Полная версия

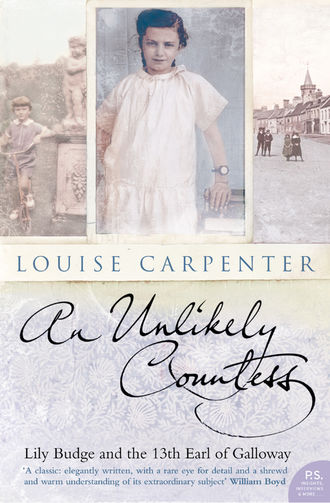

An Unlikely Countess: Lily Budge and the 13th Earl of Galloway

Although Lily was already tall, taller than Rose and Etta, she was still a child, not yet built for the physical labour expected of her. Life was now dominated by loneliness and hunger. Had she been sent to a large estate, she would at least have experienced the hierarchical but friendly bustle of life below stairs as well as the relief of regular, sustaining meals. Instead she grew paler and thinner and her hands began to crack. When she was not working she would lie on her bed in the attic and fantasise about ways of making Sis see sense, but we have her word that Sis ‘turned a deaf ear’ to this misery. When Lily made her weekly pilgrimage to North Street, she went straight to ‘my beloved Hannah’, who sympathised but, like Papa, wisely refrained from facing Sis head on.

In time Rose and Lily would prove themselves extremely adept at bolting from Duns. For now, Lily tried to please her mother and her mistress, and wrote later, ‘Although I wasn’t happy, I did my job properly, in fact, they called me Miss Tidy, no one could find anything after I had tidied a room.’ And yet she possessed an instinctive independence that prevented her from accepting her prescribed lot, a tension that was always to complicate her life. Her compliance was short lived. ‘With help from no one,’ she wrote later, ‘I took the initiative and ran away.’ It was 4 a.m. when she climbed out of a window. ‘But’, she added, ‘I hadn’t used much imagination.’ She reached North Street by dawn and no sooner had she knocked on the door and encountered Sis’s fury than she was walking the same road back. Her mistress took her back because of her age, her insecurity, and, no doubt, because she was cheap. A week later Lily bolted again, this time with the hope of travelling to London. She left in daylight, by the same downstairs window, and took the road out of Duns, which she hoped would lead to London eventually. It was a ridiculous plan – she had no food and hardly any money – and once on the road, it occurred to Lily that her ambition was beyond her. She lost her nerve and began to cry. When a stranger passed in his horse and cart, she accepted his offer to climb aboard and be taken home, weeping, to Sis and Papa, back, as she put it, to Duns to ‘face the music’.

Presented with such abject misery, Papa displayed uncharacteristic resolve. ‘“She is NOT going back!” he told Sis. “Enough is enough! The child is desperate.” I may add he won that round,’ Lily later wrote, with obvious relish. Sis, furious in the face of being overruled and intent on exacting some kind of punishment, sent Lily to bed without supper. Victory, though, was sustenance enough.

Within two or three weeks of returning to North Street, Lily began working in Greenlees, a small independent shoe store in the town square, and it was here, among the racks of heels and Oxford brogues, that she made the physical transition from child to young adult. The once gangling limbs were now long and coltish, and her square jaw and jutting cheekbones, quite ugly in a small child, had matured to give her an arresting bone structure. Duns had little to offer a teenage girl interested in fashion. But Lily made the most of what there was. She bought her clothes off the rack from Mrs Saban, wife of the butler at Manderston (her wages of seven shillings and sixpence for a sixty-hour week could not stretch to Aggie Johnson, the dress maker). When Betty, daughter of the town’s one barber, opened a small room in her father’s shop, Lily allowed her to cut off her hair and style it in the marcel wave using her new iron tongs heated up over the fire (electricity did not arrive in Duns until 1936, so even the dentist operated his drill by foot).

Mr Thomson’s school productions began winning prizes again. One in particular – Raggle Taggle Gypsies – made it to the festival finals in Edinburgh until it was discovered that the ‘leading man’ – he with the marcel wave – was in full-time employment and the cast was disqualified. ‘Much to my disappointment,’ Lily wrote, ‘my acting days had come to a halt – much to the relief of my mother, I may add.’ Despite this, there are two periods of Lily’s life where photographs record genuine happiness. The years between sixteen and nineteen are the first and the year immediately after her marriage to Randolph is the second. ‘Life was good,’ she remembered of her adolescence. She was between roles – no longer a child completely under her mother’s rule, and yet not quite a woman with responsibilities of her own. She still gave Sis her earnings, but her pocket money was raised to half a crown. ‘I felt rich indeed.’

