Полная версия

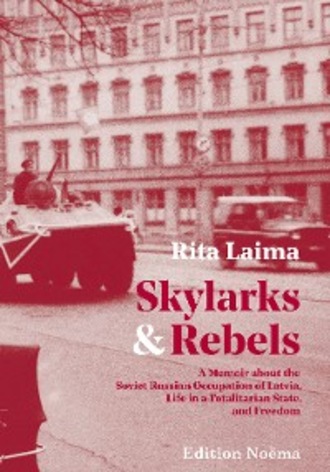

Skylarks and Rebels

As the mother of three sons, I have thought a lot about all the Latvian boys and men who gave their lives for the idea and reality of a free and independent Latvia (in the Latvian War of Independence [1918–1920] and during WWII), and about those who were forcibly conscripted into foreign armies (Nazi Germany’s and the Soviet Union’s Red Army, for example) and died in wars they should never have been a part of. Their countless names are impossible to list. Their bones are scattered across Latvia, Russia, Belarus, Poland, Germany, and elsewhere. Some of Latvia’s veterans from World War II still survive, cheered and cursed, their role in the last war misunderstood. The remnants of the Latvian Legion fought in the “Kurzeme Fortress” (also known as the “Kurzeme Cauldron”) against the advancing Red Army in World War II, helping thousands of Latvian refugees, including my grandparents and parents, to escape across the Baltic Sea to freedom. We Latvians have a duty to explain our complicated history, in which allegiances were forced upon us at gunpoint.

I also reflected on the women of Latvia—mothers, sisters, daughters, sweethearts, and wives who had to hold Latvia together with their bare hands and survival instinct. In the early 1920s National Geographic reporter Maynard Owen Williams visited war-torn Latvia and wrote: “[… This country] owes a heavy debt to its women, who drive the wagons, harvest the flax, pile up the grain, tend the cattle, sweep the streets, pull the carts, run the hotels, tend the street markets, keep the stores, shovel the sawdust, and juggle the lumber.” (Williams, Maynard Owen. “Latvia, Home of the Letts.” National Geographic Magazine October 1924) My grandmothers were typical Latvian women: stoic and ingenious, patient and persevering. One led her children out of harm’s way on a perilous flight across Europe from Stalin’s “Red Terror.” The other remained behind, cut off from escape by circumstance and responsibility: she and her young sons (my uncles) were among the millions of captives caught behind the Soviet Union’s Iron Curtain.

The Baltic States’ geography has not been kind to its human populations. Numerous waves of war leveled much of what human hands built in the Baltic lands. Those busy hands went back to work time and time again. Despite these cycles of destruction, my people survived, and they are a fascinating bunch. Latvia, shaped like a peasant’s clog, is a repository of stories of tragedy and remarkable resilience: one only has to start digging, reading…

Ultimately, it is many people who made this book possible. My parents Baiba and Ilmārs Rumpēters and my grandparents, Līvija and Jānis Bičolis, and Augusts Rumpēters, instilled in me a deep love for the Latvian language and our cultural legacy. In my youth I basked in the light of my parents’ friends, writers, poets, painters, and musicians, most of whom have passed away by now. I mourn their absence. My children, Krišjānis and Jurģis (born in Latvia), and Tālivaldis and Marija (born in the United States), made me realize how important it was to tell my story and to document a decade of Latvia’s history under totalitarian oppression. My friends, especially in Latvia, helped me with my story by remembering certain details. The terrible suffering of the populations of Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia in the last century was also a reason for working on my memoir. For too long the Baltic peoples had suffered without a voice.

A bit about my work on this book: I did much of my research online; I have strived for accuracy but am not a historian; and this is a memoir. I wanted to give my people a voice. I had to translate just about every source from Latvian myself (marked as Tr. RL). It is an endeavor of creative non-fiction. Many of the subjects that I mention can and should be pursued separately. The Nazi German and Soviet Russian occupations of the Baltic States deserve continued serious study. My book is laid out in such a way as to introduce the reader to my youth, which paved the way for adventures in my “fatherland.” I felt it was important to provide historical background information about Latvia in the 20th century; after all, events there explain why I was born in the United States.

