Полная версия

Skylarks and Rebels

ibidem Press, Stuttgart

Table of Contents

Introduction

Hello! Sveiki! (Latvian) Labas! (Lithuanian) Tere! (Estonian)

With gratitude

Glossary

Prologue: A Country the Size of West Virginia

A Latvian Folk Tale about Ezere

PART ONE: New Jersey Latvian American Girl and Trimda (Exile)

Hillside Haven

Programmed for Latvia

Catskill Summers

Latvian Bohēma

PART TWO: Latvia as a Battlefield—World War II

The Two Wars’ Long Shadows

Refugees, Immigrants, Exile

Opaps (Paternal Grandfather)

Omamma (Paternal Grandmother)

Dimmed Lights (Great-Grandparents)

Pēteris and Dārta Bičolis of Sēlija

Augusts Jānis and Amālija Rumpēters of Vidzeme

Great-Grandparents Antons and Matilde Lejiņš of Northern Vidzeme

Enemies of the Soviet State: A Latvian Hero and His Bride

Victims of Soviet Repression: Photographs of Velta (b. Rumpētere) and Eduards Rapss

PART THREE: Return to Terra Incognita

Crossing the Border

The Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic

Cold Light in Rīga

3/5 Raiņa bulvāris

Latvian Poster Art

Farewell, Latvia!

Interlude (November 1980–September 1981)

PART FOUR: The 1980s

Tuk! Tuk! I’m Home!

Rīga (1201)

Letter dated January 4, 1983 to my parents in New Jersey

New Beginnings at Krāmu iela 10/4a, Tel. 211951

Letters

Excerpts from a letter dated January 15, 1983 to my parents

Rīga up Close

A Strange Incident at the Rīga Bourse

Puppets and Masters

Practicum

Zeppelin: Rīga Central Market (Central Kolhoz Market)

Desecration

Art in the Forest

“Old Friends” (Bookends) and the Magic of Ramave

1983: A Wedding in Snow

In-Laws

Comme des Communistes: Trying to Look Chic in a Command Economy

The Controller Is Coming!

Leniniana

“Communism’s Victory is Inescapable!”

Fresh Air in the Latvian Countryside

Ghosts

Judenfrei: Tamāra and the Jews of Latvia

Roosters and Cats in Old Rīga

Jūrmala

New Life

Mushrooms

The Gift

Ad Astra per Aspera: Gunārs Astra, Our Bright Star

Crippling Humility

“Traitors”: Remnants of Bourgeois Nationalism

Russian Boots on the Ground

Kurzeme: Strazde—Spāre—Pope—Ventspils—Ēdole—Alsunga—Kuldīga

Vot, vot, Comrade Ilmarovna!

Entertainment

1984: A Ruckus at St. Peter’s

The Water Breaks

Baby Blues

Maskačka’s Edžus

A joke about Rīga’s monuments.

1985–1986 / Squeezed

1985: The Red Spot

1986: Our Rage against the Machine: Chernobyl

Is It Easy to be Young? Latvian Youth Behind the Iron Curtain

1986: Hoping for Change

PART FIVE: The Thaw

Klāvs

1987: Depression

Sandy*

1988: “Rīga Retour”

1987: Helsinki-86; “Queen Latvia is Awakening”

1988: Life in an Approximation

More on Approximation

The Beginning and End of Indian Village

1988: The Latvian Flag

June 14, 1988

Labvakar! (“Good Evening, Latvia!”)

1988: Baltica

1988: Bearslayer

Bearslayer

A Stronghold in the Fatherland

The Latvian Popular Front

Litene

Light in Darkness

1989: “Come out, justice, from your metal coffin”

“Sex scandal”

X-Rated

A Death in Piebalga

1989: The Human Chain

Too Good to Be True?

The Fall of the Berlin Wall

1990: A New Beginning

Together in Eternity

Together in Song

Summertime

First day of school

It’s a boy!

The Lenins Come Down

1991: The Barricades, January 13–21

Dedovshchina: “Hazing”

Fragile democracy, frail baby

1991–1992: A Dream by the Gauja

“And It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue”

PART SIX: The 1990s; Freedom; Farewell.