Sis’s disdain for pleasure had abated with age, but she permitted certain excesses of youth provided they were experienced within the confines of the church. By now Lily was a committed Sunday School teacher, and a regular on the Christ Church picnics and camping trips by the coast. She looks happy enough in the photographs, but being constantly in the presence of Him must have had a sobering effect, and only at the rare ungodly events that Sis allowed her to attend, dances at the Town Hall, the Drill Hall, and the Girls’ Club, could she relax completely. There, she was more flirt than church mouse.

Sis, Papa, and Etta, not to mention the sensible and hardworking Alice Brockie, now on the cusp of becoming a nurse, came to rue the day that John David Millar walked into Lily’s life. Another forty years would pass before Lily’s friend, Lord Lauderdale, musing on marriage, would comment that romantic matches are often dictated as much by the needs and insecurities of the choosers as the merits of those chosen. Lily met Jock, as he was called, at a dance. He arrived, as usual, revving his motorbike with a cigarette hanging from his lips.

A dance in Duns was a hot ticket. The most upmarket were held in the Girls’ Club, a hostel housing young ladies from outlying areas in weekday employment, for the sum of £1 per week. The rules by which Miss White ran her establishment serve as a succinct metaphor for the aspirations of many Duns mothers. Only certain boys were allowed inside. The son of Lady Miller’s secretary at Manderston was one; the son of the Manderston butler was another. These boys, associated by proxy with the gentry, were considered safe, ‘a cut above’. Jock Millar on his motorbike would certainly have been a cut below. (Although his grandfather had been a ship owner in Dundee, his father had been cut off after falling in love with a servant girl.) He worked as a butcher in Veitch’s, the most prestigious independent grocers in Duns Town Square, where every morning he could be seen neatly arranging Mrs Veitch’s meat on small trays in the window. He had orange hair, a large forehead, and biggish ears. All this, combined with the apron, did not make him an obvious Duns Don Juan. But he dressed in sharp three-piece suits and had a way with women.

There were three things about him that attracted Lily: other girls wanted him; he was older and therefore more sophisticated; and, most alluring of all, he represented danger. He took her virginity in the fields outlying Duns and afterwards she climbed on the back of his bike and roared home to Sis, revelling in her act of defiance. Being with Jock, confident, desired, fast Jock, provided her with attention and physical affection – always in short supply at North Street – as well as security by association. Lily’s fatal error was to mistake the euphoria this gave her for love. Did Jock love her back? There are photographs of them lounging lazily in fields, he with one arm draped casually round her shoulders, the other round the plump and beaming Etta. Lily looks to have swallowed a happy pill. Jock, too, appears to be enjoying himself, but if he did love her, he had a novel way of showing it, for many more women continued to climb aboard the back of his bike. Duns being what it was, none of this escaped comment.

In February 1936 Lily became pregnant. The Miller family had by now moved from North Street to staff quarters adjacent to a large house in Langton Gate owned by Major Dees, a local solicitor and pillar of the community. Papa was his chauffeur and would sit bolt upright behind the wheel of Major Dees’s racing green Bentley. Occasionally the Major could be glimpsed in his tweeds, sitting in the back. If the scandal of Lily’s pregnancy unsettled her parents’ new-found respectability, her mother did not buckle in the crisis. Intuiting that her daughter was about to saddle herself with a bad bet – Sis was naturally distrustful of men, but she particularly loathed J.B., as she called him – she made herself clear. Lily must keep the child, but not the man. She would help bring it up. Lily was horror-struck. Nursing a child under her mother’s instruction while Jock went off with other women, leaving her behind, had limited appeal. She wanted to escape from her mother, and besides, she felt herself to be desperately in love.

Rose had long since left for Edinburgh, where she was busy making her own mistakes with men. Etta, on the other hand, heading for confirmed spinsterhood and growing ever more homely and cosy, was deeply shocked by Lily’s news. Paradoxically she did the most to spread it around, reasoning that scandal was best heard from source. It was a choppy time and somewhere in its midst Jock decided to do the decent thing. Lily was thrilled but we can be less sure of Jock’s true feelings.

