Полная версия

The Fatal Strand

‘Sorry if I woke you, Madam,’ Hargreaves apologised, ‘but it is important.’

Mrs Rosina shut the door again to slide the chain off, then opened it fully.

‘What is this?’ she asked, folding her arms once again. ‘A dawn raid? Post office ain’t been done over again has it?’

The Chief Inspector cleared his throat. ‘Nothing like that,’ he assured her. ‘I understand you have a Mr Pickering lodging with you. Is that so?’

The woman bristled visibly and she raised her dark eyebrows. ‘I see,’ she drawled with tart disdain. ‘What’s he done?’

‘Nothing, I’d just like to have a few words with him, that’s all.’

‘Look, love, I know it’s early but I don’t look that green, do I?’

‘Is Mr Pickering here or isn’t he?’

Mrs Rosina pursed her lips and the cigarette waggled insolently as though it were a substitute tongue.

‘You’d better come in, then,’ she finally invited.

Removing his cap, the Chief Inspector stepped inside the hall and gazed mildly about him.

‘Well, he’s not down here,’ the landlady was quick to point out. ‘Only me and me old mother have those rooms. What sort of a place do you think this is? That Pickering’s in Room Four, upstairs. This way.’

Leading the policeman up to the first floor landing, the woman gave a wheezing breath. ‘So what do you want him for?’ she insisted, blocking the Chief Inspector’s progress with her substantial form. ‘Got a right to know, ain’t I? I don’t want to be murdered in me bed.’

The Chief Inspector eyed her restlessly. He did not have time for this tedious woman. ‘I have already said that I only wish to speak to your boarder, Madam,’ he repeated, a note of impatience creeping into his voice. ‘I guarantee that you have nothing to worry about.’

‘So you’ve only come to have a cosy little chat with him – at this time of the morning? You must think I’ve just got off the boat. Hoping he can help you with your enquiries, is it? We all know what that means, oh yes.’

‘I’m sorry, Madam,’ Hargreaves interrupted, unsuccessfully attempting to squeeze by her. ‘It really is urgent.’

Mrs Rosina sniffed belligerently, then revolved like a globe upon the axis of her slippers and trotted to the door marked with a plastic number four.

Using the butt of her lighter, she vented some of her irritation by rapping loudly and calling for the occupant of the room to wake up.

‘Hello?’ a muffled, sleepy-sounding voice answered. ‘What is it?’

‘Visitor for you.’

‘If you could give me a minute or two to get dressed …’

The woman threw the Chief Inspector a sullen look. ‘Hope you’ve got some of your lads out back – ’case he scarpers through the window.’

The corners of Hargreaves’ mouth curled into a humouring smile which infuriated her more than ever.

‘Wouldn’t put anything past him, anyway,’ she said sulkily. ‘Bit too quiet, if you know what I mean. Doesn’t talk much – gives nothing away. Been here a couple of months now, on and off. Right through Christmas an’ all, which I thought was downright peculiar.’

Before she could unleash any further spite, in the hope of startling some hint or disclosure from the policeman, the door opened. As she’d been leaning on it, Mrs Rosina nearly fell into the room.

‘Austen Pickering?’ the Chief Inspector inquired.

A short man, with a high forehead encompassed by an uncombed margin of grizzled hair, looked up at him in drowsy astonishment.

‘Inspector Clouseau here wants a word with you,’ Mrs Rosina chipped in.

Her lodger blinked at her behind his large spectacles. ‘With me?’ he asked in surprise. ‘Is something the matter?’

‘You’d know, I’m sure,’ she rejoined in a voice which positively fizzed with acid.

Hargreaves coughed politely. ‘It’s all right, Sir,’ he said. ‘I merely wanted a word with you – in private.’

The landlady ground her teeth together, but she was prevented from speaking her mind on this matter by a voice which called to her from downstairs.

‘Glor?’ came the anxious cry. ‘Is that you, Glor?’

Mrs Rosina scrunched up her face in exasperation and hurried to the landing banister, where she leaned over and shouted down, ‘Quiet, Mother! Go back to bed.’

‘I heard voices, Glor.’

‘We got the flamin’ police in.’

‘Righto, I’ll do a brew then.’

‘No, just get back in your room.’

Returning from the banister, the landlady pouted with pique, for the door to Room Four was now firmly shut and the policeman already inside. Not knowing whether to demand entry or try to overhear what was being said, she crept closer.

