Полная версия

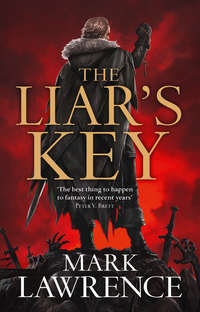

The Liar’s Key

‘An interesting injury.’ Ekatri reached forward with withered fingers. Snorri flinched but kept his place as she set her hand across the slit. ‘Does it hurt, Snorri ver Snagason?’

‘It hurts.’ Through gritted teeth. ‘It only gives me peace when we sail. The longer I stay put the worse it gets. I feel a … tug.’

‘It pulls you south.’ Ekatri removed her hand, wiping it on her furs. ‘You’ve felt this kind of call before.’

Snorri nodded. The bond with Jal exerted a similar draw. He felt it even now, slight, but there, wanting to pull him back to the tavern he’d left the southerner in.

‘Who has done this?’ He met the völva’s one-eyed gaze.

‘Why is a better question.’

Snorri picked up the stone Ekatri had named the Door. It no longer felt unduly cold or heavy, just a piece of slate, graven with a single rune. ‘Because of the door. And because I seek it,’ he said.

Ekatri held her hand out for the Door and Snorri passed the stone to her, feeling a twinge of reluctance at releasing it.

‘Someone in the south wants what you carry, and they want you to bring it to them.’ Ekatri licked her lips, again – the quickness of her tongue disturbing. ‘See how one simple cut draws all the runes together?’

‘The Dead King did this? He sent these assassins?’ Snorri asked.

Ekatri shook her head. ‘The Dead King is not so subtle. He is a raw and elemental force. This has an older hand behind it. You have something everyone wants.’ Ekatri touched the claw of her hand to her withered chest, the motion just glimpsed beneath the blankets. She touched on herself the same spot where Loki’s key lay against Snorri’s flesh.

‘Why just the three? Sent in the midst of winter. Why not more, now that travelling is easy?’

‘Perhaps he was testing something? Does it seem reasonable that three such assassins should fail against one man? Perhaps the wound was all they were intended to give you. An invitation … of a kind. If it wasn’t for the light within you battling the poison on that blade you would belong to the wound already, busy rushing south. There would be no question of any delay or diversion to speak to old women in their huts.’ She closed her eye and seemed to study Snorri with her empty socket a while. ‘They do say Loki’s key doesn’t like to be taken. Given, surely, but taken? Stolen, of a certainty. But taken by force? Some speak of a curse on those who own it through strength. And it doesn’t do to anger gods, now does it?’

‘I mentioned no key.’ Snorri fought to keep his hands from twitching toward it, burning cold against his chest.

‘Ravens fly even in winter, Snagason.’ Ekatri’s eye hardened. ‘Do you think if some southern mage knew of your exploits weeks ago old Ekatri would not know of it by now in her hut just down the coast? You came seeking wisdom: don’t take me for a fool.’

‘So I must go south and hope?’

‘There is no must about it. Surrender the key and the wound will heal. Perhaps even the wounds you can’t see. Stay here. Make a new life.’ She patted the hides beside her. ‘I could always use a new man. They never seem to last.’

Snorri made to stand. ‘Keep the gold, völva.’

‘Well, it seems my wisdom is valued today. Now that you’ve paid for it so handsomely perhaps you might heed it, child.’ She made the coin vanish and sighed. ‘I’m old, my bones are dry, the world has lost its savour, Snorri. Go, die, spend yourself in the deadlands … it matters little to me, my words are a pretty noise for you, your mind is set. The waste sorrows me, young and full of juice you are, but in the end, in the end we’re all wasted by the years. Think on it, though. Did those who stand in your path just start to covet Loki’s key this winter?’

‘I—’ Snorri knew a moment of shame. His thoughts had been so narrowed on the choice he’d made that the rest of the world had escaped him.

‘As your tragedies draw you south … wonder how those tragedies came to be and whose hand truly lay behind them.’

‘I’ve been a fool.’ Snorri found his feet.

‘And you’ll keep being one. Words can’t turn you from this course. Maybe nothing can. Friendship, love, trust, childish notions that have left this old woman … but, whatever the runes have to say, these are what rule you, Snorri ver Snagason, friendship, love, trust. They’ll drag you into the underworld, or save you from it. One or the other.’ She hung her head stared into the fire.