Meanwhile Lily had lost her looks, almost overnight. By the time her wedding day arrived, she was gaunt and skeletal. The cause was lipodystrophy, a little-known syndrome that can cause fat deposits or strip areas of body fat and redistribute them elsewhere. In the worst cases, the sufferer is left with ‘a buffalo hump’, a Quasimodo-like pad of fat on the back of the neck. At first, Lily thought only that she was losing weight. But the muscle tone in her face continued to fall away and the wastage travelled down to the top half of her torso. Her face changed shape and her cheeks caved in. Her eyes now appeared even bigger. She had lost her youthful bloom. She had always been tiny – at dances boys had called her Pocket Venus on account of her eighteen-inch waist – but now she looked ill. ‘[I] tried everything I could to put on weight … I didn’t have much success.’ It was a devastating and cruel illness, all the crueller for the time it chose to arrive. It was identified at the local hospital but the doctor was at a loss. He had no idea of its cause and even less idea of a treatment. He sent her away with an apologetic shrug. She stopped looking in the mirror and began padding out her bra. Marriage and a child could only boost her dented confidence.

On 1 June 1936, at eight in the morning, in a ceremony at Christ Church conducted by the Reverend Richard Ford, Lily’s name changed from Miller to Millar. All her early hope and ambition was now transferred to her future family. Her wedding dress was fitted at the waist with a simple A-line skirt to the floor. She wore a matching bolero jacket and a headband, and carried a large bunch of wild flowers. Etta wore a loose, sack-like bridesmaid’s dress. Sis wore black and a grimace while Papa spent the day pensive and unsmiling. Photographs were taken in Major Dees’s garden. There was no honeymoon and no big party. Lily went straight into married life, eleven grim years of it, beginning in Galashiels where Jock had a new job as a travelling grocer. His van was his freedom, a getaway car.

John Brebner Millar Junior arrived on 9 November 1936, shortly after Lily’s twentieth birthday. His birth was the most important event in her life so far and it marked the beginning of the end of her marriage. Jock felt trapped. He began returning home long after dark and sometimes not at all. In that first year Lily spent miserable hours pacing the streets of Galashiels looking for his van. Her plan had backfired. The apparent lack of love she had from her husband only intensified the love she gave to her baby. Brebner (they dropped the John) filled her every thought, and as soon as he began to walk she paraded him about in a miniature kilt and knee-high socks. A year into the marriage, Jock secured a job with a grocer’s store back in Duns. They found a small upstairs flat in a pokey house in Gourlays Wynd and moved back, where Sis was on hand to help and harm. Lily’s marriage difficulties quickly became family business. Now Jock and Lily quarrelled, Lily and Sis quarrelled, Sis and Jock quarrelled, and sometimes even Papa joined in. Jock felt as if everybody was against him and he was right. Very quickly the marriage descended into acts of spite and bitterness, each one outdoing the last. Lily would complain endlessly about his drinking – an echo of her mother’s preoccupation – and once even marched to the store where he worked and insisted to the manager that her husband was fiddling the books to fund his drink habit (a falsehood). In return Jock would tell her she was ugly and impossible to live with. Just when it looked as if things could get no worse, on 3 September 1939 Neville Chamberlain announced that Britain was at war with Germany.

Picking over the remains of a failed marriage is a near impossible task. All the atrocious acts, the resentments, and recriminations pile up, one on top of the other, so that in the end there is nothing left but a tangled and indiscernible mess. One thing is clear though. If the end of Lily’s marriage to Jock began in peacetime, war finished it for good. Had Jock gone away to war and returned alive, perhaps the trauma of separation and threat of fatality might have reignited their brief passion. There were conscientious objectors in the town who chewed tobacco before their medical to produce the symptoms of heart trouble or wore dark glasses to create the impression of poor, infected eyes, but Jock was declared medically unfit because of an earlier bout of rheumatic fever. He was sent to work in the boiler rooms of nearby Charterhall, one of two airfields in Berwickshire used by the RAF (the other was Whinfield, near Norham). His boilers served the quarters of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force, so he had increased opportunities to stray.

The town began to fill up with evacuees from the Scottish cities, two of whom were housed in the back of Lily’s house in Gourlays Wynd. Army camps changed the Borders landscape. The largest was stationed at Stobbs in the countryside south of Hawick, holding more than 100,000 men. The camps in Duns were much smaller but they swelled the population overnight.

