Полная версия

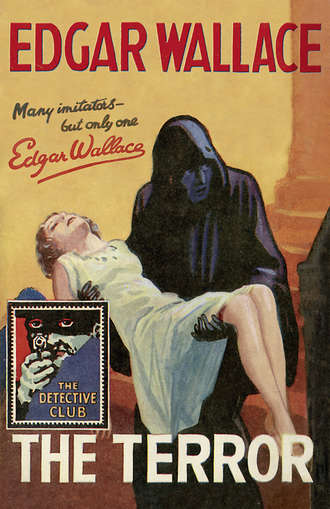

The Terror

‘Well, I haven’t objected so far, have I?’ he smiled.

‘I suppose I’m naturally romantic,’ she said. ‘I see mystery in almost everything. Even you are mysterious.’ And, when he looked alarmed: ‘Oh, I don’t mean sinister!’

He was glad she did not.

‘But Colonel Redmayne is sinister,’ she said emphatically.

He considered this.

‘He never struck me that way,’ he said slowly.

‘But he is,’ she persisted. ‘Why did he buy this place miles from everywhere and turn it into a boarding house?’

‘To make money, I suppose.’

She smiled triumphantly and shook her head.

‘But he doesn’t. Mamma says that he must lose an awful lot of money. Monkshall is very beautiful, but it has got an awful reputation. You know that it is haunted, don’t you?’

He laughed good-naturedly at this. Mr Goodman was an old boarder and had heard this story before.

‘I’ve heard things and seen things. Mamma says that there must have been a terrible crime committed here. It is!’ She was more emphatic.

Mr Goodman thought that her mother let her mind dwell too much on murders and crimes. For the stout and fussy Mrs Elvery wallowed in the latest tragedies which filled the columns of the Sunday newspapers.

‘She does love a good murder,’ agreed Veronica. ‘We had to put off our trip to Switzerland last year because of the River Bicycle Mystery. Do you think Colonel Redmayne ever committed a murder?’

‘What a perfectly awful thing to say!’ said her shocked audience.

‘Why is he so nervous?’ asked Veronica intensely. ‘What is he afraid of? He is always refusing boarders. He refused that nice young man who came yesterday.’

‘Well, we’ve got a new boarder coming tomorrow,’ said Goodman, finding his newspaper again.

‘A parson!’ said Veronica contemptuously. ‘Everybody knows that parsons have no money.’

He could chuckle at this innocent revelation of Veronica’s mind.

‘The colonel could make this place pay, but he won’t.’ She grew confidential. ‘And I’ll tell you something more. Mamma knew Colonel Redmayne before he bought this place. He got into terrible trouble over some money—Mamma doesn’t exactly know what it was. But he had no money at all. How did he buy this house?’

Mr Goodman beamed.

‘Now that I happen to know all about! He came into a legacy.’

Veronica was disappointed and made no effort to hide the fact. What comment she might have offered was silenced by the arrival of her mother.

Not that Mrs Elvery ever ‘arrived’. She bustled or exploded into a room, according to the measure of her exuberance. She came straight across to the settee where Mr Goodman was unfolding his paper again.

‘Did you hear anything last night?’ she asked dramatically.

He nodded.

‘Somebody in the next room to me was snoring like the devil,’ he began.

‘I occupy the next room to you, Mr Goodman,’ said the lady icily. ‘Did you hear a shriek?’

‘Shriek?’ He was startled.

‘And I heard the organ again last night!’

Goodman sighed.

‘Fortunately I am a little deaf. I never hear any organs or shrieks. The only thing I can hear distinctly is the dinner gong.’

‘There is a mystery here.’ Mrs Elvery was even more intense than her daughter. ‘I saw that the day I came. Originally I intended staying a week; now I remain here until the mystery is solved.’

He smiled good-humouredly.

‘You’re a permanent fixture, Mrs Elvery.’

‘It rather reminds me,’ Mrs Elvery recited rapidly, but with evident relish, ‘of Pangleton Abbey, where John Roehampton cut the throats of his three nieces, aged respectively, nineteen, twenty-two and twenty-four, afterwards burying them in cement, for which crime he was executed at Exeter Gaol. He had to be supported to the scaffold, and left a full confession admitting his guilt!’

Mr Goodman rose hastily to fly from the gruesome recital. Happily, rescue came in the shape of the tall, soldierly person of Colonel Redmayne. He was a man of fifty-five, rather nervous and absent of manner and address. His attire was careless and somewhat slovenly. Goodman had seen this carelessness of appearance grow from day to day.

