Полная версия

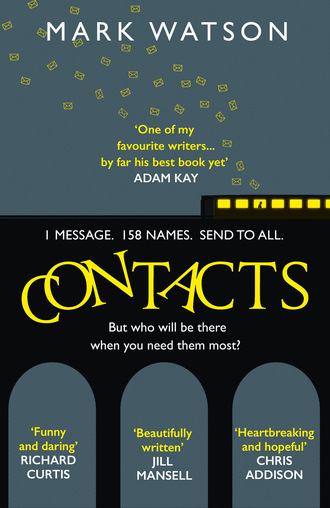

Contacts

‘It’s fine,’ she said. ‘He’ll be fine, I’m sure.’

6

LONDON, 00:30

STEFFI BERMAN

Now that the underground was running through the night at weekends, Steffi’s commute home from the restaurant was easy. Tonight had been a raucous one, a party of twenty businessmen loudly and repeatedly toasting someone who seemingly went by the nickname Billy Bollocks. One of the diners had called her ‘darling’ too many times, and for a moment Steffi had entertained a bizarre fantasy: of taking the red mullet off his plate, the whole fish, lifting it from its bed of rice, and putting it down the back of his neck. The mental image was so strong that Steffi laughed out loud, as if she’d seen it in a film rather than dreaming it up. The would-be fish victim had taken this for some sort of flirtation, as men of this kind often did when she laughed, smiled, or looked at them. But they had tipped quite heavily, drunkenly – at La Chimère they let you keep individual tips – so she was in good spirits as she walked to the tube.

If anything, in fact, the journey home almost wasn’t going to be long enough, given the entertainment Steffi had lined up. For the past couple of months her spare minutes had been mopped up ruthlessly by a phone app called ‘Sheep Wars’ – created by one of James’s successors in the game-tech business, though she had no idea her flatmate had ever worked in that field. Sheep Wars was so addictive that it was difficult to remember a time when she hadn’t played it at every opportunity. You were a wolf and your mission was to eat as many sheep as you could; if you caught enough of them, you went on to the next level. In the early rounds the game was boringly easy; the sheep were so slow and stupid that a 4-year-old could capture them. Steffi had been annoyed with Emil, the colleague who’d recommended it to her: did he think girls couldn’t play games? Or that she specifically was useless, just because of that one time she slipped on a bit of pulped avocado and smashed all the glasses?

But as the stages of the game went by, your prospective prey became faster, and more cunning. They armed themselves with weapons; they built fortresses. Last night she’d played it until 3 a.m., as usual, and to her amazement the sheep, who normally just shuffled around like real sheep, had escaped from her by jumping into a sports car and driving off laughing. This was level seventy-four and she hadn’t yet worked out how to respond to the sheep’s new cunning. Nobody online seemed to know how many levels there were; you couldn’t find anyone who claimed to have finished it. There was a theory, in fact, that the invisible creator was perpetually adding to the game; was a mad genius who had them all indefinitely enslaved.

Sometimes, on the tube, she glanced across at other passengers hunched over their own phones, and wondered if they were on Sheep Wars, too – unwittingly part of a community, even as they all played the game alone. People always looked so serious, but you never knew what was in someone’s head. Steffi remembered once sitting next to a man who was studying his screen with one of the most intense expressions of concentration she’d ever seen. When she sneaked a look over his shoulder, it turned out he was watching a GIF in which someone had made Beyoncé appear to turn into a pizza. Watching the five-second film over and over and over again, like someone newly arrived on the planet, grasping fruitlessly for context. Quite often she thought that everyone except herself was insane. The thought was half-ironic – but only half.

On the escalator up to the street, Steffi’s gaze was still fixed on the little sheep as they danced around, taunting her. She knew that before too long she would work out how to ambush the car and finish this level. And then two contradictory things would happen. She would feel a little swell of satisfaction, followed almost immediately by disappointment that this was not a real-world achievement, something that anyone else alive would care about. Steffi was not a zombie gamer, an addict, in the truest sense. She was aware that there should be more substance to life than working as a waitress in a restaurant whose online reviews were struggling to match up to its pretensions, and then spending every other moment engaged in the hunting of imaginary animals. It just wasn’t clear how to get out of this loop.

