Полная версия

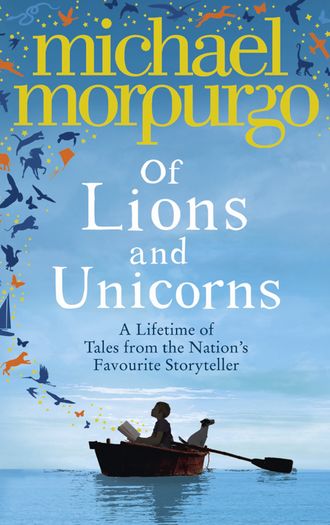

Of Lions and Unicorns: A Lifetime of Tales from the Master Storyteller

I could have given it to your Auntie Mary for her to give to you, but I don’t want her to know I’m doing this – I don’t like to upset her. And anyway, as you’ll soon discover, this is between you and me. Your Auntie Mary knows the truth of everything that’s written here – she was so much part of the whole story – but she’s always told me it was best to keep it as a secret between her and me, just the two of us, and so it always has been. That way, she thinks, no one comes to any harm.

Until just recently, until my last visit to the hospital, when they told me, I suppose I always used to believe she was right. But not any more. I think there are some things that are so much part of who we are, that we should know about them, that we have a right to know about them.

If you’re reading this at all, Michael, then it means you’ve found my little writing pad behind the photo of your Papa, just as I intended you to. Please don’t be too upset. Read it again from time to time as you get older. I think it will be easier to understand as you get older. It’s not so much that wisdom comes with age – as we older people rather like to believe. It doesn’t. But I am sure that as we grow up we do become more able to understand ourselves and other people a little better. We are more able to deal with difficulty, and to forgive perhaps. If you are anything like me, Michael – and I think you probably are – I am sure you will become more understanding and forgiving as the years pass. I hope so, because I’m sure that it’s only in forgiving that we find real peace of mind.

I’m writing this as well, because I want you to feel proud of who you are, and proud of the people who made you. Believe you me, you have much to feel proud about. Perhaps my problem has always been that I have never been proud enough of who I am. I am a bit muddle-headed, simple-minded perhaps, and foolish, certainly foolish. I have always allowed my sister, whom I love dearly, to do most of my thinking for me. It’s just how we are and always have been. She’s been the strong one all my life, my rock you might say. I know she can seem a bit of a know-all, a bit overbearing; but as you’ll soon discover, she has looked after me, stood by me when no one else would. There’s a lot more to Mary than meets the eye – that’s true of everyone, I think. I should have been quite lost in this life without her. So here’s our story, hers and mine – and most importantly, yours.

In 1943, Lily Tregenza was living in a sleepy seaside village, scarcely touched by the war. But all that was soon to change. This is how I began to learn of her story …

Ever since I could remember I’d been coming down to Slapton for my holidays, mostly on my own. Grandma’s bungalow was more of a home to me than anywhere, because we’d moved house often – too often for my liking. I’d just get used to things, settle down, make a new set of friends and then we’d be off, on the move again. Slapton summers with Grandma were regular and reliable and I loved the sameness of them, and Harley in particular.

Grandma used to take me out in secret on Grandpa’s beloved motorbike, his pride and joy, an old Harley-Davidson. We called it Harley. Before Grandpa became ill they would go out on Harley whenever they could, which wasn’t often. She told me once those were the happiest times they’d had together. Now that he was too ill to take her out on Harley, she’d take me instead. We’d tell Grandpa all about it, of course, and he liked to hear exactly where we’d been, what field we’d stopped in for our picnic and how fast we’d gone. I’d relive it for him and he loved that. But we never told my family. It was to be our secret, Grandma said, because if anyone back home ever got to know she took me out on Harley they’d never let me come to stay again. She was right too. I had the impression that neither my father (her own son) nor my mother really saw eye to eye with Grandma. They always thought she was a bit stubborn, eccentric, irresponsible even. They’d be sure to think that my going out on Harley with her was far too dangerous. But it wasn’t. I never felt unsafe on Harley, no matter how fast we went. The faster the better. When we got back, breathless with excitement, our faces numb from the wind, she’d always say the same thing: “Supreme, Boowie! Wasn’t that just supreme?”

