Полная версия

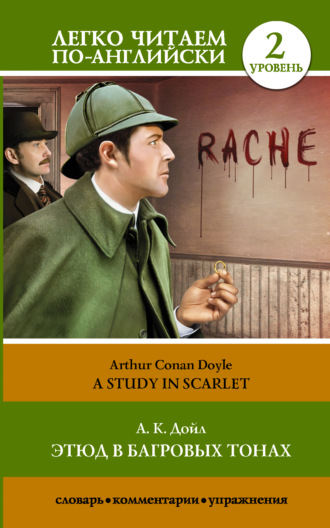

Этюд в багровых тонах / A Study in Scarlet

“John Rance,” said Lestrade. “You will find him at 46, Audley Court, Kennington Park Gate.”

“Come along, Doctor,” said Holmes; “we shall go to him. I’ll tell you one thing which may help you in the case,” he turned to the two detectives. “It was a murder, and the murderer was a man. He was more than six feet high, was in the prime of life[33], had small feet for his height, wore coarse, square-toed boots[34] and smoked a cigar. He came here with his victim in a four-wheeled cab, which was drawn by a horse with three old shoes and one new one on his off fore leg[35]. The murderer had a florid face, and the finger-nails of his right hand were remarkably long. These indications may assist you.”

Lestrade and Gregson glanced at each other with an incredulous smile.

“How was this man murdered?” asked they.

“Poison,” said Sherlock Holmes curtly. “One other thing, Lestrade,” he added: “‘Rache,’ is the German for ‘revenge;’ so don’t look for Miss Rachel.”

Chapter IV

What John Rance Had to Tell

It was one o’clock when we left No. 3, Lauriston Gardens. Sherlock Holmes led me to the nearest telegraph office, whence he dispatched a long telegram. He then hailed a cab, and ordered the driver to take us to the address which Lestrade gave us.

“You amaze me, Holmes,” said I. “How do you know all those particulars of the case?”

“Look,” he answered. “the first thing: a cab made two ruts with its wheels close to the curb. Now, up to last night, we had no rain. So those wheels – which left such a deep impression – were there during the night. There were the marks of the horse’s hoofs, too, the outline of one hoof was very clear. This was a new shoe. Since the cab was there after the rain began, and was not there at any time during the morning, it was there during the night, and, therefore, it brought those two men to the house.”

“But how did you know the man’s height?” said I.

“The height of a man is connected to the length of his stride. It is a simple calculation. I had this fellow’s stride both on the clay outside and on the dust within. Moreover: when a man writes on a wall, he usually writes about the level of his own eyes. That writing was just over six feet from the ground.”

“And his age?” I asked.

“Well, if a man can stride four and a half feet without the effort, he is strong enough. That was the breadth of a puddle on the garden walk which he jumped over. There is no mystery about it at all. I am simply applying to ordinary life some deduction. Is there anything else that puzzles you?”

“The finger nails and the cigar,” I suggested.

“The writing on the wall was done with a man’s forefinger dipped in blood. The plaster was scratched. This is impossible if the man’s nail is trimmed. I gathered up some ash from the floor.

It was dark in colour and flakey – a cigar, for sure. I made a special study of cigar ashes – in fact, I wrote a monograph upon the subject.”

“And the florid face?” I asked.

“Ah, please don’t ask about it now, though I have no doubt that I was right.”

“But, Holmes,” I remarked; “why did these two men – if there were two men – come into an empty house? How did the victim take poison? Where did the blood come from? What was the object of the murderer? What about the woman’s ring there? Why did the second man write the German word RACHE?”

My companion smiled approvingly.

“My dear Watson,” Holmes said, “many things are still obscure. About Lestrade’s discovery. Not a German man wrote it. The letter A, if you noticed, was printed after the German fashion[36]. But a real German invariably prints in the Latin character[37]. So we may say that a clumsy imitator wrote that. I’ll tell you more. Both men came in the same cab, and they walked down the pathway together. When they got inside they walked up and down the room. I could read all that in the dust. Then the tragedy occurred.”

Our cab was going through a long succession of dingy streets and dreary by-ways. In the dingiest and dreariest of them our driver suddenly stopped.

“That’s Audley Court in there,” he said. “You’ll find me here when you come back.”

We came to Number 46, and saw a small slip of brass on which the name Rance was engraved. The constable appeared.

“I made my report at the office,” he said.

Holmes took a half-sovereign from his pocket.

“We want to hear it all from your own lips,” he said.

