Полная версия

The Fatal Strand

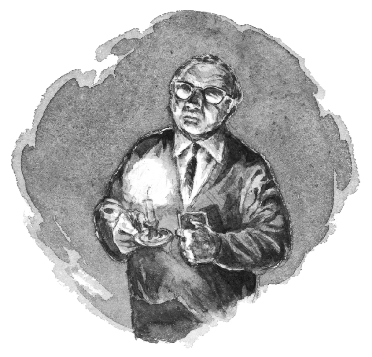

It was obvious that the man was fighting to remain calm, but he was so excited that his breaths were shallow and gasping. With his already large-seeming eyes widening behind the thick lenses of his spectacles, he came to the arched doorway and placed his stubby fingers upon the bronze figure at his left.

Timidly, he stared in at the museum’s gloom-laden interior and took another gulp of air, as if he were swigging a measure of whisky for courage. Then, with an acknowledging glance at Neil, the man calmed himself. He had been longing for this moment for so long that he wanted to cherish it in his memory ever afterwards.

‘First impressions,’ Neil heard him mumble to himself. ‘I must be free to receive all I can. Come on Austen, old lad – be the blank paper, the empty jug, the untrodden snow.’

‘What are you waiting for?’ Miss Ursula called. ‘Be quick to enter.’

Half-closing his eyes, Austen Pickering stepped purposefully over the threshold and drew a deep, rapturous breath. For several moments he stood quite still with his head tilted back, and Neil began to wonder if the old man had gone into a trance.

But the peculiar silence did not last, for Mr Pickering presently opened his eyes and looked gravely about him.

‘Yes!’ he sighed. ‘I was right. But so many – hundreds upon hundreds. I never dreamed!’

‘What is it?’ Neil asked.

‘Most incredible!’ the man exclaimed. ‘I never expected so staggering a number. Quite astounding.’

Neil exchanged looks with the Chief Inspector, but Hargreaves’ hollow-cheeked face was solemn and the boy couldn’t guess what he was thinking.

Her chin resting upon the banister, Edie grimaced and took an instant dislike to the strange newcomer. Everything about the man’s bearing and attire suggested the strict, military discipline with which he ordered his life. What was left of his tightly waved hair was too neatly combed, a veritable knuckle of a knot secured his regimental tie in place, and his brown brogues shone like chestnuts freshly popped from their casing.

During her untame life in the bomb sites, Edie had spent too long distrusting and evading the figures of authority who had tried to catch her to abandon those natural suspicions now. To her, this fastidious little man was no different from the countless air-raid wardens she had hated; Austen Pickering wore his clothes like a uniform and she despised him for that fact alone.

Forsaking him in revolt, she looked to see what Miss Ursula made of him and was intrigued to read in the old woman’s face a considerable degree of approval.

‘You admire my museum?’ Miss Ursula said suddenly.

Mr Pickering turned to her and peered over the rim of his glasses. ‘Admire is not the word I would have chosen, Madam.’

‘That is to be expected,’ she said. ‘From the many letters I have received from you, I would have been sorely disappointed if you had not felt the pulse of life which courses through this building.’

‘Pulse of life!’ the man spluttered in disbelief. ‘I assure you, Madam, that it is the pain of the anguished dead which I feel – and that most deeply.’

The taffeta of Miss Ursula’s black gown rustled faintly as she stirred and gripped the banister rail a little tighter. ‘Tell me what it is that you sense,’ she commanded. ‘When you walked through that door – what was it like?’

The ghost hunter knitted his brows and in the grave tone he reserved for these matters said, ‘The atmosphere is electric – charged like a battery. No, more like a dam that is close to bursting. If nothing is done to release the pressure then I cannot begin to imagine what will occur. The tension is unbearable.’

Casting his gaze about the dim entrance hall, from the small window of the ticket booth to the drab watercolours which mobbed the panelled walls, he tapped his fingertips together and nodded grimly.

‘I’ve never been in so ancient a place. It’s staggering. How many trapped souls are locked in here? How many poor unfortunates have never been able to break free of its jealous clutch?’

But Miss Ursula had heard and seen enough for the time being. ‘That will be for you to discover,’ she told him. ‘I wish your investigations to commence at once. The caretaker’s son shall guide you around the museum. If there are tormented souls locked in here, you have my permission to do whatever you please with them. Now, close the door – the draught is intolerable.’

