame it for the purposes of human occupation and exploitation. It is likely that the monks of Glastonbury Abbey – founded early in the seventh century CE – directed the process. Certainly by the time the veil obscuring the Anglo-Saxon period was lifted in the histories of William of Malmesbury (twelfth century) and John of Glastonbury (mid-fourteenth), the landscape had changed drastically. By then the draining of the more accessible and amenable parts of the Levels was well advanced.

Most strikingly, the northerly wandering of the Brue towards the Axe valley had been cut off, and a new course engineered to the west that took it to the Bristol Channel at Highbridge. Several other streams had been canalised and new ditches and watercourses constructed to create a network of drainage channels.

One of the consequences of this aquatic rearrangement was the creation of a considerable lake just north of Meare. This was known in the Anglo-Saxon period as the Ferlingmere, later as Meare Pool. This haven for fish and wildfowl was the reason Abbot Sodbury had seen fit to commission his Fish House.

The pool was a medium-value asset for Glastonbury Abbey. The Domesday survey lists it as supporting three fisheries paying twenty pence a year each, with ten fishermen. Fish traps along the neighbouring stretch of the new Brue were valued at 100 shillings. By the early twelfth century the manor of Meare, including the pool, was within the Glaston Twelve Hides, an area granted to the abbey in a succession of charters between 670 and 975 CE and subsequently confirmed by Henry I and Henry III.

The legal and fiscal privileges enjoyed by the Hides aroused the envious avarice of successive Bishops of Bath and Wells, Savaric (1191–1205) and Jocelin (1206–41), who intrigued over many years to annex the abbey and its lands. In 1218 a commission awarded a quarter of the abbey’s estates, including Meare and eight other manors, to the bishopric. The ruling was subsequently reversed, but there was continuing bad blood between the two Christian power blocs which periodically spilled over into open conflict. There were allegations of trespass, and the mutual rights of turbary – to cut peat for fuel on each other’s land – caused endless trouble. The abbot’s men destroyed a piggery belonging to the Dean of Bath and Wells. The dean’s men breached dykes and pulled down a fish trap belonging to Glastonbury. A fire was started on a Glastonbury peat moor, and horses, oxen, cows, bullocks and pigs worth £200 were stolen at Meare. Eventually the feud petered out, and in 1320 a comprehensive agreement on the division of lands and the protection of reciprocal grazing and other rights was reached.

In the more tranquil atmosphere, Meare became the favoured out-of-town refuge for the abbots of Glastonbury. Although the ‘new’ Brue acted as an important drainage outlet to the west, its prime function as far as Glastonbury was concerned was as a means of transport to and from Meare. One of the abbey’s head boatmen, Robert Malherbe, was charged with bringing the wine from various vineyards, maintaining the waterways, and steering the boat that conveyed the abbot plus cooks, kitchen equipment, huntsmen and hounds to whichever of his residences took his fancy. A steady supply of pike, perch and eels was conveyed along the Brue to the abbey’s kitchens.

The Fish House was built to organise and guarantee this supply. There were two floors, the upper of which – two rooms in which the fishermen are assumed to have slept and eaten – was accessed by an external staircase, later destroyed by fire. The three ground-floor rooms were probably used for making, repairing and storing nets and other gear, and perhaps for gutting and cleaning the fish destined for either the manor house or the abbey. Outside, between the building and the pool, were three modest-sized fishponds used for keeping fish alive and, possibly, breeding them.

The extent of the pool would have fluctuated according to the season and the rainfall. Three surveys from the first half of the sixteenth century refer to it as being about a mile long by three-quarters of a mile wide. One of them, carried out in preparation for the imminent dissolution of Glastonbury Abbey, records ‘a great abundance of pikes, tenches, roaches and eeles and diverse other kinds of fish’.

In September 1539, on the orders of Thomas Cromwell, the last Abbot of Glastonbury, Richard Whiting, was arrested, subjected to a show trial at Wells, dragged on a hurdle to Glastonbury, hanged on Glastonbury Tor and drawn and quartered, his head being set upon the Abbey gate and the rest of him displayed at Wells, Bath, Ilchester and Bridgewater. It was a typical Cromwell display of ruthlessness and cruelty. ‘Let the evidence be well sorted and the indictment well sorted’, he wrote on the eve of poor Whiting’s trial.

