Полная версия

Skylarks and Rebels

An old family photograph that my grandmother Līvija gave to me of a family wedding in Zemgale, circa 1900.

The language of my grandparents’ poetry, Latvian, is not only ancient, it is beautiful, poetic, and evocative. It was the first language I heard as a child. I can speak and write it, and I am passing it down to my children. I cannot live without the Latvian language. It is as important to me as the air I breathe. It is the deepest part of my personal identity and a link to other Latvians around the world. Russian poet, exile, and Nobel laureate Joseph Brodsky (1940–1996) wrote: “I belong to the Russian culture. I feel a part of it, its component, and no change of place can influence the final consequence of this. A language is a much more ancient and inevitable thing than a state. I belong to the Russian language.” (Poetry Foundation) I can say the same about the Latvian language: it is my spiritual home.

Latvia has been a multicultural country for centuries. Ethnic Latvians comprise its majority. Minorities include Russians, Belarusians, Ukrainians, Jews, Lithuanians, Poles, Roma, etc. Latvia’s ethnic makeup was drastically altered under Nazi and Soviet rule. Its Jewish population was annihilated during the German occupation. Later under the Soviet policy of Russification, Latvia absorbed hundreds of thousands of Russian speakers. Latvia’s Russian speaking population grew at an alarming rate under Soviet rule. This legacy remains a source of social and political tension in Latvia even today, especially in its relations with belligerent Russia.

Prior to the Soviet occupation in 1940, Rīga was a thriving port city that enjoyed trade and commerce with many Western European countries. Around the turn of the 20th century Rīga had a small British community with its own Anglican Church, St. Saviour’s, near the Daugava River. Soil was shipped from across the sea so that the church could be built on British soil. George Armitstead (1847–1912), born into a British merchant’s family, became Rīga’s mayor in 1901. Russian Orthodox churches throughout Latvia attest to Russia’s influence in the region. The tumultuous and tragic events of the two world wars left a permanent impact on Latvia, its population, and its architectural legacy.

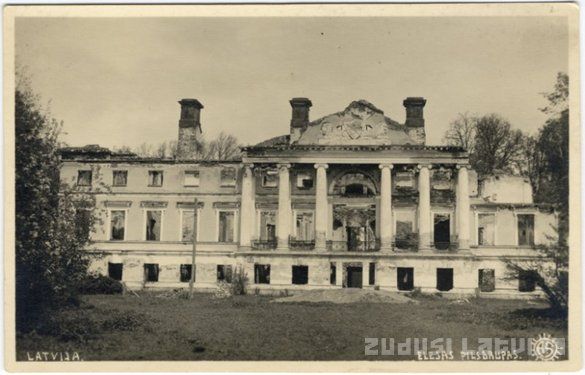

Latvia’s Baltic German population, once so powerful in Latvia, is long-gone, forced to repatriate under Hitler’s orders starting in 1939. Germans had been around in Latvia for centuries as masters and commanders and had a great effect on on my ancestors’ culture, customs, religion, character, and mentality. Not all of the influences were negative. Germans left us beautiful parks, churches, manors, and other notable buildings.

Latvia’s synagogues before World War II reflected Jewish history in Latvia that could be traced back to the 16th century. Latvian literature and Latvian folk songs have references to Germans, Jews, Roma, and Russians. Many Jews who settled in Latvia after the war emigrated in the 1970s. The region of Latgale with its distinct Latgalian dialect or language (depending on whom you ask) has also been decimated over time.

Latvia’s indigenous Liv population is nearly gone, and the Liv language on the verge of extinction. It may yet survive, thanks to the efforts of some fanatic Liv descendants. In his beautiful book of black and white photographs, Lībieši (2008), Juki Nakamura has documented the last of the Livs living in Latvia today.

“Vanishing voices”: A group of Livs in their Sunday best photographed in their seaside village Sīkrags by Vilho Setele in 1912. “Vanishing Voices” was a compelling article published in National Geographic Magazine in October 2012 about the world’s vanishing languages. Source: www.nba.fi/liivilaiset/Latvia/1Latvia.html

Latvians are “a small, thievish nation that lives in trees and eats mushrooms.” In another version we are “a small, quarrelsome nation.” Someone claimed that Winston Churchill coined this description. Others say it goes back centuries. Silly though it sounds, sometimes it describes us quite well. Our weakness is our infighting, especially in the political realm. We like to perpetuate the myth that our national character is marred by envy, jealousy, malice, and grudges. There are plenty of folk songs that seem to substantiate these claims. Supposedly we will do anything to trip up another Latvian: “Latvietis latvietim gardākais kumoss” (“A Latvian is a Latvian’s favorite morsel”), and so on. These self-deprecating comments are funny up to a point. Yet events in history speak of our ability to consolidate, especially in the face of adversity, which has been our constant companion for centuries.