As she came out onto Pentonville Road Steffi glanced at her phone. Slightly surprisingly at this time of night, there were two new notifications. One was from Emil, the line chef, asking the staff’s WhatsApp group if anyone wanted to ‘get a drink somewhere Euston or whervr’. The proposal was backed up by emojis depicting glasses of wine, beer and champagne, as well as a dolphin; Emil was a profligate emoji user and rarely stayed on-topic. The other message was a text, from her flatmate and landlord James. In the instant before she read it, she registered that it was unusually long; she couldn’t remember him ever writing more than a few words before. Even after the bad night, the crying night, he had only messaged to say, ‘I am very sorry about all that’. She hadn’t even replied; too awkward to know how.

She read the text, read twice through the words ‘end my life’. She stopped dead outside a kebab shop, where a huge skewer of meat was rotating in the window and a couple of customers waited at the counter.

‘What the fuck,’ said Steffi out loud, to the nearly empty street, ‘what the actual fuck.’

She touched the screen to call James. It was hard even to remember the last time she’d called someone, actually called them on the phone like in the Seventies or something. With Mum it was always Skype on a Sunday. She was in constant contact with friends, but it was all instant messaging. Even with her best three or four buddies back in Holland, one of them actually phoning would mean something seismic was happening.

But now something was, or at least could be. There was a brief pause as the call tried to connect, and then the same recorded message that Michaela had heard minutes earlier. There was no option to leave a voice message and Steffi experienced a guilty twinge of relief that she wouldn’t have to.

What now, though?

Where are you? she wrote. Unlike Emil, she preferred – even in her second language – to text in proper words and sentences. Your screen looked ugly otherwise.

She stood looking at the screen in case the messaging dots popped up, in case there was an immediate reply. Within thirty seconds she knew in her heart that there wouldn’t be one. Well, she hardly even knew James, really, did she. Other people must know him. Someone else would know what to do.

But no one else was heading home to James. There was no escaping that. If he had done something to himself in the flat, Steffi was going to be the one to find him. The knowledge flipped her guts. Although she was only seven minutes away from the flat, it seemed impossible all of a sudden to imagine going in there, finding …

That wasn’t a thing that just happened, though, she told herself. Your flatmate did not spring something like that on you. Even if you kept to your own space like the two of them did, you couldn’t be living with a person and not know that they were on the verge of something so drastic, surely. Steffi thought about the suicides she’d seen in crime dramas, which she often bulk-watched when the insomnia was getting her down and her eyes wouldn’t focus on the sheep any more. Gun in the mouth, rope hanging from a beam. A politician blackmailed, a lover rejected. These characters had suffered some disaster, they’d lost their minds; there was nowhere else to go. That wasn’t James. Yes, he’d perhaps been down recently, but he was hardly a guy to ram a gun in his mouth. She’d seen him decide against going to the cinema because the weather app said there was a 60 per cent chance of rain.

A little rain was falling now, too; a drop landed squarely on the screen, distorting the green and grey boxes of text. She shivered. It wasn’t winter any more, but March in London didn’t exactly seem to be spring, either. Steffi swallowed hard a couple of times. I could do with a drink, she thought. A drink would be nice.

As she rounded the corner onto their street, the noise of the main road fell away as quickly as ever, and so did the big-city feeling. It would have been hard to guess now that it was a Friday night, or that they were so near a major transport hub. Some windows offered glimpses of warmth: a dinner party that had extended its run past midnight, a couple in front of a late movie. Steffi told herself that if James had done anything, there would be some activity, some visual sign of it. Police would already be here. Concerned neighbours would be hammering on the door, like they did on Netflix. But no, not necessarily. He’d sent the text under an hour ago. She could easily be the first actual witness.

She wet her lips with her tongue, went down the four stone steps, took a breath and put the key in the lock.

