Полная версия

Casting Shadows

Elver fishermen with their nets on the banks of the River Severn, near Gloucester. Photographed by John Tarlton.

The Museum of English Rural Life, University of Reading. Photographed by John Tarlton

What has become much clearer since I wrote the book is that their numbers have declined very steeply in the freshwater systems where, until a generation ago, they were abundant. This vanishing from places where they were once common – to take one example, the chalkstreams of southern England – has understandably been interpreted by scientists as proof of a wholesale crash in eel stocks, threatening the very survival of the species. The consensus quoted by experts across Europe is that the population has declined ‘by 90 per cent’. They may be right, but they do not know: the figure is an extrapolation. And it is an awkward fact that in some locations – the Thames Estuary, for instance, or Poole Harbour – there are still healthy populations of eel, as far as we know.

That is the nub. The reason we know anything about eel abundance in the past is that people went out to catch them – not because scientists studied them. Eels are easy to catch if there are plenty around and you have spent a lifetime catching them, but hard if you haven’t. Scientists generally haven’t and are bad at catching them. They used to rely heavily on eel fishermen for data. But for reasons I shall look at more closely later in this book, there are very few eel fishermen left. The data has become ever more sketchy, the temptation to engage in hypothesis more potent.

The Somerset Levels, like the Fens, constituted a perfect domain for the eel. The elvers were sucked into the great maw of the Bristol Channel in their fluttering silver hordes each spring. The majority were drawn onward into the Severn Estuary, but a good proportion were claimed by the north Somerset rivers, principally the Parrett, the Brue and the Tone. If they evaded the battery of predators – including the elver fishermen dipping their big nets in the darkness of night – they filtered inland, replenishing the populations along the rivers and spreading like blood through veins up the tributaries and the streams feeding the tributaries and the network of man-made channels that drained the moors, reaching the pools and ponds. Everywhere they found ideal eel habitat: somewhere to hide, to feed, warm water in summer, soft mud against their bellies to sink into when winter came.

Salmon and eels – throughout our history these have been the two chief food sources among our freshwater species. Although there has been a degree of crossover in the methods of catching them – the putchers on the Severn, for instance, took both – overall they required different approaches and engendered different attitudes. Building, maintaining and monitoring traps for salmon demanded co-operative effort, as did netting; and that effort was focused on particular times of the day as well as seasons, reflecting the limited nature of the opportunities. But the eel is there all the time, and in the half of the year that it is active – say May to October – it can be caught anywhere and at any time.

Eel fishermen do not need to be part of a team. They work alone or with a single partner. They are deeply suspicious of other eel fishermen, fearful that their special places and tricks will be spied on. By nature they are extremely stingy with information, and anything they tell you about their trade should be viewed with the same suspicion that they display to all and sundry. Eel fishermen are not as other men. They are solitary, they are accustomed to lonely, watery places and the night. They like eels.

On the Somerset Levels eels were extremely common and easy to catch. The methods were age-old and simple. You could walk along the edge of a rhyne with an eel spear – a long-handled fork with pronged tines – plunging it into the mud, and be sure to come up with an eel thrashing between the prongs before long. If you laid a sack of straw on the bottom with a length of clay piping stuck in it, the eels would creep in for cover during the night and could be tipped out into a bucket in the morning. Baited traps of woven green willow were put out for them. Another technique was known as rayballing or clotting: worms were threaded into a loose ball of wool and lowered at the end of a pole into a likely spot, where the eels would attack it and snag their teeth on the wool so they could be lifted and dropped into a bucket or sack. Nets were widely used, and in the first storms of autumn the migrating eels – silver, packed with fat for the journey, the best eating – were taken in the traps installed on weirs.

The one significant innovation denied to the old-timers was the arrival from continental Europe in the 1970s of the fyke net. This was neatly described by the celebrated elverer, eel catcher and smoker Michael Brown in his eel memoir Moonlighting, as looking like ‘a windsock attached to a tennis net’. It is a peculiarity of eels that when they encounter a net on their nocturnal wanderings they follow it. Whoever invented the fyke net – I can find no record of its origins – exploited this tendency by putting together a wall of netting with holding traps at intervals into which the eels stray, and where they seem content to remain until removed and consigned to the food chain.

