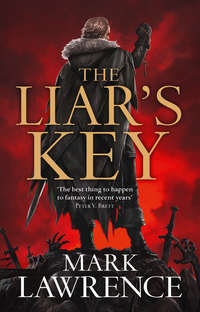

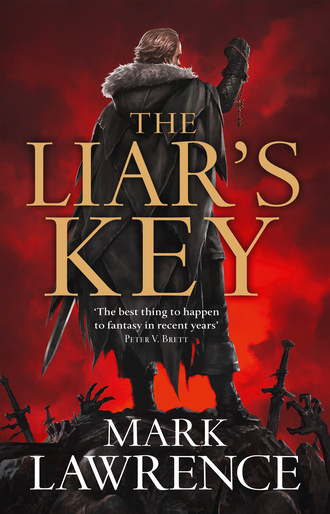

Полная версия

The Liar’s Key

‘I don’t see him.’ Snorri was normally easy to spot in a crowd – you just looked up.

‘There!’ Tuttugu tugged my arm and pointed to what must be the smallest boat at the quays, occupied by the largest man.

‘That thing? It’s not even big enough for Snorri!’ I hastened after Tuttugu anyway. There seemed to be some sort of disturbance up by the harbour master’s station and I could swear someone shouted ‘Kendeth!’

I overtook Tuttugu and clattered out along the quay to arrive well ahead of him above Snorri’s little boat. Snorri looked up at me through the black and windswept tangle of his mane. I took a step back at the undisguised mistrust in his stare.

‘What?’ I held out my hands. Any hostility from a man who swings an axe like Snorri does has to be taken seriously. ‘What did I do?’ I did recall some kind of altercation – though it seemed unlikely that I’d have the balls to disagree with six and a half foot of over-muscled madman.

Snorri shook his head and turned away to continue securing his provisions. The boat seemed full of them. And him.

‘No really! I got hit in the head. What did I do?’

Tuttugu came puffing up behind me, seeming to want to say something, but too winded to speak.

Snorri let out a snort. ‘I’m going, Jal. You can’t talk me out of it. We’ll just have to see who cracks first.’

Tuttugu set a hand to my shoulder and bent as close to double as his belly would allow. ‘Jal—’ Whatever he’d intended to say past that trailed off into a wheeze and a gasp.

‘Which of us cracks first?’ It started to come back to me. Snorri’s crazy plan. His determination to head south with Loki’s key … and me equally resolved to stay cosy in the Three Axes enjoying the company until either my money ran out or the weather improved enough to promise a calm crossing to the continent. Aslaug agreed with me. Every sunset she would rise from the darkest reaches of my mind and tell me how unreasonable the Norseman was. She’d even convinced me that separating from Snorri would be for the best, releasing her and the light-sworn spirit Baraqel to return to their own domains, carrying the last traces of the Silent Sister’s magic with them.

‘Jarl Sorren…’ Tuttugu heaved in a lungful of air. ‘Jarl Sorren’s men!’ He jabbed a finger back up the quay. ‘Go! Quick!’

Snorri straightened up with a wince, and frowned back at the dock wall where chain-armoured housecarls were pushing a path through the crowd. ‘I’ve no bad blood with Jarl Sorren…’

‘Jal does!’ Tuttugu gave me a hefty shove between the shoulder blades. I balanced for a moment, arms pin wheeling, took a half-step forward, tripped over that damn sword, and dived into the boat. Bouncing off Snorri proved marginally less painful than meeting the hull face first, and he caught hold of enough of me to make sure I ended in the bilge water rather than the seawater slightly to the left.

‘What the hell?’ Snorri remained standing a moment longer as Tuttugu started to struggle down into the boat.

‘I’m coming too,’ Tuttugu said.

I lay on my side in the freezing dirty water at the bottom of Snorri’s freezing dirty boat. Not the best time for reflection but I did pause to wonder quite how I’d gone so quickly from being pleasantly entangled in the warmth of Edda’s slim legs to being unpleasantly entangled in a cold mess of wet rope and bilge water. Grabbing hold of the small mast, I sat up, cursing my luck. When I paused to draw breath it also occurred to me to wonder why Tuttugu was descending toward us.

‘Get back out!’ It seemed the same thought had struck Snorri. ‘You’ve made a life here, Tutt.’

‘And you’ll sink the damn boat!’ Since no one seemed inclined to do anything about escaping I started to fit the oars myself. It was true though – there was nothing for Tuttugu down south and he did seem to have taken to life in Trond far more successfully than to his previous life as a Viking raider.

