Полная версия

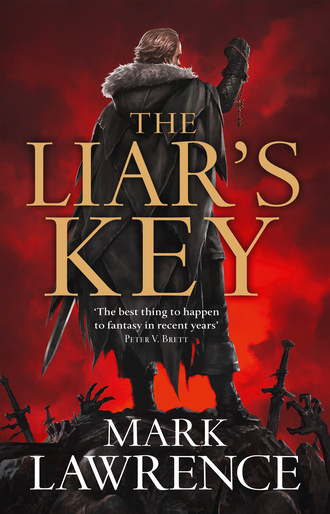

The Liar’s Key

I recalled how wide the wolf’s mouth had been around Snorri, and the lack of chewing going on. Closing my eyes I saw that brilliant hand pressed between the wolf’s eyes.

‘I want to see the creature.’ I didn’t, but I needed to. Besides, it wasn’t often I got to play the hero and it probably wouldn’t last long past Snorri regaining his senses. With some effort I managed to stand. Drawing breath proved the hardest part, the wolf had left me with bruised ribs on both sides. I was lucky it hadn’t crushed them all. ‘Hell! Where’s Tuttugu?’

‘I’m here!’ The voice came from behind several broad backs. Men pulled aside to reveal the other half of the Undoreth, grinning, one eye closing as it swelled. ‘Got knocked into a wall.’

‘You’re making a habit of that.’ It surprised me how pleased I was to see him in one piece. ‘Let’s go!’

Borris led the way, and flanked by men bearing reed torches I hobbled after, clutching my ribs and cursing. A pyramidal fire of seasoned logs now lit the square and a number of injured men were laid out on pallets around it, being treated by an ancient couple, both shrouded in straggles of long white hair. I hadn’t thought from my brief time in the hall that anyone had survived, but a wounded man has an instinct for rolling into any cranny or hidey hole that will take him. In the Aral Pass we’d pulled dead men from crevices and fox dens, some with just their boots showing.

Borris took us past the casualties and up to the doors of the great hall. A small man with a big warty blemish on his cheek waited guard, clutching his spear and eyeing the night.

‘It’s dead!’ The first thing he said to us. He seemed distracted, scratching at his overlarge iron helm as if that might satisfy whatever itched him.

‘Well of course it’s dead!’ Borris said, pushing past. ‘The berserker prince killed it!’

‘Of course it’s dead,’ I echoed as I passed the little fellow, allowing myself a touch of scorn. I couldn’t say why the thing had chosen that moment to fall on me, but its weight had driven my sword hilt-deep, and even a wolf as big as a horse isn’t going to get up again after an accident like that. Even so, I felt troubled. Something about Snorri’s hands glowing like that…

‘Odin’s balls! It stinks!’ Borris, just ahead of me.

I drew breath to point out that of course it did. The hall had stunk to heaven but to be fair it had been only marginally worse than the aroma of Borris’s roundhouse, or in fact Olaafheim in general. My observations were lost in a fit of choking though as the foulness invaded my lungs. Choking with badly bruised ribs is a painful affair and takes your mind off things, like standing up. Fortunately Tuttugu caught hold of me.

We advanced, breathing in shallow gasps. Lanterns had been lit and placed on the central table, now set back on its feet. Some kind of incense burned in pots, cutting through the reek with a sharp lavender scent.

The dead men had been laid out before the hearth, parts associated. I saw Gauti among them, bitten clean in half, his eye screwed shut in the agony of the moment, the empty socket staring at the roof beams. The wolf lay where it had fallen whilst savaging Snorri. It sprawled on its side, feet pointing at the wall. The terror that had infected me when I first saw it now returned in force. Even dead it presented a fearsome sight.

The stench thickened as we approached.

‘It’s dead,’ Borris said, walking toward the dangerous end.

‘Well of course—’ I broke off. The thing reeked of carrion. Its fur had fallen out in patches, the flesh beneath grey. In places where it had split worms writhed. It wasn’t just dead – it had been dead for a while.

‘Odin…’ Borris breathed the word through the hand over his face, finding no parts of the divine anatomy to attach to the oath this time. I joined him and stared down at the wolf’s head. Blackened skull would be a more accurate description. The fur had gone, the skin wrinkled back as if before a flame, and on the bone, between eye sockets from which ichor oozed, a hand print had been seared.

‘The Dead King!’ I swivelled for the door, sword in fist.

‘What?’ Borris didn’t move, still staring at the wolf’s head.