Now that Britain was at war, the rules that had governed Duns for so long relaxed a little. With so many of the men away fighting, some of the women began to seek alternative stimulation. This sudden sexual liberation started with the arrival of the men from the British Honduras, brought in by the Government to cut wood. They were forward in their ways – or forward by Duns standards – and soon women began to visit them in their camp at Affleck Plantation, on the Duns Castle Estate. There is an extensive file still in existence which details how many of the local women visited the camp in secret. This led to clashes between local men and the woodcutters and raids, during which women were found in the bunks. Their names and ages are listed in the file. Eventually, the camp was closed to prevent civil unrest.

On 1 April 1940, Lily gave birth to her second son, Andrew. Unlike with some of the other wives, there was no suggestion of impropriety (Duns today has a small percentage of mixed race adults, conceived during the period with the woodcutters). She was twenty-four, although photographs of her at the christening give the impression of a woman almost twice that age. Life had become rather a strain. The second baby did not bind Jock and her together but instead drove them further apart. Jock had taken a mistress, a WAAF he had met at work with whom he felt himself to be truly in love. This heady conviction only made him even more resentful of his wife. Lily leant constantly on Papa and Sis for support, regularly involving them in her battles with Jock so that he felt cornered, persecuted, and doubly justified in erring from course.

There was an unfortunate incident when Papa, who also worked at the boiler rooms, became directly involved in his son-in-law’s dalliances. Jock’s mistress misread Miller for Millar on the nightshift rota and dressed only in a raincoat, disrobed, and thrust herself onto the old man’s lap in naked glory. The next day Papa threw a punch at Jock, and they ended up struggling on the kitchen floor in a pool of water, having upended the kettle and knocked over pans, a grisly spectacle played out in front of Sis, Lily, and the children. The fight was probably the most unpleasant incident in the course of Lily’s marital breakdown, but the scraps over the tiniest matters were more exhausting and destructive. They argued violently about everything – even about how best to peel an orange.

In 1942 the town changed shape again. Two thousand soldiers from the First Polish Armoured Division arrived and were placed in another camp on the edge of the town. The Poles were every bit as alluring as the woodcutters. As they drove their tanks through the town, the officers played to the crowd. The dances continued at the town hall, but with blacked-out windows, and when the women passed them in the streets, all giggles and sly looks, the troops bowed and clicked their heels and made to kiss their hands. Some of the officers wore hairnets after washing their hair, and their cologne was considered very avant-garde. The women, particularly those who were single, gasped and swooned. While all this was unfolding, the older Duns men such as Papa, who were protective and even a mite jealous of the soldiers’ hold over the town’s women, sat around grumbling about how the tanks were smashing up their pavements.

At some stage during the war, certainly after Andrew’s birth, Lily fell ill. Doctors suspected that she had contracted tuberculosis. She was isolated immediately (no doubt to Jock’s infinite relief) in Gordon hospital, where she remained for five months, beset by self-pity. Brebner and Andrew went to live with Sis. It is perfectly true that for a young woman Lily had experienced a good deal of bad luck when it came to her health, but it must be stated that she applied a degree of drama to her suffering that would not have gone amiss in one of Mr Thomson’s school productions. In fact as an adult woman she had lost none of her childhood propensity for dramatising and displays of heightened emotion. So far as her health was concerned, her exaggerated sense of pain had started around the time of menstruation and developed to such a pitch that even Brebner, a four-year-old boy, dreaded her monthly cycle and the attendant crushing headaches of which she complained.

This latest health setback provided Sis with ample opportunity to get back into battle position and resume her recently challenged rule over her daughter’s life. When matron eventually returned Lily home, Lily was ill-equipped to fight Sis’s declaration that she was not physically fit enough to cope with her children and the stress of Jock. There was an element of truth in this. Lily would not allow Brebner to be taken from her – her bond with him was as intense as ever – but she acquiesced on the matter of Andrew. She told herself it was temporary. But the moment Andrew stepped out of her door and into Sis’s house, temporary became permanent. He never went back.

5 Happy Days Are Coming

Randolph, about to turn eleven, had been a pupil at Belhaven for two years when war was declared. At first the school made only a few adjustments. Lights were lowered and the classroom windows were blacked out with heavy curtains. But there was another change, less perceptible to the human eye. The ethos of the school, with its severe and unbending determination to turn privileged young boys, soft and fresh from the nursery, into hard young men ready for such military schools as Harrow, strengthened further still. Mr Simms, the headmaster, made use of the icy winter weather by throwing open classroom windows during lessons. Often, the temperature dropped so severely that the boys could not help but plead for reprieve, to which Mr Simms would shout back, ‘Fusspots! If you enter the army or navy, you’ll have oodles of fresh air to contend with, no matter how cold you are!’

