Полная версия

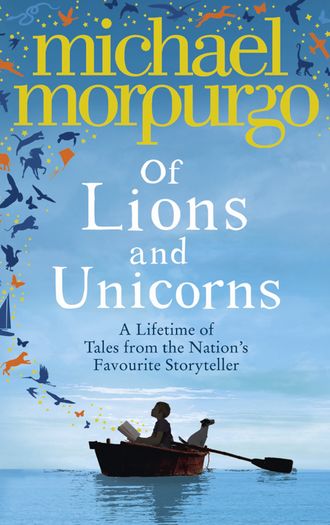

Of Lions and Unicorns: A Lifetime of Tales from the Master Storyteller

I was emptying the wheelbarrow on to the muck heap when I felt someone behind me. I turned round. She was older than I remembered her, greyer in the face, and more frail. She was dressed in jeans and a rough sweater this time, and seemed to be covered in white powder, as if someone had thrown flour at her. Even her cheeks were smudged with it. She glowed when she smiled.

“Where’s there’s muck there’s money, that’s what they say,” she laughed; and then she shook her head. “Not true, I’m afraid, Bonnie. Where there’s muck, there’s magic. Now that’s true.” I wasn’t sure what she meant by that. “Horse muck,” she went on by way of explanation. “Best magic in the world for vegetables. I’ve got leeks in my garden longer than, longer than …” She looked around her. “Twice as long as your bicycle pump. All the soil asks is that we feed it with that stuff, and it’ll do anything we want it to. It’s like anything, Bonnie, you have to put in more than you take out. You want some tea when you’ve finished?”

“Yes please.”

“Come up to the house then. You can have your money.” She laughed at that. “Maybe there is money in muck after all.”

As I watched her walk away, a small yappy dog came bustling across the lawn, ran at her and sprang into her arms. She cradled him, put him over her shoulder and disappeared into the house.

I finished mucking out the stable as quickly as I could, shook out some fresh straw, filled up the water buckets and led Peg back in. I gave her a goodbye kiss on the nose and rode my bike up to the house.

I found her in the kitchen, cutting bread.

“I’ve got peanut butter or honey,” she said. I didn’t like either, but I didn’t say so.

“Honey,” I said. She carried the mugs of tea, and I carried the plate of sandwiches. I followed her out across a cobbled courtyard, accompanied by the yappy dog, down some steps and into a great glass building where there stood a gigantic white horse. The floor was covered in newspaper, and everywhere was crunchy underfoot with plaster. The shelves all around were full of sculpted heads and arms and legs and hands. A white sculpture of a dog stood guard over the plate of sandwiches and never even sniffed them. She sipped her tea between her hands and looked up at the giant horse. The horse looked just like Peg, only a lot bigger.

“It’s no good,” she sighed. “She needs a rider.” She turned to me suddenly. “You wouldn’t be the rider, would you?” she asked.

“I can’t ride.”

“You wouldn’t have to, not really. You’d just sit there, that’s all, and I’d sketch you.”

“What, now?”

“Why not? After tea be all right?”

And so I found myself sitting astride Peg that same afternoon in the stable yard. She was tied up by her rope, pulling contentedly at her hay net and paying no attention to us whatsoever. It felt strange up there, with Peg shifting warm underneath me. There was no saddle, and she asked me to hold the reins one-handed, loosely, to feel “I was part of the horse”. The worst of it was that I was hot, stifling hot, because she had dressed me up as an Arab. I had great swathes of cloth over and around my head and I was draped to my feet with a long heavy robe so that nothing could be seen of my jeans or sweater or wellies.

“I never told you my name, did I?” said the lady, sketching furiously on a huge pad. “That was rude of me. I’m Liza. When you come tomorrow, you can give me a hand making you if you like. I’m not as strong as I was, and I’m in a hurry to get on with this. You can mix the plaster for me. Would you like that?” Peg snorted and pawed the ground. “I’ll take that as a yes, shall I?” She laughed, and walked round behind the horse, turning the page of her sketch pad. “I want to do one more from this side and one from the front, then you can go home.”

Half an hour later when she let me down and unwrapped me, my bottom was stiff and sore.

“Can I see?” I asked her.

