Полная версия

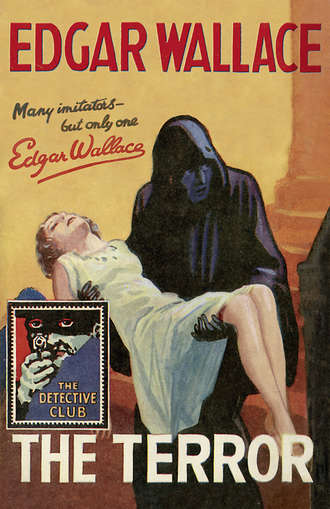

The Terror

‘Do you hear?’ she asked again.

‘The sound of feet shuffling on stones, and—my God, what’s that?’

It was the sound of knocking, heavy and persistent.

‘Somebody is at the door,’ she whispered, white to the lips.

Redmayne opened a drawer and took out something which he slipped into the pocket of his dressing-gown.

‘Go up to your room,’ he said.

He passed through the darkened lounge, stopped to switch on a light, and, as he did so, Cotton appeared from the servants’ quarters. He was fully dressed.

‘What is that?’ asked Redmayne.

‘Someone at the door, I think. Shall I open it?’

For a second the colonel hesitated.

‘Yes,’ he said at last.

Cotton took off the chain, and, turning the key, jerked the door open. A lank figure stood on the doorstep; a figure that swayed uneasily.

‘Sorry to disturb you.’ Ferdie Fane, his coat drenched and soaking, lurched into the room. He stared from one to the other. ‘I’m the second visitor you’ve had tonight.’

‘What do you want?’ asked Redmayne.

In a queer, indefinable way the sight of this contemptible man gave him a certain amount of relief.

‘They’ve turned me out of the Red Lion.’ Ferdie’s glassy eyes were fixed on him. ‘I want to stay here.’

‘Let him stay, Daddy.’

Redmayne turned; it was the girl.

‘Please let him stay. He can sleep in number seven.’

A slow smile dawned on Mr Fane’s good-looking face.

‘Thanks for invitation,’ he said, ‘which is accepted.’

She looked at him in wonder. The rain had soaked his coat, and, as he stood, the drops were dripping from it, forming pools on the floor. He must have been out in the storm for hours—where had he been? And he was strangely untalkative; allowed himself to be led away by Cotton to room No. 7, which was in the farther wing. Mary’s own pretty little bedroom was above the lounge. After taking leave of her father, she locked and bolted the door of her room, slowly undressed and went to bed. Her mind was too much alive to make sleep possible, and she turned from side to side restlessly.

She was dozing off when she heard a sound and sat up in bed. The wind was shrieking round the corners of the house, the patter of the rain came fitfully against her window, but that had not wakened her up. It was the sound of low voices in the room below. She thought she heard Cotton—or was it her father? They both had the same deep tone.

Then she heard a sound which made her blood freeze—a maniacal burst of laughter from the room below. For a second she sat paralysed, and then, springing out of bed, she seized her dressing-gown and went pattering down the stairs, and she saw over the banisters a figure moving in the hall below.

‘Who is that?’

‘It’s all right, my dear.’

It was her father. His room adjoined his study on the ground floor.

‘Did you hear anything, Daddy?’

‘Nothing—nothing,’ he said harshly, ‘Go to bed.’

But Mary Redmayne was not deficient in courage.

‘I will not go to bed,’ she said, and came down the stairs. ‘There was somebody in the lounge—I heard them,’ Her hand was on the lounge door when he gripped her arm.

‘For God’s sake, Mary, don’t go in!’ She shook him off impatiently, and threw open the door.

No light burned; she reached out for the switch and turned it. For a second she saw nothing, and then—

Sprawling in the middle of the room lay the body of a man, a terrifying grin on his dead face.

It was the tinker, the man who had quarrelled with Ferdie Fane that morning—the man whom Fane had threatened!

CHAPTER VIII

SUPERINTENDENT HALLICK came down by car with his photographer and assistants, saw the body with the local chief of police, and instantly recognised the dead man.

Connor! Connor, the convict, who said he would follow O’Shea to the end of the world—dead, with his neck broken, in that neat way which was O’Shea’s speciality.

One by one Hallick interviewed the guests and the servants. Cotton was voluble; he remembered the man, but had no idea how he came into the room. The doors were locked and barred, none of the windows had been forced. Goodman apparently was a heavy sleeper and lived in the distant wing. Mrs Elvery was full of theories and clues, but singularly deficient in information.