As for real mushrooms, in the late summer and early fall giddy Latvians don rubber boots and head into the forest with baskets and knives in search of glorious edible fungi, of which there is an astonishing abundance. For sautéing, marinating, and drying, mushrooms like King Bolete (Boletus edulis or baravika in Latvian), Slippery Jacks (sviesta beka), chanterelles (gailene), Saffron Milk Caps (rudmiese), Russula (bērzlape), etc. thrill Latvians young and old. In the spring, fungi connoisseurs also hunt for that special delicacy, morels (Morchella sp. or murķeļi). Most Latvians have a countryside retreat where they go to enjoy the outdoors, a bit of gardening, and culinary activities like berry picking and mushroom hunting. This is a marvelous way to stay in shape while enjoying the beauty and bounty of Latvia’s nature.

Our ancestors built their homes with logs and planted oaks, lindens, and other trees around their houses for beauty and shelter. In ancient times their fortified castles on top of castle hills were constructed of timber before the advent of the crusaders. Even when the Germans started grabbing our lands, converting us to Christianity and making serfs of us, our ancestors stubbornly clung to their pagan ways and sought out oak trees, a symbol of male strength and courage, for worship and offerings. Other trees besides the oak were anthropomorphized. The linden symbolizes feminine beauty. Pērkons, our ancient god of thunder, rumbled and grumbled from his celestial perch. Our fates were determined by Laima, the goddess of destiny. Many ancient superstitions have survived into modern times, and some Latvians have sought to revive their ancestors’ pagan religion, which is deeply rooted in nature.

Latvia’s climate is similar to that of Europe’s Scandinavia. Long, dark winters with considerable precipitation—sludge in the capital, snow in the countryside, dreary rainfall—are followed by short but brilliant summers with long days and short nights. Latvia’s climate is excellent for raising crops, including grains, vegetables, fruit, and flowers. My personal favorite, the dahlia, thrives in Latvia’s temperate summers.

The relatively shallow Baltic Sea never really warms up; swimming in it is a cold but refreshing experience. With the soft, white sands of the popular seaside resort Jūrmala next to the Gulf of Rīga, the picturesque, boulder-strewn beaches of the Vidzeme coastline, and Kurzeme’s beautiful, quiet, relatively empty beaches and old fishing villages that stretch along the open Baltic Sea, Latvia’s history has been defined by its meeting with the sea. Centuries ago it attracted foreigners who sought to claim it. At the end of World War II, departing from its shores, thousands of Latvians fled in fishing boats and German ships from the Red Army to Sweden and Germany. Under the communists, most areas along the sea were off-limits to the average Soviet citizen. The beaches were fastidiously patrolled by Soviet border guards, smoothed and combed to track the footprints of anyone attempting to escape from the USSR via the sea. Today the approximately 500-kilometer shoreline is open and accessible to the public. Latvians can still fish in their waters; however, rigid European Union quotas are endangering that age-old way of life captured in Latvian folk ditties: The sea did roar, the sea did hiss, / What lies at the bottom of the sea? / Gold and silver / And some mothers’ dear sons.

The Baltics have a way of casting a spell on people who have lived there for a longer period of time. American diplomat George Kennan (1904–2005), who worked at the American Legation in Rīga in the 1930s, took note: “(Visiting Stockholm), something in the light, the sunlight, the late Northern evening suddenly made me aware of (...) Latvia and Estonia, and I suddenly was absolutely filled with a sort of nostalgia for (…) the inner beauty and meaning of that flat Baltic landscape and the waters around it. It meant an enormous amount to me. You can't explain these things." (Costigliola, Frank. “Is This George Kennan?” The New York Review of Books. Dec. 8, 2011.) Latvia’s gentle, verdant landscape dotted with gigantic boulders, many of them dubbed velnakmeņi or “Devil’s Rocks,” cast a spell on me, too, when I lived there.