‘And this door I seek? Where can I find it?’

Ekatri’s wrinkle of a mouth puckered into consideration. ‘I don’t know.’

Snorri felt himself deflate. For a moment he had thought she might tell him, but it would have to be Skilfar. He started to turn.

‘Wait.’ The völva raised a hand. ‘I don’t know. But I can guess where it might lie. Three places.’ She returned her hand to her lap. ‘In Yttrmir the world slopes into Hel, so they say. In the badlands that stretch to the Yöttenfall the skies grow dim and the people strange. Go far enough and you’ll find villages where no one ages, none are born, each day follows the next without change. Further still and the people neither eat nor drink nor sleep but sit at their windows and stare. I’ve not heard that there is a door – but if you wish to go to Hel, that is a path. That is the first. The second is Eridruin’s Cave on the shore of Harrowfjord. Monsters dwell there. The hero Snorri Hengest fought them, and in his saga it speaks of a door that stands in the deepest part of those caverns, a black door. The third is less sure, told by a raven, a child of Crakk, white-feathered in his dotage. Even so. There is a lake in Scorron, the Venomere, dark as ink, where no fish swim. In its depths they say there is a door. In older days the men of Scorron threw witches into those waters, and none ever floated to the surface as corpses are wont to do.’

‘My thanks, völva.’ He hesitated. ‘Why did you tell me? If my plan is such madness?’

‘You asked. The runes put the door in your path. You’re a man. Like most men you need to face your quarry before you can truly decide. You won’t let go of this until you find it. Maybe not even then.’ Ekatri looked down and said no more. Snorri waited a moment longer, then turned and left, watched by a single eye floating in its jar.

‘Assassins?’ I lifted my head, the room continuing to move after I stopped. ‘Nonsense. You never mentioned any attack.’

Snorri lifted his jerkin. A single ugly wound ran down his side, far back, just past the ribs, salt crusted as he’d described. I may have seen it when Borris’s daughters were washing him back in Olaafheim after the Fenris wolf got hold of him, or perhaps he had been turned the wrong way … in any event I didn’t recall it in my inebriation.

‘So how much does it cost to hire assassins then?’ I asked. ‘Just for future reference. And … where’s the money? You should be rich!’

‘I gave most of it to the sea, so that Aegir would grant us safe passage,’ said Snorri.

‘Well that didn’t bloody work!’ I banged the table, perhaps a little harder than I meant to. I can be an excitable drunk.

‘Most of it?’ Tuttugu asked.

‘I paid a völva in Trond to treat the wound.’

‘Did a piss poor job from what I could see,’ I interjected, holding onto the table to keep from sliding past it.

‘It was beyond her skill, and while we stay here it only grows worse. Come, we’ll sail at dawn.’

Snorri stood and I guess we followed, though I’ve no memory of it.

7

I woke the next morning under sail and with a head sore enough to keep me curled in the prow groaning for the mercy of death until well past noon. The previous evening returned to me in fragments over the course of the next few days but it took an age to assemble the pieces into anything that made sense. And even then it didn’t make much sense. I consoled myself with our steady progress toward home and the civilized comforts thereof. As my head eased I planned out who I would see first and where I’d spend my first night. I would probably ask for Lisa DeVeer’s hand, assuming she hadn’t been dragged to the opera that night and burned with the rest. She was the finest of the old man’s daughters and I’d grown very fond of her. Especially in her absence. Thoughts of home kept me warm, and I huddled in the prow, waiting to get there.

The sea is always changing – but mostly for the worse. A cold and relentless rain arrived with the next morning and plagued us all day, driven by winds that pushed the ocean up before them into rolling hills of brine. Snorri’s dreadful little boat wallowed around like a pig trying to drown, and by the time evening threatened even the Norsemen had had enough.

‘We’ll put in at Harrowheim,’ Snorri told us, wiping the rain from his beard. ‘It’s a little place I know.’ Something about the name gave me a bad feeling but I was too eager to be on solid ground to object, and I guessed that even driven as he was the Norseman would rather spend the night ashore.

So, with the sun setting behind us we turned for the dark coastline, letting the wind hurl us toward the rocks until at the last the mouth of a fjord revealed itself and we sailed on in. The fjord proved itself a narrow one, little more than two hundred yards wide, its shores rising steeper than a flight of stairs, reaching for the serrated ridges of sullen rock that cradled the waters.