The place was as neat as ever, James’s hat and coat hanging where they always were, next to the denim jacket that she’d decided was too much like old-school Madonna, and which she hadn’t bothered to pick up from the floor because she was worried about being late for work. That was a good sign; it must be. You didn’t worry about tidying the hall the same day you went and did yourself in. But the odd calm of his message came into her head again. I know what I’m doing.

‘James?’ she called. ‘James? Hello?’

She was almost sure from the dead way her words landed that nobody was here. It didn’t diminish her sense, though, that she was in a TV show, one where a minor-key soundtrack was building subtly under her footsteps. She never liked coming back alone, really, not since the burglary at her old place in Clapham. One of the girls at La Chimère had been assaulted on her own doorstep the other week, violent crime was up in London; although not normally a jumpy person, Steffi had bought a ‘panic alarm’ and a small knife online in the past month. Knowing that James was almost always in – that he was almost certain to be in his room when she got back from work – had always been a little bonus about living here, although this was the first time she’d ever consciously had that thought.

His bedroom door was wide open, giving an unaccustomed glimpse of the bare floor, a neat little pile of books; so was the bathroom door. All clear in the kitchen. Steffi approached her own room with a trepidation she had never felt before. Christ, imagine if he’d done something in there. That really would be fucked-up. She’d have to move, again.

A lean on the handle, and the door was open a crack; she pushed it a little more, then all the way. Everything was where she’d left it. The clothes scattered across the floor like wreckage from an accident, the dormant laptop at the end of the bed. Wherever James was, he was not here.

On the kitchen table was a note.

Hi Steffi. Really sorry for any fuss. I’ve scheduled an email which you’ll get in the morning, re. the flat. You can stay, of course! It shouldn’t be too complicated. Good luck. James.

The fridge was still full of his stuff: the blocky cheeses he seemed to like; the full-cream milk she couldn’t stomach. A big green box of eggs. Again, it didn’t make sense. You didn’t buy eggs and then two days later overdose or something. ‘It shouldn’t be too complicated.’ Was he taking the piss? What was this?

She sloshed some gin into a wine glass, topped it up with partly flat tonic water. The phone lit up with a message and she jumped. No. It was just Emil again. He’d been drinking on his own since he sent the last one, he said, with six crying-face emojis, three winking ones, and a watermelon. He couldn’t believe nobody else was out, he added.

In a series of purposeful swigs, Steffi saw off the drink. She always drank quickly, not out of greed, she thought, but because her brain tended to see it – like everything – as a task she had to complete. She pushed the glass aside and messaged Emil.

You want to do something with me?

She saw him begin typing at once. She and Emil didn’t know each other especially well. His English was poor, nowhere near her level. He was small, with dark eyes and a fluent, almost mesmerizing kitchen technique. Sometimes as she came in with orders, she would watch him for a second, drizzling rings of pesto like green blood onto the ice-white plate, turning a mountain of herbs to confetti in seconds. It was very attractive watching someone do something with such ease. If you didn’t look at his face too hard. Anyway, it was only ever a moment; that was all you got, in the kitchen, before someone screamed at you.

Do what? Emil replied. He followed up with a fusillade of emojis which included a face deep in thought, a couple of drinks, a detective with a magnifying glass, a dancer, a guitar and the flag of Iceland.

Can you meet me Kings X station? Got some shit going on.

Emil accepted the cryptic invite with a line of girls in tutus. Steffi went to the bathroom and looked in the mirror. Her pupils were dilated; a bit of colour had risen in her normally pale face. She blinked and rubbed her eyes. She was surprised to have invited Emil into this; she was surprised to find herself in any sort of drama. But here it was, and she could hardly just pretend it wasn’t happening – that she hadn’t read the message. She’d get those jeans off the floor, go back out. And see where this took her.

She was worried for James, however passive their relationship. The guy couldn’t be well. He needed help. She was worried for herself, too, because never mind what he said: if he did turn out to be dead, her life was surely going to get all kinds of complicated. She felt the prickly edge of guilt that he had cried in front of her not long ago, and she had taken it as a mere bad night rather than a sign of something more significant.

