Полная версия

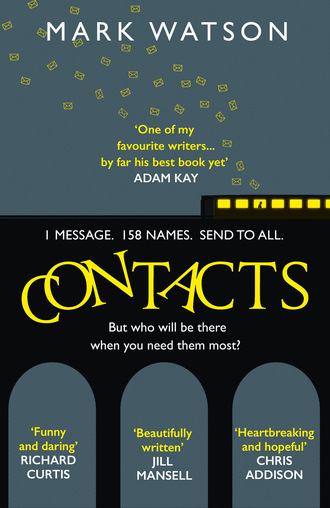

Contacts

It was definitely a thing you heard more and more about, the effect carrying a phone everywhere had upon humans. She’d heard on a podcast that scientists were already recording a change, for the worse, in global sleep patterns – even among people who switched their phones off for the night. Just the presence of the devices created a sort of subconscious twitchiness, an unease. It was a product of the slavishness which the world had wandered into; of the mental pattern established by checking a single device hundreds of times in a day. Asleep or awake, the brain reached insatiably for the phone.

Still, it was amazing what they could do, you had to admit it. Right now, Sal could see from the screen that it was twenty-five degrees – beautiful early autumn weather, although she had never got used to thinking of the seasons the wrong way around. She could see, if she opened the relevant apps, the stock markets, a range of sports scores. Neither finance nor sport was a big interest of hers, but she found it useful to have a bluffer’s knowledge of both, as she did with a huge range of subjects. If she flipped on to WhatsApp she could follow the excited chatter of three of her mates who were organizing a trip down to Lorne for Easter. The chief organizer was unemployed, so the build-up to this three-day holiday had become her major undertaking in life: she’d set up the chat group as early as Christmas and it had now produced more than a thousand messages in total. Sal rolled her eyes indulgently at the latest dispatch. Still so pumped for April, girls! What was Bridget going to do when it was all over? She’d jump in the river.

You didn’t need a phone, of course, to see that it was a glorious day. The sky, over the dashing art-deco façades of Bourke and Collins streets, was a confident blue, Australian blue. Weekend shoppers were out; in rooftop bars, weekend drinking had begun already. Some people would find it weird going into the office, doing promo, building up to a big speech, on a Saturday. Melbourne, even more than other cities, reminded you at every turn it was fun time: crowds flocking to the stadium, rowing boats slicing their way upriver. But Sal didn’t mind it at all.

She’d always liked the feeling, in fact, of working when others weren’t. As a high-flying teenager she used to help James off to sleep by making up an adventure – do you fight the monster or hide, the same as his computer games but without the computer – and then, when he was snoring, return to her desk, her midnight essay. Being active while others slept: it had felt like a superpower of some kind. Even now, she hadn’t entirely lost the buzz that came from being many hours ahead of Britain, something she was able to discuss on a weekly basis because Mum never seemed to tire of it. Now, what time is it there? Breakfast? Goodness!

Near the top of Bourke, Sal paused, as she occasionally did, to enjoy the sight of all the bustle. Melbourne often reminded her of those Richard Scarry books they’d had as kids. Of course, it wasn’t always that smooth. On almost this exact spot just before Christmas, a tram driver had had a bust-up with his wife, let his mind wander, hit someone who was checking the cricket score on her phone. She survived, but the streets around Sal’s workplace briefly went crazy. Police tape everywhere, one of the city’s central arteries clogged up, two hundred people made late for work or doctor’s appointments or dates. In one of her columns, Sally had used it as a salutary example. There was nothing an individual could do about the potential for mayhem that existed when humans tried to carry out their plans at the same time as one another. So you had to outsmart it, leave more time, plan well. Expect things to go wrong.

It was lucky she’d survived, or Sal would probably have felt bad using her as an anecdote.

Already in her mind’s eye, Sal could see the peninsula which she and Dec were driving down to next weekend. A spa, a wine tasting. Dec would undoubtedly overdo it at the winery and be all over her before they even got back to the room, which had a hot tub and a ‘romantic terrace’. He was a bit route-one sometimes, Dec, but at least he still fancied her, which was more than was true of some people’s husbands. One of the girls in the WhatsApp group was the only person in Australia not to know that her man was gay and regularly getting spanked by a sommelier. Sal was planning an intervention next week. Everyone agreed she was the one to do it. The trouble with being a business expert was that people seemed to think you could sort out pretty much any other type of business, too. Just like the way that, because she’d written a bestseller on time management, people thought it was hilarious if she was ten seconds late anywhere.

