Полная версия

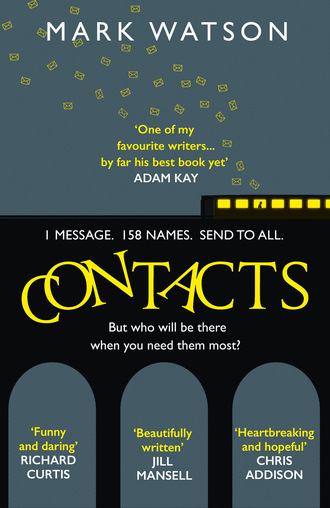

Contacts

CONTACTS

Mark Watson

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2020

Copyright © Mark Watson 2020

Jacket Photographs: Cover illustration © Benjamin Harte/Arcangel Images

Cover design by Claire Ward and Lucy Bennett © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2020

Mark Watson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008346966

Ebook Edition © ISBN: 9780008346980

Version: 2020-09-15

Dedication

For Coop,

who changed my story for good.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Part One: The Text

Chapter 1: 8 March 2019: 23:55

Chapter 2: 9 March 2019: London–Edinburgh Train, 00:02

Chapter 3: 9 March 2019: London–Edinburgh Train, 00:06

Chapter 4: Melbourne, 11:25

Chapter 5: Berlin, 01:27

Chapter 6: London, 00:30

Chapter 7: London–Edinburgh Train, 00:49

Chapter 8: Bristol, 01:01

Chapter 9: M1 Near Luton, 01:23

Chapter 10: Everywhere, 01:45

Part Two: The Contacts

Chapter 11: London–Edinburgh Train, 02:05

Chapter 12: Melbourne, 13:05

Chapter 13: London, 02:32

Chapter 14: Berlin, 03:32 M1 Near Leicester, 02:32

Chapter 15: London, 02:48

Chapter 16: London–Edinburgh Train, 02:52

Part Three: The Mission

Chapter 17: Everywhere, 03:15

Chapter 18: Melbourne, 14:25

Chapter 19: Bristol, 03:38

Chapter 20: London–Edinburgh Train, 03:50

Chapter 21: Berlin, 05:02

Chapter 22: A1(M) Sefton Park Services, 04:34

Chapter 23: London–Edinburgh Train, 04:57

Chapter 24: London, 05:35

Chapter 25: Melbourne, 16:35

Chapter 26: Bristol, 05:47

Chapter 27: Newcastle, 06:02

Chapter 28: London–Edinburgh Train, 06:30 Berlin, 07:30

Chapter 29: Melbourne, 17:55

Chapter 30: London, 07:04

Chapter 31: A1 Near Dunbar, 07:15

Chapter 32: Everywhere, 07:20

Chapter 33: Edinburgh Waverley Station, 07:22 Berlin, 08:22 Melbourne, 18:22

Chapter 34: Edinburgh, 08:01

Epilogue: Edinburgh, 20:45

Author Note

Keep Reading …

About the Author

Also by Mark Watson

About the Publisher

1

8 MARCH 2019

23:55

I’ve decided to end my life. I know this will come as a shock to some of you and I’m sorry if it upsets anyone. Sorry, also, if a text message is a strange way to find out. I am not sending this for you to try to change my mind; I know what I’m doing, and I’m fine. I just wanted the chance to say goodbye and to thank you for the things we have shared. James x

2

9 MARCH 2019

LONDON–EDINBURGH TRAIN, 00:02

Texting 158 people at once was a strange feeling – stranger than James had expected. The task of drafting the message hadn’t been difficult at all. In fact, it had been cathartic to write it. It was as if he didn’t fully believe he was capable of taking this dramatic action until he’d committed it to the screen. It was the difference between making a mental vow and saying it out loud. And now, telling every single one of his contacts: that was the final step. You didn’t tell 158 people you were doing something and then duck out of it. This was sealing the deal.

Most people would probably have a more tech-efficient way of spreading the news. WhatsApp, perhaps.

