Полная версия

Sea-Birds

The rocks and coral reefs of Bermuda, which is 580 miles from Cape Hatteras, the nearest point on the United States mainland, support an interesting little community of sea-birds, which consists of the northernmost outposts of the breeding population of an otherwise completely tropical species, the white-tailed tropic bird Phaëthon lepturus, besides the common tern, the roseate tern, possibly the Manx shearwater Puffinus puffinus, Audubon’s shearwater, and the cahow Pterodroma cahow, thought to be extinct for many years.

It is in the Bay of Fundy, then, on the borders of the U.S. and Canada (Maine and New Brunswick) that the northern birds really begin. Here in burrows in the island rocks nest the southern elements of the rather small Atlantic population of Leach’s petrel Oceanodroma leucorhoa. Here, too, are the representatives of the northern race of double-crested cormorant, which are separated by a gap of some hundreds of miles from the geographical race of the same species belonging to Florida and the Carolinas.

Other birds which come on the scene between Cape Cod and the Bay of Fundy are the great black-backed and herring-gulls, Larus marinus and L. argentatus, which are now quickly spreading south down the coast, and the arctic tern Sterna paradisaea, which still nests as far south as Cape Cod. If we move north to the Gulf of St. Lawrence, we can also bring in an outpost population of the European cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo, the ring-billed gull Larus delawarensis, which is very closely related to our common gull, the common guillemot Uria aalge, and, rather surprisingly, an arctic species, Brünnich’s guillemot Uria lomvia, whose breeding distribution extends from the Magdalen Islands via Newfoundland and Labrador to the High Arctic There is a curious relict population of the Caspian tern also here. In many ways the Gulf of St. Lawrence has arctic properties and there is, as we have seen, a very steep gradient in water temperature at its mouth, at the convergence of the west wind drift and the Labrador current. Here we find the southern outposts of the largest temperate North Atlantic sea-bird, the gannet Sula bassana—though the majority of its breeding-population is found on the other side of the ocean; and we meet our first kittiwakes Rissa tridactyla.

In structure the coasts of the Atlantic right round from Maine via Nova Scotia, the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Newfoundland, Labrador, Greenland and Iceland to Britain, have a good deal of similarity. They have a fairly even supply of estuaries, inlets, beaches, sands, cliffs, skerries, stacks and islands, and it is probable that the distribution of no sea-bird is seriously limited by lack of suitable nesting sites.

There are two inland species of North American dark-headed gull, Franklin’s gull Larus pipixcan, and Bonaparte’s gull L. philadelphia, neither of which breeds near the coast.

From the Gulf of St. Lawrence, via Newfoundland, Labrador, Greenland and the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, we find a gradual disappearance of the temperate, sub-arctic and some low arctic species as we progress towards the shores where the sea is still near-freezing in July—the true High Arctic. In Newfoundland we reach the limit for breeding gannets, ring-billed gulls and common terns, and perhaps also Caspian terns. The Leach’s petrels breed as far as Newfoundland Labrador, but no farther, and it is doubtful whether the double-crested cormorant now breeds as far. South-west Greenland is less ‘arctic’ than opposite parts of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago at the same latitude; and it is not surprising that some species extend beyond Labrador to West Greenland, though not to Baffin Island and the other Canadian islands. Such species are the razorbill and common guillemot, the latter having only one small colony in West Greenland. The European cormorant extends to West Greenland and previously had a small outpost in Baffin Island, from which it has now disappeared, and it is also extinct in Newfoundland Labrador, after much human persecution. The puffin does not breed in the Canadian Arctic but goes far north in Greenland where it is of a distinctive, large arctic race.

Species which extend in breeding-range all the way from Newfoundland to Arctic Greenland and Canada are the herring-gull, great black-back, kittiwake, arctic tern and black guillemot. All these except the blackback reach the High Arctic, if we regard the Iceland gull Larus argentatus glaucoides, as a herring-gull, as we think we should.

The glaucous gull Larus hyperboreus, does not now breed in Newfoundland, but nests commonly from Newfoundland Labrador all the way to the High Arctic, as does the arctic skua Stercorarius parasiticus; two other skuas, the pomarine S. pomarinus, and the long-tailed skua S. longicaudus, do not breed in Labrador, but farther north in both Canadian and Greenland Arctic. On the west side of the Atlantic-Arctic the fulmar Fulmarus glacialis, breeds no farther south than Greenland and Baffin Island, although it nests south to about latitude 50° north on the east side of the Atlantic.