The colonel looked from one to the other.

‘Good-morning. Is everything all right?’

‘Comparatively, I think,’ said Goodman with a smile. He hoped that Mrs Elvery would find another topic of conversation, but she was not to be denied.

‘Colonel, did you hear anything in the night?’

‘Hear anything?’ he frowned. ‘What was there to hear?’

She ticked off the events of the night on her podgy fingers.

‘First of all the organ, and then a most awful, blood-curdling shriek. It came from the grounds—from the direction of the Monk’s Tomb.’

She waited, but he shook his head.

‘No, I heard nothing. I was asleep,’ he said in a low voice.

Veronica, an interested listener, broke in.

‘Oh, what a fib! I saw your light burning long after Mamma and I heard the noise. I can see your room by looking out of my window.’

He scowled at her.

‘Can you? I went to sleep with the light on. Has anyone seen Mary?’

Goodman pointed across the park.

‘I saw her half an hour ago,’ he said.

Colonel Redmayne stood hesitating, then, without a word, strode from the room, and they watched him crossing the park with long strides.

‘There’s a mystery here!’ Mrs Elvery drew a long breath. ‘He’s mad. Mr Goodman, do you know that awfully nice-looking man who came yesterday morning? He wanted a room, and when I asked the colonel why he didn’t let him stay he turned on me like a fiend! Said he was not the kind of man he wanted to have in the house; said he dared—“dared” was the word he used—to try to scrape acquaintance with his daughter, and that he didn’t want any good-for-nothing drunkards under the same roof.’

‘In fact,’ said Mr Goodman, ‘he was annoyed! You mustn’t take the colonel too seriously—he’s a little upset this morning.’

He took up the letters that had come to him by the morning post and began to open them.

‘The airs he gives himself!’ she went on. ‘And his daughter is no better. I must say it, Mr Goodman. It may sound awfully uncharitable, but she’s got just as much—’ She hesitated.

‘Swank?’ suggested Veronica, and her mother was shocked. ‘It’s a common expression,’ said Veronica.

‘But we aren’t common people,’ protested Mrs Elvery. ‘You may say that she gives herself airs. She certainly does. And her manners are deplorable. I was telling her the other day about the Grange Road murder. You remember, the man who poisoned his mother-in-law to get the insurance money—a most interesting case—when she simply turned her back on me and said she wasn’t interested in horrors.’

Cotton, the butler, came in at that moment with the mail. He was a gloomy man who seldom spoke. He was leaving the room when Mrs Elvery called him back.

‘Did you hear any noise last night, Cotton?’

He turned sourly.

‘No, ma’am. I don’t get a long time to sleep—you couldn’t wake me with a gun.’

‘Didn’t you hear the organ?’ she insisted.

‘I never hear anything.’

‘I think the man’s a fool,’ said the exasperated lady.

‘I think so too, ma’am,’ agreed Cotton, and went out.

CHAPTER VI

MARY went to the village that morning to buy a week’s supply of stamps. She barely noticed the young man in plus-fours who sat on a bench outside the Red Lion, though she was conscious of his presence; conscious, too, of the stories she had heard about him.

She had ceased being sorry for him. He was the type of man, she decided, who had gone over the margin of redemption; and, besides, she was annoyed with him because he had irritated her father, for Mr Ferdie Fane had had the temerity to apply for lodging at Monkshall.

Until that morning she had never spoken to him, nor had she any idea that such a misfortune would overtake her, until she came back through the village and turned into the little lane whence ran a footpath across Monkshall Park.

He was sitting on a stile, his long hands tightly clasped between his knees, a drooping cigarette in his mouth, gazing mournfully through his horn-rimmed spectacles into vacancy. She stood for a moment, thinking he had not seen her, and hesitating whether she should take a more round-about route in order to avoid him. At that moment he got down lazily, took off his cap with a flourish.

‘Pass, friend; all’s well,’ he said.

He had rather a delightful smile, she noticed, but at the moment she was far from being delighted.

‘If I accompany you to your ancestral home, does your revered father take a gun or loose a dog?’

She faced him squarely.

‘You’re Mr Fane, aren’t you?’

He bowed; the gesture was a little extravagant, and she went hot at his impertinence.

‘I think in the circumstances, Mr Fane, it is hardly the act of a gentleman to attempt to get into conversation with me.’