“I shall be most happy to tell you anything I can,” the constable answered.

“How did it occur?”

Rance sat down on the sofa, and knitted his brows.

“I’ll tell it from the beginning,” he said. “My time is from ten at night to six in the morning. At one o’clock it began to rain, and I met Harry Murcher and we stood together and talked a little. After that – maybe about two or a little after – I decided to take a look round. The road was dirty and lonely. I met nobody all the way down, though a cab or two went past me. Suddenly I saw a light in the window of that house. When I came to the door…”

“You stopped, and then walked back to the garden gate,” my companion interrupted. “Why did you do that?”

Rance stared at Sherlock Holmes with the utmost amazement.

“Yes, that’s true, sir,” he said; “but how do you know it? When I got up to the door it was so still and so lonesome, that I decided to take somebody with me, maybe Murcher. And I walked back. But I saw no one.”

“There was no one in the street?”

“Not a soul, sir. Then I went back and opened the door. All was quiet inside, so I went into the room where the light was burning. There was a candle on the mantelpiece – a red wax one – and I saw…”

“Yes, I know all that you saw. You walked round the room several times, and you knelt down by the body, and then you walked through and opened the kitchen door, and then…”

John Rance sprang to his feet with a frightened face.

“Where were you, sir, that time? You saw all that!” he cried. “It seems to me that you know too much.”

Holmes laughed and threw his card across the table to the constable.

“Don’t arrest me for the murder,” he said. “I am one of the hounds; Mr. Gregson or Mr. Lestrade can say that as well. Go on, though. What did you do next?”

“I went back to the gate and sounded my whistle. Murcher and two more arrived.”

“Was the street empty then?”

“Only a drunker. I saw many drunkers in my life,” he said, “but not like that one. He was at the gate when I came out, he was leaning up against the railings, and singing a song. He couldn’t stand at all.”

“What sort of a man was he?” asked Sherlock Holmes. “His face – his dress – didn’t you notice them?”

“He was a long chap, with a red face, the lower part muffled round[38]…”

“What became of him?” cried Holmes.

“I think he found his way home,” the policeman said.

“How was he dressed?”

“A brown overcoat.”

“Had he a whip in his hand?”

“A whip – no.”

“Did you see or hear a cab?” asked Holmes.

“No.”

“There’s a half-sovereign for you,” my companion said. “I am afraid, Rance, that you will never became a sergeant. That man is the man who holds the clue of this mystery, and whom we are seeking. Come along, Doctor.”

“The fool,” Holmes said, bitterly, as we drove back to our lodgings.

“Holmes, it is true that the description of this man tallies with your idea of the second person in this mystery. But why did the criminal come back to the house again?”

“The ring, the ring. We will use that ring, Doctor, to catch him. I must thank you for this case. I was lazy enough to go, but you forced me! A study in scarlet, eh? Let’s use a little art jargon. There’s the scarlet thread of murder through the colourless skein of life, and our duty is to unravel it, and isolate it.”

Chapter V

Our Advertisement Brings a Visitor

I lay down upon the sofa and tried to sleep. But every time that I closed my eyes I saw before me the distorted baboon-like countenance of the murdered man.

Was that man poisoned? Holmes sniffed his lips, and probably detected something. And if not poison, what caused the man’s death? There was neither wound nor marks of strangulation. But, on the other hand, whose blood was there upon the floor? We saw no signs of a struggle, the victim did not have any weapon. My friend’s quiet self-confident manner convinced me that he had a theory which explained all the facts.

Holmes came very late. Dinner was on the table before he appeared.

“What’s the matter?” he answered. “Does this Brixton Road affair trouble you?”

“To tell the truth, it does,” I said.

“I can understand. There is a mystery about this which stimulates the imagination. Did you see the evening paper?”

“No.”

“It tells about the affair. And it does not mention the woman’s wedding ring. That’s good.”

“Why?”

“Look at this advertisement,” he answered. “I sent it to every paper in the morning immediately after the affair.”

He gave me the newspaper.

“In Brixton Road, this morning,” it ran, “a plain gold wedding ring, found in the roadway between the ‘White Hart’ Tavern and Holland Grove. Apply Dr. Watson, 221B, Baker Street, between eight and nine this evening.”

“Excuse me. I used your name,” he said.

“That is all right,” I answered. “But I have no ring.”

“Oh yes, you have,” said he. And he gave me one. “This will do very well[39].”

“And who will answer this advertisement?”

“The man in the brown coat – our florid friend with the square toes. If he does not come himself he will send an accomplice.”