Tuttugu stepped backward into the boat, almost falling as he turned.

‘What are you doing here, Tutt?’ Snorri reached out to steady him whilst I grabbed the sides. ‘Stay. Let that woman of yours look after you. You won’t like it where I’m bound.’

Tuttugu looked up at Snorri, the two of them uncomfortably close. ‘Undoreth, we.’ That’s all he said, but it seemed to be enough for Snorri. They were after all most likely the last two of their people. All that remained of the Uuliskind. Snorri slumped as if in defeat then moved back, taking the oars and shoving me into the prow.

‘Stop!’ Cries from the quay, above the clatter of feet. ‘Stop that boat!’

Tuttugu untied the rope and Snorri drew on the oars, moving us smoothly away. The first of Jarl Scorron’s housecarls arrived red-faced above the spot where we’d been moored, roaring for our return.

‘Row faster!’ I had a panic on me, terrified they might jump in after us. The sight of angry men carrying sharp iron has that effect on me.

Snorri laughed. ‘They’re not armoured for swimming.’ He looked back at them, raising his voice to a boom that drowned out their protests, ‘And if that man actually throws the axe he’s raising I really will come back to return it to him in person.’

The man kept hold of his axe.

‘And good riddance to you!’ I shouted, but not so loud the men on the quay would hear me. ‘A pox on Norsheim and all its women!’ I tried to stand and wave my fist at them, but thought better of it after nearly pitching over the side. I sat down heavily, clutching my sore nose. At least I was heading south at last, and that thought suddenly put me in remarkably good spirits. I’d sail home to a hero’s welcome and marry Lisa DeVeer. Thoughts of her had kept me going on the Bitter Ice and now with Trond retreating into the distance she filled my imagination once again.

It seemed that all those months of occasionally wandering down to the docks and scowling at the boats had made a better sailor of me. I didn’t throw up until we were so far from port that I could barely make out the expressions on the housecarls’ faces.

‘Best not to do that into the wind,’ Snorri said, not breaking the rhythm of his rowing.

I finished groaning before replying, ‘I know that, now.’ I wiped the worst of it from my face. Having had nothing but a punch on the nose for breakfast helped to keep the volume down.

‘Will they give chase?’ Tuttugu asked.

That sense of elation at having escaped a gruesome death shrivelled up as rapidly as it had blossomed and my balls attempted a retreat back into my body. ‘They won’t … will they?’ I wondered just how fast Snorri could row. Certainly under sail our small boat wouldn’t outpace one of Jarl Sorren’s longships.

Snorri managed a shrug. ‘What did you do?’

‘His daughter.’

‘Hedwig?’ A shake of the head and laugh broke from him. ‘Erik Sorren’s chased more than a few men over that one. But mostly just long enough to make sure they keep running. A prince of Red March though … might go the extra mile for a prince, then drag you back and see you handfasted before the Odin stone.’

‘Oh God!’ Some other awful pagan torture I’d not heard about. ‘I barely touched her. I swear it.’ Panic starting to rise, along with the next lot of vomit.

‘It means “married”,’ said Snorri. ‘Handfasted. And from what I heard you barely touched her repeatedly and in her own father’s mead hall to boot.’

I said something full of vowels over the side before recovering myself to ask, ‘So, where’s our boat?’

Snorri looked confused. ‘You’re in it.’

‘I mean the proper-sized one that’s taking us south.’ Scanning the waves I could see no sign of the larger vessel I presumed we must be aiming to rendezvous with.

Snorri’s mouth took on a stiff-jawed look as if I’d insulted his mother. ‘You’re in it.’

‘Oh come on…’ I faltered beneath the weight of his stare. ‘We’re not seriously crossing the sea to Maladon in this rowboat are we?’

By way of answer Snorri shipped the oars and started to prepare the sail.

‘Dear God…’ I sat, wedged in the prow, my neck already wet with spray, and looked out over the slate-grey sea, flecked with white where the wind tore the tops off the waves. I’d spent most of the voyage north unconscious and it had been a blessing. The return would have to be endured without the bliss of oblivion.

‘Snorri plans to put in at ports along the coast, Jal,’ Tuttugu called from his huddle in the stern. ‘We’ll sail from Kristian to cross the Karlswater. That’s the only time we’ll lose sight of land.’

‘A great comfort, Tuttugu. I always like to do my drowning within sight of land.’