However, just when she had decided on the latter course and was pressing her ear to the grubby paintwork, the door was yanked open again, and both her guest and the Chief Inspector bumped straight into her.

‘And you say that I can start right away?’ Austen Pickering asked, pulling on his mackintosh and taking no notice of the large woman in his excitement.

Already striding down the stairs, Hargreaves nodded briskly. ‘They want to see you at once, Sir,’ he said. ‘Made that point very clear when I got the message.’

‘Why now, I wonder?’ the little man gabbled. ‘I’ve written scores of letters, but never received any reply. Has something happened? I mean, why should you come and tell me this? Why the police? I don’t understand. There’s not been an … incident, has there?’

Pausing at the foot of the stairs, Hargreaves stared up at him. ‘She’ll tell you everything you need to know, Sir,’ he said. ‘But don’t worry, this isn’t police business.’

‘Then why …?’

‘Just come with me, please.’

And so Austen Pickering was bundled out of The Bella Vista, and the frosted glass of the front door rattled as he slammed it after him.

Standing in the hallway an elderly, kindly-looking woman gazed after the departing pair, then turned her attention to the staircase to see her daughter Gloria come stomping down.

‘I’m not having this!’ Mrs Rosina stormed. ‘Coppers turning up at all hours – what’ll the neighbours think?’

‘But you don’t speak to any of them, Glor,’ her mother put in. ‘You don’t like them. “Nowt but thieves and spongers,” you said.’

Fumbling with the lighter, her daughter finally lit the cigarette and drew a long, dependent breath. ‘Go an’ play your seventy-eights,’ she exhaled.

‘Don’t you want that cuppa then?’

‘What I want,’ Mrs Rosina snapped between gasps, ‘is to know what’s been going on in my own house! Well, I’m going to find out. No snotty policeman’s going to tell me what I can and can’t know about them what stop here. Where’s them spare keys?’

With her glowing cigarette bobbing before her face, she stamped back up the stairs and her elderly mother tutted after her.

‘I don’t think you should go through that man’s things, Glor,’ she advised. ‘’Tain’t right.’

But Mrs Rosina was too vexed and curious to listen – besides, it wouldn’t be the first time she had rifled through the private belongings of one of her guests. It really was fascinating, not to say revealing, to pry into what some of these people lugged about with them.

In the hallway, the landlady’s mother gave one final shake of her head and ambled back to her own little bedroom. ‘Blood will tell,’ she lamented. ‘Glor’s just as bad as she ever was.’

CHAPTER 5 AWAITING THE CATALYST

Kneeling in front of a large open cupboard in the Websters’ cramped attic apartment, Edie Dorkins sucked her teeth and surveyed the cluttered bric-a-brac of Miss Veronica’s belongings.

Amongst the dusty, neglected jumble were some interesting odds and ends, culled from every age of The Wyrd Museum’s existence. A rolled up bundle of parchments, tied up with a lavender ribbon, revealed a collection of sonnets, letters and poems from the quills of the finest poets and playwrights. There were tiny framed miniatures of all three sisters; the women still appeared old, even though they had posed for the portraits several centuries ago. A purse of moth-eaten velvet contained diverse and sumptuous pieces of jewellery; from quite plain and chunky lumps of twisted gold, to single earrings or broken bracelets which sparked with finely cut gems.

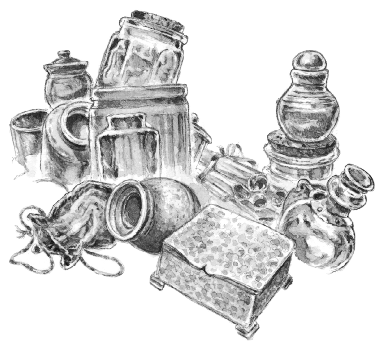

Edie coveted this fabulous treasure and stuffed many of the shiny trinkets into her coat pocket, before crawling a little deeper into the cupboard to see what else she could discover in this fascinating hoard. To her annoyance, her progress was impaired by countless stone jars and bottles which the woman had squeezed into every conceivable space. Edie resented them; they were maddeningly in the way and did not contain anything that appealed to her poaching piracy.

Amongst those many pots were the late Miss Veronica’s innumerable aids to beauty. There were tins of flour and chalk which she had applied to her face; she had fancied that the dramatically bloodless effect granted her a much younger appearance. This grotesquerie was always heightened by a great daubing stripe of garish red from a tub of vermilion ooze, which the old woman had spread thickly across her lips, making her look like a nightmarish clown.