Leaving the fyke net aside, the continuity stretching back to time immemorial would have enabled the lake village dweller of Glastonbury or Meare two centuries before the life of Christ to know exactly what the eel fisherman on the Brue was up to two thousand years later, and the other way round. Everything else had changed, but not this helping yourself to what nature had provided on your doorstep. Michael Brown’s chief helper, Ernie Woods, grew up in the 1930s close to the River Parrett, living on and off the moor. ‘I’ve et everything that moved down on that there moor,’ he told Brown. ‘Fish, eels, elvers, swan, duck, rabbit, crow – you name en, I’ve had en.’ As a boy Ernie speared eels, skinned them, and sold them around the village. When the elvers ran in the early spring, the family simply dug a trench from the river into their garden to divert a portion their way.

The writer Adam Nicolson went hunting eel fishermen for his book Wetland: Life on the Somerset Levels, on which he collaborated with the photographer Patrick Sutherland. One, Arthur Stuckey, described drifting along on the front of the boat poking a fifteen-foot eel spear into the mud. ‘You’d catch four or five at a time, they couldn’t get out past the notches,’ he reminisced. ‘But it was banned after the war.’ Arthur’s father kept an eel trunk in the river, six feet long and with a perforated cover, in which the fish were kept alive until there were enough to be worth sending up to London ‘where the Jews wanted them’, as Arthur put it delicately.

Although fishing for eels was in the warp and woof of Somerset Levels life, and the supply of eels and the maintenance of eel traps were matters of interest to Glastonbury Abbey and the other religious houses, it was never as significant economically as in that other great expanse of English marshland, the Fens. The tenth-century foundation charters of the Fenland Benedictine monasteries and abbeys illustrate how seriously the monks took their eels. Villages near Wisbech were recorded as catching 16,000 eels a year – half allocated by Bishop Aethelwold to Thorney Abbey, half to Peterborough. Ely’s charter of 970 CE included 10,000 eels a year from Outwell and Upwell.