There were other tests of character too, which had been in place long before Chamberlain delivered his speech to the nation. Bathing, for instance, if such a word can be applied to something approaching such torture, occurred at seven every morning, when Mr Simms would walk up and down the bathrooms issuing orders to the boys to jump into baths of icy Dunbar mains water. There followed prayers and early morning drill, now laden with extra significance. The school was divided into patrols: Lions, Wolves, Woodpeckers, and Owls. Each patrol would be instructed to jump up and down, arms swinging forwards and back, up and down, and over the shoulder. There were punishments, of course, which Mr Simms liked to deliver with one of two slippers, made all the more sinister for him having christened them with childish names. ‘White Tim’ was a large rubber sports shoe he kept in the junior classroom cupboard, whereas ‘Painful Peter’ was another rubber slipper but much smaller, enabling him to carry it round in the pocket of his plus fours. Boys were constantly being thrashed over desks and tables, and their first beating was ceremoniously referred to as ‘Father’s Hand’. It was not long before Randolph received that baptism.

Randolph was probably the most unpopular, most peculiar, unhappiest little boy who had ever had the misfortune to set foot in the school. It’s hard to know what came first – his queer and disjointed ways, or Mr Simms’s reign of terror and his clear disgust at having to deal with such an odd, unresponsive and seemingly backward child. Whichever way round it was, each fed the other. The more unsettled Randolph became, the stranger he appeared to his peers, and consequently the more he was loathed. Randolph’s strangeness had its foundations in his insecurity and profound inferiority complex, but also in a certain arrogance that came from being his father’s son. Paradoxically, it would be the understanding of his birthright and its privileges that would eventually pit him first against his father, and then against the lawyers seeking to deprive him of them. Given how his personality would develop, Randolph’s greatest misfortune was to be born to a family of such achievements and to a world that expected so much of him. And yet he understood that this made him special. He was trapped between liking himself too much and too little.

Randolph admits that his behaviour in the years leading up to the terrifying, barbaric medical act performed on him as a young man, a last resort to bring about a change in him, was ‘bolshy and obstructive’. He was, he remembers, prone to alarming his peers by ‘running madly around in circles and falling down in a crazily bizarre manner, and uttering the most idiotic of monosyllables [sic]’. He was always crying and showing off, trying to get attention, which earned him the nickname of ‘a baby, a babe, a bub, or a booby’. He also continued making what he called ‘bare-bottomed noises’, so that he was regularly making the dormitory reek and infuriating matron, who would enter and ask the boys, ‘Somebody is needing a dose, Garlies, is it you? Are you stinking?’

Randolph had no friends. Not only was he considered anti-social and rather disgusting by the other boys, he also seemed to possess no particular talents, not for sport, nor patrol, nor academia. During patrol, for example – Randolph was an Owl – he flailed about at the back so that in the end Mr Spurgin, the Owls’ drill master, had to move him to the front, so ‘he could … deal with me when I failed to live up to expectations’. His academic failings hit Lord Galloway particularly hard. On one paper, Mr Simms scrawled in red pen, ‘Lack of vocabulary makes you write nonsense!’ and, as even Randolph saw, ‘Mr Sims [sic] had no use for people who wrote nonsense in translation of Latin prose or History essay questions.’

Randolph did nothing to help himself. Believing that everybody around him burnt with hatred, he went out of his way to intensify those feelings, sinking into a well of self-pity and playing up to the part of school oddball. There was nobody to whom he could turn. He thought Mr Simms a bully and a sadist (the present headmaster, Mr Michael Osborne, an old boy, remembers him as ‘a daunting dome-headed bald figure, more austere than an ogre’); Miss Simms, Mr Simms’s spinster sister, who strode around in a milky coffee-coloured tunic with matching hat and feather, was guilty by association; even the maids ‘possessed a severity that would freeze the softest hearts’. On one occasion, when his turn arrived to see the school doctor, who at the beginning of every term set up his examination bed in Mr Simms’s study, he mounted such violent protest that he was dragged screaming and kicking like a wild cat by four boys holding his ankles and wrists. During school prayers he mumbled obscenities and made silly noises. Sometimes he giggled so maniacally and with so little apparent provocation that Mr Simms shouted at him in front of the other boys, ‘Garlies, don’t behave like a lunatic!’