Hours passed and the Norsemen actually seemed to be enjoying themselves. For my part I stayed wrapped around the misery of a hangover, leavened with a stiff dose of stool-to-head. Occasionally I’d touch my nose to make sure Astrid’s punch hadn’t broken it. I’d liked Astrid and it sorrowed me to think we wouldn’t snuggle up in her husband’s bed again. I guessed she’d been content to ignore my wanderings as long as she could see herself as the centre and apex of my attentions. To dally with a jarl’s daughter, someone so highborn, and for it to be so public, must have been more than her pride would stand for. I rubbed my jaw, wincing. Damn, I’d miss her.

‘Here.’ Snorri thrust a battered pewter mug toward me.

‘Rum?’ I lifted my head to squint at it. I’m a great believer in hair of the dog, and nautical adventures always call for a measure of rum in my largely fictional experience.

‘Water.’

I uncurled with a sigh. The sun had climbed as high as it was going to get, a pale ball straining through the white haze above. ‘Looks like you made a good call. Albeit by mistake. If you hadn’t been ready to sail I might be handfasted by now. Or worse.’

‘Serendipity.’

‘Seren-what-ity?’ I sipped the water. Foul stuff. Like water generally is.

‘A fortunate accident,’ Snorri said.

‘Uh.’ Barbarians should know their place, and using long words isn’t it. ‘Even so it was madness to set off so early in the year. Look! There’s still ice floating out there!’ I pointed to a large plate of the stuff, big enough to hold a small house. ‘Won’t be much left of this boat if we hit any.’ I crawled back to join him at the mast.

‘Best not distract me from steering then.’ And just to prove a point he slung us to the left, some lethal piece of woodwork swinging scant inches above my head as the sail crossed over.

‘Why the hurry?’ Now that the lure of three delicious women who had fallen for my ample charms had been removed I was more prepared to listen to Snorri’s reasons for leaving so precipitously. I made a vengeful note to use ‘precipitously’ in conversation. ‘Why so precipitous?’

‘We went through this, Jal. To the death!’ Snorri’s jaw tightened, muscles bunching.

‘Tell me once more. Such matters are clearer at sea.’ By which I meant I didn’t listen the first time because it just seemed like ten different reasons to pry me from the warmth of my tavern and from Edda’s arms. I would miss Edda, she really was a sweet girl. Also a demon in the furs. In fact I sometimes got the feeling that I was her foreign fling rather than the other way around. Never any talk of inviting me to meet her parents. Never a whisper about marriage to her prince … A man enjoying himself any less than I was might have had his pride hurt a touch by that. Northern ways are very strange. I’m not complaining … but they’re strange. Between the three of them I’d spent the winter in a constant state of exhaustion. Without the threat of impending death I might never have mustered the energy to leave. I might have lived out my days as a tired but happy tavernkeeper in Trond. ‘Tell me once more and we’ll never speak of it again!’

‘I told you a hundr—’

I made to vomit, leaning forward.

‘All right!’ Snorri raised a hand to forestall me. ‘If it will stop you puking all over my boat…’ He leaned out over the side for a moment, steering the craft with his weight, then sat back. ‘Tuttugu!’ Two fingers toward his eyes, telling him to keep watch for ice. ‘This key.’ Snorri patted the front of his fleece jacket, above his heart. ‘We didn’t come by it easy.’ Tuttugu snorted at that. I suppressed a shudder. I’d done a good job of forgetting everything between leaving Trond on the day we first set off for the Black Fort and our arrival back. Unfortunately it only took a hint or two for memories to start leaking through my barriers. In particular the screech of iron hinges would return to haunt me as door after door surrendered to the unborn captain and that damn key.

Snorri fixed me with that stare of his, the honest and determined one that makes you feel like joining him in whatever mad scheme he’s espousing – just for a moment, mind, until commonsense kicks back in. ‘The Dead King will be wanting this key back. Others will want it too. The ice kept us safe, the winter, the snows … once the harbour cleared the key had to be moved. Trond would not have kept him out.’

I shook my head. ‘Safe’s the last thing on your mind! Aslaug told me what you really plan to do with Loki’s key. All that talk of taking it back to my grandmother was nonsense.’ Snorri narrowed his eyes at that. For once the look didn’t make me falter – soured by the worst of days and made bold by the misery of the voyage I blustered on regardless. ‘Well! Wasn’t it nonsense?’

‘The Red Queen would destroy the key,’ Snorri said.

‘Good!’ Almost a shout. ‘That’s exactly what she should do!’

Snorri looked down at his hands, upturned on his lap, big, scarred, thick with callus. The wind whipped his hair about, hiding his face. ‘I will find this door.’