‘See the footy last night?’ asked Arnie, the concierge, rising very slowly to usher her to the lift. Although Sal had been working in this building for three years, a recent security overhaul meant that you now had to be bleeped into the lifts with an ID card which he alone, in the building and perhaps the universe, possessed. She had a suspicion that the ‘overhaul’ had been effected purely to give Arnie some duties to carry out, but if so, he hadn’t exactly risen to them. As always, he shuffled across the hall as if it didn’t really matter whether Sal got upstairs today or tomorrow.

‘Bombers were a shambles,’ said Sal, glancing at the phone. Two minutes. Perfect. ‘Thought they were meant to be good this year.’

‘Believe it when I see it,’ said Arnie, with a low laugh, raising the magic card to the sensor.

Meghan was already at work, looking – as usual – like she’d slept in the office overnight. Hair unwashed and hanging listlessly at her shoulders; owlish, unflattering glasses. Meghan was one of these girls who could probably look great with even twenty minutes’ effort: she had great boobs, her skin had that smooth uncomplicated quality of someone who hadn’t been kicked too hard by life yet – but she would never go to that effort. And Sal was aware of the irony of thinking these thoughts, when half her life was spent steering people away from objectification, so she naturally never said a thing about it.

‘So just to flag up, you’ve got the ABC interview after lunch, and then a car is coming to pick you up for the rehearsal, and there’s that other interview, which is a phoner, which is about women heroes in the workplace?’

As usual, Meghan laid no particular stress on the final five words, exciting as they might have sounded to an outsider: Sally often thought that she could have the phrase ‘rescue drowning man’ in the diary and Meghan wouldn’t read them with any emotion. Tonally, the only thing that differentiated her from a robot assistant, like Alexa, was the modern tendency to slope upwards at the end of sentences, as if everything was a question.

‘OK,’ said Sal, ‘and then we head for the dinner at …’

‘At six-thirty, they want you there seven for the drinks reception, your actual speech is nine?’ said Meghan, not even glancing down at these details on the screen in front of her. ‘I’ll be with you obviously, but the cars are all booked. And Andrew, the guy you’re speaking to now? Just a heads-up that he’s arrived?’

‘Send him up.’ Sal slid the phone across the desk. She didn’t expect to see it again for a couple of hours, but then, very little of the day from now on would go as she had imagined.

*

‘… and why do you think we do obsess over running late? Shouldn’t we all be more chill about it? Do you worry people read your book and get judgey?’

Sure enough, straight for the cliché questions. It wasn’t a surprise; as soon as they shook hands, he’d made a quip about how he’d been scared to get coffee on the way here, in case he was late. Also: ‘chill’. ‘Chill’, as an adjective. The guy was in his forties, like her.

‘Well, it isn’t about “obsessing”. Time management is just one of the ways I try to help people focus on what’s most important. If you learn to prioritize, divide your priorities into simple lists of five, it’s—’

‘So this speech tonight, will you be nervous? Do you get stage fright?’

I mean for the love of God, thought Sal. It was one of her favourite inner cries.

‘Well, I’ve been giving speeches for quite a few years. Obviously, it does have its challenges, and part of what I try to do in my work is coach people who aren’t – sorry – who aren’t experienced in it.’

The hesitation had been provoked by the appearance of Meghan in the doorway, for the second time. With a slight angling of her head, Sal sent her away, as she had done ten minutes ago. Whatever it was, Meghan was experienced enough to sort it out, and Sal didn’t want to be in this room a minute longer than she needed to be. If she knocked the interview on the head by one, they’d have proper time for lunch, and she could go out and look at her speech notes and maybe even nip into Myer for foundation. Meghan’s eyes flickered behind the big round lenses, but she shut the door, noiselessly.