Even as recently as five years ago, well after he’d left the tech world, James would still have found it difficult to imagine not having a Facebook account. But then, he would also have found it difficult to imagine not having a girlfriend, or best mate, a healthy relationship with his sister, a purpose. He’d come off Facebook, and everything else like that, as soon as Michaela left.

This was his final act of sharing, you could say. It was a bit of a clumsy way to do it, he reflected, reading the message which was about to be dispatched to his entire phone book one more time. The ‘James x’ looked ridiculous to James’s own eyes. He never normally signed off with an ‘x’. He’d been left behind by the age of over-familiarity between virtual strangers. Only recently, before he got sacked, a passenger he was picking up – a total stranger – had sent him a GIF of a goat eating a chocolate bar whole, with the caption ‘SWEEEEET!’ Again, at one time James would have found that funny, responded with something similar. But when you were lonely, fake displays of friendship made things feel lonelier still. And fake was all he had, now. A brief smile exchanged at the table with his flatmate, a friendly nod on the way into work. They weren’t enough. You couldn’t be almost forty and be living off these crumbs of affection. And now he wasn’t going to, any more.

They can have the ‘x’, he muttered to himself, with a private little smile. He felt the lightest he’d been for a long time: light both in the head and in this flabby body he’d come to despise. Neither brain nor body mattered so much, now that he was almost done with them. They can have the ‘x’ just this once.

He could feel his heart skip against his ribs as his finger slid onto the screen. This was it. There was no recalling this message; it would be out there immediately. Everyone knew how unforgiving it was, the instant-contact world they all lived in. Michaela had once written the sentence ‘my tits feel like they’ve been through a mangle’ and sent it by mistake to a colleague. He could remember how she described the realization, the dizzying rush of stomach into mouth. James almost smiled again at the memory of his ex, but this time the smile died, and he took a deep breath and pressed send.

The moment itself was curiously undramatic. It wasn’t even one single ‘moment’, as James had imagined it when he’d looked ahead to this night – which he had naturally done a lot. Some of the numbers in the phone book were out of date, some phones were switched off this late; exclamation marks immediately started appearing on the screen. It was not immediately obvious who had got the message and who would remain ignorant of his plan until he was already gone. But he wasn’t about to find out. The phone was going onto flight mode and would stay that way.

Of course, nobody could find him here – he had planned it well. Nobody could physically stop him; that had been a given as soon as they pulled out of the station. All the same, he didn’t want to be bothered, over the next few hours, by people’s responses. This wasn’t a proposal: it was a done deal. Flight mode was a good compromise. He didn’t want it off altogether, because the phone was his only timepiece, for a start. It would be reassuring to keep an eye on the time. To know how close he was to half past seven in the morning, when it was going to happen. The phone would be by his side, but surrounded by a force-field. Nobody could touch him, now.

A little aeroplane icon popped up at the top of the screen to confirm that it was no longer possible for any of James’s contacts to speak to him. This time, the moment was as rewarding as it should be, did feel as significant as it should. Admittedly, it wasn’t quite the end of his interaction with the rest of humanity. It was possible he’d have to speak a few words here and there before 7.30 a.m. But no real conversations. Those were done with. No more opportunities to mess up, to disappoint others, or himself. It was done.

James rummaged in his plastic bag, bringing it up onto the narrow bed with him. For his final meal on this mobile Death Row he had brought two pork pies, a six-pack of beers and a packet of plain chocolate digestives. What a spread, he could hear his sister Sally saying, in the mock Famous Five voices they used to adopt in their early twenties: the youthful person’s mockery of the only-just-past. He removed the biscuits from the bag. Tearing off the yellow strip to open the packet, stuffing the first biscuit into his mouth, provoked the usual rush of guilt and shame. It was a conscious effort to remind himself that those feelings were obsolete now, that he was free, he could eat whatever he wanted. Do whatever he wanted, for the whole of this ghostly night that was left to him.