So welcome to Latvia, a place I spend a lot of time thinking about, mainly because family and friends live there, and I think I would like to go back. My story is about being bicultural and exploring my family’s European roots. It is also a memoir about Latvia in its last decade as a satellite republic of the militarily mighty and fearsome totalitarian state, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. In that unhappy union Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia, independent and thriving countries before World War II, were reduced to the status of occupied provinces and nearly erased from world memory. I had the privilege of being in Latvia to witness firsthand the last decade of their oppression come to a much awaited end, as the “the Evil (Soviet) Empire” collapsed, and freedom was restored. Today that freedom is under threat again both from the outside and from within, and lessons learned in Latvia have provided a perspective on troubling times in Europe and, much to my surprise and dismay, in the United States.

Rita Laima

With gratitude

Gunārs Astra, Lidija Doroņina-Lasmane, and Juris Ziemelis: Their courage will always be an inspiration.

The Cultural Foundation of the World Federation of Free Latvians for its financial support

Toms Altbergs

Edmunds (“Edžus”) Auers—For his mother’s pastries and tea, for sharing his precious books from the pre-war era with us, and for all the Soviet jokes and many laughs

Tālivaldis Bērziņš for Tālivaldis Augusts and Marija Līvija

Parsla Blakis for her unwavering enthusiasm

Jānis Borgs

My mother Baiba Bičole for reading Latvian folk tales to me when I was little

Kārlis Dambītis

Sarma Dindzāne-Van Sant

Olģerts Eglītis

Mārtiņš Grants

Ēriks Jēkabsons

Tija Kārklis

Arvis Kolmanis

Andris Krieviņš for Krišjānis and Jurģis and the beautiful photographs

Ēvalds Krieviņš

Juris Krieviņš for showing me the beauty of Latvia

Biruta Krieviņa for teaching me the value of hard work and persistence

Uldis Liepkalns

Ivars Mailītis

Mārtiņš Mintaurs

Karu Kuu

Valters Nollendorfs

Gunārs Opmanis

Valdis Ošiņš

My wonderful Raiņa bulvāris folks: Jāzeps and Ināra Lindbergs; Tamāra Legzdiņa; Māra Lindberga and Gunārs Lūsis; Inta and Ivars Sarkans; Daina Lindberga; Linda Lūse

Composer Steve Reich for his “Music for 18 Musicians” (1974–1976) – the sound of time collapsing

Kārlis Račevskis

Baņuta Rubess

Guntars Rumpēters

My father Ilmārs Rumpēters whose prolific artistic output has always been a source of inspiration