This leaves the three High Arctic sea-birds of the West Atlantic for consideration—the little auk Plautus alle, Sabine’s gull Xema sabini, and the ivory-gull Pagophila eburnea. All three breed in the more northerly parts of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago and Greenland, though the first may not have more than one colony west of Baffin’s Bay. Sabine’s gull is a rare bird that often nests in arctic tern colonies. The ivory-gull is the most northerly bird in the world in the sense that it breeds nowhere south of the Arctic Circle, but as far north as the land goes. The extraordinary, rare, Ross’s or rosy gull Rhodostethia rosea, which normally nests in the aldergroves of some north-flowing rivers of eastern Siberia, has once bred in Greenland.

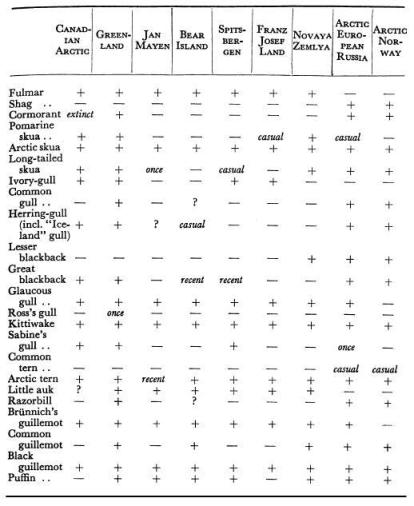

The breeding sea-birds of the lands and islands north of the Arctic Circle belonging to the Atlantic or the Atlantic section of the Arctic Ocean.

With the exception of a few gulls, sea-birds entirely desert the arctic regions bordering Baffin’s Bay and Davis Strait in October and do not return until April. From no other part of the northern hemisphere is there so great a withdrawal of sea-birds to avoid a period of inhospitable climate.

The eastern arctic islands—Jan Mayen, Bear Island and Spitsbergen, Franz Josef Land and Novaya Zemlya, which lie across the Polar Basin where it abuts on the North Atlantic, have a very similar breeding sea-bird community to that of Greenland, though none has so many members. We can best make this comparison in the form of a table, adding columns for the Canadian Arctic, Arctic Russia-in-Europe and Arctic Norway. (see here)

We now come to the seabird community of Iceland, Faeroe, the British Isles, Scandinavia, the Baltic, and the North Sea and English Channel. This community is very homogeneous, considering the range of latitude over which it is spread, though there are some members which do not reach the south end of this range and a few which do not reach the north. Among the species which are found over almost the entire twenty degrees of latitude are the Manx shearwater, the storm-petrel Hydrobates pelagicus, the gannet, the shag Phalacrocorax aristotelis, the cormorant, the herring-gull, the lesser blackback Larus fuscus, the great blackback, the black-headed gull L. ridibundus, the kittiwake, the common and arctic terns, the razorbill, the guillemot, and the puffin. Species which occupy the more northerly parts of this temperate European stretch include the great skua Catharacta skua, and Leach’s petrel (Iceland, the Faeroes and Britain only), the fulmar, the arctic skua, and the black guillemot. The glaucous gull, little auk and Brünnich’s guillemot breed (in this part of the Atlantic) only in Iceland.

There is a central group of sea-birds which breeds neither as far north as Iceland nor as far south as Atlantic France; this is headed by the common gull Larus canus, and includes also the little gull L. minutus; its other members are terns, the whiskered tern Chlidonias hybrida (only casual, in Holland), the black tern C. nigra, the white-winged black tern C. leucoptera (casual only), the gull-billed tern and the Caspian tern. The populations of all these terns are low, and only two of them (black and gull-billed) have recently bred in Britain, and that casually; their headquarters lie between Holland and the South Baltic. The Baltic Sea, though it has as many breeding terns and gulls as any other part of this stretch of the east Atlantic, lacks tubenoses and has no gannets, shags, kittiwakes or puffins. The long-tailed skua has a somewhat specialised breeding distribution in Lapland, mostly inland. The remaining birds of this temperate stretch of the east Atlantic breed from Britain, the North Sea or the Baltic south beyond its limits; they are the roseate, little and Sandwich terns. Britain is the European headquarters of the roseate tern.