“I’ll show you tomorrow,” she said. “You will come, won’t you?” She knew I would, and I did.

I came every day after that to muck out the stables and to walk Peg, but what I looked forward to most – even more than being with Peg – was mixing up Liza’s plaster for her in the bucket, climbing the stepladder with it, watching her lay the strips of cloth dunked in the wet plaster over the frame of the rider, building me up from the iron skeleton of wire, to what looked at first like an Egyptian mummy, then a riding Arab at one with his horse, his robes shrouding him with mystery. I knew all the while it was me in that skeleton, me inside that mummy. I was the Arab sitting astride his horse looking out over the desert. She worked ceaselessly, and with such a fierce determination that I didn’t like to interrupt. We were joined together by a common, comfortable silence.

At the end of a month or so we stood back, the two of us, and looked up at the horse and rider, finished.

“Well,” said Liza, her hands on her hips. “What do you think, Bonnie?”

“I wish,” I whispered, touching the tail of the horse, “I just wish I could do it.”

“But you did do it, Bonnie,” she said and I felt her hand on my shoulder. “We did it together. I couldn’t have done it without you.” She was a little breathless as she spoke. “Without you, that horse would never have had a rider. I’d never have thought of it. Without you mixing my plaster, holding the bucket, I couldn’t have done it.” Her hand gripped me tighter. “Do you want to do one of your own?”

“I can’t.”

“Of course you can. But you have to look around you first, not just glance, but really look. You have to breathe it in, become a part of it, feel that you’re a part of it. You draw what you see, what you feel. Then you make what you’ve drawn. Use clay if you like, or do what I do and build up plaster over a wire frame. Then set to work with your chisel, just like I do, until it’s how you want it. If I can do it, you can do it. I tell you what. You can have a corner of my studio if you like, just so long as you don’t talk when I’m working. How’s that?”

So my joyous spring blossomed into a wonderful summer. After a while, I even dared to ride Peg bareback sometimes on the way back to the stable yard; and I never forgot what Liza told me. I looked about me. I listened. And the more I listened and the more I looked, the more I felt at home in this new world. I became a creature of the place. I belonged there as much as the wren that sang at me high on the vegetable garden wall, as much as the green dragonfly hovering over the pool by the water buffalo. I sketched Peg. I sketched Big Boy (I couldn’t sketch Chip – he just came out round). I bent my wire frames into shape and I began to build my first horse sculpture, layer on layer of strips of cloth dunked in plaster just like Liza did. I moulded them into shape on the frame, and when they dried I chipped away and sanded. But I was never happy with what I’d done.

All this time, Liza worked on beside me in the studio, and harder, faster, more intensely than ever. I helped her whenever she asked me too, mixing, holding the bucket for her, just as I had done before.

It was a Rising Christ, she said, Christ rising from the dead, his face strong, yet gentle too, immortal it seemed; but his body, vulnerable and mortal. From time to time she’d come over and look at my stumpy effort that looked as much like a dog as a horse to me, and she would walk round it nodding her approval. “Coming on, coming on,” she’d say. “Maybe just a little bit off here perhaps.” And she’d chisel away for a minute or two, and a neck or leg would come to sudden life.

I told her once, “It’s like magic.”

She thought for a moment, and said, “That’s exactly what it is, Bonnie. It’s a God-given thing, a God-given magic, and it’s not to be wasted. Don’t waste it, Bonnie. Don’t ever waste it.”

The horse and rider came back from the foundry, bronze now and magnificent. I marvelled at it. It stood outside her studio, and when it caught the red of the evening sun, I could scarcely take my eyes off it. But these days Liza seemed to tire more easily, and she would sit longer over her tea, gazing out at her horse and rider.

“I am so pleased with that, Bonnie,” she said, “so pleased we did it together.”

The Christ figure was finished and went off to the foundry a few weeks before I had to go on my summer holiday. “By the time you come back again,” said Liza, “it should be back. It’s going to hang above the door of the village church. Isn’t that nice? It’ll be there for ever. Well, not for ever. Nothing is for ever.”