‘Fane—who is Fane?’ asked Hallick.

Cotton explained Mr Fane’s peculiar position and the hour of his arrival.

‘I’ll see him later. You have another guest on the books?’ He turned the pages of the visitors’ ledger.

‘He doesn’t come till today. He’s a parson, sir,’ said Cotton.

Hallick scrutinised the ill-favoured face.

‘Have I seen you before?’

‘Not me, sir.’ Cotton was pardonably agitated.

‘Humph!’ said Hallick. ‘That will do. I’ll see Miss Redmayne.’

Goodman was in the room and now came forward.

‘I hope you are not going to bother Miss Redmayne, superintendent. She is an extremely nice girl. I may say I am—fond of her. If I were a younger man—’ He smiled. ‘You see, even tea merchants have their romances.’

‘And detectives,’ said Hallick dryly. He looked at Mr Goodman with a new interest. He had betrayed from this middle-aged man a romance which none suspected. Goodman was in love with the girl and had probably concealed the fact from everybody in the house.

‘I suppose you think I am a sentimental jackass—’

Hallick shook his head.

‘Being in love isn’t a crime, Mr Goodman,’ he said quietly.

Goodman pursed his lips thoughtfully. ‘I suppose it isn’t—imbecility isn’t a crime, anyway,’ he said.

He was going in the direction whence Mary would come, when Hallick stopped him, and obediently the favoured guest shuffled out of another door.

Mary had been waiting for the summons, and her heart was cold within her as she followed the detective to Hallick’s presence. She had not seen him before and was agreeably surprised. She had expected a hectoring, bullying police officer and found a very stout and genial man with a kindly face. He was talking to Cotton when she came in, and for a moment he took no notice of her.

‘You’re sure you’ve no idea how this man got in last night?’

‘No, sir,’ said Cotton.

‘No window was forced, the door was locked and bolted, wasn’t it?’

Cotton nodded.

‘I never let him in,’ he said.

Hallick’s eyelids narrowed.

‘Twice you’ve said that. When I arrived this morning you volunteered the same statement. You also said you passed Mr Fane’s room on your way in, that the door was open and the room was empty.’

Cotton nodded.

‘You also said that the man who rung up the police and gave the name of Cotton was not you.’

‘That’s true, sir.’

It was then that the detective became aware of the girl’s presence and signalled Cotton to leave the room.

‘Now, Miss Redmayne; you didn’t see this man, I suppose?’

‘Only for a moment.’

‘Did you recognise him?’

She nodded.

Hallick looked down at the floor, considering.

‘Where do you sleep?’ he asked.

‘In the room above this hall.’

She was aware that the second detective was writing down all that she said.

‘You must have heard something—the sound of a struggle—a cry?’ suggested Hallick, and, when she shook her head: ‘Do you know what time the murder occurred?’

‘My father said it was about one o’clock.’

‘You were in bed? Where was your father—anywhere near this room?’

‘No.’ Her tone was emphatic.

‘Why are you so sure?’ he asked keenly.

‘Because when I heard the door close—’

‘Which door?’ quickly.

He confused her for a moment.

‘This door.’ She pointed to the entrance of the lounge. ‘Then I looked over the landing and saw my father in the passage.’

‘Yes. He was coming from or going to this room. How was he dressed?’

‘I didn’t see him,’ she answered desperately. ‘There was no light in the passage. I’m not even certain that it was his door.’

Hallick smiled.

‘Don’t get rattled, Miss Redmayne. This man, Connor, was a well-known burglar; it is quite possible that your father might have tackled him and accidentally killed him. I mean, such a thing might occur.’

Mary shook her head.

‘You don’t think that happened? You don’t think that he got frightened when he found the man was dead, and said he knew nothing about it?’

‘No,’ she said.

‘You heard nothing last night of a terrifying or startling nature?’

She did not answer.

‘Have you ever seen anything at Monkshall?’

‘It was all imagination,’ she said in a low voice; ‘but once I thought I saw a figure on the lawn—a figure in the robes of a monk.’

‘A ghost, in fact?’ he smiled, and she nodded.

‘You see, I’m rather nervous,’ she went on. ‘I imagine things. Sometimes when I’ve been in my room I’ve heard the sound of feet moving here—and the sound of an organ.’

‘Does the noise seem distinct?’

