Полная версия

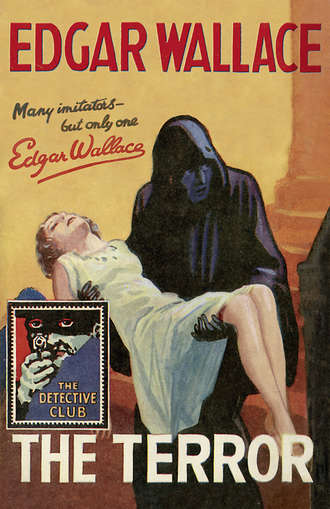

The Terror

GREATEST GOLD ROBBERY OF OUR TIME.

THREE TONS OF GOLD DISAPPEAR BETWEEN SOUTHAMPTON AND LONDON.

DEAD ROBBER FOUND BY THE ROADSIDE.

THE VANISHED LORRY.

In the early hours of yesterday morning a daring outrage was committed which might have led to the death of six members of the C.I.D., and resulted in the loss to the Bank of England of gold valued at half a million pounds.

The Aritania, which arrived in Southampton last night, brought a heavy consignment of gold from Australia, and in order that this should be removed to London with the least possible ostentation, it was arranged that a lorry carrying the treasure should leave Southampton at three o’clock in the morning, arriving in London before the normal flow of traffic started. At a spot near Felsted Wood the road runs down into a depression and through a deep cutting. Evidently this had been laid with gas, and the car dashed into what was practically a lethal chamber without warning.

That an attack was projected, however, was revealed to the guard before they reached the fatal spot. A man sprang out from a hedge and shot at the trolley. The detectives in charge of the convoy immediately replied, and the man was later found in a dying condition. He made no statement except to mention a name which is believed to be that of the leader of the gang.

Sub-Inspectors Bradley and Hallick of Scotland Yard are in charge of the case…

There followed a more detailed account, together with an official statement issued by the police, containing a brief narrative by one of the guards.

‘It seems to have created something of a sensation,’ smiled Marks, as he folded up the paper.

‘What about O’Shea?’ asked the other impatiently. ‘Did he agree to split?’ Marks nodded.

‘He was a little annoyed—naturally. But in his sane moments our friend, O’Shea, is a very intelligent man. What really annoyed him was the fact that we had parked the lorry in another place than where he ordered it to be taken. He was most anxious to discover our little secret, and I think his ignorance of the whereabouts of the gold was our biggest pull with him.’

‘What’s going to happen?’ asked Connor in a troubled tone.

‘We’re taking the lorry tonight to Barnes Common. He doesn’t realise, though he will, that we’ve transferred the gold to a small three-ton van. He ought to be very grateful to me for my foresight, for the real van was discovered this evening by Hallick in the place where O’Shea told me to park it. And of course it was empty.’

Connor rubbed his hand across his unshaven chin.

‘O’Shea won’t let us get away with it,’ he said, with a worried frown. ‘You know him, Soapy.’

‘We shall see,’ said Mr Marks, with a confident smile.

He poured out a whisky and soda.

‘Drink up and we’ll go.’ He glanced at his watch. ‘We’ve got plenty of time—thank God there’s a war on, and the active and intelligent constabulary are looking for spies, the streets are nicely darkened, and all is favourable to our little arrangement. By the way, I’ve had a red cross painted on the tilt of our van—it looks almost official!’

That there was a war on, they discovered soon after they turned into the Embankment. Warning maroons were banging from a dozen stations; the darkened tram which carried them to the south had hardly reached Kennington Oval before the anti-aircraft guns were blazing at the unseen marauders of the skies. A bomb dropped all too close for the comfort of the nervous Connor. The car had stopped.

‘We had better get out here,’ whispered Marks. ‘They won’t move till the raid is over.’

The two men descended to the deserted street and walked southward. The beams of giant searchlights swept the skies; from somewhere up above came the rattle of a machine-gun.

‘This should keep the police thoroughly occupied,’ said Marks, as they turned into a narrow street in a poor neighbourhood. ‘I don’t think we need miss our date, and our little ambulance should pass unchallenged.’

‘I wish to God you’d speak English!’ growled Connor irritably.

Marks had stopped before the gates of a stable yard, pushing them. One yielded to his touch and they walked down the uneven drive to the small building where the car was housed. Soapy put his key into the gate of the lock-up and turned it.

‘Here we are,’ he said, as he stepped inside.

And then a hand gripped him, and he reached for his gun.

