Полная версия

Sea-Birds

The Tristan great shearwater nests only on Nightingale and Inaccessible Islands, in the Tristan da Cunha group; possibly a few may survive on Tristan itself. The population remains vast, though ‘farmed’ by the Tristan islanders, and an annual penetration of the North Atlantic by off-season birds has put the species on the list of regular and expected visitors to both West Atlantic and East Atlantic waters, as well as some arctic waters of Greenland. The northward movement reaches the North Atlantic in May, mostly on the west side at first, but odd birds appear in Irish and west British waters in June and have even been seen then in the Skagerak; one of us saw a few already at Rockall in mid-May (1949), and they were abundant there and in moult by late June (1948).

The Tristan great shearwater seldom comes close to land, and it is never common in British waters within sight of shore; but some distance to sea off west England, Ireland and the Hebrides it is always present in July and August; and some elements usually penetrate northabout into the North Sea, descending to the latitude of Yorkshire. The Tristan great shearwater is much more common than the Northern Atlantic shearwater in our seas; indeed, the Mediterranean race of the latter P. d. diomedea, and Cory’s race P. d. borealis, have each only once been taken ashore in Britain, although birds which may have been of Cory’s subspecies have several times been seen at the entrance of the Channel. The only Scottish record is of one, seen at sea close to Aberdeen on 10 September 1947, by R. N. Winnall. Normally as Wynne-Edwards and Rankin and Duffey have shown, Puffinus diomedea does not get much farther north in the Atlantic than 50°N., and that at about 30°W. It is much more common on the North American coast than on that of Britain, although this coast is much farther from its base; ‘they seem to arrive on our coasts early in August,’ writes Bent, ‘and spend the next three months with us, mainly between Cape Cod and Long Island Sound.’ The Tristan great shearwater also probably reaches its greatest abundance on the North American coast, particularly in the area of the Newfoundland Banks, where it is known as the ‘hagdon’; from here it extends every season along the coast of Labrador to Greenland;—it has been recorded near Iceland.

The other southern hemisphere shearwater that regularly visits North Atlantic waters is Puffinus griseus, the sooty shearwater. It is much rarer than the Tristan great shearwater, though it has been seen in British waters regularly enough to be classed as an autumn visitor. It breeds in New Zealand and its islands, in southern South America and its islands, and the Falkland Islands (in places many miles inland), and ranges the Pacific as well as the Atlantic; its Atlantic population is low compared with that of the other southern shearwater. Unlike the Tristan great shearwater, it probably makes its way into the North Sea by the Channel; and it is regular in small numbers in the Western approaches. At Rockall on 17 May 1949 J.F. saw none, but from 18 to 27 June 1948 R.M.L. found them always present there, singly and up to eight together, that is in the proportion of about one to a hundred hagdons. On the Newfoundland Banks, where it is in the same proportion, the fishermen called it the haglet. It reaches Greenland and Icelandic waters, and has been seen once as far north as Bear Island.

The storm-petrel from the south is Wilson’s petrel Oceanites oceanicus, which nests in vast numbers in the antarctic continent and on the southern islands of South Shetland, South Orkney, South Georgia, Falkland, Tierra del Fuego and Kerguelen. It disperses into, and across, the Equator in the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific Oceans. Wilson’s petrel has been the subject of an exhaustive monograph by Brian Roberts (1940), who mapped the dispersal in the Atlantic month by month (Fig. 29). Records north of the Equator are only irregular and sporadic between November and March, but in April the species is spread widely over the western half of the North Atlantic as far as Cape Cod. In May the petrels spread eastwards reaching from Cape Cod across the Atlantic towards Portugal and the Bay of Biscay, off which there is quite a concentration in June. By July there is a band of Wilson’s petrels across the whole North Atlantic with its northern border at about 40°N., but not reaching Britain. In August the eastern Atlantic petrels disappear, though on the west a concentration remains with its nucleus near Long Island Sound; and this persists in reduced population in September, by which time most Wilson’s petrels are making their way home. In September they reappear again off Portugal, and the homeward stream in October runs south along the north-west coast of Africa, continues its line across the Atlantic to the corner of Brazil, and carries on mainly down the east coast of South America; in November and December the concentration is at its greatest in the triangle Rio de Janeiro-South Georgia-Cape Horn.

There are only about ten records for this abundant and successful species, in Britain. It does not normally reach our islands, though elements cannot be within much more than a few hundred miles of Cornwall in June and July. Most of the British records are between October and December—suggesting young non-breeding birds, inexperienced in the ways of wind and wave.