Reverend Visvaldis Rumpēteris

Anna Rūtiņa

Uģis Sprūdžs

Alfrēds Stinkulis

Jānis Stundiņš

Valdis and Inese Supe for their friendship and hospitality in Latvia

Tekla Šaitere

www.senes.lv

Kaspas Zellis

Mārtiņš Zelmenis

Ilze Znotiņa

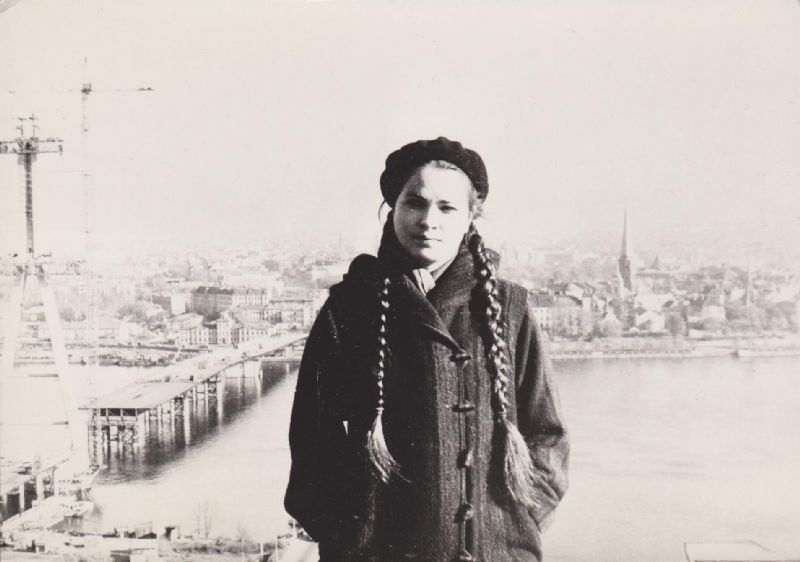

October 1980: My first time in Latvia (then the Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic) visiting as a 20-year-old art student. This photo was taken on the roof of the 22-story Press Building (completed in 1978). The Press Building housed the editorial offices of most of Latvia’s newspapers and magazines in the Soviet era. Construction of a new suspension bridge across the Daugava River is visible to the left. The work was completed the following summer (1981). The old floating pontoon bridge was eventually dismantled. On the day of this photo shoot I was painfully aware that my time in Latvia was running out. (Photograph courtesy of Gunārs Janaitis)

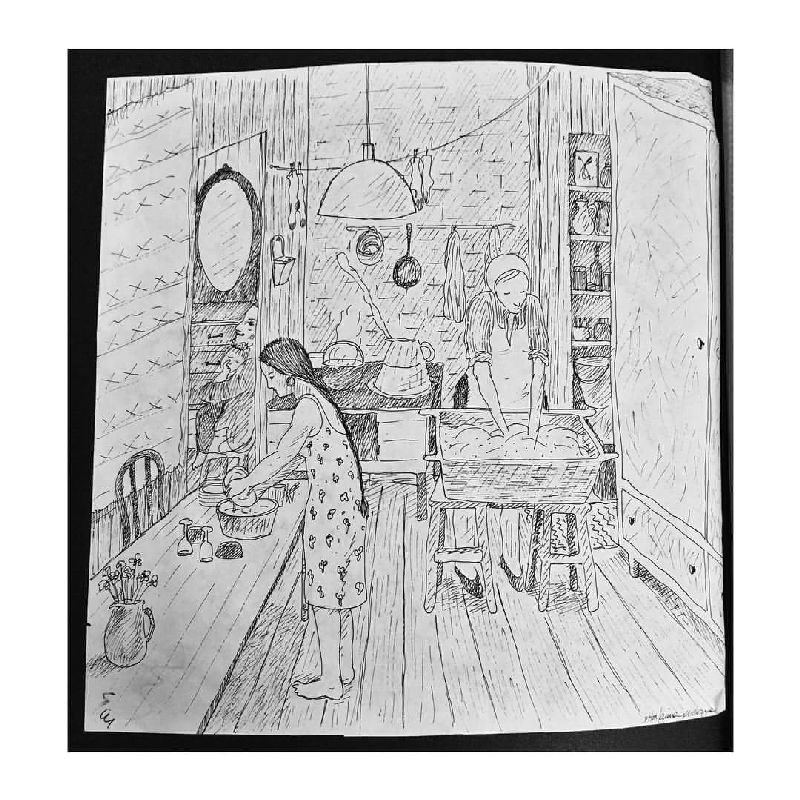

Latvia was and remains for me both a reality and a dream. This scene that I drew in the 1980s of our everyday life in the Latvian countryside in Piebalga—doing the dishes, baking bread, taking care of the children—is now a distant memory of something lost and something gained.