I paused and pointed toward the corpses. As I did so Gauti’s good eye snapped open. If his stare had been cold in life now all the winters of the Bitter Ice blew there. His hands clawed at the ground, and where his torso ended, in the red ruin hanging below his ribcage, pieces began to twitch.

‘Burn the dead! Dismember them!’ And I started to run, clutching my sides with one arm, each breath sharp-edged.

‘Jal, where—’ Tuttugu tried to catch hold of me as I passed him.

‘Snorri! The Dead King sent the wolf for Snorri!’ I barged past wart-face on the door and out into the night.

What with my ribs and Tuttugu’s bulk neither of us was the first to get back to Borris’s house. Swifter men had alerted the wife and daughters. Locals were already arriving to guard the place as we ducked in through the main entrance. Snorri had got himself into a sitting position, showing off the over-muscled topology of his bare chest and stomach. He had the daughters fussing around him, one stitching a tear on his side while another cleaned a wound just below his collarbone. I remembered when I had been light-sworn, carrying Baraqel within me, just how much it took out of me to incapacitate a single corpse man. Back on the mountainside just past Chamy-Nix, when Edris’s men had caught us, I’d burned through the forearms of the corpse that had been trying to strangle me. The effort had left me helpless. The fact that Snorri could even sit after incinerating the entire head of a giant dead-wolf spoke as loudly about his inner strength as all that muscle did about his outer strength.

Snorri looked up and gave me a weary grin. Having been at different times both light-sworn and now dark-sworn I have to say the dark side has it easier. The power Snorri and I had used on the undead was the same healing that we had both used to repair wounds on others. It drew on the same source of energy, but healing undead flesh just burns the evil out of it.

‘It came for the key,’ I said.

‘Probably died on the ice and was released by the thaw.’ Snorri winced as the kneeling daughter set another stitch. ‘The real question is how did it know where to find us?’

It was a good question. The idea that any dead thing to hand might be turned against us at any point on our journey was not one that sat well with me. A good question and not one I had an answer for. I looked at Tuttugu as if he might have one.

‘Uh.’ Tuttugu scratched his chins. ‘Well it’s not exactly a secret that Snorri left Trond sailing south. Half the town watched.’ Tuttugu didn’t add ‘thanks to you’ but then again he didn’t need to. ‘And Olaafheim would be the first sensible place for three men in a small boat to put in. Easily reachable in a day’s sailing with fair winds. If he had an agent in town with some arcane means of communication … or maybe necromancers camped nearby. We don’t know how many escaped the Black Fort.’

‘Well that makes sense.’ It was a lot better than thinking the Dead King just knew where to find us any time he wanted. ‘We should, uh, probably leave now.’

‘Now?’ Snorri frowned. ‘We can’t sail in the middle of the night.’

I stepped in close, aware of the two daughters’ keen interest. ‘I know you’re well liked here, Snorri. But there’s a pile of dead bodies in the great hall, and when Borris and his friends have finished dismembering and burning their friends and family they might think to ask why this evil has been visited upon their little town. Just how good a friend is he? And if they start asking questions and want to take us upriver to meet these two jarls of theirs … well, do you have friends in high places too?’

Snorri stood, towering above the girls, and me, pulling on his jerkin. ‘Better go.’ He picked up his axe and started for the door.

Nobody moved to stop us, though there were plenty of questions.

‘Need to get something from the boat.’ I said that a lot on the way down to the harbour. It was almost true.

By the time we reached the seafront we had quite a crowd with us, their questions merging into one seamless babble of discontent. Tuttugu kept a reed-torch from Borris’s roundhouse, lighting the way around piled nets and discarded crates. The locals, lost in the surrounding shadows, watched on in untold numbers. A man grabbed at my arm, saying something about waiting for Borris. I shook him off.

‘I’ll check in the prow!’ It took me a while to master the nautical terminology but ever since learning prow from stern I took all opportunities to demonstrate my credentials. I clambered down, gasping at the pain that reaching overhead caused. I could hear mutters above, people encouraging each other to stop us leaving.

‘It might be in the stern … that … thing we need.’ Tuttugu could take acting lessons from a troll-stone. He dropped into the other end of the boat, causing a noticeable tilt.

‘I’ll row us away,’ Snorri said, descending in two steps. He really hadn’t got the hang of deception yet, which after nearly six months in my company had to say something bad about my teaching skills.

To distract the men at the harbour wall from the fact we were smoothly pulling away into the night I raised a hand and bid them a royal farewell. ‘Goodbye, citizens of Olaafheim. I’ll always remember your town as … as … somewhere I’ve been.’