When we weren’t out on Harley, we’d go on long walks down to the beach and fly kites, and on the way back we’d watch the moorhens and coots and herons on Slapton Ley. We saw a bittern once. “Isn’t that supreme?” Grandma whispered in my ear. Supreme was always her favourite word for anything she loved: for motorbikes or birds or lavender. The house always smelt of lavender. Grandma adored the smell of it, the colour of it. Her soap was always lavender, and there was a sachet in every wardrobe and chest of drawers – to keep moths away, she said.

Best of all, even better than clinging on to Grandma as we whizzed down the deep lanes on Harley, were the wild and windy days when the two of us would stomp noisily along the pebble beach of Slapton Sands, clutching on to one another so we didn’t get blown away. We could never be gone for long though, because of Grandpa. He was happy enough to be left on his own for a while, but only if there was sport on the television. So we would generally go off for our ride on Harley or on one of our walks when there was a cricket match on, or rugby. He liked rugby best. He had been good at it himself when he was younger, very good, Grandma said proudly. He’d even played for Devon from time to time – whenever he could get away from the farm, that is.

Grandma told me a little about the busy life they’d had before I was born, up on the farm – she’d taken me up there to show me. So I knew how they’d milked a herd of sixty South Devon cows and that Grandpa had gone on working as long as he could. In the end, his illness took hold and he couldn’t go up and down stairs any more, they’d had to sell up the farm and the animals and move into the bungalow down in Slapton village. Mostly, though, she’d want to talk about me, ask about me, and she really wanted to know too. Maybe it was because I was her only grandson. She never seemed to judge me either. So there was nothing I didn’t tell her about my life at home or my friends or my worries. She never gave advice, she just listened.

Once, I remember, she told me that whenever I came to stay it made her feel younger. “The older I get,” she said, “the more I want to be young. That’s why I love going out on Harley. And I’m going to go on being young till I drop, no matter what.”

I understood well enough what she meant by “no matter what”. Each time I’d gone down in the last couple of years before Grandpa died she had looked more grey and weary. I would often hear my father pleading with her to have Grandpa put into a nursing home, that she couldn’t go on looking after him on her own any longer. Sometimes the pleading sounded more like bullying to me, and I wished he’d stop. Anyway, Grandma wouldn’t hear of it. She did have a nurse who came in to bath Grandpa each day now, but Grandma had to do the rest all by herself, and she was becoming exhausted. More and more of my walks along the beach were alone nowadays. We couldn’t go out on Harley at all. She couldn’t leave Grandpa even for ten minutes without him fretting, without her worrying about him. But after Grandpa was in bed we would either play Scrabble, which she would let me win sometimes, or we’d talk on late into the night – or rather I would talk and she would listen. Over the years I reckon I must have given Grandma a running commentary on just about my entire life, from the first moment I could speak, all the way through my childhood.

But now, after Grandpa’s funeral, as we walked together down the road to the pub with everyone following behind us, it was her turn to do the talking, and she was talking about herself, talking nineteen to the dozen, as she’d never talked before. Suddenly I was the listener.

The wake in the pub was crowded, and of course everyone wanted to speak to Grandma, so we didn’t get a chance to talk again that day, not alone. I was playing waiter with the tea and coffee, and plates of quiches and cakes. When we left for home that evening Grandma hugged me especially tight, and afterwards she touched my cheek as she’d always done when she was saying goodnight to me before she switched off the light. She wasn’t crying, not quite. She whispered to me as she held me. “Don’t you worry about me, Boowie dear,” she said. “There’s times it’s good to be on your own. I’ll go for rides on Harley – Harley will help me feel better. I’ll be fine.” So we drove away and left her with the silence of her empty house all around her.