‘Tell me about Mind the Gap,’ said the journalist, at last, and Sal went gratefully into her bullet points. Women were still paid fourteen per cent less than men across Australia. So the point of this campaign … The journalist was nodding, making the occasional note, but it didn’t seem like much was going in. He was very likely wondering why he’d been nailed to do this on a Saturday lunchtime when he could be in a beer garden. Sal could see a doodle of a shark in the corner of the page. This was going to be one of those pieces that were super-light on content, heavy on what-I-did-with-my-weekend narrative. ‘Chiltern, unsurprisingly, calls me into the office at eleven-thirty on the dot.’ ‘Chiltern sips her green tea as she tells me that addressing an audience can sometimes be challenging.’

‘And that’s why – even though I do know it’s not the sexiest subject – I feel like for anyone with a woman in their life they care about, which is hopefully everyone … can I help you with something, Meghan?’

It was a jarring sentence to say out loud, an inversion of their natural relationship. Meghan wasn’t there so that Sal could help her with stuff. Sal wasn’t going to start being PA to her own PA. And yet here she was, in the doorway for the third time now, the hat-trick as Dec would say, glancing between the floor and Sal’s phone in her left hand. The overall effect of all this pantomime discretion far more distracting than if she’d just bloody come out and said whatever it was when she first walked in.

‘So, there’s a message you – I think you’d want to deal with it?’ said Meghan.

‘To do with what?’ It came out brusquer than Sal intended. But this wasn’t good. The journo was doodling, again, and Sal knew he was enjoying this, the human angle, the comic relief. He’d end up putting this in his piece, the prick. ‘Chiltern – famed for being in charge of her time – is visibly rattled when her assistant …’

Meghan hesitated.

‘Give me a clue at least, darl,’ said Sal, working hard to keep her tone humorous.

‘Your brother’s about to kill himself?’ said Meghan.

5

BERLIN, 01:27

MICHAELA ADLER

Michaela Adler’s phone was in her handbag. The incoming text lit the whole interior of the bag for a second, like a torch in a tent, but she didn’t read it straight away. I need to turn off some of my notifications, she told herself, once again. All her chat threads, Facebook, the pushy running app which still piped up every couple of days – ‘let’s go run! The best time is right now!’ Phillip didn’t like it when she was glancing at it all the time. Even though it was very often gallery business. And even though, as she liked to point out, ‘People do tend to do things by text sometimes, because it’s not 1995.’

Phillip was only four years older than her, just like James had been, but he enjoyed his caricature as a grumpy old man; played up to it with a certain glee. He feigned ignorance of Justin Bieber’s life and work, however many times the name came up; he went to the local government office to register to vote, even though you could do it in five minutes on the internet. He visited Facebook no more than once a week, which in this day and age meant you might as well be living on a desert island.

In this place, they probably were the oldest people. Phillip with his thick-rimmed Tom Ford specs slightly misted over in the warmth of the club. Michaela in a dress she would describe as pretty revealing, but which by the standards of the 18-year-olds here might as well be a spacesuit.

The place had been a power plant before the Wall came down. The mezzanine was lit by bare bulbs that poked out on wires between the exposed girders of the ceiling. Michaela and Phillip often came here for late drinks. The throb of music from the floor below always made them grateful they didn’t have to dance, didn’t have to ‘go out’, try to meet someone. When they finally did go home they would joke about how they’d outlasted all the teenagers, who came out full of talk but by one in the morning were slumped in alleys outside, texting, sobbing, vomiting.

Maybe this would have to stop if Michaela got pregnant. When she got pregnant. But this was a good consolation prize for now. There was time. Occasionally she did get scared that there wasn’t as much time as there should be. People on the internet told horror stories about what happened if you left it past 35. If you had to have treatments. But, as Phillip said, ‘Everything is horror stories on the internet. Remember when you googled the pain in your side, it looked for half an hour like cancer, but it turns out you just had a pain in your side.’

She’d never met anyone whose opinion she deferred to so automatically, wanted to defer to. When they came out of a film she waited to hear what he thought, and tinkered with her own review automatically. If there was a weird noise in the night, she would nudge him awake just so he could say it was nothing, it was just the building. None of this was very feminist, probably, but in all her previous relationships – including with James – she’d always been the one to take the lead. It was tiring, being that person. It had been a fun couple of years on the other side of it. Couple of years and counting.