And that was that. Snorri kept rowing and I slumped back down into the semi-drunken stupor I’d been enjoying before all the night’s unpleasantness started. Another town full of Norsemen left behind me. Soon I’d be lazing in the southern sun. I’d almost certainly marry Lisa and be spending her father’s money before the summer was out.

Three hours later dawn found us out in the wide grey wilderness of the sea, Norseheim a black line to the east, promising nothing good.

‘Well,’ I said. ‘At least the Dead King can’t get at us out here.’

Tuttugu leaned out to look at the wine dark waves. ‘Can dead whales swim?’ he asked.

6

Our hasty departure from Olaafheim saw us putting in two days later at the port of Haargfjord. Food supplies had grown low and although Snorri wanted to avoid any of the larger towns Haargfjord seemed to be our only choice.

I patted our bag of provisions. ‘Seems early to restock,’ I said, finding it more empty than full. ‘Let’s get some decent vittles this time. Proper bread. Cheese. Some honey maybe…’

Snorri shook his head. ‘It would have lasted me to Maladon. I wasn’t planning on feeding Tuttugu, or having you borrow rations then spit them out into the sea.’

We tied up in the harbour and Snorri set me at a table in a dockside tavern so basic that it lacked even a name. The locals called it the dockside tavern and from the taste of the beer they watered it with what they scooped from the holds of ships at the quays. Even so, I’m not one to complain and the chance to sit somewhere warm that didn’t rise and fall with the swell, was one I wasn’t about to turn down.

I sat there all day, truth be told, swigging the foul beer, charming the pair of plump blonde serving-girls, and devouring most of a roast pig. I hadn’t expected to be left so long but before I knew it I had reached that number of ales where you blink and the sun has leapt a quarter of its path between horizons.

Tuttugu joined me late in the afternoon looking worried. ‘Snorri’s vanished.’

‘A clever trick! He should teach me that one.’

‘No, I’m serious. I can’t find him anywhere, and it’s not that big a town.’

I made show of peering under the table, finding nothing but grime-encrusted floorboards and a collection of rat-gnawed rib-bones. ‘He’s a big fellow. I’ve not known a man better at looking after himself.’

‘He’s on a quest to open death’s door!’ Tuttugu said, waving his hands to demonstrate how that was the opposite of looking after oneself.

‘True.’ I handed Tuttugu a legbone thick with roast pork. ‘Look at it this way. If he has come to grief he’s saved you a journey of months… You can go home to Trond and I’ll wait here for a decent sized ship to take me to the continent.’

‘If you’re not worried about Snorri you might at least be worried about the key.’ Tuttugu scowled and took a huge bite from the pig leg.

I raised a brow at that but Tuttugu’s mouth was full and I was too drunk to hold on to any questions I might have.

‘Why are you even doing this, Tuttugu?’ I ran ale over my loose tongue. ‘Hunting a door to Hell? Are you planning to follow him in if he finds it?’

Tuttugu swallowed. ‘I don’t know. If I’m brave enough I will.’

‘Why? Because you’re from the same clan? You lived on the slopes of the same fjord? What on earth would possess you to—’

‘I knew his wife. I knew his children, Jal. I bounced them on my knee. They called me “uncle”. If a man can let go of that he can let go of anything … and then what point is there to his life, what meaning?’

I opened my mouth, but even drunk I hadn’t answers to that. So I lifted my tankard and said nothing.

Tuttugu stayed long enough to finish my meal and drink my ale, then left to continue his search. One of the beer-girls, Hegga or possibly Hadda, brought another pitcher and the next thing I knew night had settled around me and the landlord had started making loud comments about people getting back to their own homes, or at least paying over the coin for space on his fine boards.

I heaved myself up from the table and staggered off to the latrine. Snorri was sitting in my place when I came back, his brow furrowed, an angry set to his jaw.

‘Snolli!’ I considered asking where he’d been but realized that if I were too drunk to say his name I’d best just sit down. I sat down.

Tuttugu came through the street doors moments later and spotted us with relief.

‘Where have you been?’ Like a mother scolding.

‘Right here! Oh—’ I swivelled around with exaggerated care to look at Snorri.

‘Seeking wisdom,’ he said, turning to narrow blue eyes in my direction, a dangerous look that managed to sober me up a little. ‘Finding my enemy.’

‘Well that’s never been a problem,’ I said. ‘Wait a while and they’ll come to you.’

‘Wisdom?’ Tuttugu pulled up a stool. ‘You’ve been to a völva? Which one? I thought we were headed for Skilfar at Beerentoppen?’