A few weeks later she came to us for Christmas, but she seemed very distant, almost as if she were lost inside herself: there, but not there somehow. I thought she must still be grieving and I knew that was private, so I left her alone and we didn’t talk much. Yet, strangely, she didn’t seem too sad. In fact she looked serene, very calm and still, a dreamy smile on her face, as if she was happy enough to be there, just so long as she didn’t have to join in too much. I’d often find her sitting and gazing into space, remembering a Christmas with Grandpa perhaps, I thought, or maybe a Christmas down on the farm when she was growing up.

On Christmas Day itself, after lunch, she said she wanted to go for a walk. So we went off to the park, just the two of us. We were sitting watching the ducks on the pond when she told me. “I’m going away, Boowie,” she said. “It’ll be in the New Year, just for a while.”

“Where to?” I asked her.

“I’ll tell you when I get there,” she replied. “Promise. I’ll send you a letter.”

She wouldn’t tell me any more no matter how much I badgered her. We took her to the station a couple of days later and waved her off. Then there was silence. No letter, no postcard, no phone call. A week went by. A fortnight. No one else seemed to be that concerned about her, but I was. We all knew she’d gone travelling, she’d made no secret of it, although she’d told no one where she was going. But she had promised to write to me and nothing had come. Grandma never broke her promises. Never. Something had gone wrong, I was sure of it.

Then one Saturday morning I picked up the post from the front door mat. There was one for me. I recognised her handwriting at once. The envelope was quite heavy too. Everyone else was soon busy reading their own post, but I wanted to open Grandma’s envelope in private. So I ran upstairs to my room, sat on my bed and opened it. I pulled out what looked more like a manuscript than a letter, about thirty or forty pages long at least, closely typed. On the cover page she had sellotaped a black and white photograph (more brown and white really) of a small girl who looked a lot like me, smiling toothily into the camera and cradling a large black and white cat in her arms. There was a title: The Amazing Story of Adolphus Tips, with her name underneath, Lily Tregenza. Attached to the manuscript by a large multi-coloured paperclip was this letter.

Dearest Boowie,

This is the only way I could think of to explain to you properly why I’ve done what I’ve done. I’ll have told you some of this already over the years, but now I want you to know the whole story. Some people will think I’m mad, perhaps most people – I don’t mind that. But you won’t think I’m mad, not when you’ve read this. You’ll understand, I know you will. That’s why I particularly wanted you to read it first. You can show it to everyone else afterwards. I’ll phone soon … when you’re over the surprise.

When I was about your age – and by the way that’s me on the front cover with Tips – I used to keep a diary. I was an only child, so I’d talk to myself in my diary. It was company for me, almost like a friend. So what you’ll be reading is the story of my life as it happened, beginning in the autumn of 1943, during the Second World War, when I was growing up on the family farm. I’ll be honest with you, I’ve done quite a lot of editing. I’ve left bits out here and there because some of it was too private or too boring or too long. I used to write pages and pages sometimes, just talking to myself, rambling on.

The surprise comes right at the very end. So don’t cheat, Boowie. Don’t look at the end. Let it be a surprise for you – as it still is for me.

Lots of love,

Grandma

PS Harley must be feeling very lonely all on his own in the garage. We’ll go for a ride as soon as I get back; as soon as you come to visit. Promise.