In another vessel, Edie found the lumps of charcoal which Miss Veronica had used to mark out her eyebrows, and a big bottle of green glass contained an unctuous, tarry mixture with which she had dyed her hair. Carelessly piled on top of each other, these receptacles were every shape and size, and maintained a brittle balance which Edie’s foraging threatened to capsize with each fresh incursion.

Sitting in the armchair next to the cold hearth, latticed by the grey light of the early morning which shone weak and pale through the one diamond-crossed window, Miss Ursula tapped her fingers upon the worn upholstery, patiently counting out each slow second. No expression modelled her pinched, camel-like features, but her raw eyes were a testament to the suffering she had endured during the recent hours.

A clattering avalanche of pots and jars caused the woman to jerk her head back and look across at the young girl half hidden inside her dead sister’s cupboard.

‘You will find nothing of note in there, Edith,’ she told her.

Edie rolled backwards and lay on her side, playfully flicking a dead, dusty mouse she had found across the threadbare carpet.

‘Where’s Celandine?’ she asked.

‘I allowed her free movement through the museum. I think it best for her. You know how she likes to wander, talking to the exhibits – it may help her come to terms with … what has occurred.’

Miss Ursula’s eyes fell upon the empty grate by the armchair and gave a slight shudder as she stared at those cold ashes and cinders. ‘Not since that day when we first came upon the forest clearing have I known such distress.’

Chewing the inside of her cheek, Edie regarded the black-gowned woman and said, ‘Tell me about the Loom.’

The faintest of creases furrowed Miss Ursula’s forehead. ‘You already know everything. The Loom was made from the first bough hewn from the World Tree by the Lord of the Frost Giants.’

‘But what was it like?’ the child persisted.

Miss Ursula sank back into the chair. ‘There are no adequate words to explain,’ she said. ‘From the moment I set it in motion and the glittering threads ran through the warp, everything was enslaved, including myself. Many have cursed my name since that day, but had I balked at the deed, then the lords of the ice would have destroyed the last vestige of Yggdrasill, and the end would have come before there had barely been a beginning. What choice had I?’

Edie reached for a small, unglazed ceramic jar which fitted pleasantly in her palm, and toyed with the idea of popping the dead mouse inside it.

‘Was you scared?’ she asked, irked to find that the lid of the jar was stuck in place.

‘Terrified,’ Miss Ursula confessed. ‘I had taken it upon myself and my sisters to become Mistresses of Destiny. Yet I was exhilarated also, and when the first glimmering strands began to weave the untold history of the world, it was the most entrancing sight I had ever beheld, outshining even the spectacle of Askar beneath the dappling sky of the great ash’s leaves.’

Lifting her face to the ceiling, where deserted cobwebs festooned the chandelier, the old woman’s stern countenance melted.

‘What ravishing beauty the fabric of the Fates possessed,’ she murmured. ‘Every stitch was an unseen moment in time and the threads of life shone with an intensity according to the nature of who they belonged to. How that shimmering splendour captivated me and my sisters, and how easily we accepted our roles – even Veronica.

‘You cannot imagine how bewitching that tapestry became – a rippling expanse of colour and movement that burned with a light like no other. Patterns of joy and creation glowed within its fabric in an ever-shifting performance of lustrous delight.’

Rising from the seat, the woman fetched Edie’s woollen pixie hood down from the mantelpiece, where she had placed it to dry after washing the blood and dirt of the girl’s adventures from its fibres.

‘The glittering strands which course through this hood are an impoverished representation of the glorious wonders which were stretched upon the Loom. Yet the garment is a symbol of your bond with us, Edith dear. A joining of your life to that of Nirinel.’

Edie came to stand next to her. ‘Is it dry?’ she demanded. ‘Give it to me.’

The old woman placed the small pointed hood upon the girl’s head and, with a slender finger, traced the interwoven streaks of silver tinsel.

‘Celandine knitted this from a single thread taken from the patterns of our own woven doom,’ she explained. ‘Through it passes the unstoppable might of Destiny and your life is tied to it.’

‘What did the Loom look like?’ the child asked.

Miss Ursula walked across the room to where a damask curtain hung across a doorway. ‘Come, child,’ she instructed.

The old woman led the girl down the narrow flight of stairs which led to the third floor of The Wyrd Museum, only to pause when they reached halfway. A huge oil painting hung upon the near wall and Miss Ursula regarded it with satisfaction.