Among the two dozen casual sea-bird visitors to the North Atlantic undoubtedly the most exciting are the kings of the tubenoses—the albatrosses, whose occurences in the North-Atlantic-Arctic are really monuments not so much to the fact that from time to time the best-adapted birds make mistakes and get right out of their range, as to the extraordinary powers of endurance and flight of the world’s greatest oceanic birds. Five albatrosses have strayed into the North Atlantic, four of the genus Diomedea, which includes the largest kinds, and one Phoebetria. All breed in the southern regions of the southern hemisphere.

The most frequent in occurrence has been the black-browed albatross D. melanophris, of which we can trace nine records. The first of these is astonishing; on 15 June 1878, north-west of Spitsbergen and north of latitude 80°N., the whaler-skipper David Gray shot one that is now in the Peterhead Museum; it was farther north than the species ever gets south, even though it nests to latitude 55°S. Another northerly record is from West Greenland, and others have been shot south-west of the Faeroes and in the Oslo Fjord, Norway; one is even alleged to have reached Oesel in the Baltic. In 1860 (Andersen 1894) a female black-browed albatross turned up among the gannets of Mýkinesholmur in Faeroe, and came to the cliff every season with them until 11 May 1894, when it was shot by P. F. Petersen. For many years the only British record was of one which was caught exhausted in a field near Linton, Cambridgeshire, on 9 July 1897; but on 14 May 1949 an immature albatross which was probably of this species was seen at the Fair Isle, between Orkney and Shetland. It was first noticed soaring off the south face of the Sheep Craig, the famous landmark on the east side of the island, and obligingly glided over George Waterston, G. Hughes-Onslow and W. P. Vicary, who got a fine view of it (Williamson 1950, 1950b). Further, in September 1952 one was picked up alive in Derbyshire (Edmunds, 1952; Serventy, Clancey and Elliott, 1953).

No other albatross has been certainly seen in Britain: a record of the yellow-nosed albatross from the Lincolnshire-Nottinghamshire boundary on 25 November 1836 is not admitted to the British list. This species, D. chlororhynchos, has been certainly obtained, however, in south Iceland, at the mouth of the St. Lawrence river, in the Bay of Fundy (New Brunswick), and in Oxford County, Maine. A record of D. chrysostoma from Bayonne in France* may possibly refer to this species, for D. chlororhynchos and D. chrysostoma are extremely similar, and almost impossible to distinguish in the field. D. chrysostoma, the grey-headed albatross, has, however, certainly been recorded once in the North Atlantic—from South Norway in 1837 (or 1834). The light-mantled sooty albatross Phoebetria palpebrata, a relatively small species which breeds on sub-antarctic islands, has been recorded from Dunkirk, France*. The greatest of all the albatrosses, the wandering albatross Diomedea exulans, has been taken, in France (Dieppe), Belgium (Antwerp) and on the Atlantic coast of Morocco; this magnificent animal has a wingspread up to 111⁄2 feet and may weigh seventeen pounds or more; we can imagine the excitement of those humans who encountered these South Atlantic wanderers on their North Atlantic wanderings!

Sometimes these wanderings may end in queer places; for instance, F. J. Stubbs (1913) found an albatross that he judged to be D. exulans hanging among the turkeys of Christmas 1909 in a game-dealer’s shop in Leadenhall Market. When he saw it ‘the bird appeared quite fresh, and bright red blood was dripping from its beak.’ There was no indication whence it had been obtained.

Unidentified albatrosses have been seen at sea west of Spitsbergen on 2 May 1885, by the Captain David Gray who shot the 1878 black-browed albatross; off the mouth of Loch Linnhe, West Highlands of Scotland, in the autumn of 1884 by W. Rothschild; and twenty miles north-west of Orkney on 18 July 1894, by J. A. Harvie-Brown (1895).

Apart from the three regular non-breeding summer visitors and the albatrosses, at least six other tubenoses have wandered into the North Atlantic from the South, or from the Pacific. The Cape pigeon Daption capensis, has been recorded from France*, Holland and Maine, but the three British records have been rejected from the official list on the grounds that sailors have been known to liberate captured specimens in the Channel. Quite probably they are valid. Peale’s or the scaled petrel Pterodroma inexpectata, has once been taken in New York State. Pterodroma neglecta, the Kermadec petrel, has been once found dead in Britain (on 1 April 1908 near Tarporley in Cheshire). One Trinidad petrel Pterodroma arminjoniana, was driven to New York by the hurricane of August 1933, and possibly this close Atlantic relative of the Kermadec petrel may cross the equator fairly often, as it breeds on South Trinidad Island (only), which is fourteen hundred miles south of the equator, surely no very great distance for a petrel. One collared petrel Pterodroma leucoptera, a Pacific species, was shot between Borth and Aberystwyth in Cardiganshire, Wales, at the end of November or the beginning of December 1889. The last wandering tubenose is the black-bellied storm-petrel Fregetta tropica, a sub-antarctic species which was first collected off the coast of Sierra Leone and has also been taken in Florida. It seems likely that this last species may cross the equator fairly regularly, at least as far as the Tropic of Cancer.