The Russian Mafia

Latvia: The Most Beautiful Country in the World

*

About the cover page illustration and its back (above): A birthday wish dated September 24, 1967 from two Latvian Soviet political prisoners, Viktors Kalniņš and one Jānis (surname unknown), to their prison mate, Estonian freedom fighter Enn Tarto (born in September 1938), on his 29th birthday in a prison camp in Mordovia. The card depicts the Latvian Freedom Monument, the Daugava River, and Rīga. The inscription on the back reads: “Greetings to Enn on his birthday! We wish you all the best in the future and the fulfillment of all your dreams and hopes. 24. IX. 67. Mordovia. Viktors. Jānis.”

Illustration courtesy of Enn and Piret Tarto.

The coat of arms of the Republic of Latvia designed by Rihards Zariņš and adopted in 1921. Source: Wikimedia Commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Coat_of_arms_of_Latvia.svg)

Country denoted for them not just a particular geographical environment known and cared for in every detail, but a cultural space alive with stories, myths, and memories. It furnished food, drink, and shelter, as well as every sort of sustenance for the mind and spirit.

—Iain McCalman, The Reef

Live Free or Die.

—The official motto of the US state of New Hampshire as coined by General John Stark

Deeper meaning resides in the fairy tales told to me in my childhood than in any truth that is taught in life.

—Friedrich Schiller

If you can’t resign yourself to leaving the past behind you, then you must recreate it.

—Louise Bourgeois

Photograph of a stopa sakta or crossbow fibula, traditionally worn by men in the eastern Baltic area, courtesy of Andris Rūtiņš, BalticSmith.com.

Cīrulīti mazputniņ, negul ceļa maliņā.

Rītu jāsi bargi kungi, samīs tavu perēklīti.

Samīs tavu perēklīti, iecels tevi karietē.

Iecels tevi karietē, novedīs vāczemē.

Novedīs vāczemē; tur tev liks mežā braukt.

Tur tev liks mežā braukt, tur tev liks malku cirst.

Kad tu malku sacirtīsi, tad tev liks guni kurt.

Kad tu guni sakurīsi, tad tev liks bruņas kalt.

Kad tu bruņas nosakalsi, tad tev liks karā iet.

•

Skylark, little bird, don’t sleep by the roadside.

Tomorrow the harsh masters will come; they’ll crush your little nest.

They’ll place you in their carriage and take you to Germany.

They’ll drive you into the forest and make you chop a lot of wood.

When you finish chopping, they’ll make you build a fire.

When you build the fire, they’ll make you hammer armor.

When you finish the armor, they’ll make you go to war.

(Old Latvian folk song)

A map of the three Baltic States, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, which lie on the eastern rim of the Baltic Sea. Source: Wikitravel (author Peter Fitzgerald) http://wikitravel.org/shared/File:Baltic_states_regions_map.png

With love to my children: Krišjānis (1984) and Jurģis (1990), born in Soviet-occupied communist Latvia; Tālivaldis (2001) and Marija (2005), born in the land of freedom and democracy, the United States; and to my grandson Teodors (2014) and my granddaughter Kirke (2016), both born in the free and independent Republic of Latvia.

In loving memory of my grandparents, Augusts and Emma Rumpēters and Jānis and Līvija Bičolis, who passed on the light and love.

I also dedicate this memoir to Latvians, Lithuanians, and Estonians around the world.

“How many years can some people exist

before they're allowed to be free?”

—Bob Dylan

“How could you live in communist Latvia?!”

—A question the author has often been asked.