“Isn’t that dangerous for him?”

“Not at all. I think that this man will rather risk anything than lose the ring. He dropped it when he stooped over Drebber’s body. Then he left the house. He discovered his loss and hurried back, but found the police because the candle was burning. He pretended to be drunk in order to allay the suspicions. Now put yourself in that man’s place. He thinks that he lost the ring in the road. What will he do, then? He will eagerly read the evening papers. And he will read this advertisement. He will be overjoyed. Why fear? He will come. You will see him within an hour.”

“And then?” I asked.

“Oh, I’ll talk to him. Have you any arms?”

“I have my old revolver and a few cartridges.”

“Clean it and load it. We must be ready for anything.”

I went to my bedroom and followed his advice. When I returned with the pistol, Holmes was playing violin.

“I have an answer to my American telegram,” he said, as I entered.

“And?” I asked eagerly.

“Put your pistol in your pocket,” he remarked. “When the fellow comes speak to him in an ordinary way. Leave the rest to me. Don’t frighten him.”

“It is eight o’clock now,” I said.

“Yes. He will probably be here in a few minutes. Open the door slightly. Now put the key on the inside[40]. Thank you. Here comes our man, I think.”

As he spoke there was a sharp ring at the bell. Sherlock Holmes rose softly and moved his chair in the direction of the door.

“Does Dr. Watson live here?” asked a clear but rather harsh voice. We could not hear the servant’s reply, but the door closed, and some one began to ascend the stairs. There was a feeble tap at the door.

“Come in,” I cried.

Instead of the man whom we expected, a very old and wrinkled woman hobbled into the apartment. She was blinking at us with her bleared eyes and fumbling in her pocket with nervous, shaky fingers.

The old crone drew out an evening paper, and pointed at our advertisement.

“A gold wedding ring in the Brixton Road, gentlemen,” she said; “It belongs to my daughter Sally. She went to the circus yesterday and lost it.”

“Is that her ring?” I asked.

“Yes!” cried the old woman; “Sally will be very glad. That’s the ring.”

“And what is your address?” I inquired.

“13, Duncan Street, Houndsditch. A long way from here.”

“The Brixton Road does not lie between any circus and Houndsditch,” said Sherlock Holmes sharply.

The old woman looked keenly at him.

“The gentleman asked me for my address,” she said. “Sally lives in lodgings at 3, Mayfield Place, Peckham.”

“And your name is…?”

“My name is Sawyer – hers is Dennis. Tom Dennis married her, a smart lad…”

“Here is your ring, Mrs. Sawyer,” I interrupted; “it clearly belongs to your daughter, and I am glad to restore it to the rightful owner.”

With many words of gratitude the old crone took the ring and went down the stairs. Sherlock

Holmes sprang to his feet and rushed into his room. He returned in a few seconds.

“I’ll follow her,” he said, hurriedly; “she must be an accomplice, and will lead me to him. Wait here.”

And Holmes descended the stair. It was nine when he left. Ten o’clock passed, eleven, he did not come back. It was about twelve when I heard the sharp sound of his key. When he entered, he laughed.

“So what?” I asked.

“That woman went a little when she began to limp. Then she hailed a cab. I was close to her so I heard the address, she cried loud enough, ‘Drive to 13, Duncan Street, Houndsditch.’ When she was inside, I perched myself behind. Well, we reached the street. I hopped off before we came to the door. The driver jumped down. He opened the door and stood expectantly. Nobody came out. There was no sign or trace of his passenger. At Number 13 a respectable paperhanger lives, he never heard about Sawyer or Dennis.”

“You want to say,” I cried, in amazement, “that that feeble old woman was able to get out of the cab while it was in motion?”

“Old woman!” said Sherlock Holmes, sharply. “We were the old women ourselves. It was a young man, an incomparable actor. It shows that the criminal has friends who are ready to risk something for him.”

Chapter VI

Tobias Gregson Shows What He Can Do

The papers next day were full of the “Brixton Mystery,” as they termed it. There was some information in them which was new to me.

The Daily Telegraph mentioned the German name of the victim, the absence of all other motive, and the sinister inscription on the wall; all that pointed to political refugees and revolutionists. The Standard said that the victim was an American gentleman who was staying in Camberwell.

He has his private secretary, Mr. Joseph Stangerson. They left their landlady upon Tuesday, the 4th., and departed to Euston Station to catch the Liverpool express. Then Mr. Drebber’s body was discovered in an empty house in the Brixton Road, many miles from Euston. How he came there, or how he met his fate, are questions. Where is Stangerson? Nobody knows. We are glad to know that Mr. Lestrade and Mr. Gregson, of Scotland Yard, are both engaged upon the case, and they will soon throw light upon the matter.