Billy the Kid was Chelsea football club’s champion striker, but that was before war broke out. His love of the beautiful game sees Billy through the lowest of times, when he is made a prisoner of war …

Once the letters came I felt much better, for a while. Lots of them came at once – we never knew why. But it was good just to hear that Mum and Ossie and Emmy were all right, that they were still there, and I wasn’t alone in the world. There’d been some bombing in London, so they’d sent Emmy down to Aunty Mary’s in Broadstairs for a while. She sounded very different in her letter, very grown up somehow. She told me how she wanted to go back home, but that Mum wouldn’t let her, how Aunty Mary fussed over her and how she was fed up with her. She told me she had decided she was going to be a nurse when she was older. I read the letters over and over again, and wrote home whenever I could. Those letters were my lifeline. The next best thing in the world were the Red Cross parcels. How I looked forward to them – marmalade, chocolate, biscuits, cigarettes. We did a lot of swapping and bartering after they came. I’d swap my cigarettes for Robbie’s chocolate – never did like smoking, just not my vice – I did my best to end up with mostly chocolate. It lasted longer, if I didn’t get too greedy.

As for the Italians guarding us – there were two sorts. You had the kind ones, and that was most of them, who’d pass the time of day, have a joke with you; and then the others, the nasty ones, the real fascists who strutted about the place like peacocks and treated us like dirt. But what really got me down was the boredom, the sameness of every day. I had so much time to think and it was thinking that always dragged me down, and then I wouldn’t feel like doing anything. I wouldn’t even kick a football about.

It was partly to perk me up, I reckon, that Robbie came up with the idea of an FA Cup competition. He organised the whole thing. Soon we had a dozen league sides – all mad keen supporters only too willing to turn out for ‘their’ club back home. I trained the Chelsea team, and played centre forward. Robbie was at left back, solid as a rock. For weeks on end the camp was a buzz of excitement. Everyone trained like crazy. Suddenly we all had something to do, something to work for. What some of us might have been lacking in skill and fitness, we made up for in enthusiasm. The Italians laughed at us a bit to start with, but as we all got better they began to take a real interest in it. In the end they even volunteered to provide the referees.

I was a marked man of course, but I was used to that. I got up to all my old tricks, and the crowd loved it. Robbie was thunderous in his tackling. Chelsea got through the final, against Newcastle.

So in April 1943, under Italian sunshine and behind the barbed wire, we had our very own FA Cup Final. The whole camp was there to watch, over two thousand men, and hundreds of Italians too, including the Commandatore himself. It was quite a match. They were all over us to start with, and had me marked so close I could hardly move. Paulo – one of the Italian guards we all liked – turned out to be a lousy ref, or maybe he was a secret Newcastle supporter, because every decision went against us. At half time we were a goal down. Luckily they ran out of puff in the second half and I squeezed in a couple of cheeky goals. Half the crowd went wild when I scored the winner, and when it was all over someone started singing ‘Abide With Me’. We fairly belted it out, and when we’d finished we all clapped and cheered, and to be fair, the Italians did too. They were all right – most of them.

Next day came the big surprise. Paulo came up to me as I was sitting outside the hut writing a letter. “Before the war I see England play against Italia in Roma,” he said. “Why we not play Italia against England, here, in this camp?”

So there we were a couple of weeks later on the camp football field facing each other, the best of us against the best of them. We all had white shirts and they had blue – like the real thing. Paulo captained them, I captained us. They were good too, tricky and quick. They ran circles round us. I found myself defending with the back four, marshalling the middle and trying to score goals all at the same time. It didn’t work. They went one goal up soon after half time and were well on top too for most of the second half. We really had our backs to the wall. The crowd had all gone very quiet. We were all bunched – when the ball landed at my feet. I was exhausted. All I wanted to do was boot it up the field, just to get it clear. But I had four Italians coming at me and that fired me up. I beat one and another, then another, and leaving Paulo sprawling, made for their goal. I had just the goalie to beat. I feinted this way, that way and stroked it in. It was the best goal I ever scored. The whistle blew for full time. I was hoisted up and carried in triumph round the camp. We hadn’t won, but we hadn’t lost. Honours even. Just as well, I’ve always thought. Both sides could laugh about it afterwards. Important that.