Neil glanced apologetically at the Chief Inspector who was still waiting outside, but Hargreaves was not in the least bit offended.

‘Close it, I say!’ Miss Ursula commanded.

Hargreaves moved away from the entrance. ‘I’ll be around should you need me,’ he called to Neil as the boy reluctantly pushed the door shut. ‘Urdr knows, those of us who are left will be here.’

The oaken door shuddered in its frame and Neil glared up at the imperious figure upon the stairs.

‘There’s no need to be so rude!’ he shouted.

But Miss Ursula had her back to him and was already ascending to the first floor. Giving the stranger a final suspicious glance, Edie Dorkins pulled an impudent face and capered after her.

Austen Pickering could only shake his head in disappointment. ‘Sad want of manners,’ he murmured.

‘Ignore them,’ Neil began. ‘They’re both bats.’

The old man regarded him for a moment. ‘I’ve come across worse. There’s no escaping it in my field of study. When you talk about phantoms and the unquiet dead to people, it seems to bring out the worst in them. I’ve been called more names than I can remember, but so long as the job gets done, they can call me twice as many again.’

Pausing, he looked at the raven sitting upon the boy’s shoulder and winked at him in amusement. ‘That’s a dandy specimen you’ve got there, lad,’ he said peering at the bird with interest. ‘However did you come by him?’

Quoth held his head up proudly whilst the man viewed him and turned his head so that his best side showed.

‘Vain little beggar, too,’ Mr Pickering observed.

‘He that be a foe of beauty is an enemy of nature,’ the raven retorted.

The man started and looked at Neil, as though suspecting him of ventriloquism. Then he laughed and removed his spectacles to polish the lenses. ‘A long time I’ve been waiting to get inside this place,’ he declared. ‘I told myself I’d have to expect all kinds, but I wasn’t counting on a talking raven to be my first surprise.’

Returning his glasses to their rightful place upon his nose, Austen Pickering smiled happily. ‘This is birthdays and Christmas all come at once,’ he explained to Neil. ‘I hardly know where to start. It’s like being given one enormous present, but too excited to peep inside the wrapping paper.’

Walking towards the door which led to the ground floor collections, he rubbed his hands together with an almost childlike glee. ‘You don’t have to show me around if you don’t want to. I’d be perfectly content to wander about on my own.’

‘No,’ Neil replied. ‘I’d like to. What you said about there being trapped souls in here … do you mean it’s haunted?’

At once Mr Pickering grew serious again. ‘Can you doubt it?’ he cried. ‘You who live in this revolting building?’

‘I believe you – honest I do,’ Neil assured him, and his thoughts flew to his friend Angelo Signorelli.

When the Chapmans had first come to stay in The Wyrd Museum, Neil had encountered the soul of that unfortunate American airman in The Separate Collection. There, in one of the display cabinets, Angelo’s spirit had been imprisoned for over fifty years, locked within the woolly form of a shabby old Teddy bear. Together, they had journeyed back into the past to save the life of Jean Evans, the woman Angelo had loved. But Ted had chosen to remain in that time and Neil still missed him.

Addressing Austen Pickering again, Neil asked, ‘When I saw you that time, out in the street, you said this place was like a psychic sponge – that it trapped souls and kept them. What you did just then, when you came in – are you psychic?’

The man stared at him. It was unusual for anyone to accept the things he said, but this boy was doing his best – even trying to understand. ‘I’m blessed with a very modest gift,’ he murmured. ‘From the moment I stepped inside this horror, I felt the unending torture of those who should have crossed over but are still bound to this world. This place has known untold deaths during its different roles throughout the ages.’

‘I know that it used to be an insane asylum.’

‘Oh, it’s been a lot more than that, lad. I’ve done my homework on this miserable pile of bricks, researching back as far as the scant records allow. Orphanage, a workhouse for the poverty-stricken silk weavers, before that a pest house and going even further back – a hospital for lepers. Think of all the suffering and anguish these walls have absorbed. No one can imagine the number of hapless victims that this monstrous structure keeps locked within its rooms, condemned to wander these floors for eternity. The poor wretches have been ignored for far too long.’

Clapping his hands together, he raised his voice and announced in a loud voice which boomed out like that of a drill sergeant. ‘Well, I’m here now – Austen Pickering, ghost hunter. Here to listen to their cries and, no matter what it takes, I’m going to help them.’