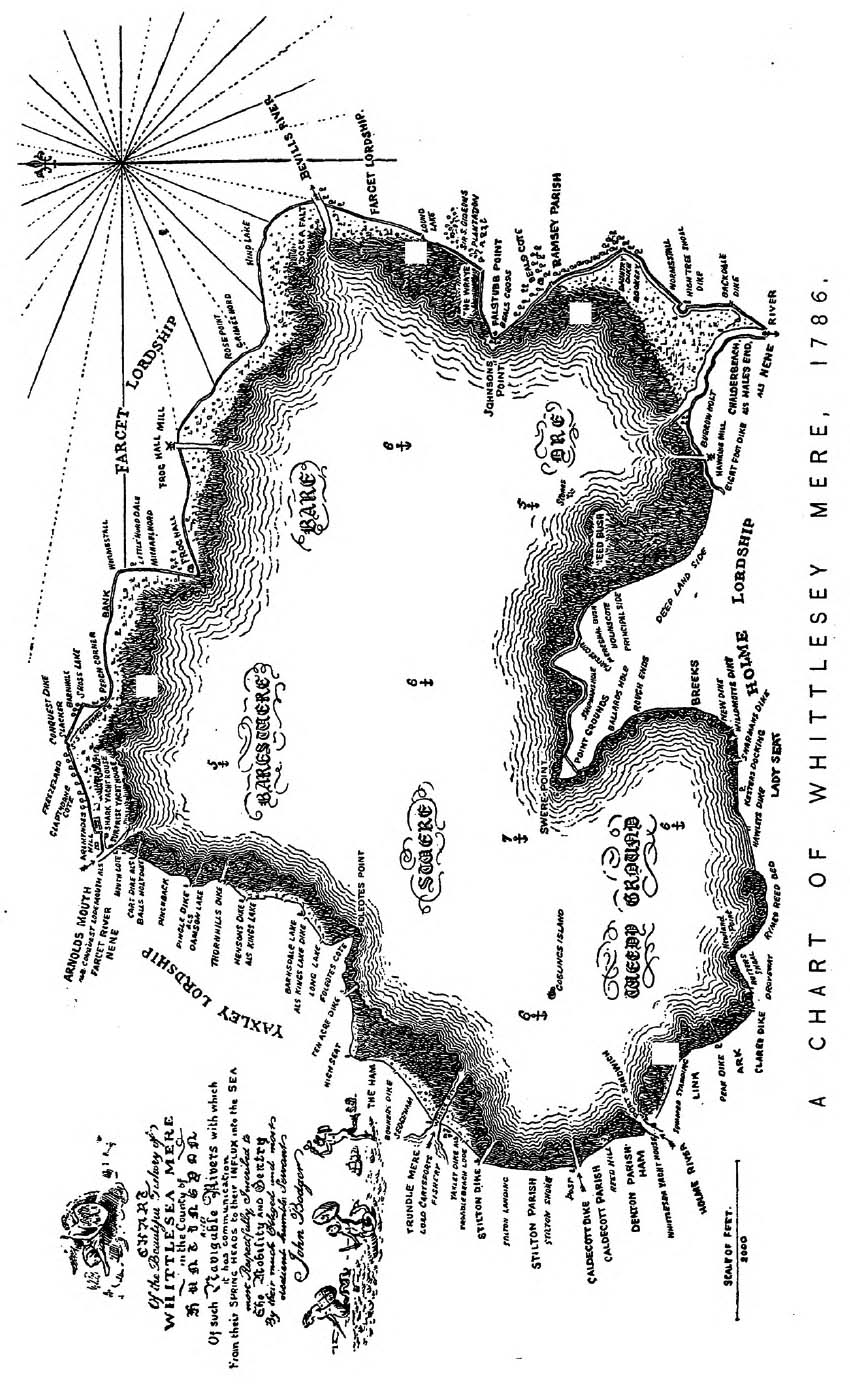

The Domesday survey provided a detailed breakdown of fisheries. The abbots of Ramsey and Peterborough were recorded as having a boat each on the great expanse of water known as Whittlesey Mere, north of Holme Fen in what is now Cambridgeshire, while Thorney had two. Ramsey also received rents measured in tens of thousands of eels from fishermen at Wells, on the Norfolk/Cambridgeshire border, and in the later Middle Ages snapped up eel fisheries all over the place.

The sheer abundance of fish in Fenland was evidently a standing joke. The chronicler William of Malmesbury wrote in the twelfth century: ‘There is such a quantity of fish as to cause astonishment in strangers, while the natives laugh at their surprise.’ The Liber Eliensis of about the same time recorded the capture of ‘innumerable eels, large water-wolves [lupi aquatici in Latin, presumably pike] … roach, burbots [now extinct in Britain but still found in Scandinavia] and lampreys … together with the royal fish, the sturgeon.’

Whittlesey Mere, 1786.

Fenland Notes and Queries, vol. I edited by W.H. Bernard Saunders, published by Geo. C. Caster, Market Place in Peterborough, 1891. Sourced from Archive.org

It was common practice to calculate rents in ‘sticks’ of eels, a stick comprising twenty-five fish. The busiest time for transactions was Lent, for obvious reasons, even though at that time of year the eels would, most likely, have been salted ones from the previous season. When Ramsey agreed to pay four thousand eels per annum to Peterborough in return for a supply of Barnack stone to build its abbey, it was stipulated that the fish should be delivered in time for Lent.

The eel economy of the Fens was unusually valuable and therefore well documented. But wherever eels were found in England – they bothered with them much less in Scotland and Wales, where they had salmon – they were trapped, netted and speared, and eaten and traded. Monasteries and secular lords maintained traps all the way up and down the Severn and Thames, for example, which were used to take salmon when there were salmon, and silver eels in the autumn migration.