‘Christ! That’s the last place that key should be taken!’ If there really was a door into death no sane person would want to stand before it. ‘If this morning has taught me anything it’s to be very careful which doors you open and when.’

Snorri made no reply. He kept silent. Still. Nothing for long moments but the flap of sail, the slop of wave against hull. I knew what thoughts ran through his head. I couldn’t speak them, my mouth would go too dry. I couldn’t deny them, though to do so would cause me only an echo of the hurt such a denial would do him.

‘I will get them back.’ His eyes held mine and for a heartbeat made me believe he might. His voice, his whole body shook with emotion, though in what part sorrow and what part rage I couldn’t say.

‘I will find this door. I will unlock it. And I will bring back my wife, my children, my unborn son.’

3

‘Jal?’ Someone shaking my shoulder. I reached to draw Edda in closer and found my fingers tangled in the unwholesome ginger thicket of Tuttugu’s beard, heavy with grease and salt. The whole sorry story crashed in on me and I let out a groan, deepened by the returning awareness of the swell, lifting and dropping our little boat.

‘What?’ I hadn’t been having a good dream, but it was better than this.

Tuttugu thrust a half-brick of dark Viking bread at me, as if eating on a boat were really an option. I waved it away. If Norse women were a highpoint of the far north then their cuisine counted as one of the lowest. With fish they were generally on a good footing, simple, plain fare, though you had to be careful or they’d start trying to feed it to you raw, or half rotted and stinking worse than corpse flesh. ‘Delicacies’ they’d call it … The time to eat something is the stage between raw and rotting. It’s not the alchemy of rockets! With meat – what meat there was to be found clinging to the near vertical surfaces of the north – you could trust them to roast it over an open fire. Anything else always proved a disaster. And with any other kind of eatable the Norsemen were likely to render it as close to inedible as makes no difference using a combination of salt, pickle, and desiccated nastiness. Whale meat they preserved by pissing on it! My theory was that a long history of raiding each other had driven them to make their foodstuffs so foul that no one in their right mind would want to steal it. Thereby ensuring that, whatever else the enemy might carry off, women, children, goats, and gold, at least they’d leave lunch behind.

‘We’re coming in to Olaafheim,’ Tuttugu said, pulling me out of my doze again.

‘Whu?’ I levered myself up to look over the prow. The seemingly endless uninviting coastline of wet black cliffs protected by wet black rocks had been replaced with a river mouth. The mountains leapt up swiftly to either side, but here the river had cut a valley whose sides might be grazed, and left a truncated floodplain where a small port nestled against the rising backdrop.

‘Best not to spend the night at sea.’ Tuttugu paused to gnaw at the bread in his hand. ‘Not when we’re so close to land.’ He glanced out west to where the sun plotted its descent toward the horizon. The quick look he shot me before settling back to eat told me clear enough that he’d rather not be sharing the boat with me when Aslaug came to visit at sunset.

Snorri tacked across the mouth of the river, the Hœnir he called it, angling across the diluted current toward the Olaafheim harbour. ‘These are fisher folk and raiders, Jal. Clan Olaaf, led by jarls Harl and Knütson, twin sons of Knüt Ice-Reaver. This isn’t Trond. The people are less … cosmopolitan. More—’

‘More likely to split my skull if I look at them wrong,’ I interrupted him. ‘I get the picture.’ I held a hand up. ‘I promise not to bed any jarl’s daughters.’ I even meant it. Now we were actually on the move I had begun to get excited about the prospect of a return to Red March, to being a prince again, returning to my old diversions, running with my old crowd, and putting all this unpleasantness behind me. And if Snorri’s plans led him along a different path then we’d just have to see what happened. We’d have to see, as he put it earlier, who cracked first. The bonds that bound us seemed to have weakened since the event at the Black Fort. We could separate five miles and more before any discomfort set in. And as we’d already seen, if the Silent Sister’s magic did fracture its way out of us the effect wasn’t fatal … except for other people. If push came to shove Aslaug’s advice seemed sound. Let the magic go, let her and Baraqel be released to return to their domains. It would be far from pleasant if last time was anything to go by, but like pulling a tooth it would be much better afterward. Obviously though, I’d do everything I could to avoid pulling that particular tooth – unless it meant traipsing into mortal danger on Snorri’s quest. My own plan involved getting him to Vermillion and having Grandmother order her sister to effect a more gentle release of our fetters.