CHAPTER 6 TWEAKING THE CORK

The rest of Neil’s morning was taken up showing Austen Pickering around The Wyrd Museum. The man marvelled at every room and each new display. He was a very methodical individual who took great pains to ensure that no exhibit was overlooked, reading each of their faded labels. Therefore, the tour took longer than Neil had anticipated, for the old man found everything to be of interest and had an opinion about all that he saw.

Quoth found this a particularly tiring trait and yawned many times, nodding off on several occasions, almost falling from Neil’s shoulder.

Whilst they were in The Roman Gallery, Miss Celandine came romping in, dressed in her gown of faded ruby velvet and chattering away to herself. The old woman was giggling shrilly, as if in response to some marvellous joke, but as soon as she saw Neil and the old man she froze, and a hunted look flashed across her walnut-wrinkled face.

‘Don’t leave me!’ she squealed to her invisible companions. ‘You said we might go to the dancing. You did! You did! Come back – wait for me! Wait!’ And with her plaits swinging behind her, she fled back the way she had come.

Austen Pickering raised his eyebrows questioningly and Neil shrugged. ‘She’s not all there, either,’ he explained.

‘The vessel of her mind hast set sail, yet she didst remain ashore,’ Quoth added.

Their snail-like progress through the museum was delayed even further by the ghost hunter’s habit of pausing at odd moments whilst he jotted down his impressions in a neat little notebook.

‘You never know what may turn out to be important,’ he told Neil. ‘A trifling detail seen here, but forgotten later, might just be the key I’ll be looking for in my work. The investigator must be alert at all times and record what he can. It might seem daft and over-meticulous, but you have to be thorough and not leave any holes for the sceptics to pick at. I pride myself that no one could accuse me of being slipshod. Everything is written up and filed. No half measures for me. I’ve got a whole room filled with dossiers and indexes back home up north, accounts and news clippings of each case I’ve had a hand in. It was the Northern Echo what first called me a ghost hunter, although … Blimey – would you look at this!’

They had climbed the stairs to the first floor where great glass cases, like huge fish tanks, covered the walls of a long passage, making the way unpleasantly narrow. Neil did not like this corridor, for every cabinet contained a forlorn-looking specimen of the taxidermist’s macabre art.

They were the sad remnants of the once fabulous menagerie of Mr Charles Jamrach, the eccentric purveyor of imported beasts, whose emporium in the East End of London had housed a veritable ark of animals during Victorian times. After both he and his son had died, the last of the livestock was sold off and a portion of it had eventually found its way into The Wyrd Museum.

Stuffed baboons and spider monkeys swung from aesthetically arranged branches. A pair of hyenas with frozen snarls looked menacing before an African diorama, incongruous next to an overstuffed, whiskery walrus gazing out with large doe eyes. In the largest case of all, a mangy tiger peered from an artificial jungle.

In spite of the fact that the cases were securely sealed, a fine film of dust coated each specimen and the tiger’s fur crawled with an infestation of moths.

Shuddering upon Neil’s shoulder, Quoth stared woefully at the crystal domes which housed exotic, flame-coloured birds, and whimpered with sorrow at the sight of a glorious peacock, the sapphires and emeralds of its tail dimmed by an obscuring mesh of filthy cobwebs.

‘Alack!’ he croaked. ‘How sorry is thy situation – most keenly doth this erstwhile captive know the despond of thine circumstance.’

‘Your raven isn’t comfortable here,’ Mr Pickering commented. ‘I don’t blame him. The Victorians had a perverse passion for displaying the creatures they had slaughtered. Disgusting, isn’t it? Beautiful animals reduced to nothing more than trophies and conversation pieces. You might as well stick a lampshade on them, or use them as toilet-roll holders.’

‘I’m not keen on this bit, either,’ Neil agreed, pushing open a door. ‘If we go through here we can cut it out and go around. There’s more galleries this way – even an Egyptian one.’

Leaving the glass cases and their silent, staring occupants behind them, they continued with the tour. It was nearly lunchtime and Neil was ravenous, remembering he hadn’t eaten anything since the previous day. But the boy wanted to show Mr Pickering one room in particular.

Eventually they arrived at the dark interior of The Egyptian Suite and the old man gazed at the three sarcophagi it contained. ‘Not satisfied with parrots and monkeys,’ he mumbled in revulsion. ‘Even people are put on display. Is it any wonder the atmosphere is filled with so much pain?’