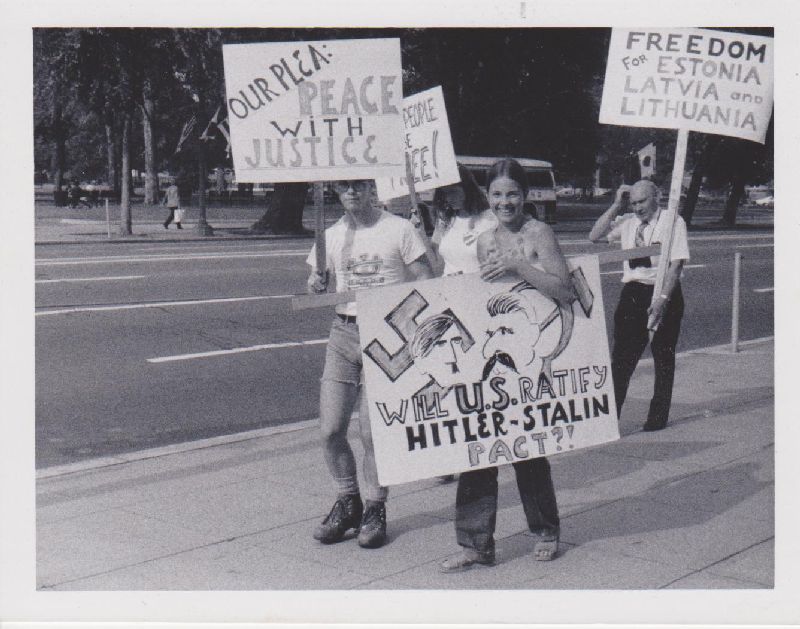

Sweet sixteen: My older brother Arvils and I in Washington, DC in August 1976 to remind people of the notorious Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact signed by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union on August 23, 1939, and to protest the ongoing Soviet occupation of Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia. For many years the Baltic exile community remained strong, politically active, and dedicated to the cause of restoring the Baltics’ independence. (Family photo)

Introduction

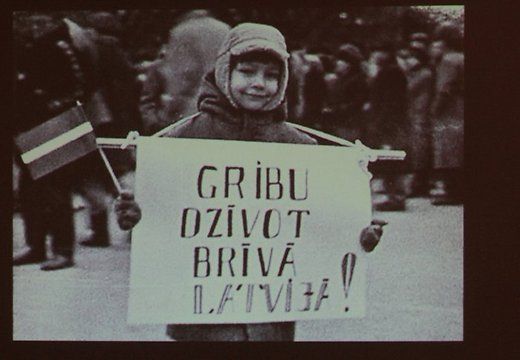

“I want to live in a free Latvia!” A photograph from 1991 and the “Barricades” time. (Unknown photographer)

These are the memories that I carried around inside of me for years after I left Latvia in 1999. For a while I simply could not find the time to sit down and write; I bore two more children into the world, and their needs consumed me. When my daughter was born in 2005, I realized it was “soon or never.” Numerous unsuccessful job searches seemed to signal the urgency to turn to writing and try to capture the end of a dark era in Eastern Europe that many of my American compatriots knew little about. I had been there and lived through my “fatherland” Latvia’s last decade under the brutal Soviet Russian occupation, but not that many people knew where Latvia was or what life in the Soviet Union had been like. And in spite of independence, the future of Latvia, Latvians, and our beloved language, the key to our identity, remained clouded by uncertainty and tough economic times. This situation added to my sense of urgency. Nor was I getting younger. Each year seemed to dissolve into the last, compressing my sense of time.

While I dug into my memory, Latvians continued to emigrate from their native land in droves. Each year, as I became one year older, Latvia’s population diminished, with more people dying off than being born. There were many reasons for this, including the distant events of World War II and the Soviet occupation, which had a long-lasting, detrimental impact on the Baltic States. As I wrote, people of great significance to Latvia passed away, leaving a void. For a small nation each individual carries great weight. The oldest members of the former Latvian exile community (that is, my parents’ generation, which experienced the war) are dying off these days. Latvia’s demographic situation has become precarious. My story is about identity, language, patriotism, love, loss, and an archetypal landscape; it’s also about being young, idealistic, and fearless. I was full of curiosity, longing, and love when I traveled to the “fatherland” (tēvzeme in Latvian), the land of my ancestors, the country my grandparents were forced to leave due to terrible events beyond their control. My story will resonate with the descendants of Balts and East Europeans whose countries ended up behind the Soviet Iron Curtain after the war, whose families became refugees, and who sought to preserve their ethnic identity while becoming part of America. This is why I feel a deep kinship with my fellow Balts and with Poles, Ukrainians, Czechs, Hungarians, Jews, etc. Some of us still wonder where home is.

In this book I have retained diacritical marks to pay tribute to my mother tongue. Latvian, a very old Indo-European language, is the most basic and most important component of my identity. The United States of America is a country of immigrants, and Americans have come to accept all sorts of foreign names as part of their heritage. For this I love America.