Source: J. Sedols, Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vadakstes_vald

nieks_-_akmens_Ezeres_park%C4%81_2000-11-04.jpg (© CC BY 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by /3.0/deed.en)

A Latvian Folk Tale about Ezere

Several centuries have passed since that time when Ezere Manor was ruled by Baron von Nolcken. Back then it was simply called Nolcken. There was a terrace on the manor house’s east side, where each morning the baron would sit and drink coffee. From the terrace the river, the Vadakste, which formed the border (between Latvia and Lithuania—RL), was well visible. The baron was a ruthless sadist. Beneath the manor, where the baron often dined with guests, he had constructed a maze of passages. These passages connected the manor house with the chapel and the river, which had once been deep and navigable by ships. It was said that these passages had been dug by slaves. Long, deep, and gloomy, they were filled with dangerous traps. According to the baron’s instructions, secret cellars had been constructed beneath the passages to entrap hapless wanderers.

One such passage was located right beneath the terrace. While the baron entertained his guests on the terrace, beneath it people sentenced to death for minor transgressions stumbled about trying to find a way out. At a certain point in the passage a large millstone had been set into the floor. If someone stepped on the stone, it tipped, propelling the victims into a dark and damp cellar filled with the bones of other victims.

The newlywed wife of the baron’s son, the beautiful Ezere, fell into this trap, too. The young baron and Ezere had just celebrated their wedding. They and other young couples were playing the traditional game of hide-and-seek. Unsuspecting Ezere stepped on the millstone and fell into the cellar. But she was a sorceress. Outraged by what she discovered, she woke up the dead. They emerged above ground, chasing off the evil baron, and Ezere became ruler of the manor. That is how it came to be known as Ezere. (Latvian historical folk tale. Source: http://www.ezere.lv/35550/vesture1. Tr. RL)

Ghost stories are attached to many of Latvia’s old German manor houses, which remind me of the mansions of the American South. For some reason many of them feature a lady “in green” (zaļā dāma). Was there any truth to the Ezere tale? Had there once been a sadistic baron, a serial killer who had turned his manor into a house of horrors? Baron von Toll must have had a cruel streak in him as well, ordering his subordinates to roll a humongous boulder for ten years from the river to his park. Many of the old manor houses of the Baltic German landed gentry still stand in Latvia, some of them particularly ghostly in their state of neglect or abandonment.

Latvia, land of lore, boasts countless legendary “sacred” springs associated with tales of pagan worship and sacrifice. Our many castle hills inspired tales of mysterious passages and vanishing people and animals. Latvian peasants with lots of time to kill during the long, cold, dark winters spun yarns near the fire about hedgehogs becoming kings and orphans meeting God disguised as a beggar…

Groves of straight birch trees sweep the Baltic sky like gentle brushes. In the spring many Latvians tap into the sap, fermenting it for thirst-quenching, hangover-healing consumption after celebrating the summer solstice in late June. Ancient oak trees of enormous girth rise from the meadows and fields, their massive limbs and fingers providing a perch for birds, shaking down acorns in the fall for wildlife to feed on. Linden trees burst into fragrant bloom in early summer, attracting bees and other pollinators as well as humans in search of fragrant, healthy herbal teas. Latvia’s magnificent forests are full of wildlife; its mysterios bogs beckon with shiny cranberries. If our planet Earth’s biodiversity has diminished severely in the last half-century, then in Latvia it seems to be flourishing. According to Yale University’s 2012 Environmental Performance Index, Latvia was ranked the second cleanest country in the world. Paradoxically, the backwardness of the Soviet economy and agricultural system just may have contributed to Latvia’s “cleanness” and its high ecological rating. Most of Latvia’s lakes are clean and full of fish.

What kinds of creatures call Latvia’s open spaces and forests home? My people have whimsical dainas and folk songs about moose, elk, deer, bears, wolves, foxes, the gorgeous lynx, wild boar, polecats or fitchews, the hare, ermines, weasels, red squirrels with their cute tufted ears, flying squirrels, hedgehogs, badgers, otters, seals, and other animals, birds, fish, insects, and snakes, including the venomous odze (adder). The now extinct auroch or wild ox (taurs) and wisent or European bison (sūbris, sumbrs) once roamed across Latvia. Each summer storks from Africa visit Latvia to build their nests on chimneys and telephone poles; their clattering can be heard from far away. People in Latvia are close to nature, because they spend a lot of time outdoors sowing, planting, and harvesting. In the early 1990s wolves attacked and ate our beloved dog, Duksis… Latvia was a bit wild back then and still is.

Latvia is also a former battleground where men of various armies fought and died in many wars. The sounds of the skylark, cuckoo, corncrake, owl, and choruses of insects sang fleeting eulogies. Today it is hard to imagine that Latvia could sustain so much bloodshed, destruction, and human displacement in the conflicts of the previous century. Its quiet forests remind me of the quiet and peace of great cathedrals, and my generation has no personal recollection of these conflicts. Yet war has a way of rippling into the future. We are part of its aftermath. In the 1990s, when I first visited Kurzeme, I was enraptured by its beauty and sobered by thoughts of the war, the streams of refugees, and the tragedy of Latvia in the 20th century.