‘Don’t make any fuss,’ said the hated voice of Inspector Hallick. ‘I want you, Soapy. Perhaps you’ll tell me what’s happened to this ambulance of yours?’

Soapy Marks stared towards the man he could not see, and for a moment was thrown off his guard.

‘The lorry?’ he gasped. ‘Isn’t it here?’

‘Been gone an hour,’ said a second voice. ‘Come across, Soapy; what have you done with it?’

Soapy said nothing; he heard the steel handcuffs click on the wrist of Joe Connor, heard that man’s babble of incoherent rage and blasphemy as he was hustled towards the car which had drawn up silently at the gate, and knew that Mr O’Shea was indeed very sane on that particular day.

CHAPTER III

TO Mary Redmayne life had been a series of inequalities. She could remember the alternate prosperity and depression of her father; had lived in beautiful hotel suites and cheap lodgings, one following the other with extraordinary rapidity; and had grown so accustomed to the violent changes of his fortune that she would never have been surprised to have been taken from the pretentious school where she was educated, and planted amongst county school scholars at any moment.

People who knew him called him Colonel, but he himself preferred his civilian title, and volunteered no information to her as to his military career. It was after he had taken Monkshall that he permitted ‘Colonel’ to appear on his cards. It was a grand-sounding name, but even as a child Mary Redmayne had accepted such appellations with the greatest caution. She had once been brought back from her preparatory school to a ‘Mortimer Lodge’, to discover it was a tiny semi-detached villa in a Wimbledon by-street.

But Monkshall had fulfilled all her dreams of magnificence; a veritable relic of Tudor times, and possibly of an earlier period, it stood in forty acres of timbered ground, a dignified and venerable pile, which had such association with antiquity that, until Colonel Redmayne forbade the practice, charabancs full of American visitors used to come up the broad drive and gaze upon the ruins of what had been a veritable abbey.

Fortune had come to Colonel Redmayne when she was about eleven. It came unexpectedly, almost violently. Whence it came, she could not even guess; she only knew that one week he was poor, harassed by debt-collectors, moving through side streets in order to avoid his creditors; the next week—or was it month?—he was master of Monkshall, ordering furniture worth thousands of pounds.

When she went to live at Monkshall she had reached that gracious period of interregnum between child and woman. A slim girl above middle height, straight of back, free of limb, she held the eye of men to whom more mature charms would have had no appeal.

Ferdie Fane, the young man who came to the Red Lion so often, summer and winter, and who drank so much more than was good for him, watched her passing along the road with her father. She was hatless; the golden-brown hair had a glory of its own; the faultless face, the proud little lift of her chin.

‘Spring is here, Adolphus,’ he addressed the landlord gravely. ‘I have seen it pass.’

He was a man of thirty-five, long-faced, rather good-looking in spite of his huge horn-rimmed spectacles. He had a large tankard of beer in his hand now, which was unusual, for he did most of his drinking secretly in his room. He used to come down to the Red Lion at all sorts of odd and sometimes inconvenient moments. He was, in a way, rather a bore, and the apparition of Mary Redmayne and her grim-looking father offered the landlord an opportunity for which he had been seeking.

‘I wonder you don’t go and stay at Monkshall, Mr Fane,’ he suggested.

Mr Fane stared at him reproachfully.

‘Are you tired of me, mine host?’ he asked gently. ‘That you should shuffle me into other hands?’ He shook his head. ‘I am no paying guest—besides which, I am not respectable. Why does Redmayne take paying guests at all?’

The landlord could offer no satisfactory solution to this mystery.

‘I’m blessed if I know. The colonel’s got plenty of money. I think it is because he’s lonely, but he’s had paying guests at Monkshall this past ten years. Of course, it’s very select.’

‘Exactly,’ said Ferdie Fane with great gravity. ‘And that is why I should not be selected! No, I fear you will have to endure my erratic visits.’

‘I don’t mind your being here, sir,’ said the landlord, anxious to assure him. ‘You never give me any trouble, only—’

‘Only you’d like somebody more regular in his habits—good luck!’

He lifted the foaming pewter to his lips, took a long drink, and then he began to laugh softly, as though at some joke. In another minute he was serious again, frowning down into the tankard.

‘Pretty girl, that. Mary Redmayne, eh?’

‘She’s only been back from school a month—or college, rather,’ said the landlord. ‘She’s the nicest young lady that ever drew the breath of life.’