About half the members of this east and north Atlantic temperate sea-bird community are truly oceanic; that is, they may be found in mid-ocean, up to the greatest possible distance from land, wherever there are suitable feeding waters. Storm-petrels, Leach’s petrels and fulmars are the oceanic tubenoses of this community, and we now find that the Manx shearwater also has a right to be considered oceanic. Among the auks the dovekie and Brünnich’s guillemot from the north join the puffins, razorbills and guillemots in ocean wanderings. Here, too, are found all the four skuas of the northern hemisphere and one, but only one, gull—the highly specialised kittiwake. In the waters a hundred fathoms deep or less, that is, on the so-called continental shelf, we find all the birds previously mentioned, together with the gannet, the black guillemot, and gulls of the genus Larus—the great blackback, the lesser blackback and the herring-gull. Once we are within sight of shore quite a number of species are added to our list, and the tubenoses, except for the Manx shearwater and fulmar, drop out. Here are the terns, the black-headed and common gulls, and also the cormorant and shag, the one haunting mostly seas in sight of sandy shores, and other seas in sight of rocks.

By far the most impressive of the sea-bird haunts are the breeding cliffs, where the different species are zoned vertically as well as horizontally. Whether the rocks be volcanic or intrusive or extrusive or sedimentary, we are sure to find Larus gulls breeding on the more level ground a little way back from the tops of the cliffs—fulmars on the steeply sloping turf and among the broken rocks at the cliff edge, puffins with their burrows honeycombing the soil wherever this is exposed at the edge of a cliff or a cliff buttress, Manx shearwaters or Leach’s petrels in long burrows, storm-petrels in short burrows and rock-crevices, razorbills in cracks and crannies and on sheltered ledges, guillemots on the more open ledges where they can stand; perhaps gannets on broad flat ledges or on the flattish tops of inaccessible stacks, cormorants with their nests in orderly rows along broad continuous ledges, shags in shadowy pockets and small caves and hollowed-out ledges dotted about the cliff, kittiwakes on tiny steps or finger-holds improved and enlarged by the mud-construction of their nests, tysties or black guillemots in talus and boulders at the foot of the cliff. These wild, steep frontiers between sea and land are exciting and beautiful. They probably house larger numbers of vertebrate animals, apart from fish, in a small space, than any other comparable part of the temperate world.

Not many sea-birds of the east Atlantic do not breed on cliffs; but the skuas nest on moors, and the terns and black-headed gulls nest on sand and shingle. Many of the Larus gulls, and recently the fulmar, are catholic in their taste in nesting sites, and may be found on moors and even sand dunes. Quite a large number of sea-birds can be inland nesters, even including tubenoses. Fulmars now nest up to six miles inland in Britain, and many of the Larus gulls at much greater distances. The black-headed gull, in particular, is often a completely inland species, since some individuals nest in England as far as they can from the sea, e.g. in Northamptonshire, and may never visit it except in casual search for food.

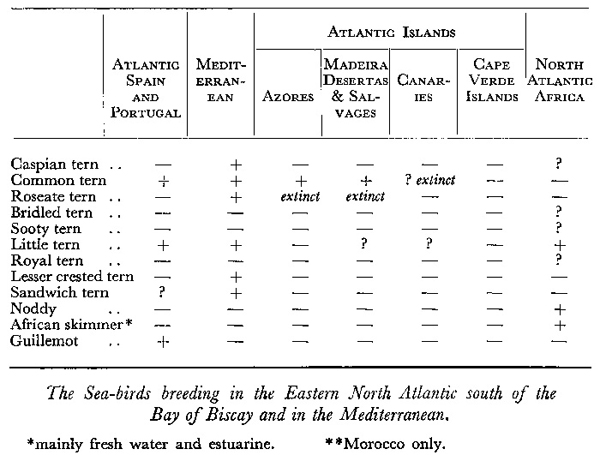

As we go south along the Atlantic seaboard of the Old World we leave behind in the Channel Islands and Brittany the last elements of certain temperate cliff-breeding sea-bird species—the gannet, lesser blackback, great blackback, arctic tern (only a casual breeder so far south), razorbill and puffin. South of the Bay of Biscay we encounter a large sub-tropical and tropical community of about forty species (a few of which belong to sea-bird families but which have become river-birds or inland birds), which is distributed in four main geographical regions—the Lusitanian coast (the Atlantic coast of Spain and Portugal), the Mediterranean, the Atlantic coast of Africa north of the equator, and the Atlantic Islands. These last comprise the Azores, Madeira (to which pertain the Desertas and Salvages), the Canaries and—near the equator—the Cape Verde Islands. Many species breed, of course, in more than one of these regions, though only the herring-gull (rather doubtfully the little tern and cormorant) breeds in them all.