Latvia’s highest mountain, Gaiziņš, which rises a mere 312 meters above sea level in the central part of Vidzeme, is more like a hill. The first time I climbed up its slope in the summer, I giggled. This was it? Our famous Gaiziņš “mountain”? However, the view from the top was breathtaking. Latvia’s countryside provides no points of dramatic beauty like the Swiss Alps or New Hampshire’s White Mountains. Its beauty is soft, a verdant velvet of rolling hills, forests, meadowlands, fields of ripening grain, and blue lakes that reflect a bright blue northern sky. Dusty roads cut through the scenic landscape dotted with old wooden buildings.

Lovely lakes, some quite deep like Dridzis in Latgale (65.1 meters), and smaller waterways add sparkle to the green landscape. Two large rivers wind through Latvia: the Daugava (“river full of souls”), emerging from the east in Russia and Belarus and flowing into the Gulf of Rīga near the Latvian capital; and the Gauja, which unfurls in the central part of the region of Vidzeme, loops northwards and then snakes south, depositing its waters into the gulf as well. Living in Rīga, the Daugava became a part of my life; I walked across it many times, always admiring the reflection of Rīga’s centuries-old skyline. The only other city to occupy such a meaningful place in my identity is New York.

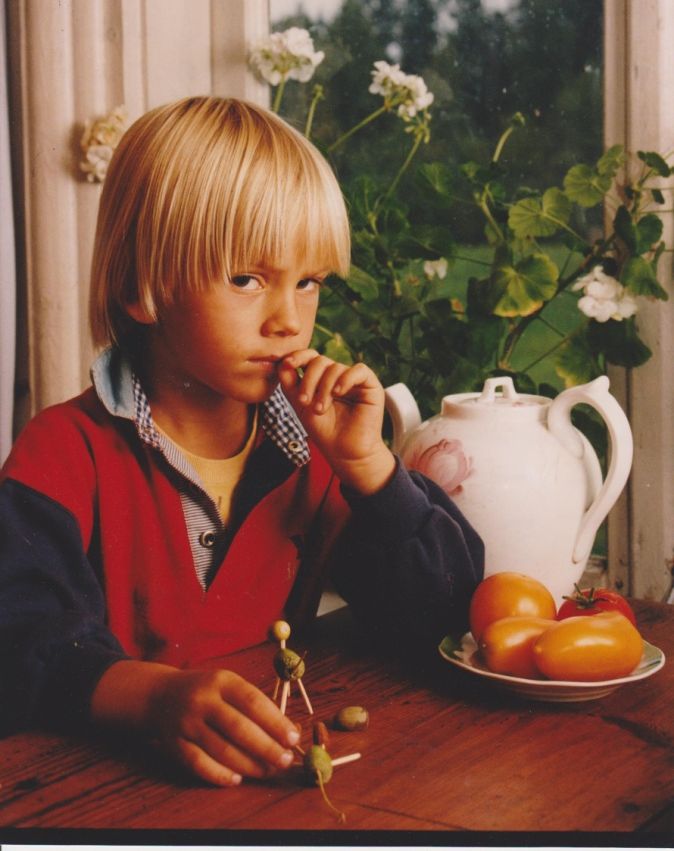

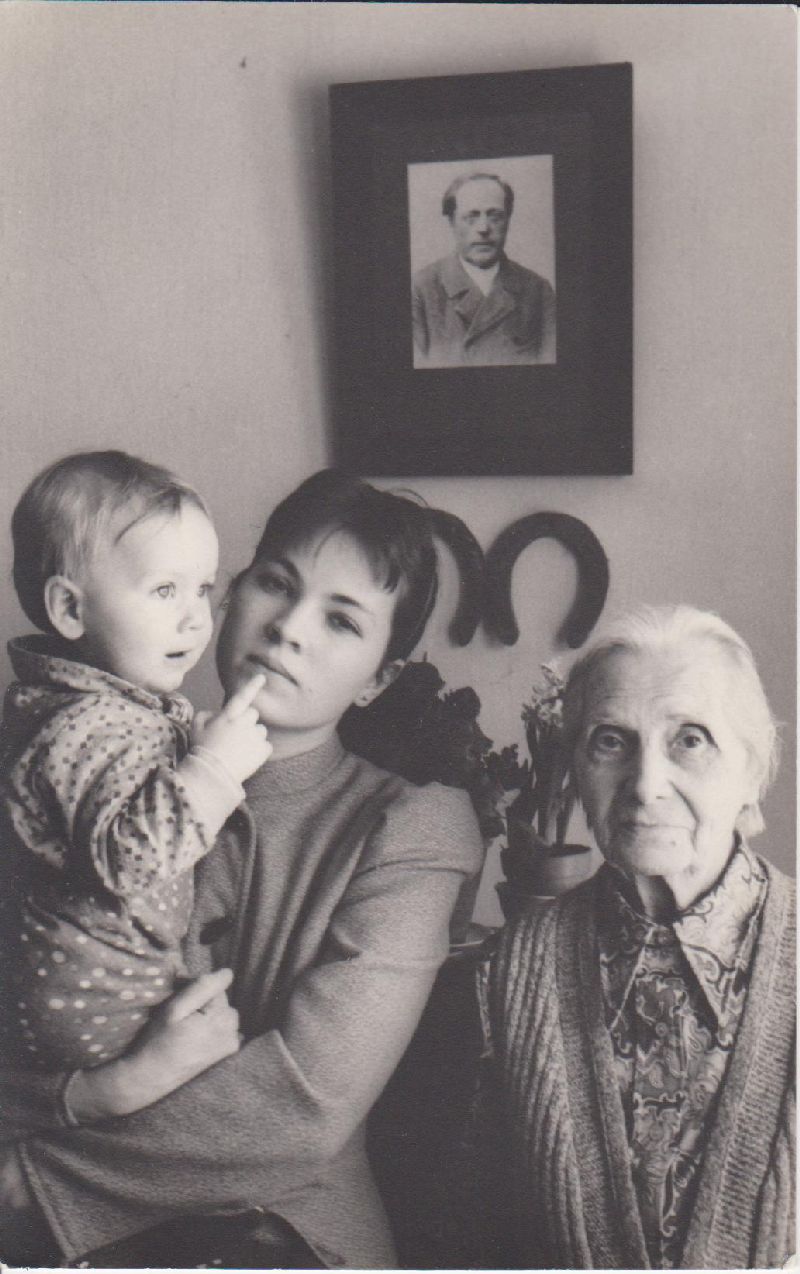

Four generations in Olaine, Latvia in 1984: on the wall a portrait of my great-great-grandfather Jānis Rumpēters (1831–1915); my paternal grandmother Emma (born Lejiņa) Rumpētere; my son Krišjānis and I. (Photo by Andris Krieviņš)

The Latvian economy has changed over time. Agriculture continues to play a big part in the life of Latvians, and farming seems to be second nature to them. As elsewhere, the Industrial Revolution would bring enormous changes, as new industries and factories attracted laborers from the countryside to the city. Then World War I razed much of Latvia’s industry, mostly concentrated in Rīga, but there was an incredible resurgence and a rebuilding effort in the brief years of independence between the two wars. Forestry remains a precious resource and export for Latvia. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, most Soviet era industrial plants, including those based on Latvia’s pre-war industry (such as VEF―Valsts Elektrotechniskā fabrika), were privatized, split up, and sold off, with the loss of thousands of manufacturing jobs. Today Latvia’s farmers struggle to compete within the European Union’s vast agricultural market, proving that each era brings a new set of challenges for my people to deal with.

Latvia has been a democratic parliamentary republic since 1991 and joined the European Union in 2004. Like many countries that once fell under the Soviet sphere of influence, it has deep-rooted problems, such as corruption, financial crime, a lagging economy, weak governmental oversight, and regional disparity.

There are wonderful positives about Latvia: its status as the 2nd cleanest country in the world; its status as the most beautiful country in the world (according to the Daily Mail of the United Kingdom, May 14, 2012, and other sources); the success of its cultural endeavors, including world class choirs (Kamēr, Balsis, The State Academic Choir Latvija) and opera singers of international fame (Elīna Garanča, Maija Kovaļevska, Kristīne Opolais, and others); its brilliant conductors (Mariss Jansons, Andris Nelsons), etc. Famous violinist Gidon Kremer grew up and went to music school in Rīga. Ballet legend Mikhail Baryshnikov was born and raised in Rīga. Latvia’s artists regularly participate in the world’s biennales. The music of Pēteris Vasks (b. 1946), Ēriks Ešenvalds (b. 1977), and other Latvian composers can be heard on American classical radio stations. Vasks’ wife Dzintra Geka has made a name for herself promulgating via film and books the tragic stories of the children of Latvia deported to Siberia. In 2014 Rīga was the European Capital of Culture.