Storks in the Latvian countryside in summer. (Photo by Juris Krieviņš)

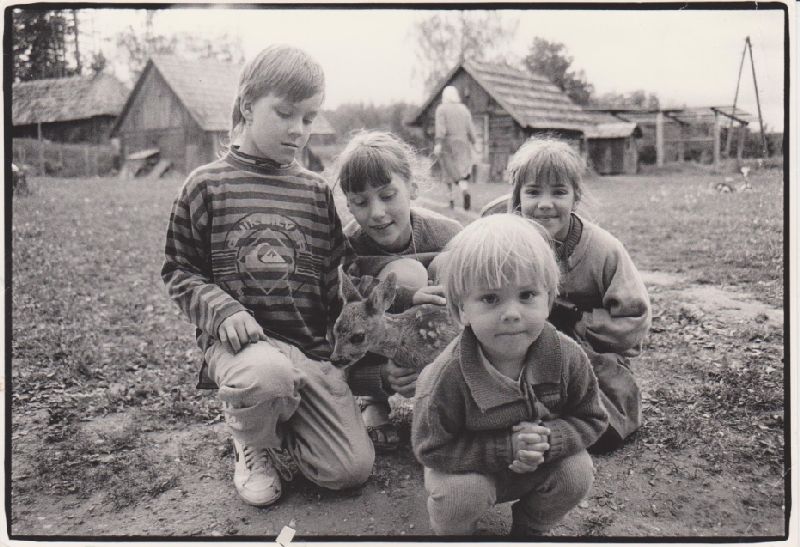

Fond memories of life in Latvia: My sons Krišjānis and Jurģis with their cousins, Elīna and Alise, and a baby deer that their father rescued and raised on our farm in northern Latvia. Their “Omīte” (grandmother) Biruta Krieviņa can be seen walking to the barn, where she kept cows, pigs, and poultry. (Photo by Andris Krieviņš, 1992)

Glossary

Blats—A word from the Soviet era in Latvia that describes the system of connections, favors, and “who you know” in a centralized, impoverished economy, in which stores carried few attractive goods, and good services were hard to come by. For instance, if someone said, “I have blats at the butcher shop on Blaumaņa iela,” it meant “I know someone at the butcher shop on Blaumaņa iela who can get me some quality meat’” (unavailable to walk-in customers). My father-in-law had this kind of blats at a butcher shop. He took portraits of the manager’s family events and was reciprocated with good cuts of meat, which he shared with us. The decades-long system of blats promoted favoritism and spawned nepotism and corruption, problems that Latvia and all post-Soviet societies struggle with today. It also taught a part of society to calculate their relationships.

Cheka / chekist—The Soviet secret police, better known as the KGB. A chekist is a KGB operative.

Eastern Europe—I use the term Eastern Europe to describe the countries that found themselves behind the so-called Iron Curtain and under Soviet communist influence after World War II.

The Free World—A term used during the Cold War to describe countries with democratic political systems, freedom of speech, and free market economies, namely the United States, Canada, and Western Europe (as opposed to the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe).

Iela—The Latvian word for street

The Iron Curtain—“The political, military, and ideological barrier erected by the Soviet Union after World War II to seal off itself and its dependent eastern and central European allies from open contact with the West and other noncommunist areas. The term Iron Curtain had been in occasional and varied use as a metaphor since the 19th century, but it came to prominence only after it was used by the former British prime minister Winston Churchill in a speech at Fulton, Missouri, US, on March 5, 1946, when he said of the communist states, ‘From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the Continent.’” (Encyclopedia Brittanica)

Laima—The Latvian goddess of fate and fortune. Ej, Laimiņa, tu pa priekšu, / Es tavās pēdiņās, / Nelaid mani to celiņu, / Kur aizgāja ļauna diena. (An old Latvian daina, which translates as: “Walk, Laima, ahead of me, / I’ll walk in your footsteps, / Don’t let me go down the path / Of the bad day.”