But the written records are dry and transactional. They show the fishing was happening, who owned it, how much it was worth, but reveal nothing about who was doing it and how. Records of court proceedings provide an occasional snippet: how at Littleport, north-east of Ely, one ‘John Beystens drew the pool at Wellenheath by night and carried thence fish price 6d and that he ought to be removed out of the vill’; how ‘Walter of the Moor against the peace of the lord came on such a night at the hour of midnight and entered the preserve of the lord … and carried off at his will every kind of freshwater fish … and carried the fish with him and made boasts of this …’

On the whole it was not until much later, when educated men and women discovered the excitement of travel and became curious about what was going on in distant places, that more information emerged. Many generations of Fenland families had fished Whittlesey Mere and helped themselves to its reeds, sedge and wildfowl before that tireless seventeenth-century traveller Celia Fiennes passed by and observed it to be ‘3 mile broad and six long … in the midst is a little island where there is a great story of wildfowl … the ground is all wet and marshy … ye Mer is often very dangerous by reason of sudden winds but at other times people boat it round with pleasure … there is abundance of good fish in it …’

Whittlesey survived the organised draining of the Fens and continued to function as a valuable natural resource well into the nineteenth century. Trading boats were able to ply between the mere and the town of Whittlesey and a considerable business was done in cutting reeds for thatching and sending them all over the country. A reed merchant from Yaxley, Joseph Coles, paid £700 a year for the fowling, fishing and reeding rights. Gradually, though, the mere was silting up and in 1848 the local bigwigs co-operated in having it drained and converted into agricultural land. Great crowds gathered to watch Whittlesey Mere’s death throes, and to help themselves to the multitudes of stranded fish – which included a vast eel ‘with a head as big as a dog’s and teeth that bit through the heel of a gutter boot’.

The mere was no more and the Whittlesey fishermen – their voice entirely unheard – presumably went off to try elsewhere. There were plenty of alternative venues – the draining of the Fens over the centuries had created a huge network of artificial channels, all of them high-grade residential areas for eels. The fishing went on, and just occasionally an eel-fisher made himself heard.

One such was Ernie James of Welney, one of the last of the true Fen Tigers, the term for those who lived in the remote pockets of fenland that had survived the drive for reclamation, and deployed diverse means to make their livings. Ernie James was born in 1906 and brought up in his parents’ cottage which stood between the Delph and the Old Bedford rivers. He was chiefly celebrated as a punt gunner, and one of his clients in that capacity was James Wentworth Day, an assiduous chronicler of Fenland life (also an extreme right-wing High Tory bigot whose brief career as an early TV pundit was terminated after he offered his opinion that all homosexuals should be hanged).

In his A History of the Fens Wentworth Day reproduced a lengthy letter from Ernie James which gives a strong flavour of the Fen Tiger life. James’s father had a line in selling eel grigs – traps made from withies from his own osier beds beside the Delph – and Ernie James recalled getting forty stone in a night during a summer flood, he and his father emptying the grigs at midnight and again at 4am. He described glaiving, their word for spearing: ‘I used to do some glaiving … but since the Delph was dredged the eels don’t stop like they used to … I have often glaived a stone out in three hours then skinned them and sold them in the village. Hard work, I can tell you.’

Wentworth Day also included an affectionate, even loving portrait of William Kent, from a family of ‘punt-gunners, eel-catchers, reed cutters, pike fishermen and makers of things with their hands’, crafting a six-foot eel grig using his own withies. ‘When I was a boy’, Wentworth Day sighed, ‘every dyke and lode had its grigs, which one could see lying shadowy amid the forests of water weeds on the bottom. Nowadays you could walk through the Fens for a month and never see a grig set.’

That was 1954. Ernie James lived to be ninety-nine and was still trapping eels into his nineties. But they have all gone now, the last of the Fen Tigers, and the eel fishermen of the Somerset Levels. I do not mean that no one takes eels any more, because a handful do. But that way of life – a weaving together of different but complementary and sustainable ways of exploiting the natural world around – has gone and will never return.