As a first-generation American I am well integrated but not assimilated. I have no shame in speaking to my children in Latvian with Americans within earshot (I hope my fellow citizens do not consider me rude for doing so). I discovered that my fellow hockey, soccer, and school parents are a tolerant bunch. My Latvian language is a gift passed down through scores of generations, and I have no intention of breaking “the chain” of continuity. Our open American society makes me feel accepted. Our children’s American public schools display Latvian flags alongside other flags representing the countries of their students’ origins. What a great way to nurture American patriotism through the acceptance of its nation’s amazing diversity!

I enjoy reading the names on the jerseys of the hockey players we watch on the ice: it is also in those names that the diversity of America the Beautiful is revealed. Chinese, Finnish, French, German, Hungarian, Italian, Latvian, Polish, Russian, Swedish—names from all over the world—reflect the American nation’s history and essence. Life in Latvia in turn exposed me to its multi-cultural history. I became acquainted with Russia’s rich cultural and dramatic historical legacy and influence, even though in the Soviet era its positive effects on Latvian history were, mildly put, exaggerated and far-fetched. I was able to see a bit of Estonia and Lithuania while living in Latvia and realized again just how strategically important the relationship between the Baltic States is. In the 1990s I was able to easily travel to other countries in Europe. Stockholm, Amsterdam, Copenhagen, Salzburg, Helsinki, Vienna, Venice… So many beautiful, wonderful, and different destinations could be reached from Latvia within a couple of hours of air travel. Living in Europe was exhilarating, and it made me realize that I was an amalgam of European and American influences.

Although I am Latvian, this book is also dedicated to Latvia’s Baltic neighbors, Lithuania and Estonia. The Latvian and Lithuanian (Baltic) languages are closely related. Old Prussian, now extinct, was once part of this language group. Estonian, the language of our hardy neighbor to the north, is a Finno-Ugric language and not at all like Latvian or Lithuanian. The Baltics are a distinct region of northeastern Europe with unique histories, cultures, and landscapes. My parents always spoke of Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia as if they were members of a close family that had suffered the same fate in the 20th century.

Hello! Sveiki! (Latvian) Labas! (Lithuanian) Tere! (Estonian)

I am very proud of the fact that I know part of my lineage, and that I can trace my roots back in time to places on the map of Latvia: Vidriži, Aloja, Birži, Augstkalne... There are some places in the United States that bear names of Latvian origin, like Livonia (Michigan), Riga (New York), and Riga Lane (on Long Island). We Latvians get a big kick out of this. I am proud of my two flags: our Latvian red-white-red flag and the Star-Spangled Banner of the United States of America. Latvian Jewish artist Roman Lapp’s hand from his exquisite series of drawings, “Hands for Friends,” is a perfect illustration of what I am. These colors symbolize my belonging to two very different cultures, which have made me the person that I am. One flag represents an obscure region of the Old World; the other symbolizes the New World and the United States and its break from the colonial fold. The United States of America remains the world’s brightest beacon of freedom and democracy: it has granted asylum to persecuted people from around the world. Among those were the Baltic refugees after World War II who could not return to their homelands on account of the Soviet occupation. My dual identity has undoubtedly enriched me.

I love the American motto “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness” from the United States’ Declaration of Independence. These words are loaded with meaning and connotations, especially when I think about the other half of my identity—the Latvian side. Latvia’s quest for life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness lasted a very short time, commencing in 1918 and coming to a violent end in 1940 with the Soviet invasion. While others rejoiced, World War II did not end happily for the Baltic States: for nearly 50 years these nations would be brutally oppressed by the Soviet communists. My grandparents barely escaped the “Russian bear.” So many Latvian lives were lost in the 20th century, that it is a wonder that our nation survived into the 21st century.

I spent 17 years in Latvia—from late 1982 until March 1999. Part of that time was under the Soviet Russian occupation (until 1991). My charmed youth in the United States propelled me to the USSR in a strange state of euphoria and fear. I think that basic American freedoms, the American way of life, and my exposure to a lot of culture from an early age—art, music, literature, theater, and cinema—went a long way in keeping me “charged” in the depressing Soviet era, when life was lived as if in an aquarium. American popular culture and humor also strengthened me for what I was to endure in communist Latvia. “Hogan’s Heroes” with Colonel Wilhelm Klink and Sergeant Hans Schultz had made us Latvian Americans laugh (although the Nazi occupation in Latvia had been exceedingly brutal and deadly). Totalitarianism would reveal itself to me in all its dark and dreary colors.