‘They all are,’ said the other vaguely. He went away the next day with his fishing rod that he hadn’t used, and his golf bag which had remained unstrapped throughout his stay.

Life at Monkshall promised so well that Mary Redmayne was prepared to love the place. She liked Mr Goodman, the grey-haired, slow-spoken gentleman who was the first of her father’s boarders; she loved the grounds, the quaint old house; could even contemplate, without any great uneasiness, the growing taciturnity of her father. He was older, much older than he had been; his face had a new pallor; he seldom smiled. He was a nervous man, too; she had found him walking about in the middle of the night, and once had surprised him in his room, suspiciously thick of speech, with an empty whisky bottle a silent witness to his peculiar weakness.

It was the house that began to get on her nerves. Sometimes she would wake up in the middle of the night suddenly and sit up in bed, trying to recall the horror that had snatched her from sleep and brought her through a dread cloud of fear to wakefulness. Once she had heard peculiar sounds that had sent cold shivers down her spine. Not once, but many times, she thought she heard the faint sound of a distant organ.

She asked Cotton, the dour butler, but he had heard nothing. Other servants had been more sensitive, however; there came a constant procession of cooks and housemaids giving notice. She interviewed one or two of these, but afterwards her father forbade her seeing them, and himself accepted their hasty resignations.

‘This place gives me the creeps, miss,’ a weeping housemaid had told her. ‘Do you hear them screams at night? I do; I sleep in the east wing. The place is haunted—’

‘Nonsense, Anna!’ scoffed the girl, concealing a shudder. ‘How can you believe such things!’

‘It is, miss,’ persisted the girl. ‘I’ve seen a ghost on the lawn, walking about in the moonlight.’

Later, Mary herself began to see things; and a guest who came and stayed two nights had departed a nervous wreck.

‘Imagination,’ said the colonel testily. ‘My dear Mary, you’re getting the mentality of a housemaid!’

He was very apologetic afterwards for his rudeness, but Mary continued to hear, and presently to listen; and finally she saw…Sights that made her doubt her own wisdom, her own intelligence, her own sanity.

One day, when she was walking alone through the village, she saw a man in a golf suit; he was very tall and wore horn-rimmed spectacles, and greeted her with a friendly smile. It was the first time she had seen Ferdie Fane. She was to see very much of him in the strenuous months that followed.

CHAPTER IV

SUPERINTENDENT HALLICK went down to Princetown in Devonshire to make his final appeal—an appeal which, he knew, was foredoomed to failure. The Deputy-Governor met him as the iron gates closed upon the burly superintendent.

‘I don’t think you’re going to get very much out of these fellows, superintendent,’ he said. ‘I think they’re too near to the end of their sentence.’

‘You never know,’ said Hallick, with a smile. ‘I once had the best information in the world from a prisoner on the day he was released.’

He went down to the low-roofed building which constitutes the Deputy-Governor’s office.

‘My head warder says they’ll never talk, and he has a knack of getting into their confidence,’ said the Deputy. ‘If you remember, superintendent, you did your best to make them speak ten years ago, when they first came here. There’s a lot of people in this prison who’d like to know where the gold is hidden. Personally, I don’t think they had it at all, and the story they told at the trial, that O’Shea had got away with it, is probably true.’

The superintendent pursed his lips.

‘I wonder,’ he said thoughtfully. ‘That was the impression I had the night I arrested them, but I’ve changed my opinion since.’

The chief warder came in at that moment and gave a friendly nod to the superintendent.

‘I’ve kept those two men in their cells this morning. You want to see them both, don’t you, superintendent?’

‘I’d like to see Connor first.’

‘Now?’ asked the warder. ‘I’ll bring him down.’

He went out, passed across the asphalt yard to the entrance of the big, ugly building. A steel grille covered the door, and this he unlocked, opening the wooden door behind, and passed into the hall, lined on each side with galleries from which opened narrow cell doors. He went to one of these on the lower tier, snapped back the lock and pulled open the door. The man in convict garb who was sitting on the edge of the bed, his face in his hands, rose and eyed him sullenly.

‘Connor, a gentleman from Scotland Yard has come down to see you. If you’re sensible you’ll give him the information he asks.’

Connor glowered at him.

‘I’ve nothing to tell, sir,’ he said sullenly. ‘Why don’t they leave me alone? If I knew where the stuff was I wouldn’t tell ’em.’

‘Don’t be a fool,’ said the chief good-humouredly. ‘What have you to gain by hiding up—?’