Trimda—The Latvian word for exile. The word trimda stands for all the Latvians who left Latvia as political emigrants during World War II and then convened abroad to establish a temporary alternative Latvian society. The aim of the exile community was to preserve Latvian identity abroad while engaging in political activism to speed up the collapse of the Soviet Union. Trimda Latvians founded congregations, bought or built churches, established schools and camps for their children, published books, read their own Latvian language newspapers, organized concerts, theater performances, art exhibits, and other social activities, striving to preserve the memory of Latvia and the Latvian language and culture. The Soviet Latvian authorities mistrusted trimda Latvians and initiated smear campaigns against some of its leaders.

Prologue:

A Country the Size of West Virginia

THIRD ELEGY

Strange to hail from almost anonymous shores

in overexplored Europe where the Baltic

still hides a lunar side, unilluminated

except for subjugations, annexations

which continue unabated for centuries.

No problem for anyone to name the Nordic countries

from Iceland to Finland,

but how about the Baltic ones?

Surely one and the same language

is spoken there? If not Russian,

at least something akin to German?

You will never guess unless we unravel

the skein of Indo-European and Finno-Ugric

language families, ponder Babel

to clear up the Baltic,

and who has time for such marginal myths?

We persist with the subsoil. Grass is another

favored metaphor (trampled upon, it springs back),

or limestone cliffs filed away by gales

yet undefiled, withstanding millennia.

It is strange to hail from the dark side of the moon

while supposedly we inhabit the same planet.

There are Third World pockets inside Europe

one tends to overlook, anonymous shores

marked with an x or a mental question mark.

If only you incline in the Baltic direction,

you begin to hear the dirge of a beehive

and perceive in underwater outline

an amber chamber built with pollen of grief.

Ivar Ivask. Baltic Elegies.

Norman, Oklahoma: World Literature Today, 1987.

Translated by Valters Nollendorfs

So let it be known: my family hails “from the dark side of the moon” and “a Third World pocket inside Europe,” from a country called Latvia. I am also American, born in the United States in 1960 as a child of refugees fifteen years after the end of World War II. My parents and all their predecessors were born in Latvia, as far as I know. I could claim to be 100% Latvian, but maybe there are some Liv, Estonian, Lithuanian, German, Swedish, Polish, or Russian genes mixed in there due to so many foreigners crossing Latvia over the course of history, breaching ethnic borders, and setting up camps or permanent bases on our lands, taking what they coveted and leaving the rest for my ancestors to subsist on. With all the wars and foreign occupations, fires, the bubonic plague, childhood mortality, waves of emigration, and deportations that went on for centuries years in Latvia, I consider myself and other Latvians alive today to be the survivors of the fittest and most fortunate. My parents’ generation certainly seems to be robust, living to a ripe, old age.