One Pelecaniform wanderer has crossed the equator into the North Atlantic from South Africa—the Cape gannet Sula capensis, which may reach north to the Canaries.

From the western United States the California gull Larus californicus (which may be a race of the herring-gull, see here) winters fairly regularly to Texas, and thus (in our definition) to the North Atlantic region. Another gull which enters the North Atlantic, from more distant breeding-grounds, is the great black-headed gull, Larus ichthyaëtus of the Black Sea and farther east, which has reached Madeira and Belgium and has been seen in Britain about eight times.

Four exotic terns have wandered into the North Atlantic. The South American Trudeau’s tern Sterna trudeaui, has once reached New Jersey. On the east side Sterna balaenarum, the Damara tern of South Africa, has migrated across the equator as far as Lagos in Nigeria. Thalasseus bergii, the swift tern, breeds on the west coast of South Africa north to Walvis Bay, whence occasional individuals may sometimes pass north across the equator. The elegant tern Thalasseus elegans, of the Gulf of California, has accidentally reached Texas. And finally Gygis alba, the tropical, white, almost ‘transparent’ fairy tern breeds north in the Atlantic to Fernando Noronha, and therefore probably occasionally operates across the two hundred miles that would bring it to the North Atlantic, though there is so far no formal record of this. It has a wide distribution in all tropical seas, but is very much attached to, and does not often fly far from, its breeding-grounds; nevertheless R. C. Murphy (1936) ponders: ‘Since there are seasons when powerful southeast trade winds blow from Fernando Noronha across the equator almost as far as the mouth of the River Orinoco, speculation offers me no clue as to why Gygis has not succeeded in jumping the next gap and establishing itself in the West Indies.’

The remaining wanderers are from the North Pacific—auks from that cradle of the sub-order of auks. Aethia pusilla, the least auklet, has not actually reached the Atlantic, but one was found ‘halfway’ from the Pacific to the Atlantic, in the Mackenzie delta in May 1927. The ancient murrelet Synthliboramphus antiquus has been found three times in the Great Lakes area, but no farther east. Aethia psittacula, the paroquet auklet,* has actually reached the Atlantic by turning up in, of all places, Sweden: in December 1860 one was captured in Lake Vattern! If the least auklet has not reached the Atlantic, its congener Aethia cristatella, the crested auklet, has, for even if we reject (as most do) the alleged Massachusetts record, we must accept that of 15 August 1912 when one was shot north-east of Iceland. Finally Lunda cirrhata, the tufted puffin, was obtained by the great naturalist Audubon in Maine: other records from the Bay of Fundy and Greenland are erroneous.

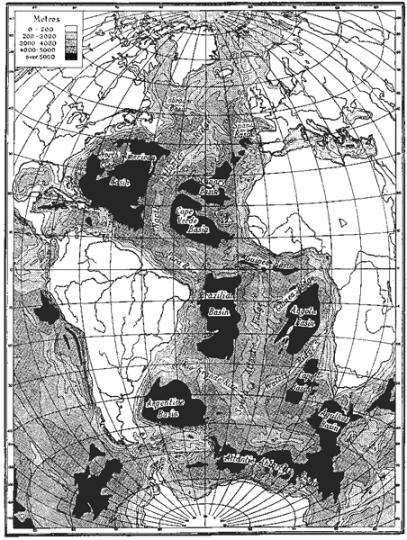

FIG. 2c Bathymetrical sketch-chart of the Atlantic Ocean

CHAPTER 2 EVOLUTION AND THE NORTH ATLANTIC SEA-BIRDS

GEOLOGISTS DIFFER in their opinions of the origin of the Atlantic Ocean. The followers of the geomorphologist Alfred Wegener believe that it is a real crack in the earth’s crust whose lips have drifted away from each other, and this opinion is lent verisimilitude by the neat way in which the east coast of the Americas can be applied to, and will fit with extraordinary exactitude, the west coast of Europe and Africa. It must be stated that, while the present opinion of most geographers is that the resemblance of the Atlantic to a drifted crack is purely coincidental, this is not shared by all students of animal distribution and evolution, some of whom, find the Wegener theory the most economical hypothesis to account for the present situation.