But there was something else, as she looked in the mirror, some other emotion stirred up by the bizarre turn this night had taken in the past half-hour. Here, at last, was something that was not a game. Steffi felt bad admitting it to herself, but the feeling was a little like excitement.

7

LONDON–EDINBURGH TRAIN, 00:49

Branches, like gnarled old trolls’ nails, scratched at the train on its way past; small handfuls of rain were thrown at the windows. The train didn’t sound like it was enjoying it. It was surprising, James thought, how noisy sleeper trains were, given that you were meant to sleep on them.

He’d always loved buses, planes, trains. A train barrelling past, a plane swooping as close as a bird as he negotiated the M25 interchange with some important client: getting right over their heads, so they could see the underside of the fuselage, the little marks in the metal. As children, James and Sally had a whole series of books in which animals bustled around a town, putting out fires or teaching kindergarten classes of smaller animals. The junior-level computer games he wrote as a nerdy child were always about things like being an air-traffic controller (‘press A to reroute the flight; B to never compromise with terrorists’). Even when he first met Karl, he was working in idle moments on a game called ‘National Rail’, where you had to get around the country as fast as possible using real train routes – something Karl had found hilarious. ‘You’re making a game about something that isn’t even fun in real life? What’s next, Jamie, a game about getting your central heating fixed?’

Sure enough, it had never seen the light of day, just like James’s similar pet project ‘Bus Magnate’. But he never lost enthusiasm for the sight of a train zipping past, a plane soaring at its almost impossible angle into the sky. These sights meant people had places to go, places that might be better than here. Transport in action still gave him something of the warmth of those old Richard Scarry books, of their agreeable sense that there was a plan. Or had, at least, until recently. Until the sacking. Until he began to lose faith in the idea of plans altogether.

And yet he had been on a sleeper train only once before: with Karl and Michaela, on a trans-European holiday jaunt which was only a bit more than five years ago but might as well be fifty years, as the memory, along with all his others, receded into the darkness down the track. Even though James and his dad had gone to Edinburgh every year by tradition – right up until Mr Chiltern’s death – they’d never done an overnighter. Largely this was because of an intuition on James’s part that sleeper trains were something of a thin man’s game. That had been backed up by his experience tonight so far. The bed he was lying on was barely wide enough for a healthy-sized child. The word ‘cabin’ on the website had possessed a certain grandeur, evoking the QE2, that sort of thing; the reality was a room which, to a man of James’s dimensions, felt a little like a cell. His plan had been to put away two or three beers quickly and then fall asleep until the moment came, but it was already clear that might be more difficult than he’d imagined.

Still, the beer was helping; as the first can signed off, he could already feel its contents nudging the dimmer switch of his mood. It was quite a while since he’d really enjoyed a drink. When they got on the train at Euston – each passenger checked in by a vigorous, curly-haired Welsh woman who said things like, ‘We’ll be in at seven, but you can occupy until seven thirty’, there had been a large number of benign beer drinkers, in red scarves and rosettes, on the way to some sporting event that James wouldn’t know about at the best of times, and would certainly now miss as he would be dead. He’d eyed them for a second, listened to their oiled, jolly bantering, with what was almost regret. Might things have been different if he’d been more of a drinker – if he was a bit better at relaxing? For some people happiness, or at least a sort of hazy, zoned-out contentment, seemed that easy.

But, as he reminded himself now, he had been that person once. He’d had a gang, even if it was a smallish one, and largely drawn from friends Karl introduced him to. In his years working for the tech start-up, they used to go to the pub almost every night. Karl – because he was working on a web encyclopaedia, as part of the project – would entertain the group with his knowledge of various historical figures’ lives, and James – because he paid more attention to detail – would quietly correct that knowledge.

‘This woman, can’t remember the name; they reckon she was the one who came up with DNA, but being a bird, they took the Nobel Prize off her …’

‘Rosalind Franklin. Actually, she never got the prize.’

‘What’s his name, Neil Armstrong, the geezer that walked on the moon: do you know, he said the “one small step for man” bit slightly wrong; he messed it up because he’d got the yips being up there – fair play, really – and also did you know he once punched a bloke who claimed that they never went to the moon at all?’