‘A fool, sir?’ interrupted Connor. ‘I’ve had all the fool knocked out of me here!’ His hand swept round the cell. ‘I’ve been in this same cell for seven years; I know every brick of it—who is it wants to see me?’

‘Superintendent Hallick.’

Connor made a wry face.

‘Is he seeing Marks too? Hallick, eh? I thought he was dead.’

‘He’s alive enough.’

The chief beckoned him out into the hall, and, accompanied by a warder, Connor was taken to the Deputy’s office. He recognised Hallick with a nod. He bore no malice; between these two men, thief-taker and thief, was that curious camaraderie which exists between the police and the criminal classes.

‘You’re wasting your time with me, Mr Hallick,’ said Connor. And then, with a sudden burst of anger: ‘I’ve got nothing to give you. Find O’Shea—he’ll tell you! And find him before I do, if you want him to talk.’

‘We want to find him, Connor,’ said Hallick soothingly.

‘You want the money,’ sneered Connor; ‘that’s what you want. You want to find the money for the bank and pull in the reward.’ He laughed harshly. ‘Try Soapy Marks—maybe he’ll sit in your game and take his corner.’

The lock turned at that moment and another convict was ushered into the room. Soapy Marks had not changed in his ten years of incarceration. The gaunt, ascetic face had perhaps grown a little harder; the thin lips were firmer, and the deep-set eyes had sunk a little more into his head. But his cultured voice, his exaggerated politeness, and that oiliness which had earned him his nickname, remained constant.

‘Why, it’s Mr Hallick!’ His voice was a gentle drawl. ‘Come down to see us at our country house!’

He saw Connor and nodded, almost bowed to him.

‘Well, this is most kind of you, Mr Hallick. You haven’t seen the park or the garage? Nor our beautiful billiard-room?’

‘That’ll do, Marks,’ said the warder sternly.

‘I beg your pardon, sir, I’m sure.’ The bow to the warder was a little deeper, a little more sarcastic. ‘Just badinage—nothing wrong intended. Fancy meeting you on the moor, Mr Hallick! I suppose this is only a brief visit? You’re not staying with us, are you?’

Hallick accepted the insult with a little smile.

‘I’m sorry,’ said Marks. ‘Even the police make little errors of judgment sometimes. It’s deplorable, but it’s true. We once had an ex-inspector in the hall where I am living.’

‘You know why I’ve come?’ said Hallick.

Marks shook his head, and then a look of simulated surprise and consternation came to his face.

‘You haven’t come to ask me and my poor friend about that horrible gold robbery? I see you have. Dear me, how very unfortunate! You want to know where the money was hidden? I wish I could tell you. I wish my poor friend could tell you, or even your old friend, Mr Leonard O’Shea.’ He smiled blandly. ‘But I can’t!’

Connor was chafing under the strain of the interview.

‘You don’t want me any more—’

Marks waved his hand.

‘Be patient with dear Mr Hallick.’

‘Now look here, Soapy,’ said Connor angrily, and a look of pain came to Marks’ face.

‘Not Soapy—that’s vulgar. Don’t you agree, Mr Hallick?’

‘I’m going to answer no questions. You can do as you like,’ said Connor. ‘If you haven’t found O’Shea, I will, and the day I get my hands on him he’ll know all about it! There’s another thing you’ve got to know, Hallick; I’m on my own from the day I get out of this hell. I’m not asking Soapy to help me to find O’Shea. I’ve seen Marks every day for ten years, and I hate the sight of him. I’m working single-handed to find the man who shopped me.’

‘You think you’ll find him, do you?’ said Hallick quickly. ‘Do you know where he is?’

‘I only know one thing,’ said Connor huskily, ‘and Soapy knows it too. He let it out that morning we were waiting for the gold lorry. It just slipped out—what O’Shea’s idea was of a quiet hiding-place. But I’m not going to tell you. I’ve got four months to serve, and when that time is up I’ll find O’Shea.’

‘You poor fool!’ said Hallick roughly. ‘The police have been looking for him for ten years.’

‘Looking for what?’ demanded Connor, ignoring Marks’ warning look.

‘For Len O’Shea,’ said Hallick.

There came a burst of laughter from the convict.

‘You’re looking for a sane man, and that’s where you went wrong! I didn’t tell you before why you’ll never find him. It’s because he’s mad! You didn’t know that, but Soapy knows. O’Shea was crazy ten years ago. God knows what he is now! Got the cunning of a madman. Ask Soapy.’