Of course, she hadn’t been able to articulate all this to James when she left him for Phillip. The conversation, the horrible bombshell dropped over a dinner: it had all been a mess. Her explanation had been a mess – it’s not that he’s better than you, I just need to see what’s out there, I can’t live not knowing. Her face had been a mess, too – mascara all over it like a kid’s crayon strokes. He hadn’t known how to react because she hardly knew what she was saying. Her reasons for running away to Phillip had only become clear months after the event. In fact, they were still becoming clear now. But if she had to describe what she loved about him in one sentence, it would be something to do with this – with the way they never ran out of stuff to talk about; they just saw five new conversational doors with every one they walked through. It was like a feast where, the more you ate, the more dishes reappeared. Mum used to tell her a Dominican folk tale which went something like that, though she couldn’t remember the moral.

Tonight, they had been talking about a friend with an online gambling problem so bad that there was talk of a plan to confront him for his own good. He’d just lost €2,000 in five seconds by betting online on a netball match which he wasn’t even watching. They’d also touched briefly on the Brexit debacle. Whether it would ever be sorted out or, as Phillip put it in his wiry voice, ‘the same people will be arguing the shit out of it until we all die from the temperature anyway’. In the last few minutes they’d been discussing a new exhibition at the gallery called ‘Denim World’, which featured nothing but a hundred pairs of jeans, worn by people in a hundred different countries. As with most work of this kind, Michaela wasn’t really sure whether it was interesting, or absolute horseshit, but as usual she’d written a press release which went big on the former.

It was twenty minutes after James sent the text that his former girlfriend glanced down to see the phone light up again in the bag, as it kept doing at intervals if you ignored a text – as if to say excuse me, I thought we were a team. She pulled the phone out, still only half-curious.

The sight of James’s number was a real surprise. Any interactions between them these days – minor queries about the upkeep of the flat – were conducted by email, and with no discussion of anything other than the matter in hand. She’d even officially deleted his number, because of a commitment to Phillip that this would be a fresh start for both of them. All the same, she naturally recognized those last three digits: 997. There was the satisfaction of having been thought of, and a little intrigue. Then she read the words and went cold.

‘I’ll just, I need to …’ she said, rising a little too quickly. Phillip nodded, taking a final contented sip of his beer. As she headed down the spiral staircase, he was inspecting the brickwork, etched here and there with the names of old lovers.

The toilet stalls were all taken and there was a queue, and a soundscape familiar to Michaela even though it wasn’t her language: high, urgent chatter, amped-up Friday-night emotion, over the shadow of the music from outside. She propped herself against a sink and read the message again.

I’ve decided to end my life. I’m fine. The understatement of it was so like him, in a way. But the actual sentiments couldn’t be right, couldn’t be real. He couldn’t have written this – she checked – almost half an hour ago, almost half a fucking hour. She pictured his round, earnest face, the curly fringe he was always toying with, to no real effect. She jabbed at the green icon to call his number.

The person she had called was not available. What did that mean? Where was ‘the person’, she asked herself, adrenalin hammering its way down her neural pathways. Was the phone at the bottom of a ravine with him? Was it wedged in his pocket in some hotel room as he hung from …?

No, this was stupid. Michaela was good in these situations; at least she thought she was. She might not be well organized, she might once have called the police to break her into her house when the keys were in her bra all along, but she believed in herself when real crises arrived. She was a go-to for panicky friends; she could do CPR and sometimes fantasized about becoming a hero by carrying it out, normally on the film star Tom Hanks. She’d even put ‘crisis management’ as a skill on her job application to the gallery. During the interview it had, sure enough, come up. They asked her what she’d do if fire damaged an exhibit the night before opening. ‘It’s a stupid question,’ Phillip had scoffed, ‘how often do they think that comes up? Why not ask what happens if a dinosaur gets in?’

Anyway, this was likely not a real crisis. He didn’t mean it. It was some sort of a stunt, or a drunken gesture.

Michaela’s stomach told her she didn’t believe herself. James never really got drunk, and it was hard to think of someone less likely to attempt a ‘stunt’. James was not a stuntman; he was a ponderer. He’d once caused a Monopoly game to be abandoned by deliberating so long over a hotel purchase that their guests went home.