But Neil was anxious for the man to enter the adjoining room, for here was The Separate Collection.

Moving away from the hieroglyphs and mummies, Mr Pickering followed his young guide, but the moment he stepped beneath the lintel of the doorway which opened into The Separate Collection, he gave a strangled shriek and fell back.

‘What is it?’ Neil cried. The man looked as though he was going to faint.

Mr Pickering shooed him away with a waggle of his small hands and staggered from the door, returning to the gloom of The Egyptian Suite.

‘Can’t … can’t go in there!’ he choked.

Neil stared at him in dismay. He hadn’t been expecting such an extreme reaction. The man’s face was pricked with sweat and his eyes bulged as though his regimental tie had become a strangling noose.

Blundering against the far wall, Austen Pickering’s gasping breaths began to ease and he leaned upon one of the sarcophagi until his strength was restored.

‘My, my,’ he spluttered at length. ‘How stupid. Austen, old lad, you should’ve expected it. You told yourself there had to be one somewhere. Oh, but I never dreamed it would be so … well, there it is.’

Quoth fidgeted uncertainly. ‘Squire Neil,’ he muttered, ‘methinks yon fellow may prove a swizzling tippler. The ale hath malted and mazed his mind.’

‘Are you all right?’ Neil asked the old man. ‘You look awful. What happened?’

Mr Pickering mopped his forehead and stared past the boy into the room beyond. ‘A fine old fool I am,’ he wheezed. ‘I’m sorry if I startled you, lad. It’s that room, I can’t enter – at least not yet.’

‘How sayest the jiggety jobbernut?’ Quoth clucked.

‘What stopped you?’ the boy asked, ignoring the raven. ‘Is it one of the exhibits?’

The ghost hunter shook his head. He had recovered from the shock and an exhilarated grin now lit his face.

‘All the classic case studies tell of them,’ he gabbled, more to himself than for Neil’s benefit. ‘Though I’ve come across the more usual cold spots before, I’ve never truly experienced this phenomenon. This really is a red-letter day.’

‘What is?’ Neil demanded.

Mr Pickering clicked his fingers as though expecting the action to organise and set his thoughts in order.

‘Occasionally,’ he explained excitedly, ‘a haunted site will have a nucleus – a centre of operations, if you like, where all the negative forces and paranormal activity begin and flow out from.’

‘And you think it’s The Separate Collection?’ Neil murmured. ‘I suppose it would make sense. There’s a lot of mad stuff in there.’

‘I’m quite certain of it. But the intensity – it’s incredible. Oho, it didn’t want me to go in, that it didn’t. It knows why I’m here and doesn’t want to let its precious spectres go. Well, we’ll see about that.’

Neil gazed into the large, shadow-filled room which lay beyond The Egyptian Suite and recalled how frightened he had been when he had first moved into The Wyrd Museum. He remembered how the building had almost seemed to be tricking him, deceiving his sense of direction – leading him round and around until finally he was delivered to that very place, where the exhibits were eerie and sinister.

A shout from Ted had put a stop to it back then, but the spirit of the airman who had possessed the stuffed toy was finally at rest.

‘Are you saying that the building is alive?’ he finally ventured. ‘Watching and listening to us?’

The old man gave a brisk shake of the head. ‘Not alive, no, not in the sense that we understand. That would imply intelligence and I wouldn’t go so far as to say that. I do believe, however, that there is a presence which permeates every brick and tile – an awareness, if you like. Call it a mass accumulation of history and anguish, recorded on to the ether, which operates on some very basic and primitive level. That is what we are up against. It is that force which feeds upon the energies of both the living and the deceased, and binds them to itself.’

Gingerly moving towards the doorway once more, the ghost hunter considered The Separate Collection and a gratified smile beamed across his craggy face. ‘This is amazing,’ he declared. ‘Absolutely amazing. There mustn’t be any more delay; the investigation proper will have to commence at once. But first things first. I’ll have to go back and fetch my equipment.’

Infected by Mr Pickering’s delight, Neil laughed. ‘What are you going to do?’ he asked. ‘An exorcism?’

The ghost hunter calmed himself. ‘Give over,’ he replied. ‘I can’t do that. We must learn all we can first. Besides, I don’t want to jump in at the deep end. I’ll work through the museum systematically, room by room and floor by floor. That Separate Collection is the supernatural heart of this place and I’m not ready for the surprises it might throw at me – not yet at any rate.’