‘I remember that I was a trifle harsh with the artist when he delivered the work to me,’ she said. ‘I thought he had taken my description a little too literally but, on reflection, it is a fine enough depiction of those far off days.’

Edie stared dutifully at the great canvas.

The borders of a vast forest crowded the edges of the frame but, rearing from the ground in the centre, was a representation of a titanic ash tree. The figures of three young maidens stood about a wide pool by the roots. Edie guessed that they were supposed to be the Websters and she smiled to note that, even here, Miss Celandine was dancing.

‘I do not recall if I ever congratulated the artist on his capturing of my sisters,’ Miss Ursula muttered. ‘I know that I was irritated by the veil he had painted across my face. But, now that I look closely, that nymph robed in white is unmistakably Veronica. Perhaps he based this portrayal upon a lover, for surely there is an intensity there. An unbounded beauty and tenderness, more so than the others. Veronica was like that; none could outshine her.’

Lifting her hand, she pointed at the measuring rod in the figure’s hand. ‘There is her cane,’ she said regretfully. ‘Alas for its loss in the burning – it is another power gone from this place and I wish we still had it in our keeping.’

The old woman’s jaw tightened and an expression that was drenched in dread settled over her gaunt face. ‘I must not anticipate the days ahead,’ she cautioned herself. ‘The ordeal will be severe enough without wishing it any closer.’

‘But the Loom,’ Edie prompted.

Miss Ursula’s caressing hand travelled across the varnished oils to where violet shadows were cast over her own, younger counterpart and directed the girl’s scrutiny towards a large structure fashioned from great timbers.

‘There it is,’ she breathed. ‘That which yoked us all and made us slaves to the lives we were allotted.’

‘Don’t look much,’ Edie grumbled with disappointment.

Miss Ursula straightened. ‘I was deliberately vague in the description I presented to the artist,’ she explained. ‘There were certain … details I had reason to leave out. But, in essence, that is the controlling device which dominated us all.

‘The span and tale of all things were entwined in that cloth, Edith. Yet within its bitter beauty were also large, ugly patches of fathomless shadow, where hate and war were destined to occur. Sometimes those conflicts were bidden to prove so violent that the horror and cruelty fated to transpire in the world would rip and tear through the fabric, causing vicious rents to mar the surrounding pattern. Dangerous and ungovernable are those fissures in the web of Fate. Although we did our best to repair them – poor Celandine toiled so hard, so often – many lovely things and brave souls were lost forever within those hollow voids and there was naught we could do.’

‘I came from one of them,’ Edie chirped.

Miss Ursula inclined her head and bestowed one of her rare smiles upon the child. ‘Indeed you did, Edith,’ she said. ‘When war rages and the cloth rips wide, my sisters and I are blind. We could see nothing beneath the banner of death which obscured those years and so we missed you – the very one we had waited for all these years. Still, once we realised our error, we were able to perform a little belated repair and pluck you through it to join us.’

Her eyes still riveted upon the indistinct portrait of the Loom, Edie asked, ‘What happened to it?’

Miss Ursula smoothed out the creases of her taffeta gown. ‘I believe I told you before you went to Glastonbury, Edith. The Loom was broken many years ago and cannot be remade. The tapestry of the world’s destiny was never completed and thus our futures remain uncertain.’

Edie lowered her gaze and fiddled with the jar she still held in her hand. Miss Ursula seemed to forget her young charge and was following her own train of thought.

‘Without the Cloth of Doom to guide me, how can I be sure that the path I have chosen is the right one? Is there still time to turn back and steer away from this course? Too long have I spent foretelling the pages of the world to act blindfold now. Halt this, Ursula, you must.’

Not listening to her, Edie gave the lid another twist and at last the wretched jar was opened. Bringing it close to her face, the girl inspected the contents to see if there was room for a dead mouse inside. But a foul-smelling, ochre-coloured ointment filled the small vessel and she groaned inwardly at having unearthed yet more of Miss Veronica’s wrinkle cream.

At her side Miss Ursula looked up sharply as though she had heard something.

‘It is too late!’ she cried, expelling her indecision with a clap of her hands. ‘He is here! Come, Edith, the one I have sent for, our catalyst – he arrives. We must greet him.’

Edie had not heard anything, but she knew that the eldest of the Websters was more attuned to the vibrations of this mysterious building than herself.