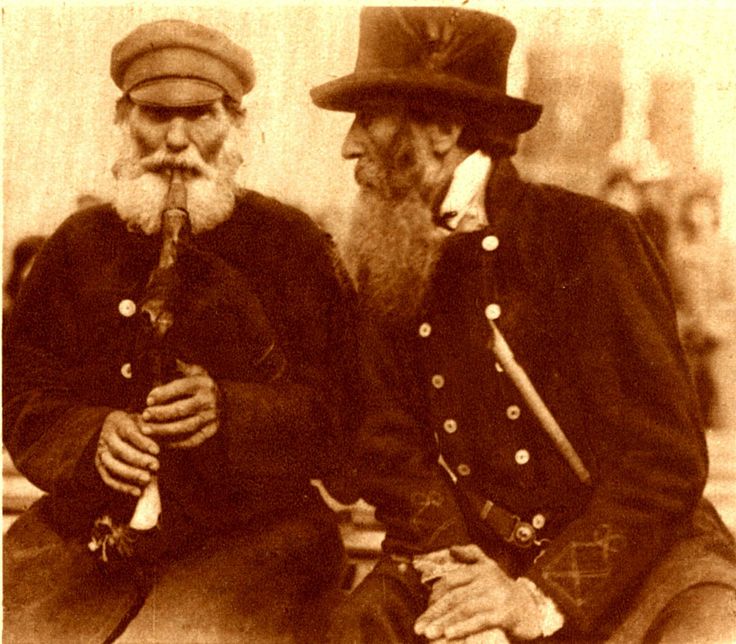

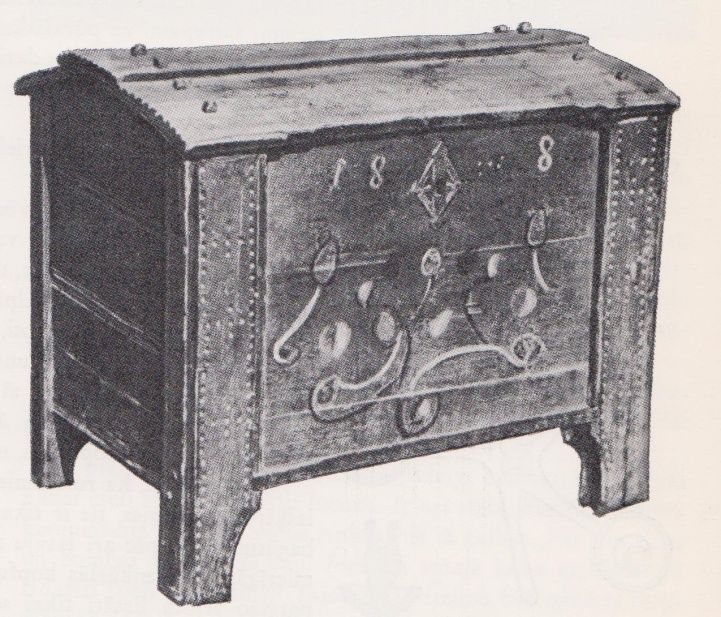

As a tiny link in a very long chain that stretches back in time, I cherish the ancient language passed down to me, as well as the rich treasure chest of Latvian culture: our delightful folk tales; our riddles rooted in everyday life; our witty, wise proverbs; our merry, foot-stomping folk dances and soothing, sometimes melancholic melodies played on the kokle (a wooden stringed instrument), the bagpipes, and the fiddle; the so-called dainas—our unique folk poetry that expresses all aspects of human existence; our traditional crafts; our ethnic jewelry with its ancient, mystical designs; our lovely folk costumes; our wooden architecture that merges so well with our northern landscape; and so on. It is a deep chest that we can be proud of, dip into for inspiration, and share with others.

Latvia, a country slightly bigger than the state of West Virginia, lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea opposite Sweden. Latvia’s neighboring countries include Estonia to the north, Russia to the east, Belarus to the southeast, and Lithuania to the south. Latvia’s geographical location as a country bordering northern Europe’s Baltic Sea, a strategic waterway and transit route, and as a stepping stone between Europe and Russia, has been both a blessing and a terrible curse. A tasty geopolitical morsel, the territory of Latvia has tempted foreign armies to invade, raid, and occupy it, leaving lasting political, cultural, linguistic, and genetic imprints. (Perhaps this is why there are so many beautiful Latvian women and good-looking men.)

The peoples that preceded Latvia’s modern nation.

Source: Wikimedia Commons https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Balts#/media/File:Baltic_Tribes_c_1200.svg

(© CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en)

Before German emissaries of the Holy Roman Empire and warrior monks began conquering the territory of ancient Latvia in the 13th century, it had been settled by numerous groups of peoples or tribes. These were: the Kurši (Curonians); Zemgaļi (Semigallians), Latgaļi (Latgalians), Sēļi (Selonians), and the Līvi (Livs or Livonians), a people linguistically related to the Finno-Ugric Estonians, Finns, and Hungarians. Like the ancient Vikings, the Kurši also took to the seas. One after the other, the local tribes ceded land to the Germans who named it Terra Mariana, the official name for medieval Livonia. The “castle hills” of our ancestors, pre-dating German arrival, can be found all over Latvia, many of them concealed by trees and bushes. The impressive stone ruins of the German invaders’ ancient fortified castles still stand today, looking more and more like rocky outcrops of the earth.They are fascinating reminders of the distant past, when peoples and faiths collided under the northern sun.