Aslaug spoke to me while the two Norsemen busied themselves with rope and sail. She sat beside me in the stern, clad in shadow and suggestion, impervious to the rain and the tug of the wind.

‘How they torment you with this boat, Prince Jalan.’ She laid a hand on my knee, ebony fingers staining the cloth, a delicious feeling soaking into me. ‘Baraqel guides Snorri now. The Norseman doesn’t have your strength of will. Where you were able to withstand the demon’s preaching Snorri is swayed. His instincts have always been—’

‘Demon?’ I muttered. ‘Baraqel’s an angel.’

‘You think so?’ She purred it close by my ear and suddenly I didn’t know what I thought, or care overmuch that I didn’t. ‘The creatures of the light wear whatever shapes you let them steal from legend. Beneath it all they are singular in will and no more your friend or guardians than the fire.’

I shivered in my cloak wishing I had a good blaze to warm myself by right now. ‘But fire is—’

‘Fire is your enemy, Prince Jalan. Enslave it and it will serve, but give it an inch, give it any opportunity, and you’ll be lucky to escape the burning wreckage of your home. You keep the fire at arms’ length. You don’t take a hot coal to your breast. No more should you embrace Baraqel or his kind. Snorri has done so and it has left his will in ashes – a puppet for the light to work its own purposes through. See how he looks at you. How he watches you. It’s only a matter of time before he acts openly against you. Mark these words, my prince. Mark—’

The sun sank and Aslaug fell into a darkness that leaked away through the hull.

We drew up at the quays of Harrowheim in the gathering gloom, guided in by the lights of houses clustered on the steepness of the slope. To the west some sort of cove or landslip offered a broad flattish area where crops might be grown in the shelter of the fjord.

An ancient with a lantern waved us alongside his own boat where he’d been sat picking the last fish from his nets.

‘You’ll be wannin’ me ta walk you up,’ he said, all gums and wisps of beard.

‘Don’t trouble yourself, Father.’ Tuttugu getting onto the quay with far more grace than he showed on land. He stooped low over the man’s boat. ‘Herring, eh? White-Gill. Nice catch. We don’t see them for another few weeks up in Trond.’

‘Ayuh.’ The old man held one up, still flipping half-heartedly in his fingers. ‘Good ’uns.’ He put it down as Snorri clambered out, leaving me to stagger uncertainly across the rolling boat toward the step. ‘Still. Better go with you. The lads are twitchy tonight. Raiders about – it’s the season for ’em. Might fill you full of spear before you know it.’

My boot, wet with bilge water, slipped out from under me at ‘raiders’ and I nearly vanished into the strip of dark water between quay and boat. I caught myself painfully on the planks, biting my tongue as I clutched the support. ‘Raiders?’ I tasted blood and hoped it wasn’t a premonition.

Snorri shook his head. ‘Not serious stuff. The clans raid for wives come spring. Here it’ll be Guntish men.’

‘Ayuh. And Westerfolk off Crow Island.’ The old man set down his nets and came to join us, making an easier job of it than I had.

‘Lead on.’ I waved him forward, happy to trail behind if it meant him getting speared rather than me.

Now that Snorri had mentioned it I did recall talk of the practice back at the Three Axes. The business of raiding for girls of marriageable age seemed something that the people of Trond felt beneath them, but they loved to tell tales about their country bumpkin cousins doing it. Mostly it seemed to be an almost good-natured thing with a tacit approval from both sides – but of course if the raider proved sufficiently unskilled to get caught then he’d earn himself a good beating … and sometimes a bad one. And if he picked a girl that didn’t want to get caught she might give him worse than that.

Men emerged from the shadows as we walked up between the huts. Our new friend, Old Engli, put them quickly at their ease and the mood lightened. Some few recognized Snorri and many more recognized his name, leading us on amid a growing crowd. Lanterns and torches lit around us, children ran into the muddy streets, mothers and daughters eyed us from glowing doorways, the occasional girl, bolder than the rest, hanging from a window recently unboarded in the wake of winter’s retreat. One or two such caught my eye, the last of them a generously proportioned young woman with corn-coloured hair descending in thick waves and hung with small copper bells.

‘Prince Jalan—’ I managed half a bow and half an introduction before Snorri’s big fist knotted in my cloak and hauled me onwards.