We pulled into the harbour at Olaafheim with the shadows of boats at anchor reaching out toward us across the water. Snorri furled the sail, and Tuttugu rowed toward a berth. Fishermen paused from their labours, setting down their baskets of hake and cod to watch us. Fishwives laid down half-stowed nets and crowded in behind their men to see the new arrivals. Norsemen busy with some or other maintenance on the nearest of four longboats leaned out over the sides to call out in the old tongue. Threats or welcome I couldn’t tell, for a Viking can growl out the warmest greeting in a tone that suggests he’s promising to cut your mother’s throat.

As we coasted the last yard Snorri vaulted up onto the harbour wall from the side of the boat. Locals crowded him immediately, a sea of them surging around the rock. From the amount of shoulder-slapping and the tone of the growling I guessed we weren’t in trouble. The occasional chuckle even escaped from several of the beards on show, which took some doing as the Clan Olaaf grew the most impressive facial hair I’d yet seen. Many favoured the bushy explosions that look like regular beards subjected to sudden and very shocking news. Others had them plaited and hanging in two, three, sometimes five iron-capped braids reaching down to their belts.

‘Snorri.’ A newcomer, well over six foot and at least that wide, fat with it, arms like slabs of meat. At first I thought he was wearing spring furs, or some kind of woollen over-shirt, but as he closed on Snorri it became apparent that his chest hair just hadn’t known when to stop.

‘Borris!’ Snorri surged through the others to clasp arms with the man, the two of them wrestling briefly, neither giving ground.

Tuttugu finished tying up and with a pair of men on each arm the locals hauled him onto the dock. I clambered quickly up behind him, not wishing to be man-handled.

‘Tuttugu!’ Snorri pointed him out for Borris. ‘Undoreth. We might be the last of our clan, him and I…’ He trailed off, inviting any present to make a liar of him, but none volunteered any sighting of other survivors.

‘A pox on the Hardassa.’ Borris spat on the ground. ‘We kill them where we find them. And any others who make cause with the Drowned Isles.’ Mutters and shouts went up at that. More men spitting when they spoke the word ‘necromancer’.

‘A pox on the Hardassa!’ Snorri shouted. ‘That’s something to drink to!’

With a general cheering and stamping of feet the whole crowd started to move toward the huts and halls behind the various fisheries and boat sheds of the harbour. Snorri and Borris led the way, arms over each other’s shoulders, laughing at some joke, and I, the only prince present, trailed along unintroduced at the rear with the fishermen, their hands still scaly from the catch.

I guess Trond must have had its own stink, all towns do, but you don’t notice it after a while. A day at sea breathing air off the Atlantis Ocean tainted with nothing but a touch of salt proved sufficient to enable my nostrils to be offended by my fellow men once more. Olaafheim stank of fresh fish, sweat, stale fish, sewers, rotting fish, and uncured hides. It only got worse as we trudged up through a random maze of split-log huts, turf roofed and close to the ground, each with nets at the front and fuel stacked to the sheltered landward side.

Olaafheim’s great hall stood smaller than the foyer of my grandmother’s palace, a half timbered structure, mud daubed into any nook or cranny where the wind might slide its fingers, wooden shingles on the roof, patchy after the winter storms.

I let the Norsemen crowd in ahead of me and turned back to face the sea. In the west clear skies showed a crimson sun descending. Winter in Trond had been a long cold thing. I may have spent more time than was reasonable in the furs but in truth most of the north does the same. The night can last twenty hours and even when the day finally breaks it never gets above a level of cold I call ‘fuck that’ – as in you open the door, your face freezes instantly to the point where it hurts to speak, but manfully you manage to say ‘fuck that’, before turning round, and going back to bed. There’s little to do in a northern winter but to endure it. In the very depths of the season sunrise and sunset get so close together that if Snorri and I were to be in the same room Aslaug and Baraqel might even get to meet. A little further north and they surely would, for there the days dwindle into nothing and become a single night that lasts for weeks. Not that Aslaug and Baraqel meeting would be a good idea.

Already I could feel Aslaug scratching at the back of my mind. The sun hadn’t yet touched the water but the sea burned bloody with it and I could hear her footsteps. I recalled how Snorri’s eyes would darken when she used to visit him. Even the whites would fill with shadow, and become for a minute or two so wholly black that you might imagine them holes into some endless night, from which horrors might pour if he but looked your way. I held that to be a clash of temperaments though. If anything my vision always seemed clearer when she came. I made sure to be alone each sunset so we could have our moment. Snorri described her as a creature of lies, a seducer whose words could turn something awful into an idea that any reasonable man would consider. For my part I found her very agreeable, though perhaps a little excessive, and definitely less concerned about my safety than I am.