The Daily News said that it was a political murder.

Sherlock Holmes and I read these articles at breakfast.

“What is this?” I cried, for at this moment there came the pattering of many steps in the hall and on the stairs.

“It’s the Baker Street detective police,” said my companion, gravely. As he spoke there rushed into the room half a dozen of dirty street boys.

“Hush!” cried Holmes, in a sharp tone. “In future you will send Wiggins alone to report. Any news, Wiggins?”

“No, sir,” said one of the youths.

“I knew that. Here are your wages.” He handed each of them a shilling. “Now go away and come back with a better report next time.”

They scampered away downstairs like rats.

“One of those little beggars is better than a dozen of the policemen,” Holmes remarked. “These youngsters go everywhere and hear everything.”

“Are you employing them for this Brixton case?” I asked.

“Yes. It is merely a matter of time. Oh! Here is Gregson coming down the road. He wants to visit us, I know. Yes, he is stopping. There he is!”

There was a violent peal at the bell, and in a few seconds the fair-haired detective came up the stairs.

“My dear fellow,” he cried, “congratulate me! I solved the problem.”

“Do you mean that you know the criminal?” asked Holmes.

“Sir, we have the man under lock and key!”

“And his name is?”

“Arthur Charpentier, sub-lieutenant in Her Majesty’s navy[41],” cried Gregson, pompously.

Sherlock Holmes smiled.

“Take a seat,” he said. “And please tell us everything.”

The detective seated himself in the arm-chair. Then suddenly he slapped his thigh.

“The fun of it is,” he cried, “that that fool Lestrade, who thinks himself so smart, went the wrong way. He suspects the secretary Stangerson, who has nothing with the crime.”

Gregson laughed.

“And how did you get your clue?” I asked.

“Ah, I’ll tell you all about it. Of course, Doctor Watson, this is strictly between ourselves. The first difficulty was to finding the information about the victim’s American life. Do you remember the hat beside the dead man?”

“Yes,” said Holmes; “by John Underwood and Sons, 129, Camberwell Road.”

“I had no idea that you noticed that,” said Gregson. “Well, I went to Underwood, and asked him about the customer of that hat. He looked over his books, and found him. He sent the hat to a Mr. Drebber, residing at Charpentier’s Boarding Establishment, Torquay Terrace[42]. Thus I got at his address.”

“Smart – very smart!” murmured Sherlock Holmes.

“Then I met Madame Charpentier,” continued the detective. “I found her very pale and distressed. Her daughter was in the room, too. Her lips trembled as I spoke to her. That didn’t escape my notice. I began to smell a rat. You know the feeling, Mr. Sherlock Holmes – a kind of thrill in your nerves. ‘Do you know about the mysterious death of your boarder Mr. Enoch J. Drebber, of Cleveland?’ I asked.

The mother nodded. The daughter burst into tears[43]. ‘At what o’clock did Mr. Drebber leave your house for the train?’ I asked.

‘At eight o’clock,’ she said. ‘His secretary, Mr. Stangerson, said that there were two trains – one at 9.15 and one at 11. He wanted to catch the first.

‘And did you see him after that?’

A terrible change came over the woman’s face as I asked the question.

‘No,’ she said in a husky unnatural tone.

There was silence for a moment, and then the daughter spoke in a calm voice.

‘Please, don’t lie, mother,’ she said. ‘Let us be frank with this gentleman. We saw Mr. Drebber again.’

‘Oh!’ cried Madame Charpentier. ‘You murdered your brother!’

‘Please tell me all about it now,’ I said.

‘I will tell you all, sir!’ cried her mother, ‘Alice, leave us together. Now, sir,’ she continued, ‘I have no alternative. Mr. Drebber stayed with us nearly three weeks. He and his secretary, Mr. Stangerson, were travelling on the Continent. I noticed a “Copenhagen” label upon each of their trunks. Stangerson was a quiet reserved man, but his employer, I am sorry to say, was coarse and brutish. He drank a lot, and, indeed, after twelve o’clock he was never sober. His manners towards the maid-servants were disgustingly free and familiar. Worst of all, he assumed the same attitude towards my daughter, Alice. Once he seized her in his arms and embraced her, his own secretary reproached him for his unmanly conduct.’

‘But why did you stand all this?’ I asked.