Within a few weeks, the most ancient and perhaps the most beautiful abbey in England had been stripped of its treasures by Cromwell’s henchmen and left to rot, its stones dragged away to improve the road to Wells. Meare Pool was not among those treasures but its days were numbered. Attention was beginning to be given to the profits and increased food production made possible by reclaiming wetlands for growing crops. By 1630 a Mr William Freake ‘had drayned manie acres of ground’ near the pool, and a few years later it was described as ‘lately a fish pool … drayned so that there is neither fish nor swannes in the same’. By then part of the complex network of canalised rivers and artificial watercourses we see today was in place. But the area remained an intractable one from the point of view of agricultural improvement, and it is likely that part of Meare Pool remained open water into the eighteenth century.

The halting progress of land-improvement schemes in the Somerset Levels was organised and funded by well-to-do landowners eager to augment their income and power. As always, the common people were not consulted, were indifferent to the concept of progress, did the hard labouring required, and put up with the consequences. They would never have shared the assessment of the pre-drainage Levels as a barren wasteland. Like those lake villagers of old, they would have acknowledged what the historian of the Levels, Michael Williams, termed the ‘hierarchy of usefulness’. There were pools and sluggish streams abounding with fish and fowl and tasty eggs; beds of reeds and withies to be cut and used to repair roofs and make baskets and traps; deer and otter to be hunted, berries, nuts and plants to be foraged; and there were the drier patches where a few animals could be grazed and crops grown.

The techniques and strategies that enabled the people of the Levels to exploit the natural resources around them did not die because the Levels were drained, tamed and turned over to agriculture. They were always part-time activities, done on the side when other duties permitted, not economically vital but valued extras that contributed immeasurably to the texture of hard lives. A dish of rabbit or venison or grilled eel, a plate of duck eggs, a slug of home-made sloe gin – these were precious treats in an existence characterised by hard slog. Although the overall economy of the Levels was transformed by drainage projects, there was no compelling reason for the people to give up their hunting, foraging ways. They were woven into the tapestry of their world, cherished for helping define who the Levels people were and their heritage.

Meare Pool had gone but the rivers, rhynes, ditches and ponds were still full of fish. And of those fish none was more prized, more persistently pursued, or more deeply etched into the shared consciousness than the freshwater eel.

Almost twenty years ago I wrote a book about the eel and its improbable life cycle. I read everything that had been written about it. I travelled around England, to France, Northern Ireland, Italy, Denmark and the USA to meet and talk to men who fished for eels, or who had become obsessed with studying them. I fished for them myself, not very successfully, and I dreamed about them persistently.

The original cover of The Book of Eels, 2002.

Image courtesy HarperCollinsPublishers. Photographed by Jason Hawkes

Researching and writing that book filled me with an immense sense of wonder at one of the truly astounding life stories of our planet, which I have never lost. The wonder springs from the physiological complexity of the creature; but perhaps more from the contrast between the epic, almost inconceivable migrations with which the life of the eel begins and ends, and the extended period of invisible, sedentary residence in between. I spent many happy library hours poring over the accounts published by the great Danish biologist, Johannes Schmidt, in which he described tracking the route of the eel larvae from the Sargasso Sea to the shores of Europe. Through Schmidt’s dry, academic prose I glimpsed the spectacle of the birth in the deep, clear, warm, salty waters of the clouds of minute specks of eel life, and their slow drift on the Atlantic currents.

I stood in the darkness beside an ancient Severn elver fisherman as he dipped his net to intercept a portion of the silver stream of little fish borne inland on the tide. I went out with the last proper Thames eel fisherman and watched him lift his fyke nets from the grey estuary waters out from Erith. I sat with a retired US state trooper on his eel rack on the Delaware River in New York State discussing his dysfunctional family while waiting for the migrating silver eels to run downstream.

As I listened to him, I imagined that same instinct at work along the distant coasts of Europe: eels awakened from years, even decades, of placid, monotonous existence by the silvering of their bellies, the swelling of their sex organs, the widening of their eyes; slipping downriver one black, rain-lashed night to the salt water, and then out to and across the ocean. No one has ever followed that journey, but I could see it in my mind’s eye: the meeting and mating and dying beneath the clods of sargassum weed that hang on the surface, the final drift down to the floor of the sea fifteen thousand feet down to be fed on by the outlandish lanternfish and hagfish.

I did my best to communicate that sense of wonder in The Book of Eels, as well as recording everything that was known then about the eel, and summarising the mass of informed speculation about what was not known – the unknown exceeding the known by a very long way. Since then the knowledge has increased very little, although the flow of guesswork has continued unabated. We still do not know what triggers the migratory transformation or how they manage to navigate their way to the Sargasso Sea three thousand miles away, never mind what actually happens when they get there. We do not understand their gender division. We do not understand why some eels stay in salt water and eschew fresh water, while others do the opposite. The population dynamics remain a mystery: we have no idea how abundant eels are, or even where they are.