I spent a while strolling around Meare’s Fish House, trying in my mind to make sense of the past, to relate the tranquil flat meadows stretching away from the River Brue – the grazing cattle, the pylons, the functional farm buildings – to the fishy, watery history. I carted my bike over a gate and across a footbridge over the Brue, then pedalled strenuously along some of the embankments, occasionally having to dismount and push when the grass was too thick.

The map showed the various channels dug to keep the landscape in order and restrain Meare Pool from coming back to life: Pitts Rhyne, Waste Rhyne, Decoy Rhyne, Galton’s Canal, White’s River, James Wear River. They are quite mysterious, these ruler-straight, sunken pathways of water – dark, steep-sided, reedy, weedy, still.

The Brue, however – as befits the senior watercourse – boasted a perceptible current. A little way below the confluence with White’s River and above the bridge taking the old road known as the Blakeway over the Brue, I saw fish moving – not tiddlers, but decent fish. At first I thought they must be chub, but they did not behave in the leisurely way chub do. They seemed more urgent, as if searching for something. I wondered if they might possibly be an adventurous shoal of grey mullet – it is no more than ten miles to the sea, and mullet do wander.

I saw no eels. But they were there, somewhere.

CHAPTER THREE

A Passion for Ponds

I like to picture Prior More of Worcester on a fine summer’s morning in, say, 1521. He has said mass in the cathedral and had a series of conversations on administrative matters with certain monks under his direction. Now he is free to consider other things on his mind.

He walks slowly from the cathedral along the cloisters and out onto the green leading to the broad River Severn, deep in thought. He is of medium height, slightly plump, conspicuously well-fed, his cheeks coloured like the blush on a Worcester apple. He considers how well he has done for himself: born forty-eight years ago to parents of modest means in a modest village a few miles upstream, ‘shaven into ye religion ye 16th day of June, St Botolph’s Day AD 1488’, his uphill path starting in the priory kitchen as a lowly servant.

William is now, by some distance, the most powerful man in Worcester, powerful enough to be designated My Lord Prior. The city has a bishop, of course: Silvestro de’ Gigli, an Italian who has never left the shores of Italy and would not know where to find Worcester on a map (his equally absent successor, Giulio di Medici, would become Pope Clement VII in a few years). But by ancient privilege granted from Rome, the prior is entitled to wear a mitre and ring, carry a pastoral staff, and give solemn benediction at mass and table. He is bishop in all but name.

He has wealth and power. His standing is that of a regional magnate. He entertains the gentry and the civic leaders. When a great personage such as the child Princess Mary Tudor comes to visit Worcester, she and her entourage stay with him and he is in charge of all arrangements and festivities. Most years he spends several weeks in London, where he entertains powerful prelates and courtiers. Otherwise he passes weeks at a time at one or other of the priory’s manors, in which he takes a keen interest. In fact he is not often in Worcester itself, although he is careful to be present for Christmas, Easter, Quinquagesima, the Rogations and the other important Christian festivals.

This morning William’s tonsured head is full of calculations and assessments relating to his native village, Grimley, and his plans for it. How much clay will be needed to build up the first dam? How will the spring be kept clear? Where should the sluice be best placed? How much should he pay for the stakes to reinforce the banks? When should the stocking be made and how many? How many eels should he require to be delivered at the wharf?

Prior More takes out a small book and makes some notes. Later he will itemise the work he is to commission and the cost in his journal. He is a man with a considerable passion for fishponds and in the England of 1521, with his position and power, he has ample means and opportunity to indulge it.

The frontispiece of the 1914 edition of the Journal of Prior William More.

Journal of Prior William More edited by Ethel Sophia Fegan, published by M. Hughes and Clarke in London, 1914. Sourced from Archive.org, University of California Libraries

It is recorded that in 1257 Henry III and his court celebrated St Edward’s Day, 13 October, with a feast for which 300 pike, 250 bream and no fewer than 15,000 eels (I have my doubts about that figure) were supplied. Where the organisers secured such a vast multitude of eels is unknown, but it is a fair bet that some of them, and some of the other fish, would have come from one or other of the networks of artificial fishponds maintained at the Crown’s expense in various parts of the country.