‘Ekatri.’ Snorri poured himself some of my ale. Tuttugu and I said nothing, only watched him. ‘She was closer.’ And into our silence Snorri dropped his tale, and afloat on a sea of cheap beer I saw the story unfold before me as he spoke.

After leaving me in the dockside tavern Snorri had gone over the supply list with Tuttugu. ‘You got this, Tutt? I need to go up and see Old Hrothson.’

‘Who?’ Tuttugu looked up from the slate where Snorri had scratched the runes for salt, dried beef, and the other supplies, together with tally marks to count the quantities.

‘Old Hrothson, the chief!’

‘Oh.’ Tuttugu shrugged. ‘My first time in Haargfjord. Go, I can haggle with the best of them.’

Snorri slapped Tuttugu’s arm and turned to go.

‘Of course even the best haggler needs something to pay with…’ Tuttugu added.

Snorri fished in the pocket of his winter coat and pulled out a heavy coin, flipping it to Tuttugu.

‘Never seen a gold piece that big before.’ Tuttugu held it up to his face, so close his nose almost bumped it, the other hand buried in his ginger beard. ‘What’s that on it? A bell?’

‘The great bell of Venice. They say beside the Bay of Sighs you can hear it ring on a stormy night, though it lies fifty fathoms drowned.’ Snorri felt in his pocket for another of the coins. ‘It’s a florin.’

‘Great bell of where?’ Tuttugu turned the florin over in his hand, entranced by the gleam.

‘Venice. Drowned like Atlantis and all the cities beneath the Quiet Sea. It was part of Florence. That’s where they mint these.’

Tuttugu pursed his lips. ‘I’ll find Jal when I’m done. That’s if I can carry all the change I get after spending this beauty. I’ll meet you there.’

Snorri nodded and set off, taking a steep street that led away from the docks to the long halls on the ridge above the main town.

In his years of warring and raiding Snorri had learned the value of information over opinion, learned that the stories people tell are one thing but if you mean to risk the lives of your men it’s better to have tales backed up by the evidence of your eyes – or those of a scout. Better still several scouts, for if you show a thing to three men you’ll hear three different accounts, and if you’re lucky the truth will lie somewhere between them. He would go to Skilfar and seek out the ice witch in her mountain of fire, but better to go armed with advice from other sources, rather than as an empty vessel waiting to be filled with only her opinion.

Old Hrothson had received Snorri in the porch of his long hall, where he sat in a high-backed chair of black oak, carved all over with Asgardian sigils. On the pillars rising above him the gods stood, grim and watchful. Odin looked out over the ancient’s bowed head, Freja beside him, flanked by Thor, Loki, Aegir. Others, carved lower down, stood so smoothed by years of touching that they might be any god you cared to name. The old man sat bowed under his mantle of office, all bones and sunken flesh, thin white hair crowning a liver-spotted pate, and a sharp odour of sickness about him. His eyes, though, remained bright.

‘Snorri Snagason. I’d heard the Hardassa put an end to the Undoreth. A knife in the back on a dark night?’ Old Hrothson measured out his words, age creaking in each syllable. The younger Hrothson sat beside him in a lesser chair, a silver-haired man of sixty winters. Honour guards clad in chainmail and furs flanked them, long axes resting against their shoulders. The two Hrothsons had sat here when Snorri last saw them, maybe five years earlier, gazing down across their town and out to the grey sea.

‘Two only survived,’ Snorri said. ‘Myself and Olaf Arnsson, known as Tuttugu.’

The older Hrothson leaned forward and hawked up a mess of dark phlegm, spitting it to the boards. ‘That for the Hardassa. Odin grant you vengeance and Thor the strength to take it.’

Snorri clapped his fist to his chest though the words gave him no comfort. Thor might be god of strength and war, Odin of wisdom, but he sometimes wondered if it wasn’t Loki, the trickster god, who stood behind what unfolded. A lie can run deeper than strength or wisdom. And hadn’t the world proved to be a bitter joke? Perhaps even the gods themselves lay snared in Loki’s greatest trick and Ragnarok would hear the punch line spoken. ‘I seek wisdom,’ he said.

‘Well,’ said Old Hrothson. ‘There’s always the priests.’

All of them laughed, even the honour guards.

‘No really,’ the younger Hrothson spoke for the first time. ‘My father can advise you about war, crops, trade and fishing. Do you speak of the wisdom of this world or the other?’

‘A little of both,’ Snorri admitted.