It had surprised him a little, how slow the adjustment was. The way that, even though he had made his decision weeks ago, the body and mind kept on with their business. That was what life was like, he supposed. An amazing amount of it was lived almost automatically, and could be for many years, unless one found the courage to change it – or do what he was doing now, escape it.

James’s actions this afternoon wouldn’t have looked to an outsider like those of a man about to kill himself. He’d approached it like any other day off work. He’d cleared up the crumbs of cheese left from his mid-afternoon snack, polished the kitchen surfaces, hoovered, straightened the jumble of shoes by the front door and hung up his flatmate’s jacket, which was lying in the hall. Before leaving the flat for the last time, he had gone into the bathroom and made sure the shower dial was turned tight to the top, because the shower had a habit of spewing water out of its pipes at unpredictable times – noisily and sometimes for several minutes, as if it had an invisible user standing under it. Admittedly, these actions hadn’t been for James’s own benefit – it made no sense to talk about ‘benefit’ when he wasn’t going to be alive this time tomorrow. But there was his flatmate, Steffi, to consider.

‘Flatmate’ was a generous way of describing their relationship, as was the case with all the people who had moved in and out in the three years since Michaela left. The two of them weren’t close; they’d barely had a detailed exchange until that recent night, still mortifying to think about, when she’d seen him crying. James generally came home from work at the station at around seven, and usually Steffi was already out, waiting tables, by then. Their main transactions revolved around the Amazon packages which Steffi was always receiving early in the morning, and which James collected for her because he knew she would still be asleep. Sometimes he thought he had more conversations with the delivery man – who always said the same thing, ‘just a signature here please, chief’ – than with Steffi herself. But he certainly didn’t want her to think badly of him now he was gone. That was why, as well as making sure the flat was nice, he had left her an email with detailed instructions: how to contact Michaela, who was still the landlady, and what to say to anyone who got in touch.

Steffi (there was no denying it) would be inconvenienced a little by what he was about to do. It was bad news logistically if the other person in your flat killed himself. But she was a capable, practical woman – he knew that much about her. She’d be fine.

Everybody would be fine. In a few cases their lives would be better, in fact, as a result of this. If James hadn’t believed that, he would not have made this decision. He helped himself to a second biscuit, turning it upside down as usual to enjoy the hit of the chocolate coating a couple of seconds more quickly.

‘God, that’s nice,’ he found himself muttering, and grinned at the oddness of the situation. It was so freeing to have made this decision. I feel alive, he thought, somewhat ironically.

A third biscuit. Eighty-six more illegal calories. He could still remember the figure from the weight-loss app that used to patrol his and Michaela’s diets like a prison guard. Eighty-six calories, astoundingly, in a single biscuit. But it wasn’t illegal any more. There could be eight million calories in a biscuit, he thought, and it wouldn’t matter. Nothing was a problem any more. He visualized for a second an insanely large biscuit, himself eating his way through it, and almost smiled again as he realized where the thought came from: Sally had once helped him get off to sleep with a made-up story in which he was trapped inside a giant peach, like his Roald Dahl namesake. But the thought of her gave him a pang of sorrow – they would never be young and full of in-jokes and cynicism again, never be brother and sister again – and he forced it away. There was no room for that stuff now.

He yanked a cord to pull the blind, revealing a grubby little square of window. It was midnight: indistinct shapes went by in the darkness. James thought about all the texts, the messages-in-bottles, shuttling invisibly through the night sky. Some of the recipients would be asleep by now, wouldn’t see the news for hours yet, perhaps not until he’d done it. Others would half-read the message through sleep, or glance at it but fail to absorb it.