‘Yes. You see, the floor isn’t very thick.’

‘I see,’ he said dryly. ‘And yet you heard no struggle last night? Come, come, Miss Redmayne, try to remember.’

She was in a panic.

‘I don’t remember anything—I heard nothing.’

‘Nothing at all?’ He was gently insistent. ‘I mean, the man must have fallen with a terrific thud. It would have wakened you if you had been asleep—and you weren’t asleep. Come now, Miss Redmayne. I think you’re making a mystery of nothing. You were terribly frightened by this monk you saw, or thought you saw, and your nerves were all jagged. You heard a sound and opened your door, and your father’s voice said “It’s all right”, or something like that. Isn’t that what occurred?’

He was so kindly that she was deceived. ‘Yes.’

‘He was in his dressing-gown, I suppose—ready for bed?’

‘Yes,’ she said again.

He nodded.

‘Just now you told me you didn’t see him—that there was no light in the passage!’

She sprang up and confronted him.

‘You’re trying to catch me out. I won’t answer you. I heard nothing, I saw nothing. My father was never in this room—it wasn’t his voice—’

‘My voice, old son!’

Hallick turned quickly. A smiling man was standing in the doorway.

‘How d’ye do? My name’s Fane—Ferdie Fane. How’s the late departed?’

‘Fane, eh?’ Hallick was interested in this lank man.

‘My voice, old son,’ said Fane again. ‘Indeed!’ Then the detective did an unaccountable thing. He broke off the cross-examination, and, beckoning his assistant, the two men went out of the room together.

Mary stared at the new boarder wonderingly.

‘It was not your voice,’ she said. ‘Why did you say it was? Can’t you see that they are suspecting everybody? Are you mad? They will think you and I are in collusion.’

He beamed at her.

‘C’lusion’s a good word. I can say that quite distinctly, but it’s a good word.’

She went to the door and looked out. Hallick and his assistant were in earnest consultation on the lawn, and her heart sank.

Fane was helping himself to a whisky when she returned to him.

‘They’ll come back soon, and then what questions will they ask me? Oh, I wish you were somebody I could talk to, somebody I could ask to help! It’s so horrible to see a man like you—a drunken weakling.’

‘Don’t call me names,’ he said severely. ‘You ought to be ashamed of yourself. Tell me anything you like.’

If only she could!

It was Cotton who interrupted her confidence. He came in that sly, furtive way of his.

‘The new boarder’s arrived, miss—the parson gentleman,’ he said, and stood aside to allow the newcomer to enter the lounge.

It was a slim and aged clergyman, white-haired, bespectacled. His tone was gentle, a little unctuous perhaps; his manner that of a man who lavished friendliness.

‘Have I the pleasure of speaking to dear Miss Redmayne? I am the Reverend Ernest Partridge. I’ve had to walk up. I thought I was to be met at the station.’

He gave her a limp hand to shake.

The last thing in the world she craved at that moment was the distraction of a new boarder. ‘I’m very sorry, Mr Partridge—we are all rather upset this morning. Cotton, take the bag to number three.’

Mr Partridge was mildly shocked.

‘Upset? I hope that no untoward incident has marred the perfect beauty of this wonderful spot?’

‘My father will tell you all about it. This is Mr Fane.’

She had to force herself to this act of common politeness.

At this moment Hallick came in hurriedly.

‘Have you any actors in the grounds, Miss Redmayne?’ he asked quickly.

‘Actors?’ She stared at him.

‘Anybody dressed up.’ He was impatient. ‘Film actors—they come to these old places. My man tells me he’s just seen a man in a black habit come out of the monk’s tomb—he had a rifle in his hand. By God, there he is!’

He pointed through the lawn window, and at that moment Mary felt a pair of strong arms clasped about her, and she was swung round. It was Fane who held her, and she struggled, speechless with indignation. And then—

‘Ping!’

The staccato crack of a rifle, and a bullet zipped past her and smashed the mirror above the fireplace. So close it came that she thought at first it had struck her, and in that fractional space of time realised that only Ferdinand Fane’s embrace had saved her life.

CHAPTER IX

HALLICK, after an extensive search of the grounds which produced no other clue than an expended cartridge case, went up to town, leaving Sergeant Dobie in charge.

Mary never distinctly remembered how that dreadful day dragged to its end. The presence of the Scotland Yard man in the house gave her a little confidence, though it seemed to irritate her father. Happily, the detective kept himself unobtrusively in the background.