‘Best behaviour, Jal,’ he hissed between his teeth while offering a wide smile left and right. ‘I know these people. Let’s try not to have to leave in a hurry this time.’

‘Yes, of course!’ I shook myself free. Or he let me go. ‘Do you think I’m some sort of wild beast? I’m always on my best behaviour!’ I stomped on behind him, straightening my collar. Damn barbarian thinking he could teach a prince of Red March manners … she did have a very pretty face though … and squeezable—

‘Jal!’

I found myself marching past the entrance into which everyone else had turned. A quick reversal and I was through the mead hall’s doorway into the smoke and noise. Mead hut I’d call it – it made Olaafheim’s hall look big. More men streamed in behind me while others found their seats around the long benches. It seemed our arrival had occasioned a general call to broach casks and fill drinking horns. We’d started the party rather than crashed in on it. And that gives you a pretty good picture of Harrowheim. A place so desolate and starved of interest that the arrival of three men in a boat is cause for celebration.

‘Jal!’ Snorri slapped the tabletop to indicate a space between him and Tuttugu. It seemed well meaning enough but something in me bridled at the gesture, ordering me to my place, somewhere he could keep an eye on me. As if he didn’t trust me. Me! A prince of Red March. Heir to the throne. Being watched over by a hauldr and a fisherman as if I might disgrace myself in a den of savages. Me, being watched over by Baraqel even though I no longer had to suffer him in my head. I sat down still smiling, but feeling brittle. I snatched up the drinking horn before me and took a deep swig. The dark and sour ale within did little to improve my mood.

As the general cacophony of disputes over seating and cries for ale settled into more distinct conversations I began to realize that everyone around me was speaking Norse. Snorri gabbled away with a lean old stick of a man, spitting out words that would break a decent person’s jaw. On my other side Tuttugu had found a kindred spirit, another ginger Norseman whose red beard spilled down over a stomach so expansive it forced him to sit far enough back from the table that reaching his ale became a problem. They too were deep in conversation in old Norse. It was starting to seem that the very first person we met was the only one among them who could speak like a man of Empire.

Back in Trond most of the northmen knew the old tongue but every one of them spoke the language of Empire and would use it over beers, at work, and in the street. Generally the city folk avoided the old tongue and its complications of dialect and regional variation, sticking instead to the language of merchants and kings. In fact the only time the good folk of Trond tended to slip into Norse was when seeking the most appropriate swear word for the situation. Insulting each other is a national sport in Norseheim and for the very best results competitors like to call on the old curses of the north, preferably raiding the stock of cruel-things-to-say-about-someone’s-mother that is to be found in the great sagas.

Out in the sticks however it proved to be a very different story – a story told exclusively in a language that seemed to require you swallow a live frog to pronounce some words and gargle half a pint of phlegm for the rest. Since my grip on Norse was limited to calling someone a shithead or telling them they had very pert breasts I scowled at the company and opted to keep my mouth shut unless of course I were pouring ale into it.

The night rolled on and whilst I was deeply glad to be out of that boat, out of the wind, and to have a floor beneath me that had the decency to stay where it had been put, I couldn’t really enjoy being crammed among two score ill-smelling Harrowheimers. I had to wonder at Engli’s tale of raiding since the whole male population seemed to have jammed themselves into the mead hall at the first excuse.

‘—Hardassa!’ Snorri’s fist punctuated the word against the table and I became aware that most of the locals were listening to him now. From the hush I guessed he must be telling the tale of our trip to the Black Fort. Hopefully he wouldn’t be mentioning Loki’s key.

To my mind the Norse vilification of Loki seemed an odd thing. Of all their heathen gods Loki was clearly the most intelligent, capable of plans and tactics that could help Asgard in its wars against the giants. And yet they spurned him. The answer of course was all around me in Harrowheim. Their daughters weren’t being wooed, or seduced, they were being taken by raiders. In the ancient tales, to which each Viking aspired, strength was the only virtue, iron the only currency that mattered. Loki with his cunning, whereby a weaker man might outdo a stronger one, was an anathema to these folk. Little wonder then if his key carried a curse for any that sought to take it by main strength.

Had Olaaf Rikeson taken it by force and drawn down Loki’s curse, only to have his vast army freeze on the Bitter Ice? Whoever had given Snorri that wound had more sense than the Dead King. Using half a ton of Fenris wolf to claim the key might seem a more certain course but such methods might also be a good way to find yourself on the wrong end of a god’s wrath.