Michael remembers his childhood visits to Great Aunt Laura on the Scilly Isles. He always loved the stories she would tell. As a parting gift, Great Aunt Laura leaves him the most special story of all …

I took the boat across to Scilly for the funeral – almost everyone in the family did. I met again cousins and aunts and uncles I hardly recognised, and who hardly recognised me. The little church on Bryher was packed, standing room only. Everyone on Bryher was there, and they came from all over the Scilly Isles, from St Mary’s, St Martin’s, St Agnes and Tresco.

We sang the hymns lustily because we knew Great-aunt Laura would enjoy a rousing send-off. Afterwards we had a family gathering in her tiny cottage overlooking Stinking Porth Bay. There was tea and crusty brown bread and honey. I took one mouthful and I was a child again. Wanting to be on my own, I went up the narrow stairs to the room that had been mine when I came every summer for my holidays. The same oil lamp was by the bed, the same peeling wallpaper, the same faded curtains with the red sailing boats dipping through the waves.

I sat down on the bed and closed my eyes. I was eight years old again and ahead of me were two weeks of sand and sea and boats and shrimping, and oystercatchers and gannets, and Great-aunt Laura’s stories every night before she drew the curtains against the moon and left me alone in my bed.

Someone called from downstairs and I was back to now.

Everyone was crowded into her sitting room. There was a cardboard box open in the middle of the floor.

“Ah, there you are, Michael,” said Uncle Will. He was a little irritated, I thought.

“We’ll begin then.”

And a hush fell around the room. He dipped into the box and held up a parcel.

“It looks as if she’s left us one each,” said Uncle Will. Every parcel was wrapped in old newspaper and tied with string, and there was a large brown label attached to each one. Uncle Will read out the names. I had to wait some minutes for mine. There was nothing I particularly wanted, except Zanzibar of course, but then everyone wanted Zanzibar. Uncle Will was waving a parcel at me.

“Michael,” he said, “here’s yours.”

I took it upstairs and unwrapped it sitting on the bed. It felt like a book of some sort, and so it was, but not a printed book. It was handmade, handwritten in pencil, the pages sewn together. The title on the cover read The Diary of Laura Perryman and there was a watercolour painting on the cover of a four-masted ship keeling over in a storm and heading for the rocks. With the book there was an envelope.

I opened it and read.

Dear Michael

When you were little I told you lots and lots of stories about Bryher, about the Isles of Scilly. You know about the ghosts on Samson, about the bell that rings under the sea off St Martin’s, about King Arthur still waiting in his cave under the Eastern Isles.

You remember? Well, here is my story, the story of me and my twin brother Billy whom you never knew. How I wish you had. It is a true story and I did not want it to die with me.

When I was young I kept a diary, not an everyday diary. I didn’t write in it very often, just whenever I felt like it. Most of it isn’t worth the reading and I’ve already thrown it away – I’ve lived an ordinary sort of life. But for a few months a long, long time ago, my life was not ordinary at all. This is the diary of those few months.

Do you remember you always used to ask where Zanzibar came from? (You called him “Marzipan” when you were small.) I never told you, did I? I never told anyone. Well, now you’ll find out at last.

Goodbye, dear Michael, and God bless you.

Your Great-aunt Laura

PS I hope you like my little sketches. I’m a better artist than I am a writer, I think. When I come back in my next life – and I shall – I shall be a great artist. I’ve promised myself.

I love Grandpa’s farm. When I was younger I’d go down there whenever I could; but I didn’t just go for the farm. I went for Grandpa and his stories too …

There were swing boats up around the village green and a carousel and pasties and toffee apples and lemonade and then in the afternoon we had games down on West Park Farm. We did all sorts of egg and spoon races and sack races three legged races skipping races. You name it we did it. But best of all was chicken chasing. They let some poor old fowl loose in the middle of the field and old Farmer Northley waved his flag and off we went after him, the fowl not old Farmer Northley. And if you caught him well then he was yours to keep. We had some fun and games I can tell you. You could see more bloomers and petticoats on Mayday up in Iddesleigh than was good for a chap. Every year I went after that cockerel just like everyone else but I never caught him.