The two people who seemed unaffected by the drama of the morning were Mr Fane and the new clerical boarder. He was a loquacious man, primed with all kinds of uninteresting anecdotes; but Mrs Elvery found him a fascinating relief.

Ferdie Fane puzzled Mary. There was so much about him that she liked, and, but for this horrid tippling practice of his she might have liked him more—how much more she did not dare admit to herself. He alone remained completely unperturbed by that shot which had nearly ended her life and his.

In the afternoon she had a little talk with him and found him singularly coherent.

‘Shooting at me? Good Lord, no!’ He scoffed. ‘It must have been a Nonconformist—we High Church parsons have all sorts of enemies.’

‘Have you?’ she asked quietly, and there was an odd look in his eyes when he answered:

‘Maybe. There are quite a number of people who want to get even with me for my past misdeeds.’

‘Mrs Elvery said they were going to send Bradley down.’

‘Bradley!’ he said contemptuously. ‘That back number at Scotland Yard!’ And then, as though he could read her thoughts, he asked quickly: ‘Did that interesting old lady say anything else?’

They were walking through the long avenue of elms that stretched down to the main gates of the park. Two days ago she would have fled from him, but now she found a strange comfort in his society. She could not understand herself; found it equally difficult to recover a sense of her old aversion.

‘Mrs Elvery’s a criminologist.’ She smiled whimsically, though she never felt less like smiling in her life. ‘She keeps press cuttings of all the horrors of the past years, and she says she’s sure that that poor man Connor was connected with a big gold robbery during the war. She said there was a man named O’Shea in it—’

‘O’Shea?’ said Fane quickly, and she saw his face change. ‘What the devil is she talking about O’Shea for? She had better be careful—I beg your pardon.’ He was all smiles again.

‘Have you heard of him?’

‘The merest rumour,’ he said almost gaily. ‘Tell me what Mrs Elvery said.’

‘She said that a lot of gold disappeared and was buried somewhere, and she’s got a theory that it was buried in Monkshall or in the grounds; that Connor was looking for it, and that he got Cotton, the butler, to let him in—that’s how he came to be in the house. I heard her telling Mr Partridge the story. She doesn’t like me well enough to tell me.’ They paced in silence for a while.

‘Do you like him—Partridge, I mean?’ asked Ferdie.

She thought he was very nice.

‘That means he bores you.’ He chuckled softly to himself. And then: ‘Why don’t you go up to town?’

She stopped dead and stared at him.

‘Leave Monkshall? Why?’

He looked at her steadily.

‘I don’t think Monkshall is very healthy; in fact, it’s a little dangerous.’

‘To me?’ she said incredulously, and he nodded.

‘To you, in spite of the fact that there are people living at Monkshall who adore you, who would probably give their own lives to save you from hurt.’

‘You mean my father?’ She tried to pass off what might easily develop into an embarrassing conversation.

‘I mean two people—for example, Mr Goodman.’

At first she was inclined to be angry and then she laughed.

‘How absurd! Mr Goodman is old enough to be my father.’

‘And young enough to love you,’ said Fane quietly. ‘That middle-aged gentleman is genuinely fond of you, Miss Redmayne. There is one who is not so middle-aged who is equally fond of you—’

‘In sober moments?’ she challenged.

And then Mary thought it expedient to remember an engagement she had in the house. He did not attempt to stop her. They walked back towards Monkshall a little more quickly.

Inspector Hallick went back to London a very puzzled man, though he was not as hopelessly baffled as his immediate subordinates thought. He was satisfied in his mind that behind the mystery of Monkshall was the more definite mystery of O’Shea.

When he reached his office he rang for his clerk, and when the officer appeared:

‘Get me the record of the O’Shea gold robbery, will you?’ he said. ‘And data of any kind we have about O’Shea.’

It was not the first time he had made the last request and the response had been more or less valueless, but the Record Department of Scotland Yard had a trick of securing new evidence from day to day from unexpected sources. The sordid life histories that were compiled in that business-like room touched life at many points; the political branch that dealt with foreign anarchists had once exposed the biggest plot of modern times through a chance remark made by an old woman arrested for begging.

When the clerk had gone Hallick opened his notebook and jotted down the meagre facts he had compiled. Undoubtedly the shot had been fired from the ruins which, he discovered, were those of an old chapel in the grounds, now covered with ivy and almost hidden by sturdy chestnut trees. How the assassin had made his escape was a mystery. He did not preclude the possibility that some of these wizened slabs of stone hidden under thickets of elderberry and hawthorn trees might conceal the entrance to an underground passage.