It was news to Hallick. His eyes questioned Marks, and the little man smiled.

‘I’m afraid our dear friend is right,’ said Marks suavely. ‘A cunning madman! Even in Dartmoor we get news, Mr Hallick, and a rumour has reached me that some years ago three officers of Scotland Yard disappeared in the space of a few minutes—just vanished as though they had evaporated like dew before the morning sun! Forgive me if I am poetical; Dartmoor makes you that way. And would you be betraying an official secret if you told me these men were looking for O’Shea?’

He saw Hallick’s face change, and chuckled.

‘I see they were. The story was that they had left England and they sent their resignations—from Paris, wasn’t it? O’Shea could copy anybody’s handwriting—they never left England.’ Hallick’s face was white.

‘By God, if I thought that—’ he began.

‘They never left England,’ said Marks remorselessly. ‘They were looking for O’Shea—and O’Shea found them first.’

‘You mean they’re dead?’ asked the other.

Marks nodded slowly.

‘For twenty-two hours a day he is a sane, reasonable man. For two hours—’ He shrugged his shoulders. ‘Mr Hallick, your men must have met him in one of his bad moments.’

‘When I meet him—’ interrupted Connor, and Marks turned on him in a flash.

‘When you meet him you will die!’ he hissed. ‘When I meet him—’ That mild face of his became suddenly contorted, and Hallick looked into the eyes of a demon.

‘When you meet him?’ challenged Hallick. ‘Where will you meet him?’

Marks’ arm shot out stiffly; his long fingers gripped an invisible enemy.

‘I know just where I can put my hand on him,’ he breathed. ‘That hand!’

Hallick went back to London that afternoon, a baffled man. He had gone to make his last effort to secure information about the missing gold, and had learned nothing—except that O’Shea was sane for twenty-two hours in the day.

CHAPTER V

IT was a beautiful spring morning. There was a tang in the air which melted in the yellow sunlight.

Mr Goodman had not gone to the city that morning, though it was his day, for he made a practice of attending at his office for two or three days every month. Mrs Elvery, that garrulous woman, was engaged in putting the final touches to her complexion; and Veronica, her gawkish daughter, was struggling, by the aid of a dictionary, with a recalcitrant poem—for she wooed the gentler muse in her own gentler moments.

Mr Goodman sat on a sofa, dozing over his newspaper. No sound broke the silence but the scratching of Veronica’s pen and the ticking of the big grandfather’s clock.

This vaulted chamber, which was the lounge of Monkshall, had changed very little since the days when it was the anteroom to a veritable refectory. The columns that monkish hands had chiselled had crumbled a little, but their chiselled piety, hidden now behind the oak panelling, was almost as legible as on the day the holy men had written them.

Through the open French window there was a view of the broad, green park, with its clumps of trees and its little heap of ruins that had once been the Mecca of the antiquarian.

Mr Goodman did not hear the excited chattering of the birds, but Miss Veronica, in that irritable frame of mind which a young poet can so readily reach, turned her head once or twice in mute protest.

‘Mr Goodman,’ she said softly.

There was no answer, and she repeated his name impatiently.

‘Mr Goodman!’

‘Eh?’ He looked up, startled.

‘What rhymes with “supercilious”?’ asked Veronica sweetly.

Mr Goodman considered, stroking chin reflectively.

‘Bilious?’ he suggested.

Miss Elvery gave a despairing cluck.

‘That won’t do at all. It’s such an ugly word.’

‘And such an ugly feeling,’ shuddered Mr Goodman. Then: ‘What are you writing?’ he asked.

She confessed to her task.

‘Good heavens!’ he said despairingly. ‘Fancy writing poetry at this time in the morning! It’s almost like drinking before lunch. Who is it about?’

She favoured him with an arch smile. ‘You’ll think I’m an awful cat if I tell you.’ And, as he reached out to take her manuscript: ‘Oh, I really couldn’t—it’s about somebody you know.’

Mr Goodman frowned.

‘“Supercilious” was the word you used. Who on earth is supercilious?’

Veronica sniffed—she always sniffed when she was being unpleasant.

‘Don’t you think she is—a little bit? After all, her father only keeps a boarding house.’

‘Oh, you mean Miss Redmayne?’ asked Goodman quietly. He put down his paper. ‘A very nice girl. A boarding house, eh? Well, I was the first boarder her father ever had, and I’ve never regarded this place as a boarding house.’

There was a silence, which the girl broke. ‘Mr Goodman, do you mind if I say something?’