Mrs. Charpentier blushed.

‘Money, sir,’ she said. ‘They were paying a pound a day each – fourteen pounds a week. I am a widow, and my boy in the Navy cost me much. But finally I gave Mr. Drebber’s notice to leave.’

‘Well?’

‘So he drove away. I did not tell my son anything of all this, for his temper is violent. When I closed the door behind them I felt happy. Alas, in less than an hour there was a ring at the bell. Mr. Drebber returned. He was much excited and drunk. He came way into the room, where I was sitting with my daughter. He missed his train. He then turned to Alice, and offered her to go with him. “You are big enough,” he said, “and there is no law to stop you. I have money enough and to spare. Come with me! You will live like a princess.” Poor Alice was so frightened that she shrunk away from him, but he caught her by the wrist. I screamed, and at that moment my son Arthur came into the room.

What happened then I do not know. I was too terrified to raise my head. When I looked up I saw Arthur in the doorway. He was laughing, with a stick in his hand.

“I don’t think that fellow will trouble us again,” he said. “I will go and see what he is doing at the moment.”

With those words he took his hat and went out. The next morning we heard of Mr. Drebber’s mysterious death.’

This statement came from Mrs. Charpentier’s lips with many gasps and pauses.”

“It’s very interesting,” said Sherlock Holmes, with a yawn. “What happened next?”

“When Mrs. Charpentier paused,” the detective continued, “I asked her at what hour her son returned.

‘I do not know,’ she answered. He has a key.’

‘When did you go to bed?’

‘About eleven.’

‘So your son was away at least two hours?’

‘Yes.’

‘Possibly four or five?’

‘Yes.’

‘What was he doing during that time?’

‘I do not know,’ she answered.

Of course after that I found out where Lieutenant Charpentier was, took two officers with me, and arrested him. When I touched him on the shoulder and offered him to come quietly with us, he said, ‘I suppose you are arresting me for the death of that scoundrel Drebber,’ he said. We said nothing to him about it, so this is very suspicious.”

“Very,” said Holmes.

“He still carried the heavy stick. It was a stout oak cudgel.”

“What is your theory, then?”

“Well, my theory is that he followed Drebber as far as the Brixton Road. There they had a fight, in the course of which Drebber received a blow from the stick, in the pit of the stomach, perhaps, which killed him without any mark. Then Charpentier dragged the body of his victim into the empty house. As to the candle, and the blood, and the writing on the wall, and the ring, they are just tricks to deceive the police.”

“Well done, Gregson!” said Holmes.

“Yes,” the detective answered proudly. “The young man says that Drebber perceived him, and took a cab in order to get away from him. On his way home he met an old shipmate[44], and took a long walk with him. I asked him where this old shipmate lived, but he was unable to give any satisfactory reply. But Lestrade! Just think of him! He knows nothing at all. Oh, here’s Lestrade himself!”

It was indeed Lestrade, who had ascended the stairs while we were talking, and who now entered the room. His face was disturbed and troubled, while his clothes were disarranged and untidy. He stood in the centre of the room. He was fumbling nervously with his hat.

“This is a most extraordinary case,” he said at last, “a most incomprehensible affair.”

“You think so, Mr. Lestrade!” cried Gregson, triumphantly. “Did you find the Secretary, Mr. Joseph Stangerson?”

“The Secretary, Mr. Joseph Stangerson,” said Lestrade gravely, “was murdered at Halliday’s Private Hotel about six o’clock this morning.”

Chapter VII

Light in the Darkness

This news was unexpected. Gregson sprang out of his chair. I stared in silence at Sherlock Holmes, whose lips were compressed.

“Stangerson too!” he muttered.

Lestrade took a chair.

“Are you sure of this?” stammered Gregson.

“I was in his room,” said Lestrade. “I was the first to discover that.”

“Please, Mr. Lestrade, let us know what you saw,” Holmes observed.

“You see,” Lestrade answered, “I thought that Stangerson was concerned in the death of Drebber. I was wrong, it’s true. Anyway, I wanted to find the Secretary. They were together at Euston Station about half-past eight on the evening. At two in the morning Drebber was found in the Brixton Road. The question is: what did Stangerson do between 8.30 and the time of the crime, and what did he do afterwards. I telegraphed to Liverpool. I gave a description of the man, and asked them to watch upon the American boats. I then called upon all the hotels in the vicinity of Euston. You see, if Drebber and his companion become separated, Stangerson stayed somewhere in the vicinity for the night, and then went to the station again next morning.”