The holiday was in Cornwall. We stayed where we always did, in Cadgwith, and I drew every day. I drew boats and gulls and lobster pots. I made sculptures with wet sand – sleeping giants, turtles, whales – and everyone thought I was mad not to go swimming and boating. The sun shone for fourteen days. I never had such a perfect holiday, even though I didn’t have my bike, or Peg or Liza with me.

My first day back, the day before school began, I cycled out to Liza’s place with my best boat drawing in a stiff envelope under my sweater. The stable yard was deserted. There were no horses in the fields. Peg wasn’t in her stable and I could find no one up at the house, no Liza, no yappy dog. I stopped in the village to ask but there was no one about. It was like a ghost village. Then the church bell began to ring. I leant my bike up against the churchyard wall and ran up the path. There was Liza’s Rising Christ glowing in the sun above the doorway, and inside they were singing hymns.

I crept in, lifting the latch carefully so that I wouldn’t be noticed. The hymn was just finishing. Everyone was sitting down and coughing. I managed to squeeze myself in at the end of a pew and sat down too. The church was packed. A choir in red robes and white surplices sat on either side of the altar. The vicar was taking off his glasses and putting them away. I looked everywhere for Liza’s wild white curls, but could not find her. It was difficult for me to see much over everyone’s heads. Besides, some people were wearing hats, so I presumed she was too and stopped looking for her. She’d be there somewhere.

The vicar began. “Today was to be a great day, a happy day for all of us. Liza was to unveil her Rising Christ above the south door. It was her gift to us, to all of us who live here, and to everyone who will come here to our church in the centuries to come. Well, as we all now know, there was no unveiling, because she wasn’t here to do it. On Monday evening last she watched her Rising Christ winched into place. She died the next day.”

I didn’t hear anything else he said. It was only then that I saw the coffin resting on trestles between the pulpit and the lectern, with a single wreath of white flowers laid on it, only then that I took in the awful truth.

I didn’t cry as the coffin passed right by me on its way out of the church. I suppose I was still trying to believe it. I stood and listened to the last prayers over the grave, numb inside, grieving as I had never grieved before, or since, but still not crying. I waited until almost everyone had gone and went over to the grave. A man was taking off his jacket and hanging it on the branch of a tree. He spat on his hands, rubbed them and picked up his spade. He saw me. “You family?” he said.

“Sort of,” I replied. I reached inside my sweater and pulled out the boat drawing from Cadgwith. “Can you put it in?” I asked. “It’s a drawing. It’s for Liza.”

“Course,” he said, and he took it from me. “She’d like that. Fine lady, she was. The things she did with her hands. Magic, pure magic.”

It was just before Christmas the same year that a cardboard tube arrived in the post, addressed to me. I opened it in the secrecy of my room. A rolled letter fell out, typed and very short.

Dear Miss Mallet,

In her will, the late Liza Bonallack instructed us, her solicitors, to send you this drawing. We would ask you to keep us informed of any future changes of address.

With best wishes.

I unrolled it and spread it out. It was of me sitting on Peg, swathed in Arab clothes. Underneath was written:

For dearest Bonnie,

I never paid you for all that mucking out, did I? You shall have this instead, and when you are twenty-one you shall have the artist’s copy of our horse and rider sculpture. But by then you will be doing your own sculptures. I know you will.

God bless,

Liza.

So here I am, nearly thirty now. And as I look out at the settling snow from my studio, I see Liza’s horse and rider standing in my back garden, and all around, my own sculptures gathered in silent homage.

I wondered if any of the people I had known then might still be there; the three Stebbing sisters perhaps, who lived together in the big house with honeysuckle over the porch, very proper people so Mother always wanted me to be on my best behaviour. It was no more than a stone’s throw from the sea and there always seemed to be a gull perched on their chimney pot. I remembered how I’d fallen ignominiously into their goldfish pond and had to be dragged out and dried off by the stove in the kitchen with everyone looking askance at me, and my mother so ashamed. Would I meet Bennie, the village thug who had knocked me off my bike once because I stupidly wouldn’t let him have one of my precious lemon sherbets? Would he still be living there? Would we recognise one another if we met?