‘Ekatri.’ Old Hrothson nodded. ‘She has returned. You’ll find her winter hut by the falls on the south side, three miles up the fjord. There’s more in her runes than in the smokes and iron bells of the priests with their endless tales of Asgard.’

The son nodded, and Snorri took his leave. When he glanced back both men were as they had been when he left them five years before, gazing out to sea.

An hour later Snorri approached the witch’s hut, a small roundhouse, log-built, the roof of heather and hide, a thin trail of smoke rising from the centre. Ice still fringed the falls, crashing down behind the hut in a thin and endless cascade, pulses of white driving down through the mist above the plunge pool.

A shiver ran through Snorri as he followed the rocky path to Ekatri’s door. The air tasted of old magic, neither good nor ill, but of the land, having no love for man. He paused to read the runes on the door. Magic and Woman. Völva it meant. He knocked and, hearing nothing, pushed through.

Ekatri sat on spread hides, almost lost beneath a heap of patched blankets. She watched him with one dark eye and a weeping socket. ‘Come in then. Clearly you’re not taking no answer for an answer.’

Snorri ducked low to avoid the door lintel and then to clear the herbs hanging from the roof stays in dry bunches. The small fire between them coiled its smoke up into the funnel of the roof, filling the single room with a perfume of lavender and pine that almost obscured the undercurrent of rot.

‘Sit, child.’

Snorri sat, taking no offence. Ekatri looked to be a hundred, as wizened and twisted as a clifftop tree.

‘Well? Do you expect me to guess?’ Ekatri dipped her clawed hand into one of the bowls set before her and tossed a pinch of the powder into the embers before her, putting a darker curl into the rising smoke.

‘In the winter assassins came to Trond. They came for me. I want to know who sent them.’

‘You didn’t ask them?’

‘Two I had to kill. The last I disabled, but I couldn’t make him speak.’

‘You’ve no stomach for torture, Undoreth?’

‘He had no mouth.’

‘A strange creature indeed.’ Ekatri drew out a glass jar from her blanket, not a thing Northmen could make. A thing of the Builders, and in the greenish liquid within, a single eyeball, turning on the slow current. The witch’s own perhaps.

‘They had olive skin, were human in all respects save for the lack of a mouth, that and the ungodly quickness of them.’ Snorri drew out a gold coin from his pocket. ‘Might be from Florence. They had the blood price on them, in florins.’

‘That doesn’t make them Florentines. Half the jarls in Norseheim have a handful of florins in their warchests. In the southern states the nobles spend florins in their gambling halls as often as their own currency.’ Snorri passed the coin over into Ekatri’s outstretched claw. ‘A double florin. Now they are more rare.’

Ekatri set the coin upon the lid of the jar where her lost eye floated. She drew a leather bag from her blankets and shook it so the contents clacked against each other. ‘Put your hand in, mix them about, tip them out … here.’ She cleared a space and marked the centre.

Snorri did as he was bidden. He’d had the runes read for him before. This message would be a darker one, he fancied. He closed his hand around the tablets, finding them colder and heavier than he had expected, then drew his fist out, opened it palm up and let the rune stones slip from his hand onto the hides below. It seemed as though each fell through water, its path too slow, twisting more than it should. When they landed a silence ran through the hut, underwriting the finality of the pronouncement writ in stone between the witch and himself.

Ekatri studied the tablets, her face avid, as if hungry for something she might read among them. A very pink tongue emerged to wet ancient lips.

‘Wunjo, face down, beneath Gebo. A woman has buried your joy, a woman may release it.’ She touched another two face up. ‘Salt and Iron. Your path, your destination, your challenge and your answer.’ A gnarled finger flipped over the final runestone. ‘The Door. Closed.’

‘What does all that mean?’ Snorri frowned.

‘What do you think it means?’ Ekatri watched him with wry amusement.

‘Am I supposed to be the völva for you?’ Snorri rumbled, feeling mocked. ‘Where’s the magic if I tell you the answer?’

‘I let you tell me your future and you ask where the magic lies?’ Ekatri reached out and swirled the jar beside her so the pickled eyeball within spun with the current. ‘The magic might be in getting into that thick warrior skull of yours the fact that your future stands on your choices and only you can make them. The magic lies in knowing that you seek both a door and the happiness you think lies behind it.’

‘There’s more,’ Snorri said.

‘There is always more.’

Snorri drew up his jerkin. The scrapes and tears the Fenris wolf had given him were scabbed and healing, bruises livid across his chest and side, but across his ribs a long single slice lay glistening, the flesh about it an angry red, and along the wound’s length a white encrustation of salt. ‘My gift from the assassins.’