Whatever the truth is, there is no doubt that the boundaries of the Atlantic, and their interconnections, have varied considerably; thus halfway through the Cretaceous Period, about ninety million years ago (during this long period nearly all the principal orders of birds evolved), there were bridges between Europe, Greenland and Eastern North America cutting the Arctic Ocean from the North Atlantic completely; and from then until the late Pliocene—perhaps only two million years ago—there was no continuous Central American land bridge, but a series of islands.

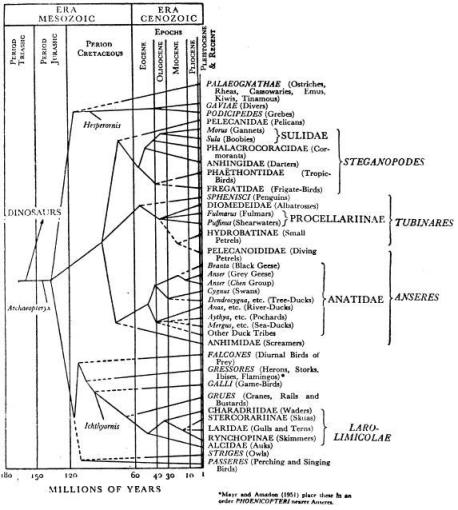

Our present knowledge of the tree of bird evolution owes much to Alexander Wetmore and his school, who have so notably added to our knowledge of fossil birds during the last twenty years, especially in North America. Birds do not appear very frequently in the sedimentary rocks—their fossil population does not generally reflect their true population in the same way as that of mammals is reflected. However, if land-birds are rare in the beds, water-birds are relatively common, and the periods and epochs in which all our sea-bird orders, and many of our sea-bird families and genera, originated are quite well known. A recent paper by Hildegarde Howard (1950), of the school of Wetmore, enables us to show a diagrammatic family tree of birds (Fig. 3), with special reference to sea-birds, and to collate its branching with the approximate time scale of the epochs, so cleverly established by geomorphologists in recent years from studies of sedimentation-rate and the radioactivity of rocks. It will be seen that the primary radiation of birds and the great advances into very different habitats consequent upon the first success of the new animal invention—feathered flight—took place in the Cretaceous period, the first birdlike feathered animals having been found as fossils in Jurassic deposits of the previous period, over a hundred and twenty million years old. In the Cretaceous period—the period of reptiles—ostriches were already foreshadowed, as were grebes and divers, and the pelican-like birds, and the ducks.

In the Cenozoic period—the period of mammals—the radiation of birds into all nature’s possible niches continued rapidly, especially in the first two of its epochs—Eocene and Oligocene—from sixty to thirty million years ago. In these epochs grebes can be distinguished from divers, and a bird of the same apparent genus (Podiceps, or, as the North Americans have it, Colymbus) as modern grebes has been found. Gannet-boobies of the modern genus Sula have been found in the Oligocene, as have cormorants of the modern genus Phalacrocorax. The only penguin fossils known are later—of Miocene age—but it seems probable that they share a common stem with the tubenoses, which would mean that their ancestors branched off in the Eocene. The tubenoses diversified in the Oligocene—from this epoch we have a shearwater of the modern genus Puffinus; and from the Miocene Fulmarus and albatrosses. The ducks started their main evolution in the Cretaceous, and by the Oligocene we find modern genera such as Anas (mallard-like) and Aythya (pochard-like); in the Pliocene we have Bucephala (Charitonetta)—one of the tribe of sea-ducks.

For the Lari-Limicolae, the order which includes waders, gulls and auks, the fossil record is rather indefinite, mainly owing to the difficulty of distinguishing the present families by bones alone. However, we know that the auk family was early—an Eocene offshoot; that the waders and gulls diverged in the Oligocene; and that the gulls, terns and skuas probably diverged in the Miocene—which means that an important part of the adaptive radiation of this order was comparatively late. One of the early auks, the Pliocene Mancalla of California, out-penguined the great auk, Alca (Pinguinus) impennis, for it had progressed far beyond it in the development of a swimming wing.