The words of many American and British rock songs would serve as a kind of buffer between my open and inquisitive mind and the oppressiveness of Soviet reality in the 1980s. “Where are you goin’ to, / What are you gonna do? / Do you think it will be easy? / Do you think it will be pleasin’? / (…) / It’s my freedom, / Don’t worry about me, babe…” (Steve Miller, “Living in the USA”) Unlike my compatriots in occupied Latvia, as an American citizen I had the freedom to travel, and I never took this freedom for granted. As soon as I was old enough, I wanted to get out of the house and see new places. First on the list was Latvia, which our family and Latvian American society had been talking about for years. Fantastically, my experience there would correspond with history in the making: “The present now / Will later be past / The order is rapidly fading…” (Bob Dylan, “The Times They Are A-Changin’”) You’re young only once. Pumped up by the energy of the music I listened to and bored out of my mind by American suburban life, I felt I was ready for anything. Even adventures in a place that US President Ronald Reagan would deem “the Evil Empire.”

Because so little was known about the Baltic countries during the years of the Soviet occupation, we were used to hearing many strange questions in the United States. For instance, my friend Gerry at Parsons School of Design wanted to know if people in Latvia wore clogs. “Is Russian Latvia’s official language?” “Are you Latvians Russian?” This obsession with Russia grated on my nerves. Luckily, the Baltic States have clearly emerged from Russia’s shadow, with many of my fellow Americans now recognizing the names of our countries. After independence in 1991, Latvian, Lithuanian, and Estonian athletes have been winning medals at the Olympic Games to the cheers of Balts all over the world. (For example: Latvians Martins Dukurs [SILVER, skeleton, 2010 Vancouver] and Māris Štrombergs—aka “The Machine” [GOLD, BMX, 2008 Beijing; GOLD, BMX, 2012 London]; Lithuanians Rūta Meilutytė [GOLD, breaststroke 100 m, 2012 London] and Laura Asadauskaitė [GOLD, Modern Pentathlon, 2012 London]; Estonians Erki Nool [GOLD, decathlon, 2000 Sydney] and Heiki Nabi [SILVER, Greco-Roman wrestling 120 kg, 2012 London], etc.) After years of being forced to compete under the despised Soviet flag, Baltic athletes could finally compete under their national colors and hear their anthems fill stadiums around the world.

As an American in Soviet Latvia in the 1980s, I was a curiosity and a mystery. My Latvian heritage did not seem that important to anyone; it was the fact that I was American that was initially so intriguing to the people I encountered. Yet most of them were too scared to ask questions. Most Latvians could not understand what I was doing in Latvia in the first place, and this nurtured wild rumors. CIA, KGB… “Why on earth was I lingering on a sinking ship?” was the question I heard from time to time in the early eighties. (If the ship was sinking, that was a good reason to hang around, I thought.) As time passed, the curiosity dissipated; people lost interest when they grew used to my presence. (Rīga is not that big.) My strange haircut—an extreme mullet of sorts—grew out, and I blended in. Soviet leaders came and went, the tide of history changed, and the great “upheaval” began. A trickle at first but then building into a torrent of emotion and daring protest … The late 1980s were an unforgettable historical period of “national awakening” in Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia, prompted by Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s policies of perestroika and glasnost after decades of repression, the numbing beat of Soviet communist ideology, and economic stagnation under the Politburo’s heavy, all-controlling paw.

In my book I often refer to Latvia as the “fatherland,” because Latvians traditionally refer to their native country this way. “I placed my head on the boundary / To defend my fatherland; / Better that they took my head / Than my fatherland” are the words of an old Latvian daina or folk poem/song. You won’t find the word “motherland” in Latvian dainas and literature, but in artistic and especially sculptural representation Latvia is depicted as a woman. Latvia’s Freedom Monument in Rīga is the figure of a woman—the mother who gave us life and defends her children, as we should defend her. The word tēvzeme evokes feelings of patriotism and protectiveness. Our history has been marked by so many tragedies, that we all feel protective of our beautiful country.