Fishponds were symbols and expressions of status and wealth – like bowling-greens in the seventeenth century, landscaped parks in the eighteenth, follies in the nineteenth, or giant yachts and football clubs in our own time. The science of constructing ponds to breed and store freshwater fish can be assumed to have arrived here from France in the wake of William I and his knights. There was a royal pond or system of ponds on the north-east side of Stafford as early as the middle of the twelfth century; the records show it was let to William, son of Wymer, for half a mark. A later Wymer, Ralph, was allocated three oaks to repair it, and around 1250 the order came from London for one hundred bream, one hundred tench and thirty pike to be taken, salted and transported to Westminster without delay.

The pond at Stafford must have been highly productive. In 1281 the king’s fisherman, the queen’s saucemaker and ‘a boy’ were sent there for two weeks with instructions to send the catch to Edward I in Wales. The saucemaker was paid three shillings for his work, the king’s fisherman and the boy shared four shillings and a penny.

The records of the palace at Woodstock in Oxfordshire are peppered with references to repairs to the fishponds fed by the River Glyme, and to stocking them. The bailiff was instructed to secure one thousand pike ‘wherever he might find them’ to stock the king’s stew. William, the king’s fisherman, was sent to get six pike and deliver them salted to his employer. The royal ponds at Marlborough were a notable source of bream for breeding, which were supplied – presumably at a price – to fish fanciers in Lincolnshire, Wiltshire, Gloucestershire and elsewhere.

Where the king led, lords and bishops and abbots tended to follow, in the matter of fishponds as in other tastes. The proliferation of fast days prescribed in accordance with the teaching of St Benedict was a distinct stimulus to the eating of fish and the trade in supplying them. But, as the social historian of the Middle Ages, Professor Christopher Dyer, has elegantly demonstrated, the consumption of saltwater fish – generally salted cod or herrings – greatly exceeded that of freshwater fish. That applied even when the consumer was far from the sea. For example, the accounts of Bishop John Hales of Coventry and Lichfield show that in 1461 he and his household ate two-and-a-half times as many sea fish as freshwater fish (overall consumption of fish was a little under half that of meat).

Fishponds were laborious and expensive to construct and laborious and expensive to maintain and clean. It took several years for fish stocked in infancy to reach a size fit for the feast, plus a considerable investment in planning. In many parts of the country the secular and ecclesiastical powers were in the happy position of owning fishing rights on rivers where the most prized species for eating – salmon and eels – could be trapped at comparatively low cost. It was often more convenient and cheaper simply to buy in fish caught elsewhere as and when they were available.

The rich and powerful liked the idea of fishponds for a while, but when the bills came in and kept coming their interest tended to wane. It took a true enthusiast to persist with them. One such was Prior William More.

I had a long, draining day on the trail of More’s enthusiasms. I took the train to Worcester with my bicycle and – having visited the city’s spanking new library, The Hive, to learn more about my subject – set off up the left bank of the Severn full of vim and investigative vigour.

I was aiming for the prior’s home village of Grimley, which is on the other bank of the river four or five miles upstream from Worcester and about halfway to the next bridge. I had looked at the map – closely, I thought, but not closely enough – and had reasoned that I would be able to cross by means of the weir at Bevere Island. My reasoning was faulty; I could not even get to the weir, let alone cross it (which I wouldn’t have been able to do anyway, it being a weir without a bridge).

The annoying consequence was that I had to keep pedalling until I reached the first bridge, and then turn downstream to find Grimley. The annoyance was intensified by my decision to forsake the noisy road for the riverside footpath, which was picturesque and afforded pleasing views of the river – including Grimley on the other side – but was very bumpy and liberally equipped with stiles that had to be surmounted by me and bike.