‘Ale?’ Tuttugu started filling my drinking horn without waiting on my answer.

I pursed my lips as another thought struck me – why the hell did they call them mead halls? I’d emptied several gallons from various drinking horns, flagons, tankards … even a bucket one time … in half a dozen mead halls since coming north and never once been offered mead. The closest the Norse came to sweet was leaving the salt out of their ale. While pondering this important question I decided it time to go empty my used beer into the latrine and stood with just the hint of a stagger.

‘Still getting my land legs.’ I set a hand to Tuttugu’s shoulder for support and, once steady, set off for the door.

My lack of the local lingo didn’t prove an impediment in the hunt for the latrine – I let my nose lead me. On my return to the hall the faintest jingle of bells caught my attention. Just a brief high tinkle. The sound seemed to have come from an alley between two nearby buildings, large, log-built structures, one sporting elaborate gables … possibly a temple. With a squint I could make out a cloaked figure in the gloom. I stood, blinking, hoping to God that this wasn’t some horny but myopic clansman who was going to attempt to carry me off to a distant village even more depressing than Harrowheim.

The figure held its ground, sheltered in the narrow passage. Two slim hands emerged from dark sleeves and pushed back the hood. Bells tinkled again, and the girl from the window revealed herself, a saucy quirk to her smile that required no translation.

I cast a quick glance at the glowing rectangle of the mead hall doorway, another toward the latrines, and seeing nobody looking in my direction, I hastened across the way to join my new friend in the alley.

‘Well, hello.’ I gave her my best smile. ‘I’m Prince Jalan Kendeth of Red March, the Red Queen’s heir. But you can call me Prince Jal.’

She reached out to lay a finger across my lips before whispering something that sounded as delicious as it was incomprehensible.

‘How can I say no?’ I whispered back, setting a hand to her hip and wondering for a moment what the Norse for ‘no’ actually was.

She wriggled out from beneath my palm, bells tinkling, setting her fingers between her collarbones. ‘Yngvildr.’

‘Lovely.’ My hands pursued her while my tongue considered wrestling with her name and decided not to.

Yngvildr skipped away laughing and pointed back between the buildings, more sweet gibberish spilling from her mouth. Seeing my blank look she paused and repeated herself slowly and clearly. The trouble is of course that it doesn’t matter how slowly and how clearly you repeat gibberish. It’s possible the word ‘pert’ was in there somewhere.

High above us the moon showed its face and what light it sent down into our narrow alley caught the girl’s lines, illuminating the curve of her cheek, her brow, leaving her eyes in darkness, gleaming on her bell-strewn hair, silver across the swell of her breasts, shadows descending toward a slender waist. Suddenly it didn’t really matter what she was saying.

‘Yes,’ I said, and she led the way.

We passed between the temple and its neighbour, between huts, edged around pigsties where the hogs snored restless in their hay, and out past log stacks and empty pens to where the slope mellowed toward Harrowheim’s patch of farmland. I snatched a candle-lantern hanging outside one of the last huts. She hissed and tutted, half-smiling, half-disapproving, gesturing for me to put it back, but I declined. A tallow stub in a poorly blown glass cowl was hardly grand theft and damned if I were ending the night with a broken leg or knee-deep in a slurry pit. Wherever Yngvildr planned to get her first taste of Red March I intended to get there fit enough to give good account of myself.

So we stumbled on in our small circle of light, out across a gentle slope, the earth rutted by agriculture, holding hands now, her occasionally saying something which sounded seductive but might well have been an observation on the weather. A little more than a hundred yards out from the last of the huts a tall barn loomed up at us out of the night. I stood back and watched as Yngvildr lifted the locking bar and drew back one of the plank-built double doors set into the front of the crude log structure. She looked back over her shoulder, smiling, and walked on in, swallowed by the darkness. I considered the wisdom of the liaison for about two seconds and followed her.

The lamp’s light couldn’t reach the roof or the walls but I could see enough to know the place held hay bales and farm implements. Not many of either, but plenty to trip over. Yngvildr tried once more to make me abandon the lamp, pointing to the doorway, but I smiled and pulled her close, kissing the arguments off her lips. In the end she rolled her eyes and broke free to close the door once more.