The whole silly confrontation came back to me as I walked. If I’d had the wit to surrender just one lemon sherbet he probably wouldn’t have pushed me, and I wouldn’t have fallen into a bramble hedge and had to sit there humiliated and helpless as he collected up my entire bagful of scattered lemon sherbets, shook them triumphantly in my face, and then swaggered off with his cronies, all of them scoffing at me, and scoffing my sweets too. I touched my cheek then as I remembered the huge thorn I had found sticking into it, the point protruding inside my mouth. I could almost feel it again with my tongue, taste the blood. A lot would never have happened if I’d handed over a lemon sherbet that day.

That was when I thought of Mrs Pettigrew and her railway carriage and her dogs and her donkey, and the whole extraordinary story came flooding back crisp and clear, every detail of it, from the moment she found me sitting in the ditch holding my bleeding face and crying my heart out.

She helped me up on to my feet. She would take me to her home. “It isn’t far,” she said. “I call it Dusit. It is a Thai word which means ‘halfway to heaven’.” She had been a nurse in Thailand, she said, a long time ago when she was younger. She’d soon have that nasty thorn out. She’d soon stop it hurting. And she did.

The more I walked the more vivid it all became: the people, the faces, the whole life of the place where I’d grown up. Everyone in Bradwell seemed to me to have had a very particular character and reputation, unsurprising in a small village, I suppose: Colonel Burton with his clipped moustache, who had a wife called Valerie, if I remembered right, with black pencilled eyebrows that gave her the look of someone permanently outraged – which she usually was. Neither the colonel nor his wife was to be argued with. They ruled the roost. They would shout at you if you dropped sweet papers in the village street or rode your bike on the pavement.

Mrs Parsons, whose voice chimed like the bell in her shop when you opened the door, liked to talk a lot. She was a gossip, Mother said, but she was always very kind. She would often drop an extra lemon sherbet into your paper bag after she had poured your quarter pound from the big glass jar on the counter. I had once thought of stealing that jar, of snatching it and running off out of the shop, making my getaway like a bank robber in the films. But I knew the police would come after me in their shiny black cars with their bells ringing, and then I’d have to go to prison and Mother would be cross. So I never did steal Mrs Parsons’s lemon sherbet jar.

Then there was Mad Jack, as we called him, who clipped hedges and dug ditches and swept the village street. We’d often see him sitting on the churchyard wall by the mounting block eating his lunch. He’d be humming and swinging his legs. Mother said he’d been fine before he went off to the war, but he’d come back with some shrapnel from a shell in his head and never been right since, and we shouldn’t call him Mad Jack, but we did. I’m ashamed to say we baited him sometimes too, perching alongside him on the wall, mimicking his humming and swinging our legs in time with his.

But Mrs Pettigrew remained a mystery to everyone. This was partly because she lived some distance from the village and was inclined to keep herself to herself. She only came into the village to go to church on Sundays, and then she’d sit at the back, always on her own. I used to sing in the church choir, mostly because Mother made me, but I did like dressing up in the black cassock and white surplice and we did have a choir outing once a year to the cinema in Southminster – that’s where I first saw Snow White and Bambi and Reach for the Sky. I liked swinging the incense too, and sometimes I got to carry the cross, which made me feel very holy and very important. I’d caught Mrs Pettigrew’s eye once or twice as we processed by, but I’d always looked away. I’d never spoken to her. She smiled at people, but she rarely spoke to anyone; so no one spoke to her – not that I ever saw anyway. But there were reasons for this.

Mrs Pettigrew was different. For a start she didn’t live in a house at all. She lived in a railway carriage, down by the sea wall with the great wide marsh all around her. Everyone called it Mrs Pettigrew’s Marsh. I could see it best when I rode my bicycle along the sea wall. The railway carriage was painted brown and cream and the word PULLMAN was printed in big letters all along both sides above the windows. There were wooden steps up to the front door at one end, and a chimney at the other. The carriage was surrounded by trees and gardens, so I could only catch occasional glimpses of her and her dogs and her donkey, bees and hens. Tiny under her wide hat, she could often be seen planting out in her vegetable garden, or digging the dyke that ran around the garden like a moat, collecting honey from her beehives perhaps or feeding her hens. She was always outside somewhere, always busy. She walked or stood or sat very upright, I noticed, very neatly, and there was a serenity about her that made her unlike anyone else, and ageless too.