As Miss Ursula descended the stairs, the girl hesitated. She gave the ointment within the jar one final sniff, then stuck out her tongue to lick it experimentally. Retching and coughing, the girl hurriedly followed Miss Ursula into the main part of the museum, shoving the jar into her pocket with the rest of her magpie finds.

Neil Chapman had slept deeply for a couple of hours, but woke suddenly at quarter-past-six. His little brother Josh was still fast asleep and Neil looked at his watch in disbelief. After all that had happened, after his complete exhaustion, he was now, unaccountably, wide awake and no amount of burying his head under the warm blankets could make him doze off again.

Climbing out of bed, he dragged on some clean clothes and crept out into the living room. To his relief, he found that his father was finally sleeping, and the boy silently left the apartment to look for Quoth.

He did not have to roam far to find him. The raven was roosting in The Fossil Room, which opened off from the passage. With his head tucked under one wing, the bird sat upon one of the display cabinets, making faint purling noises in his sleep. In fact, his slumber was so profound that Neil managed to walk straight up to him without the raven waking.

The boy did not have the heart to disturb his rest. Quoth looked so contented there, in his dim little corner, that he almost tiptoed away again.

At that moment, however, a sudden pounding resounded within the museum and the raven was startled awake. With his scruffy feathers askew and his head wiggling drunkenly up and down, the bird stretched open his beak and fixed his eye upon his surroundings.

‘Good morning,’ Neil greeted him.

‘Fie!’ Quoth squawked in alarm. ‘The hammers of the underworld doth strike! Alarum! Alarum!’

‘I think it’s just someone at the door,’ the boy chuckled.

The bird rubbed the sleep from his eye and stared at Neil with dozy happiness.

‘Squire Neil!’ he croaked, slithering across the glass in his haste to salute him. ‘The argent stars of heaven’s country are but barely snuffed in their daily dowsing, yet already thou art astir! Good morrow, good morrow, oh spurner of Morpheus!’

Neil laughed and stroked the bird’s featherless head. ‘I’m sorry about what happened last night,’ he apologised. ‘Were you okay out here?’

‘This lack-a-bed sparrow hath nested in more danksome grots than this.’

‘Once an idea gets into Dad’s head there’s nothing anyone can do,’ Neil explained. ‘With any luck he’ll have calmed down by tonight.’

Again the knocking sounded and Neil held out his arm for Quoth to climb up to his shoulder.

‘We’d better see who that is.’

‘Good tidings ne’er rose with the dawn,’ the raven warned in his ear.

Through the collections they hurried, until they came to the main hallway, and Neil pulled the great oaken door open. To his surprise, he found the Chief Inspector waiting upon the step.

‘What’s happened?’ the boy asked, instantly fearing the worst.

‘Nothing yet,’ Hargreaves reassured him. ‘I’ve come on an errand – Urdr commanded me.’

Neil peered past him and saw, standing in the alleyway, the fidgeting figure of Austen Pickering. The boy recognised him immediately. The pensioner had stopped him in the street after school a few days ago, and warned him of the dangers of living in The Wyrd Museum. Neil had not forgotten those forbidding words and it made him uneasy to see this little man again.

‘A plainer pudding this nidyard ne’er chanced to espy,’ Quoth reflected, regarding the man with his beady, yet critical, eye. ‘’Twas a poorly craft which didst shape yonder lumpen clay.’

The Chief Inspector coughed awkwardly but added in a whisper, ‘I brought him as soon as I received the message from Urdr. I was to bring Mr Pickering here. It’s not my place to ask why.’

‘But that’s the ghost hunter,’ Neil muttered. ‘I don’t understand. What can she want with him?’

‘If you would be civil enough to allow the gentleman inside,’ a clipped voice rang out from the hallway, ‘you might be able to learn.’

Neil turned and Quoth chirped morosely. Upon the stairs, looking as regal and supreme as any empress, Miss Ursula Webster stood gazing down on them. At her side, in contrast to the old woman’s tall, stately figure, Edie Dorkins looked like a Thames-scavenging mudlark. Her oval face was smudged with dirt, her clothes were torn and wide holes gaped in her woollen stockings.

Hargreaves lowered his eyes in reverence and bowed to both. ‘I have done what was asked of me—’

‘Is there an outbreak of deafness?’ Miss Ursula demanded. ‘I said for you to let the man inside!’

Hastily leaving the entrance steps, the Chief Inspector permitted Austen Pickering to take his place, and Neil looked at him keenly.