‘Do you think we ruined Kath’s night?’ Michaela had asked as they washed up together afterwards.

‘She ruined her own night,’ said James, as they fought a tug-of-war over the tea towel. ‘How can she be married to someone who puts houses down without any sort of strategy?’

And two years later, when she marvelled over his shoulder at a spreadsheet showing that their new company had made a monthly profit for the first time, despite all her night terrors, he turned and grinned. ‘See? There’s no better way of choosing a partner than Monopoly skill. Never mind looks or being slim, or. You know. Having good one-liners at a party. No: Monopoly, clean driving licence. It’s all you need.’

It didn’t seem possible that the same person who’d spoken those words was the person making dire threats by text, threats to himself. She pressed green to call again. The recorded message repeated itself. She brought the phone down hard on the dirty-white edge of the sink. The petulance of it surprised her. It crossed Michaela’s mind that she was more pissed than she’d thought. She eyed herself uneasily in the mirror and moved aside to let a Goth girl wash her hands.

There was no point in panicking, she told herself again. Her legs felt leaden, as if the staircase was ten times as long as it had been on the way down. The reason it went to voicemail was that someone else was already talking him down. Yes. That was it; that made sense. Karl would be on it. Or Sally. Michaela gritted her teeth at the memory of the sister. Well. Someone. Someone would be dealing with this.

Phillip had ordered more beers and was already well into his. James would never have done that. He would have ordered the drinks, yes, but he would never start without someone else. He could be at a banquet in the last days of the Roman Empire and he still wouldn’t have touched so much as a dormouse until everyone was served. It was something she liked about him, one of the things she noticed first. An old-fashioned gentleman, her mum had said.

‘What’s up?’ asked Phillip.

‘Nothing.’

‘Clearly it’s not nothing.’

She hated it almost as much as she liked it, the ease with which Phillip could read her.

‘I just had … I had a weird message. From … James.’

Phillip raised his thick eyebrows. There was no reproach in the look – more a sort of quizzical amusement – and you would have to know Phillip as well as she did to realize that he was slightly hurt.

‘I thought that you didn’t …’

‘I don’t have his number. Any more. I can’t stop him having mine, can I? It wasn’t even to me. It was to … well, it looks like everyone.’

Her boyfriend’s eyes went rapidly over the text. It was easy to forget that English wasn’t his first language. She’d worked hard even to get to her passable level of German, and almost everyone at the gallery spoke English with a proficiency which made that effort seem pointless. They sprinkled English phrases into their conversation: online. Hanging out. Sometimes when Michaela was around, they spoke in English to each other, as if it was such a minor adjustment it wasn’t even worth mentioning. Last week her boss Anneka had used the English phrase cognitive dissonance in a meeting, and nobody flinched; Michaela had had to google it in the toilet later.

Phillip looked up from the phone with an expression whose rancour was a nasty surprise to her. It was such a handsome face, though, that even scowling suited him. He looked like a king disappointed with his dinner.

‘That is absolutely a dick thing to do,’ said Phillip. ‘That’s not fine.’

‘I know, but …’

‘He needs to grow up instead of sending something like this for attention.’

‘But I’m … that’s why I’m worried. I don’t think that’s the sort of thing he’d do, at all. I’m worried he might mean it.’

‘He doesn’t mean it,’ said Phillip, handing back the phone.

‘He might mean it. He isn’t the type to … he’s not melodramatic at all.’

Phillip blinked. Again, he didn’t have to say anything. Why are you defending your ex? his face asked. Most people in his position would ask the same, she supposed. Michaela was even wondering it herself, and perhaps that was what James would want. So maybe it was true; maybe it was manipulative of him to be doing this. She wondered fleetingly what James looked like these days; whether he had put all the weight back on by now.

‘Well, do you want to call him?’ asked Phillip.

Michaela moistened her lips with her tongue. Her throat felt dry. Below, there was a gap in the music; then a thudding beat came in, louder than anything before, and there were faint whoops from the dance floor. She could see James in the doorway for a second, as she had left him in the doorway of the old flat, shoulders drooping, and head held between his big hands. Her feeling of guilt and relief as she walked away.