FIG. 3

Diagrammatic family tree of sea-birds, mainly after Hildegarde Howard (1950)

According to Howard (1950) a few living species of birds have been recorded from the Upper Pliocene, but large numbers of modern forms occurred in the Pleistocene. Of course in the Pleistocene the oceans approximated very closely to what they are today, with the Central American land-bridge closed, the Norwegian Sea wide open between Arctic and Atlantic Oceans, the Mediterranean a blind diverticulum of the North Atlantic. We need this picture as a background to a consideration of the North Atlantic’s present sea-bird fauna, for we shall find that it has few sea-bird species of its own, and only two genera; for the primary sea-bird species which now breed in the Atlantic (and Mediterranean) and in the neighbouring parts of the Arctic, and nowhere else in the world, are no more than twelve: the Manx shearwater Puffinus puffinus*; the very rare diablotin and cahow of the West Indies and Bermuda (Pterodroma hasitata and P. cahow); the storm-petrel Hydrobates pelagicus; the North Atlantic gannet Sula bassana; the shag Phalacrocorax aristotelis; the lesser black-back Larus fuscus; the great blackback L. marinus; the Mediterranean gulls L. melanocephalus and L. audouinii; the Sandwich tern Thalasseus sandvicensis; the razorbill Alca torda, the puffin Fratercula arctica; besides the extinct Alca impennis, the great auk. The two present genera peculiar to the North-Atlantic-Arctic are Hydrobates and Alca.

The sea-birds which qualify by birth and residence to be members of the North Atlantic fauna (excluding purely Arctic and Mediterranean species) include thirteen tubenoses, seventeen cormorant-pelicans, fourteen gulls, nineteen terns, two skimmers, four skuas and five auks (besides various secondary sea-birds, notably about eighteen ducks, three divers and two phalaropes). If we are to understand how these have got into the North Atlantic we should analyse the present distribution of the sea-bird orders and groups as between the different oceans.

The most primitive group of sea-birds, yet the most specialized, is that of the penguins. The Sphenisci have fifteen species in all, of which eight breed in the South Pacific, seven in the Antarctic Ocean, five in the South Atlantic and two in the Indian Ocean. One (and one only) reaches the Equator, and thus the North Pacific, at the Galapagos Islands. No live wild penguin has ever been seen in the North Atlantic.* It seems certain that the evolution of this order of birds has taken place in Antarctica and in the neighbouring sectors of the South Pacific.

The great order of Tubinares the albatrosses, petrels and shearwaters, probably originated in what is now the South Pacific. Nobody knows exactly how many species belong to this order, as there is a good deal of disorder in the published systematics of this very difficult group; but the number is certainly eighty-six, and may be over ninety. Of these fifty-four breed in the South Pacific, twenty-seven in the Antarctic, twenty-five in the North Pacific, twenty-four in the South Atlantic, seventeen in the Indian Ocean, thirteen in the North Atlantic, three in the Mediterranean, and only one, the fulmar, in the Arctic Ocean.

The Steganopodes are an order which is particularly well represented in the South Pacific and Indian Oceans. The pelicans, gannets, cormorants, darter, tropic– and frigate-birds number fifty-four species in all. Thirty-one breed in the South Pacific. Twenty-eight breed in the Indian Ocean. The North Pacific has twenty-three, the South Atlantic twenty, the North Atlantic sixteen, the Mediterranean six, the Antarctic three, and the Arctic two. The present distribution suggests that the order radiated from what is now the East Indian region—from south-east Asia or Australasia.

In the order Laro-Limicolae the family Chionididae, two curious pigeon-like sheathbills, Chionis, are found in Antarctica; and one also breeds in the South Atlantic and South Pacific.

In the family Laridae the gulls (subfamily Larinae) number forty-two. In the North Pacific sixteen of these breed, in the North Atlantic fourteen, in the Arctic eleven, in the South Pacific nine, in the Indian Ocean six, in the South Atlantic five, in the Mediterranean five, in the Antarctic two. Besides these two breed inland only in North America, one inland only in South America, and three inland only in the Palearctic Region. This appears to be the only group of sea-birds whose evolutionary radiation may have taken place from the north; the Arctic and neighbouring parts of the North Pacific and Atlantic appears to be the origin of the gulls. The terns (subfamily Sterninae) number thirty-nine, of which twenty-three breed in the North and twenty-two in the South Pacific, nineteen in the Indian Ocean, nineteen in the North Atlantic, fifteen in the South Atlantic, ten in the Mediterranean, two in the Antarctic, two in the Arctic and one inland only in South America. The radiation of terns appears to be pretty general over the world’s seas, and they may have originated in the tropics, perhaps in the Indian Region. The skuas (subfamily Stercorariinae) have only four species, one of which (Catharacta skua, the great skua) has its breeding-headquarters in the Antarctic; it also breeds in the South Pacific, South and North Atlantic. The other skuas have an arctic breeding-distribution which extends into the North Pacific and North Atlantic. The three skimmers Rynchops belong to a separate family, Rynchopidae; North Atlantic, South Atlantic and South Pacific each have two; the Indian Ocean has one. Some workers regard them as all of one species.