But she was different in another way. Mrs Pettigrew was not like the rest of us to look at, because Mrs Pettigrew was “foreign”, from somewhere near China, I had been told. She did not dress like anyone else either. Apart from the wide-brimmed hat, she always wore a long black dress buttoned to the neck. And everything about her, her face and her hands, her feet, everything was tidy and tiny and trim, even her voice. She spoke softly to me as she helped me to my feet that day, every word precisely articulated. She had no noticeable accent at all, but spoke English far too well, too meticulously, to have come from England.

So we walked side by side, her arm round me, a soothing silence between us, until we turned off the road on to the track that led across the marsh towards the sea wall in the distance. I could see smoke rising straight into the sky from the chimney of the railway carriage.

“There we are: Dusit,” she said. “And look who is coming out to greet us.”

Three greyhounds were bounding towards us followed by a donkey trotting purposefully but slowly behind them, wheezing at us rather than braying. Then they were gambolling all about us, and nudging us for attention. They were big and bustling, but I wasn’t afraid because they had nothing in their eyes but welcome.

“I call the dogs Fast, Faster and Fastest,” she told me. “But the donkey doesn’t like names. She thinks names are for silly creatures like people and dogs who can’t recognise one another without them. So I call her simply Donkey.” Mrs Pettigrew lowered her voice to a whisper. “She can’t bray properly – tries all the time but she can’t. She’s very sensitive too; takes offence very easily.” Mrs Pettigrew took me up the steps into her railway carriage home. “Sit down there by the window, in the light, so I can make your face better.”

I was so distracted and absorbed by all I saw about me that I felt no pain as she cleaned my face, not even when she pulled out the thorn. She held it out to show me. It was truly a monster of a thorn. “The biggest and nastiest I have ever seen,” she said, smiling at me. Without her hat on she was scarcely taller than I was. She made me wash out my mouth and bathed the hole in my cheek with antiseptic. Then she gave me some tea which tasted very strange but warmed me to the roots of my hair. “Jasmine tea,” she said. “It is very healing, I find, very comforting. My sister sends it to me from Thailand.”

The carriage was as neat and tidy as she was: a simple sitting room at the far end with just a couple of wicker chairs and a small table by the stove. And behind a half-drawn curtain I glimpsed a bed very low on the ground. There was no clutter, no pictures, no hangings, only a shelf of books that ran all the way round the carriage from end to end. From where I was sitting I could see out over the garden, then through the trees to the open marsh beyond.

“Do you like my house, Michael?” She did not give me time to reply. “I read many books, as you see,” she said. I was wondering how it was that she knew my name, when she told me. “I see you in the village sometimes, don’t I? You’re in the choir, aren’t you?” She leant forward. “And I expect you’re wondering why Mrs Pettigrew lives in a railway carriage.”

“Yes,” I said.

The dogs had come in by now and were settling down at our feet, their eyes never leaving her, not for a moment, as if they were waiting for an old story they knew and loved.

“Then I’ll tell you, shall I?” she began. “It was because we met on a train, Arthur and I – not this one, you understand, but one very much like it. We were in Thailand. I was returning from my grandmother’s house to the city where I lived. Arthur was a botanist. He was travelling through Thailand collecting plants and studying them. He painted them and wrote books about them. He wrote three books; I have them all up there on my shelf. I will show you one day – would you like that? I never knew about plants until I met him, nor insects, nor all the wild creatures and birds around us, nor the stars in the sky. Arthur showed me all these things. He opened my eyes. For me it was all so exciting and new. He had such a knowledge of this wonderful world we live in, such a love for it too. He gave me that, and he gave me much more: he gave me his love too.

“Soon after we were married he brought me here to England on a great ship – this ship had three big funnels and a dance band – and he made me so happy. He said to me one day on board that ship, ‘Mrs Pettigrew –’ he always liked to call me this – ‘Mrs Pettigrew, I want to live with you down on the marsh where I grew up as a boy.’ The marsh was part of his father’s farm, you see. ‘It is a wild and wonderful place,’ he told me, ‘where on calm days you can hear the sea breathing gently beyond the sea wall, or on stormy days roaring like a dragon, where larks rise and sing on warm summer afternoons, where stars cascade on August nights.’