‘It may not be the act of a gentleman, but it is the act of an intelligent human being who loves all that is lovely,’ he smiled. ‘Have you ever noticed how few really pleasant-looking people there are in the world? I once stood at the corner of a street—’

‘At present you’re standing in my way,’ she interrupted him.

She was not feeling at her best that morning; her nerves were tense and on edge. She had spent a night of terror, listening to strange whispers, to sounds that made her go cold, to that booming note of a distant organ which made her head tingle. Otherwise, she might have handled the situation more commandingly. And she had seen something, too—something she had never seen before; a wild, mouthing shape that had darted across the lawn under her window and had vanished.

He was looking at her keenly, this man who swayed slightly on his feet.

‘Does your father love you?’ he asked, in a gentle, caressing tone.

She was too startled to answer.

‘If he does he can refuse you nothing, my dear Miss Redmayne. If you said to him, “Here is a young man who requires board and lodging”—’

‘Will you let me pass, please?’ She was trembling with anger.

Again he stepped aside with elaborate courtesy, and without a word she stepped over the stile, feeling singularly undignified. She was half-way across the park before she looked back. To her indignation, he was following, at a respectful distance, it was true, but undoubtedly following.

Neither saw the other unwanted visitor. He had arrived soon after Mrs Elvery and Goodman had gone out with their golf clubs to practise putting on the smooth lawn to the south of the house. He was a rough looking man, with a leather apron, and carried under his arm a number of broken umbrellas. He did not go to the kitchen, but after making a stealthy reconnaissance, had passed round to the lawn and was standing in the open doorway, watching Cotton as he gathered up the debris which the poetess had left behind.

Cotton was suddenly aware of the newcomer and jerked his head round.

‘Hallo, what do you want?’ he asked roughly.

‘Got any umbrellas or chairs to mend—any old kettles or pans?’ asked the man mechanically.

Cotton pointed in his lordliest manner. ‘Outside! Who let you in?’

‘The lodge-keeper said you wanted something mended,’ growled the tinker.

‘Couldn’t you come to the service door? Hop it.’

But the man did not move.

‘Who lives here?’ he asked.

‘Colonel Redmayne, if you want to know—and the kitchen door is round the corner. Don’t argue!’

The tinker looked over the room with approval.

‘Pretty snug place this, eh?’

Mr Cotton’s sallow face grew red.

‘Can’t you understand plain English? The kitchen door’s round the corner. If you don’t want to go there, push off!’

Instead, the man came farther into the room.

‘How long has he been living here—this feller you call Redmayne?’

‘Ten years,’ said the exasperated butler. ‘Is that all you want to know? You don’t know how near to trouble you are.’

‘Ten years, eh?’ The man nodded. ‘I want to see this colonel.’

‘I’ll give you an introduction to him,’ said Cotton sarcastically. ‘He loves tinkers!’

It was then that Mary came in breathlessly.

‘Will you send that young man away?’ She pointed to the oncoming Ferdie; for the moment she did not see the tinker.

‘Young man, miss?’ Cotton went to the window, ‘Why, it’s the gent who came yesterday—a very nice young gentleman he is, too.’

‘I don’t care who he is or what he is,’ she said angrily. ‘He is to be sent away.’

‘Can I be of any help, miss?’

She was startled to see the tinker, and looked from him to the butler.

‘No, you can’t,’ snapped Cotton.

‘Who are you?’ asked Mary.

‘Just a tinker, miss.’ He was eyeing her thoughtfully, and something in his gaze frightened her.

‘He—he came in here, and I told him to go to the kitchen,’ explained Cotton in a flurry. ‘If you hadn’t come he’d have been chucked out!’

‘I don’t care who he is—he must help you to get rid of this wretched young man,’ said Mary desperately. ‘He—’

She became suddenly dumb. Mr Ferdinand Fane was surveying her from the open window.

‘How d’ye do, everybody? Comment ça va?’

‘How dare you follow me!’ She stamped her foot in her fury, but he was unperturbed.

‘You told me to keep out of your sight, so I walked behind. It’s all perfectly clear.’

It would have been dignified to have left the room in silence—he had the curious faculty of compelling her to be undignified.

‘Don’t you understand that your presence is objectionable to me and to my father? We don’t want you here. We don’t wish to know you.’

‘You don’t know me.’ He was hurt. ‘I’ll bet you don’t even know that my Christian name is Ferdie.’

‘You’ve tried to force your acquaintance on me, and I’ve told you plainly that I have no desire to know you—’

‘I wan’ to stay here,’ he interrupted. ‘Why shouldn’t I?’