The Latvian language belongs to the family of Indo-European languages. Latvian and Lithuanian are Baltic languages said to be distantly linked to Sanskrit. Old Prussian was once part of this “family” but died out in the late 17th or early 18th century. The Old Prussians were conquered by the Teutonic Knights in the 13th century. Latvian and Lithuanian are said to be among the oldest languages in Europe.

Janīna Kursīte, a Latvian linguist and literary scholar, says: “It’s mostly true that Latvian and Lithuanian are among the oldest of Europe’s languages. Russian philologist Vladimir Toporov, who was also very familiar with Baltic culture, once said that Latvian and Lithuanian enjoyed a unique status among European languages in that they were both a ‘mother’ and a ‘daughter’ to European languages. The richness of the (Latvian) dainas and their ancient, mythical motifs are unique and archaic; you won’t find anything like the dainas among living languages and European cultures. At the same time, in terms of abstract notions of the modern world, the Latvian language is very recent, much more recent than German, English, and Russian; our modern-day Latvian was ‘created’ in the second half of the 19th century. Atis Kronvalds, Krišjānis Valdemārs, and Auseklis (Miķelis Krogzemis) were among those creating new Latvian words. We are both ancient and young; that is our blessing and our curse.”

It is interesting to note the similarities between the two remaining Baltic languages, Latvian and Lithuanian, and then the Finno-Ugric languages, Liv, Estonian, and Finnish:

English Latvian Lithuanian Liv Estonian Finnish star zvaigzne žvaigždė tēḑ täht tähti sun saule saulė pǟvaļiki païke aurinko sky debess dangus tōvaz taevas taivas river upe upė joug jõgi joki forest mežs miškas mõtsā mets metsä earth zeme žemė mõ maa maa brother brālis brolis veļ vend veli hand roka ranka kež käsi käsiThe territory around Rīga, the capital of Latvia, was originally settled by the indigenous Livs. Rīga was founded in 1201 as a political and military base for a holy war against the native pagans by Bishop Albert. The campaign was successful and established a powerful foothold for German rule for centuries to come.

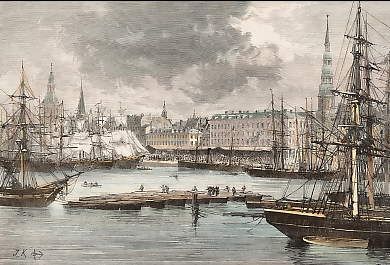

In 1282 the city of Rīga joined the Hanseatic League, an important economic alliance in northern Europe. Over the centuries Rīga was visited and settled by people of various nationalities and cultures. Artifacts from its colorful history—coins, furniture, tools, model ships, and silverware—are on display at the Museum of the History of Rīga and Navigation (1773) in the old town. The stories of the city’s past are evident in its buildings and in Old Rīga’s intriguing street names, which beg to be explained, as well as in its houses of worship. Over the centuries Rīga prospered and grew. The Daugava River served as a gateway between East and West. Other major cities in Latvia include the port cities of Ventspils and Liepāja on the Baltic Sea, Jelgava with its famous palace Rundāle, designed by Francesco Bartolomeo Rastrelli (1700–1771), architect of St. Petersburg, and Daugavpils on the Daugava River.

I am lucky to have in my possession some faded photographs of my Latvian ancestors, my senči. I look upon their faces with love and like to imagine what their day and age in Latvia was like. These photographs, as well as a Bible printed in Rīga in 1794 that was passed down to me by my maternal grandmother, I count as my most precious material possessions. My Grandmother Līvija’s and Grandfather Augusts’ slim volumes of poetry in perfectly preserved bindings (his written between 1914 and 1925—a stormy period than includes World War I, Latvia’s independence from Russia, an invasion by the Bolsheviks, and the first years of the newly independent Republic of Latvia) transcend time and space. We are linked through our mother tongue.