Of the species in the table, the crested pelican Pelecanus roseus, the pigmy cormorant Haliëtor pygmeus, the Mediterranean black-headed gull Larus melanocephalus, and the lesser crested tern Thalasseus bengalensis breed on no North Atlantic shore, and the rare slender-billed and Audouin’s gulls, Larus genëi and L. audouinii, are primarily Mediterranean species. It will be noted that three tubenoses have established themselves in the Mediterranean, but that no less than eight species breed in the Atlantic Islands, which have a greater variety of species of this order than any other part of the North Atlantic.

The distribution of breeding sea-birds on these coasts is best illustrated in tabular form :

Of the four main groups of these Atlantic islands, Madeira and the Cape Verdes have probably the largest sea-bird communities, with ten or a dozen species each. One tubenose, the North Atlantic great shearwater, Puffinus diomedea, nests on all of them as well as on the Berlengas of Portugal. Bulwer’s petrel, Bulweria bulwerii, and the little dusky shearwater, Puffinus assimilis, also nest on all four island groups. The Madeiran fork-tailed petrel, Oceanodroma castro, nests on all but the Canaries. The Manx shearwater nests on the Azores and Madeira, but not yet farther south. The little storm-petrel reaches south to the Canaries (although in small numbers and probably to these Atlantic islands only). The rather rare soft-plumaged petrel, Pterodroma mollis, is believed to nest on Madeira; it does so on the Cape Verdes. The beautiful frigate-petrel, Pelagodroma marina, breeds on the Salvages (which belong to Madeira but are nearer the Canaries), the Canaries and the Cape Verdes.

The red-billed tropic-bird, Phaëthon aethereus, the brown booby and the frigate-bird (man-o’-war bird) do not appear farther north than the Cape Verdes. Here the cormorant, which had dropped out in Morocco, reappears as a new race, primarily South African. The bird communities of these islands are only moderately well-known. Most of the sea-birds nest on rocks whose comparative inaccessibility has been both a temptation and a deterrent to the visiting ornithologist. As for the coast of West Africa and the islands lying close to it, no organised investigation of the sea-bird communities of this difficult region has yet been made. We know that one group of species breeds on the Atlantic African coast to Morocco, but no farther south—the shag, herring-gull, the whiskered tern, probably the gull-billed tern, possibly the slender-billed gull. Farther south both white and pink-backed pelicans, Pelecanus onocrotalus and P. rufescens, and the grey-headed gull, Larus cirrhocephalus, reach the tropical sea-coast in some places, and the brown booby nests on at least one island off the coast of French Guinea. The Caspian tern, whose world distribution is, to say the least, peculiar, may have breeding stations on this coast, and the little tern, which we had left behind in Morocco, reappears as a separate race on the coast and rivers of the Gulf of Guinea.

The African darter, Anhinga rufa, reed-cormorant, Haliëtor africanus, and the African skimmer, Rynchops flavirostris, haunt the rivers and in places reach the coast; but they are not sea-birds: and on islands in the Gulf of Guinea the noddy and the white-tailed tropic-bird, Phaëthon lepturus, breed. It is suspected that the frigate-bird may nest on this coast, but its breeding-place has not been found. Neither has that of the bridled tern, Sterna anaetheta, or the sooty tern, S. fuscata, although both species are seen in considerable numbers. There is at least one other riddle: a population of the royal tern, Thalasseus maximus, haunts almost the whole coast of West Africa from Morocco to some hundreds of miles south of the Equator. Systematists have separated it from the West Atlantic population as a subspecies (albidorsalis), on valid differences, and it does not appear to leave this coast, yet no ornithologist has yet seen its nest or even its eggs.

Only in the tropical parts of the Atlantic are there still these distributional queries. In the temperate and arctic zones the breeding places of the birds are well-known and described. And with this little mystery we conclude our tour of the Atlantic, for we are back on the equator and can strike west to the St. Paul Rocks, where we began.