‘You don’t need a room here—you have a room at the Red Lion, and it seems a very appropriate lodging.’

It was then that the watchful tinker took a hand.

‘Look here, governor, this lady doesn’t want you here—get out.’

But he was ignored.

‘I’m not going back to the Red Lion,’ said Mr Fane gravely. ‘I don’t like the beer—I can see through it—’

A hand dropped on his shoulder.

‘Are you going quietly?’

Mr Fane looked round into the tinker’s face.

‘Don’t do that, old boy—that’s rude. Never be rude, old boy. The presence of a lady—’

‘Come on,’ began the tinker.

And then a hand like a steel vice gripped his wrist; he was swung from his feet and fell to the floor with a crash.

‘Ju-juishoo,’ said Mr Fane very gently.

He heard an angry exclamation and turned to face Colonel Redmayne.

‘What is the meaning of this?’

He heard his daughter’s incoherent explanation.

‘Take that man to the kitchen,’ he said. When they were gone: ‘Now, sir, what do you want?’

Her father’s tone was milder than Mary had expected.

‘Food an’ comfort for man an’ beast,’ said the younger man coolly, and with an effort the colonel restrained his temper.

‘You can’t stay here—I told you that yesterday. I’ve no room for you, and I don’t want you.’

He nodded to the door, and Mary left hurriedly. Now his voice changed.

‘Do you think I’d let you contaminate this house? A drunken beast without a sense of chivalry or decency—with nothing to do with his money but spend it in drink?’

‘I thought you might,’ said Ferdie.

A touch of the bell brought Cotton.

‘Show this—gentleman out of the house—and well off the estate,’ he said.

It looked as though his visitor would prove truculent, but to his relief Mr Fane obeyed, waving aside the butler’s escort.

He had left the house when a man stepped from the cover of a clump of bushes and barred his way. It was the tinker. For a few seconds they looked at one another in silence.

‘There’s only one man who could ever put that grip on me, and I want to have a look at you,’ said the tinker.

He peered into the immobile face of Ferdie Fane, and then stepped back.

‘God! It is you! I haven’t seen you for ten years, and I wouldn’t have known you but for that grip!’ he breathed.

‘I wear very well.’ There was no slur in the voice of Fane now. Every sentence rang like steel. ‘You’ve seen a great deal more than you ought to have seen, Mr Connor!’

‘I’m not afraid of you!’ growled the man. ‘Don’t try to scare me. The old trick, eh? Made up like a boozy mug!’

‘Connor, I’m going to give you a chance for your life.’ Fane spoke slowly and deliberately. ‘Get away from this place as quickly as you can. If you’re here tonight, you’re a dead man!’ Neither saw the girl who, from a window above, had watched—and heard.

CHAPTER VII

MRS ELVERY described herself as an observant woman. Less charitable people complained bitterly of her spying. Cotton disliked her most intensely for that reason, and had a special grievance by reason of the fact that she had surprised him that afternoon when he was deeply engaged in conversation with a certain tinker who had called that morning, and who now held him fascinated by stories of immense wealth that might be stored within the cellars and vaults of Monkshall.

She came with her news to Colonel Redmayne, and found that gentleman a little dazed and certainly apathetic. He had got into the habit of retiring to his small study and locking the door. There was a cupboard there, just big enough for a bottle and two glasses, handy enough to hide them away when somebody knocked.

He was not favourably disposed towards Mrs Elvery, and this may have been the reason why he gave such scant attention to her story.

‘He’s like a bear, my dear,’ said that good lady to her daughter.

She pulled aside the blind nervously and peered out into the dark grounds.

‘I am sure we’re going to have a visitation tonight,’ she said. ‘I told Mr Goodman so. He said “Stuff and nonsense!”’

‘I wish to heaven you wouldn’t do that, mother,’ snapped the girl. ‘You give me the jumps.’

Mrs Elvery looked in the glass and patted her hair.

‘I’ve seen it twice,’ she said, with a certain uneasy complacency.

Veronica shivered.

For a little while Mrs Elvery said nothing, then, turning dramatically, she lifted her fat forefinger.

‘Cotton!’ she said mysteriously. ‘If that butler’s a butler, I’ve never seen a butler.’

Veronica stared at her aghast.

‘Good lord, Ma, what do you mean?’

‘He’s been snooping around all day. I caught him coming up those stairs from the cellars, and when he saw me he was so taken aback he didn’t know whether he was on his head or his heels.’