But a few people would already have read it, and some perhaps were trying to contact him right now, hammering in vain on the screen-door he had pulled shut across his phone. James wasn’t so detached from his life that he couldn’t see that. If Michaela and Karl saw the message, they would certainly try to get in touch. Their brains would shine a beam on everything good about James, everything (as his message said) they had shared. The mad escapades of years gone by, like the time they raced around all the Monopoly squares in London; or that night they spent grovelling around on hands and knees to capture a frog that had found its way into the flat during a storm. Michaela would remember how he always brought her a morning coffee although – in his own words – he felt like an absolute dingbat trying to say ‘matcha latte’ to the youthful, band-T-shirt-wearing baristas who probably discussed him after he’d gone. Karl would remember watching middle-of-the-night foreign films after a shift, joining the action an hour late, debating who the killer might be only to discover at the end that it hadn’t been a murder mystery in the first place. Both of them would remember the fun things, the filtered memories, and the hysteria of the moment would make them forget that they were the ones who’d helped to cast him into this grim place.

Even people with less invested in James, which was almost everyone else amongst his contacts, would be concerned. Humans were naturally programmed to think that way, for their own protection. They’d say that he ‘wasn’t in his right mind’, that he was a ‘danger to himself’. They would convince themselves that this was a tragedy which needed averting, from which they could emerge as a hero. They would be reacting, in other words, not to James’s actual situation, but to the drama. So their reactions would be fished out of the first-aid kit everyone had for dramas. And they would be wrong. It was a long time since he’d felt so decidedly in his right mind: so calm and in control. As for being a danger to himself – no, it was the opposite. He’d been a danger to himself when he was alive, when he was still trying to make out that he could cope with what that required. He was safe now.

He put the phone down on the sad little ledge that passed for a bedside table here. It was odd how small the phone looked, all of a sudden – a trick of the mind, perhaps, now that it had been stripped of its powers. It was an object again, inert like a brick, rather than an ever-watchful second brain. It might as well be a toy.

3

9 MARCH 2019

LONDON–EDINBURGH TRAIN, 00:06

James had a momentary flashback to his first encounter with an iPhone. It was 2007 and he’d just moved in with Karl and two other coders. Karl had brought the phone home from an Apple event which they’d all been invited to because, at that time, their start-up had been regarded as a pacesetter.

‘Look at it, man,’ Karl had said, holding it out like a bar of gold on the kitchen table. ‘You just touch the screen, like this. Not you.’ He playfully swatted James’s hand away. ‘Compulsory hand-wash before you even go near it, fam. This thing cost an arm and a leg. Look at it. You flick through – beautiful, isn’t it. Your conversations, it shows you like this. You’ve got all your apps, you’ve got all your music on it, like an iPod. It’s like a computer but the size of a phone. These things are the future, man, for sure. Ten years’ time, they’ll own us.’

‘How did you …’ James almost stepped back from the question, feeling it was the sort of thing his mother would ask – much too square for conversation with Karl. Karl wasn’t much like the programmers James had met while getting his degree, or in the past couple of years touring as a freelancer around the IT departments of companies which had only just upgraded their equipment from abacuses. Karl had pecs like Argos catalogues, his black skin was covered in tattoos of objects that James thought you could probably do violence with, he was keen on romantic adventures which always backfired. On their first week in the flat together, a woman had turned up in their kitchen shouting that Karl would be ‘judged by history’, and yet half an hour later they’d been having sex so loudly that James had to try to drown it out with a documentary about someone he didn’t recognize touring India’s railways. Yes, Karl was a lot cooler than James. Still, sometimes the cool found it useful to have the less cool around. James considered himself difficult to beat when it came to knowing the rules of board games and how long to put things in a microwave for.

‘How did I afford it?’ Karl raised his eyebrows. ‘Is that what you were going to ask?’

‘Sorry if it’s a rude question.’

‘It’s a fair question, fam. Because it actually brings us on to something I wanted to ask you about. This is a bit difficult. I got the phone by making use of my credit card, right. But that does bring me close to the credit limit, which I didn’t realize, so I’m going to have to ask you a favour.’

James smiled. It was promising, having this man who hardly knew him, ask a favour. James felt he was at his best when helping out, being a steady pair of hands, as his school report described him – something which Sally criticized as faint praise (‘you’re better than that’) but which James himself was pleased with. ‘How close to the credit limit, and is the favour helping you with the rent this month?’