‘That last bit was Buzz Aldrin, I think.’

The start-up, where Karl and James worked in their mid-twenties, had been creating a platform called OnLife: a portmanteau of ‘online’ and ‘life’, which Karl feared was a ‘dogshit name for something that’s supposed to be cool’. Karl had tried to point this out once to Jacob, the handsome dimpled blond whose company it was – but unfortunately, he had used exactly those words, and had been drunk, and Jacob was from some nebulous but severe American background which meant he disliked both swearing and drinking. Even if the name was always a bit tin-eared, though, the actual project had at one time seemed very exciting. It was based on the notion that the internet’s best things would not remain free for ever. Email couldn’t always be free; nor could massive resources like Wikipedia, nor connection tools like Facebook. One day, in Jacob’s view, there would be a single hybrid of all these entities – a single place you went to do, as he put it, ‘everything you want to do with a computer, and some stuff you don’t even know you want’. When this megalith came along, people would subscribe to it in their masses.

So James and Karl’s job had been to write code for a sort of web encyclopaedia which could also use algorithms to predict the sort of facts you probably wanted to search for. Other people in their office and flat-share were responsible for building other parts of this internet planet. A Taiwanese man called Yan – who never spoke a word of English to them – was creating a messaging service. Katarina, the only woman in the set-up, was coding a personal organizer which would allow your computer’s diary to sync with your mobile. There were twelve people employed by the company, and all of them were working on good ideas, ideas that would become very popular. But the overall conceit – that people would one day pay for what was currently free – proved a disastrous one. The consumer testing went badly. And even as Facebook’s share value was darting upwards like a spider climbing a wall, Jacob’s funders, whichever rich Californians were bankrolling his experiment, pulled out overnight. James was grumbling to himself over a line of code, something he’d wrestled with for three hours already, when Karl shuffled into the office, late as usual. He began a good-natured reproach – Karl averaged around half as much time actually working as James did – but Karl cut him off with an unusual edge to the humour in his tone.

‘I wouldn’t be sweating over that too much, Jamie, my man. I don’t think Jacob’s going to show up for the meeting.’

‘And what makes you say that?’

‘It’s a hunch,’ said Karl, ‘based on a couple of clues in the voicemail he’s just left me, which said he was about to get on a plane, our company didn’t exist any more as of this morning, he’d already got a job lined up for the Federal Reserve back home, and he was sorry but he didn’t think we’d ever meet again.’

All but James and Karl moved out of the flat after that, and by now James’s core friendship group was scattering too, on the various winds that always blew groups apart in their late twenties: marriages and children, New Zealand holidays that became permanent stays, nervous breakdowns triggering dramatic career changes, and so on. But even well into his thirties, now driving cars for a private hire firm and helping people fix their computers on the side, James would have said he was broadly happy, most of the time. There were still the nights out with Karl, when Karl came back from whatever monstrous job he was currently trying out. There were the Edinburgh trips; there were dates and little tentative romances. By now there were certain mental ulcers, too, rubbing away at him, flaring up. He was aware that he was a little heavier than he’d like, that a decade and a half of sitting down had left its mark on his body; he worried that it was getting late to meet the right person, that it was never going to happen simply by having pleasant chats with people in the back of his car. Once Michaela had entered his life, these problems, along with all other remaining ones, disappeared. But in time Michaela herself had then disappeared.

Despite being dumped by her, and thrown aside by Karl, James had never imagined himself as a person for whom unhappiness could be this thick and choking; a person who would go home at night and simply not know what to do with himself. He understood there would be crises, even in an unremarkable life, but it turned out there was something worse than the adrenalin of a crisis: the endless flat grey afternoon of depression. The terrible night he had cried in front of Steffi, three months ago, had been the first time he’d really understood how hollow he felt, and had been feeling, and would keep feeling. Even after googling ‘depression’ – an act which released a flood tide of pop-ups that said things like, It’s OK not to be OK and Take a mate for a pint, he would have thought it impossible that he would ever be desperate enough to call the Samaritans. Until the morning, midway through January, when he’d gone ahead and done it.