He offered that solution to one of the inspectors who strolled in to gossip. It was the famous Inspector Elk, saturnine and sceptical.

‘Underground passages!’ scoffed Elk. ‘Why, that’s the last resource, or resort—I am not certain which—of the novel writer. Underground passages and secret panels! I never pick up a book which isn’t full of ’em!’

‘I don’t rule out either possibility,’ said Hallick quietly. ‘Monkshall was one of the oldest inhabited buildings in England. I looked it up in the library. It flourished even in the days of Elizabeth—’

Elk groaned.

‘That woman! There’s nothing we didn’t have in her days!’

Inspector Elk had a genuine grievance against Queen Elizabeth; for years he had sought to pass an education test which would have secured him promotion, but always it was the reign of the virgin queen and the many unrememberable incidents which, from his point of view, disfigured that reign, that had brought about his undoing.

‘She would have secret panels and underground passages!’

And then a thought struck Hallick.

‘Sit down, Elk,’ he said. ‘I want to ask you something.’

‘If it’s history save yourself the trouble. I know no more about that woman except that she was not in any way a virgin. Whoever started this silly idea about the Virgin Queen?’

‘Have you ever met O’Shea?’ asked Hallick.

Elk stared at him.

‘O’Shea—the bank smasher? No, I never met him. He is in America, isn’t he?’

‘I think he is very much in England,’ said Hallick, and the other man shook his head.

‘I doubt it.’ Then after a moment’s thought: ‘There’s no reason why he should be in England. I am only going on the fact that he has been very quiet these years, but then a man who made the money he did can afford to sit quiet. As a rule, a crook who gets money takes it to the nearest spieling club and does it in, and as he is a natural lunatic—’

‘How do you know that?’ asked Hallick sharply.

Before he answered, Elk took a ragged cigar from his pocket and lit it.

‘O’Shea is a madman,’ he said deliberately. ‘It is one of the facts that is not disputed.’

‘One of the facts that I knew nothing about till I interviewed old Connor in prison, and I don’t remember that I put it on record,’ said Hallick. ‘How did you know?’

Elk had an explanation which was new to his superior.

‘I went into the case years ago. We could never get O’Shea or any particulars about him except a scrap of his writing. I am talking about the days before the gold robbery and before you came into the case. I was just a plain detective officer at the time and if I couldn’t get his picture and his fingerprints I got on to his family. His father died in a lunatic asylum, his sister committed suicide, his grandfather was a homicide who died whilst he was awaiting his trial for murder. I’ve often wondered why one of these clever fellows didn’t write a history of the family.’

This was indeed news to John Hallick, but it tallied with the information that Connor had given to him.

The clerk came back at this moment with a formidable dossier and one thin folder. The contents of the latter showed the inspector that nothing further had been added to the sketchy details he had read before concerning O’Shea. Elk watched him curiously.

‘Refreshing your mind about the gold robbery? Doesn’t it make your mouth water to think that all these golden sovereigns are hidden somewhere. Pity Bradley isn’t on this job. He knows the case like I know the back of my hand, and if you think this murder has got anything to do with O’Shea, I’d cable him to come back if I were you.’

Hallick was turning the pages of the typewritten sheets slowly.

‘As far as Connor is concerned, he only got what was coming to him. He squealed a lot at the time of his conviction about being double-crossed, but Connor double-crossed more crooks than any man on the records, and Soapy Marks. I happened to know both of them. They were quite prepared to squeak about O’Shea just before the gold robbery. Where is Soapy?’

Hallick shook his head and closed the folder.

‘I don’t know. I wish you would put the word round to the divisions that I’d like to see Soapy Marks,’ he said. ‘He usually hangs out in Hammersmith, and I should like to give him a word of warning.’

Elk grinned.

‘You couldn’t warn Soapy,’ he said. ‘He knows too much. Soapy is so clever that one of these days we’ll find him at Oxford or Cambridge. Personally,’ he ruminated reflectively, ‘I prefer clever crooks. They don’t take much catching; they catch themselves.’

‘I am not worrying about his catching himself,’ said Hallick. ‘But I am a little anxious as to whether O’Shea will catch him first. That is by no means outside the bounds of possibility.’