‘Close to the point of being, arguably, over it,’ said Karl, ‘and yes, although I feel like a dick, I’m going to have to ask you if you could pay a bit of it on my behalf.’

‘How big a bit?’

‘A very big bit,’ Karl conceded, ‘by which I mean, all of it.’ James laughed out loud, and Karl brandished the phone by way of explanation. ‘Again, yes, I probably shouldn’t have bought it, but: look at this, right. This app is a fishpond and you can send fish to people who have the same phone. We need to copy this idea. This is what everyone is going to want.’

‘Imaginary fish?’

‘Connection. Networks. The world is one massive team, fam. We don’t know the half of it yet.’

The James of then nodded, agreeing as he always did, thinking sheepishly that although this was almost certainly true, he himself didn’t need much of a network beyond what he already had: his family, a couple of friends, and now Karl himself. The James of now, ten years on, winced at the crack of the ring-pull, which sounded rather dramatic in this enclosed space: as if he was trying to make some sort of point by opening the can. When in actual fact he wasn’t trying to express anything at all. He, ‘James’, was nothing any more – that was the idea. He was passive here, with the creaking and moaning of the train’s body around him. Everything could just carry on without him. This wasn’t an act of aggression, just withdrawal.

He swigged from the can, feeling the metallic taste crawl across the back of his tongue. The moment of sensory engagement brought James back into being himself, and he looked at the gagged phone and thought how strange it was that you could go, so quickly, from that to this. From being protected, feeling that you had a place in the world, to this: sitting on a sleeper train, with a bag of beers, knowing you were going to commit suicide shortly after the sun came up.

‘Suicide’. He wrinkled his nose. It was a very attention-seeking word. And notion. James remembered the way he’d once had to stop the car because the radio reported that a friend of James’s celebrity passenger, Hamish, had ‘taken his own life’ in Los Angeles. Hamish had sat, thumping the window over and over again, while James reached back and offered him a hand, an intimacy he would never normally risk with a customer. ‘Suicide’ was for people like that: depressed millionaires, or rock stars. It wasn’t for people like James, people who went to work every day, feeling progressively more invisible, feeling fat and hot and useless. Nobody was going to sob in the back seat when they heard about James. No, ‘suicide’ was an overblown word for what this was. ‘Taking his own life’, likewise. Taking it from whom? You couldn’t steal from your own bank account, could you?

It was more like resigning, as you would from any job which you had proved unequal to. I resign from life, muttered James to himself, with a half-smile. It was almost fun, this. The sensation of a load released. And it didn’t really matter, in the end, what name you gave to what he was about to do. After it, there would just be a full stop, and relief.

4

MELBOURNE, 11:25

SALLY CHILTERN

Twenty minutes until the interview, Sally’s ever-eager phone reminded her. Twenty minutes till the Age journalist showed up. That was fine. She’d be at the office in ten. After that, the phone could say what the hell it liked, because it wouldn’t be with Sal any more. She would have given it to her personal assistant, Meghan, who would deal with anything that came up – any calls, emails – while Sal was busy. As usual, Sal’s husband Dec had all her appointments in his diary, and he knew not to send dirty messages outside what they called the Filth Windows, or FWs. He was much more into rude texting than Sal was, but she did miss it a little bit when the phone wasn’t with her. In all other ways, though, not having it for a couple of hours was a blessing. It was great having Meghan to shear through the weeds that grew ceaselessly in her inbox. Invitations to speak unpaid, for Christ’s sake, like she was still 21. ‘There’s no budget, but the girls would be so thrilled to have you and we’ll feed you well!’ Emails from struggling restaurants, her name dumped in the subject line in a hollow attempt at chumminess. ‘Sal, we haven’t seen you in a while!’ You had to turn down the background buzz, sometimes. Background buzz. I like that. I could use that in something.