‘How do you know he didn’t know?’ asked the practical Veronica, and Mrs Elvery’s testy reply was perhaps justifiable.

Veronica looked at her mother thoughtfully.

‘What did you see, mother—when you squealed the other night?’

‘I wish to goodness you wouldn’t say “squeal”,’ snapped Mrs Elvery. ‘It’s not a word you should use to your mother. I screamed—so would you have. There it was, running about the lawn, waving its hands—ugh!’

‘What was it?’ asked Veronica faintly.

Mrs Elvery turned round in her chair.

‘A monk,’ she said; ‘all black; his face hidden behind a cowl or something. Hark at that!’

It was a night of wind and rain, and the rattle of the lattice had made Mrs Elvery jump.

‘Let’s go downstairs for heaven’s sake,’ she said.

The cheerful Mr Goodman was alone when they reached the lounge, and he gave a little groan at the sight of her and hoped that she had not heard him.

‘Mr Goodman’—he was not prepared for Veronica’s attack—‘did mother tell you what she saw?’

Goodman looked over his glasses with a pained expression.

‘If you’re going to talk about ghosts—’

‘Monks!’ said Veronica, in a hollow voice.

‘One monk,’ corrected Mrs Elvery. ‘I never said I saw more than one.’

Goodman’s eyebrows rose.

‘A monk?’ He began to laugh softly, and, rising from the settee which formed his invariable resting place, he walked across the room and tapped at the panelled wall. ‘If it was a monk, this is the way he should come.’

Mrs Elvery stared at him open-mouthed.

‘Which way?’ she asked.

‘This is the monk’s door,’ explained Mr Goodman with some relish. ‘It is part of the original panelling.’

Mrs Elvery fixed her glasses and looked. She saw now that what she had thought was part of the panelling was indeed a door. The oak was warped and in places worm-eaten.

‘This is the way the old monks came in,’ said Mr Goodman. ‘The legend is that it communicated with an underground chapel which was used in the days of the Reformation. This lounge was the lobby that opened on to the refectory. Of course, it’s all been altered—probably the old passage to the monks’ chapel has been bricked up. The monks used to pass through that chapel every day, two by two—part of their ritual, I suppose, to remind them that life was a very short business.’

Veronica drew a deep breath.

‘On the whole I prefer to talk about mother’s murders,’ she said.

‘A chapel,’ repeated Mrs Elvery intensely. ‘That would explain the organ, wouldn’t it?’

Goodman shook his head.

‘Nothing explains the organ,’ he said. ‘Rich foods, poor digestion.’

And then, to change the subject:

‘You told me that that young man, Fane, was coming here.’

‘He isn’t,’ said Mrs Elvery emphatically. ‘He’s too interesting. They don’t want anybody here but old fogies,’ and, as he smiled, she added hastily: ‘I don’t mean you, Mr Goodman.’

She heard the door open and looked round. It was Mary Redmayne.

‘We were talking about Mr Fane,’ she said.

‘Were you?’ said Mary, a little coldly. ‘It must have been a very dismal conversation.’

All kind of conversation languished after that. The evening seemed an interminable time before the three guests of the house said good-night and went to bed. Her father had not put in an appearance all the evening. He had been sitting behind the locked door of his study. She waited till the last guest had gone and then went and knocked at the door. She heard the cupboard close before the door unlocked.

‘Good-night, my dear,’ he said thickly.

‘I want to talk to you, father.’

He threw out his arms with a weary gesture.

‘I wish you wouldn’t, I’m all nerves tonight.’

She closed the door behind her and came to where he was sitting, resting her hand upon his shoulder.

‘Daddy, can’t we get away from this place? Can’t you sell it?’

He did not look up, but mumbled something about it being dull for her.

‘It isn’t more dull than it was at School,’ she said; ‘but’—she shivered—‘it’s awful! There’s something vile about this place.’

He did not meet her eyes.

‘I don’t understand—’

‘Father, you know that there’s something horrible. No, no, it isn’t my nerves. I heard it last night—first the organ and then that scream!’ She covered her face with her hands. ‘I can’t bear it! I saw him running across the lawn—a terrifying thing in black. Mrs Elvery heard it too—what’s that?’

He saw her start and her face go white. She was listening.

‘Can you hear?’ she whispered.

‘It’s the wind,’ he said hoarsely; ‘nothing but the wind.’

‘Listen!’

Even he must have heard the faint, low tones of an organ as they rose and fell.

‘Can your hear?’

‘I hear nothing,’ he said stolidly.

She bent towards the floor and listened.