When Austen Pickering left The Wyrd Museum to return to his lodgings, Neil hastened back to the caretaker’s apartment, taking care to leave Quoth in The Fossil Room once again. It proved to be a wise precaution, for Brian Chapman was in a terrible mood. He had only been awake for half an hour and it was now nearly two o’clock.

When he realised the time, he had looked into his sons’ bedroom but found it empty. Hurrying into the kitchen, he discovered a pool of spilled milk near the fridge and a bowl of half-eaten cereal in the sink. Tutting, he left the apartment to search for them.

Josh was playing in the walled yard, with a coat pulled on over his pyjamas and a pair of Wellington boots covering his bare feet. The little boy told him that he hadn’t seen his brother all day and that he’d tried to shake his father awake. When his efforts had failed, he had made his own breakfast.

Brian ran his hands through his greasy hair and pinched the bridge of his nose. He’d had an awful night and was now even more determined to look for another job. Anything. Just to get out of this hideous place was all that he craved and nothing anyone could say would change his mind. It wasn’t like him to sleep so late and he was more angry at himself than anyone else.

Neil hated it when his father was like this and decided against mentioning Austen Pickering, for that would certainly have made matters worse. The only course to take was to let Brian calm down. So, shutting himself away from the squall of his father’s temper, the boy calmly began to make sandwiches for them all.

Miss Ursula had not set any new work for Brian to do, so in the afternoon he slipped out, hoping that she wouldn’t notice. Entrusted with looking after Josh, Neil took the four-year-old to find Quoth. The child was scared of the raven at first, but he was soon tickling him under the beak, feeding him ham sandwiches and laughing at his absurd speech.

At four o’clock, a morose jingling announced Austen Pickering’s return and Neil ran to the entrance to admit him. Three large, much-battered suitcases surrounded the grizzle-haired man as he waited upon the steps, and he grumbled to Neil about the exorbitant cost of cabs in London, whilst the boy helped him to haul the luggage inside.

‘You’ve certainly brought enough!’ Neil exclaimed. ‘What sort of equipment have you got in here?’

‘That witch of a landlady told me to sling my hook! Got a terrible tongue on her, that cat has,’ the man puffed, dragging a heavy portmanteau under the sculpted archway. ‘She’s chucked me out – this is everything I had with me. You know, lad, it’s the living what scare me most. The dead I can deal with.’

Neil contemplated the suitcases thoughtfully. ‘So, you’re staying here then?’

‘Makes sense really,’ the ghost hunter replied. ‘I’d have to be spending the nights here anyway, so I might as well stop. No point shelling out for a new room when I won’t even be there. The Websters won’t mind, I’m sure.’

But Neil was not thinking about them; he was wondering what his father would have to say.

‘You know,’ Mr Pickering reflected, ‘I’m sure that nosy woman had been furtling through my stuff. She’d best not have messed with any of my apparatus. It’s already getting dark and I want to get started straight away.’

When Brian Chapman returned to the museum he discovered, to his consternation, that Austen Pickering had taken over one corner of The Fossil Room and was busily setting up his equipment in the rest of the available space. Several of the connecting rooms also contained one or two experiments; lengths of string were fixed across windows and doorways, and a dusting of flour was sprinkled over certain areas of the floor.

Neil’s father regarded the man with irritation. He had certainly made himself at home. His mackintosh was hanging from a segment of vertebrae jutting conveniently from a fine example of an ichthyosaur skeleton set into the far wall. His highly-polished brogues had been placed neatly beneath a cabinet and his feet were now cosily snug in a pair of slippers.

That disease-ridden raven was playing in one of the cases, tugging at a spare pair of braces he had unearthed amongst a pile of vests, and the newcomer himself was talking to his sons about haunted houses.

‘Blood and sand!’ Brian mumbled. ‘It’s one thing after another in here.’

There was, of course, nothing he could do about it. If his eccentric employers wanted to have seances, then it was up to them, but he wasn’t going to permit Josh to remain and listen to this nonsense.

Brian had spent the afternoon trawling the local markets and public houses, asking after casual work, and had eventually ended up in the job centre. His searches had not been successful, but he had brought a bundle of newspapers and leaflets home with him. Leaving the ghost hunter to his own business, he returned to the caretaker’s apartment, with his four-year-old son trailing reluctantly behind.