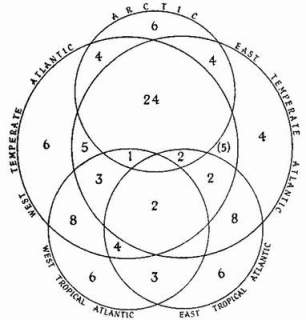

FIG. 2a The breeding sea-birds of the North Atlantic, arranged by five geographical regions. No species breeds in more than four. Number of species; see opposite page for actual species

The sea-birds of the North Atlantic can be listed in the form of a table (Appendix, see here), and plotted according to which parts of the ocean they breed in, in the form of a diagram (Fig. 2). For the purpose of completeness, the secondary sea-birds have been included, those belonging to families whose fundamental evolution has probably been non-marine (like anatids and waders) or which are only sea-birds in winter (divers and grebes). Only the more important of these are on the diagram, and they are not otherwise treated in this book. It is interesting that more than half of them are northern ducks which winter at sea, though usually within sight of shore.

It must also be pointed out that several species belonging to the families of primary sea-birds have secondarily taken to life inland, on rivers, or on estuaries, and may reach the sea only incidentally or not at all. Certain West African species, in particular, are river-birds (the pelicans Pelecanus onocrotalus and P. rufescens, the reed-cormorant Haliëtor africanus, the darter Anhinga rufa, the skimmer Rynchops flavirostris). The terns of the genus Chlidonias are primarily lake and marsh species throughout their range. In North America the gulls Larus pipixcan and L. philadelphia are purely inland species in the breeding season, and the tern Sterna forsteri and the pelican Pelecanus erythrorhynchos almost so. In South America the terns Phaëtusa simplex and Sterna superciliaris are purely river-species.

FIG. 2b Actual species. Arrows point to replacement species or to nearest ecological counterparts

One hundred and eleven species of primary and thirty-two of secondary sea-birds have been identified by competent observers at sea or on some shore in the North Atlantic since 1800: a total of one hundred and forty-one. Of these one primary sea-bird, Alca impennis the great auk, and one secondary sea-bird, Camptorhynchus labradorius the Labrador duck, are now extinct. Of the survivors, eighty-two primary and thirty secondary sea-birds actually nest, or have nested, on or near a North Atlantic or Mediterranean shore or a shore of that part of the Arctic (north of the Circle) that communicates directly with the North Atlantic (this brings in six arctic species: ivory-gull, Ross’s gull, little auk, white-billed northern diver, brent-goose and Steller’s eider). Two further species (Larus pipixcan and L. philadelphia, see table) are purely inland breeders.

Most remarkably, the number breeding on the Old World and New World sides is almost exactly the same. We can derive the following summary of breeding-species from the Appendix; the totals include the two North American purely inland species, and the two extinct species. Doubtful (“?” in the Appendix) and casual cases are deliberately included—most of them are from tropical West Africa north of the equator where the breeding of the species in question seems likely but, owing to the scanty exploration of the coast, is not formally proved.

We can see that if we add the six purely arctic breeders to those species which are common to both east and west sides of the North Atlantic, we have fifty-five, out of a total of 116, or about half. Of the remaining sixty-one species, 24 breed only on the west side of the North Atlantic, four on the west side and in the Arctic; and six purely on the east side, and seven on the east side and in the Arctic. Those on the east side include four ‘sea-birds’ which breed in the Mediterranean area but not in the North Atlantic (the crested pelican, pigmy cormorant, Mediterranean black-headed gull and the lesser crested tern).

The general conclusion is of considerable ecological interest, showing how exactly the sea-bird communities of both sides reflect one another. Although only about two-thirds of the members of the community on one side of the Atlantic are found in that of the other, the species comprising the remaining third ‘balance each other’ and occupy very much the same ‘niches’ or places in nature. Opposite species which pair off by occupying similar niches are grouped together in the list in the Appendix, see here.

A NOTE ON NON-BREEDERS AND CASUAL WANDERERS

Apart from these 116 breeders, the limbo of twenty-six primary sea-birds and one secondary sea-bird (the spectacled eider Somateriafischeri, which has been recorded twice in Norway, though it breeds on the other side of the Polar Basin) consists of casual wanderers, with three remarkable exceptions. These are all tubenoses (two shearwaters and a storm-petrel) which breed in the southern hemisphere but which cross the equator in large numbers to ‘winter.’ The most familiar of these in Britain is the Tristan great shearwater Puffinus gravis, which is rather similar, and certainly closely related to the heavier North Atlantic or Cory’s shearwater, P. diomedea. Incidentally we suggest confusion between the two would be reduced if P. diomedea were consistently called ‘North Atlantic shearwater’ and P. gravis ‘Tristan great shearwater’—not just ‘great shearwater.’