Полная версия

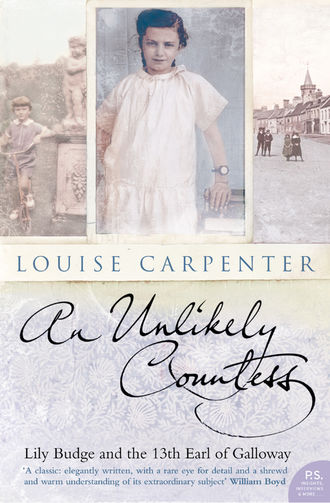

An Unlikely Countess: Lily Budge and the 13th Earl of Galloway

2. Have you a man serving at your table who should be serving a gun?

3. Have you a man digging your garden who should be digging trenches?

4. Have you a man driving your car who should be driving a transport wagon?

5. Have you a man preserving your game who should be helping to preserve your Country?

As Pamela Horn points out in Life Below Stairs in the 20th Century, in all the great houses in Scotland and England, building projects and improvements stopped, freeing up the men to fight. Gardens once lovingly tended were given over to potato growing, and much of the work on the estates, both indoors and outdoors, was carried out by women – those who did not go into munitions factories – be they former housekeepers and maids, or members of the Women’s Land Army. In the various gentlemen’s clubs, such as the Athenaeum in London, waitresses replaced the all-male staff. Mrs Cornwallis-West, the former Lady Randolph Churchill, readily embraced the change, and one hostess replaced her footmen with a set of ‘foot girls’, handsome, strapping young women in blue livery jackets, stripped waistcoats, stiff shirts, short blue skirts, black silk stockings, and patent leather shoes with three-inch heels. Most employers were less brazen. In the big hotels in Edinburgh, such as the Caledonian, staff quickly became depleted. In January 1916, conscription was introduced and Papa had no choice. He joined the Scots Greys, was wounded in the battle of the Somme in 1916, and returned home immediately. From that day on, he refused to talk of his war experiences, so his family never really knew what had happened to him – only that he came back pensioned off.

By the time Lily was born, Papa was working in the stables of the Swan Hotel in the town square, and the family was living in a cramped house in North Street, which stood directly opposite Sis’s parents’ house in South Street. The first few years of Lily’s life were spent in the shadow of a series of Colvin crises, which taxed Sis until she was red in the face with exhaustion and despair. Sis’s father was becoming increasingly demented (he would report Papa for abusing his horses but the inspectors always found them healthy and grazing happily, as round as barrels). Sis’s youngest brother, Arthur, her mother’s favourite, had not survived the war. (12 per cent of those who fought on the western front were killed, rising to 27 per cent of officers; Duns alone lost seventy-five men to the war.) Her mother, engulfed by grief, had taken to guzzling pitchers of whisky to numb the pain. She had also contracted dropsy and swollen to gargantuan proportions. She rarely rose from her bed. Those brothers still living at home, Jock and Jim, were indolent and disinclined to help. And then, in March 1918, Sis’s younger sister died in childbirth. Her daughter was also named Lily, but when it became apparent that nobody could or would care for her but Sis, the child was deposited at North Street and renamed Rose to avoid confusion.

If these burdens took their toll on Sis, she took them out on her own family. As a result Papa spent more time at the bar of the Swan, which angered Sis further, and the children learned never to approach their mother when she was in a rage or to contradict her even when they knew her to be wrong. Later Lily would write in the patchy beginnings of her memoirs, which she called No Silver Spoon, ‘Mother had a strong character … life had been hard for her as a child. Her environment hadn’t broken her as it might have done but had given her determination and a strong will, so it was she who set the rules, we were taught the difference between right and wrong, and if we broke the rules we were punished.’

The Miller girls, always impeccably dressed and groomed, with laundered smocks and over-combed hair, were as temperamentally different as their parents. In personality Lily was closer to Rose, a fiery, hot-headed girl quick to lose her temper. Rose would be the first to challenge Sis and the first to escape Duns, running off to Edinburgh at the age of sixteen. It was Rose with whom Lily clashed. Each night Etta would look on, dismayed, as her sisters tugged crossly at the oil lamp Sis had placed between them. Etta was far more bovine, round and plump and compliant, the prettiest of the three; a simple and uncomplicated child with no inclination to gaze to the horizon. Lily, with her odd, bony little face, bulging eyes, and pale knobbly legs protruding from her skirt like matchsticks, was the bridge between Rose and Etta. She possessed Etta’s gentleness and Rose’s bravado and courage. She was quixotic in attitude and agile in her movements – quite the opposite of the stolid Etta – and liked to dance and spin around, tossing her head so that her bunches twirled and bobbed about her ears. It was a show put on for anybody who would look, but the best audience was always Papa. Really, though, despite her love of dancing – ‘what rubbish,’ Sis would mutter – Lily learned early on that the most effective way of winning affection and love was by saying what people wanted to hear, and in this her acting skills came in useful.

Just before Lily’s fifth birthday, Papa was offered a position on a private estate in Ayrshire looking after hunters and racehorses, accommodation included. If ever there was a chance for Sis to slip the Colvin leash, it was now. The family packed up their possessions, piled them onto Papa’s horse and cart and set off for a new, independent life. Lily was devastated. It meant leaving behind her best friend, a wiry haired old woman called Hannah who lived in the bottom half of their council house. Hannah was an Irish immigrant, an agricultural labourer of the sort known in the lowlands as a bondager, and every night she was to be found in her bonnet and flounce sleeves, drunk in the town square, lashing out with her wizened legs at the local constable. She was, Lily later recalled, ‘very special. I have never met anyone like her since.’ It was life without Hannah, rather than leaving Duns, that Lily found intolerable. The old woman had fed her stories of taking to the road in a gypsy caravan, ‘with a horse to drive like a pedlarrman [sic], just the two of us,’ and one day went a step further, rasping hotly in the child’s ear ‘take care of those hands – one day you will become a great lady’.

Hannah might have been filling Lily’s head with bunkum, but it was to have one effect: it confirmed what Lily had already begun to feel, that she was different and wanted to escape. But climbing on Papa’s cart, squashed in next to Sis and her sisters, did not have the same appeal as bumping along in Hannah’s imaginary caravan.

Lily need not have worried. Within eighteen months the Millers were back. Annie Colvin’s health had taken a turn for the worst and, when duty called, Sis could not help but come running. Annie Colvin died on 19 December 1922, when Lily was eight years old. When the undertakers arrived, they found the corpse so heavy and large that it could not be carried down the staircase. Eventually the body was placed in a secure box and lowered to the pavement using a rope pulley. Given the location of the two houses and the fact that the horrible business must have attracted a crowd, it is likely that Lily witnessed her grandmother’s final indignity, lying on the pavement in her makeshift coffin.

The first time Lily felt what life might be like free of the Millers en masse, was at Duns Primary School, an unprepossessing low stone building close to North Street. The school was hardly a hotbed of self-expression. Once a week, for instance, the older girls were herded into line and marched over to Berwickshire High School so they could learn to cook for their future husbands and employers. There were also lessons in laundry and needlework, washing and ironing, hemming and patching, all practised on squares of white cotton and flannel. (At the end of the nineteenth century a series of codes was passed – by a government of men – that made it clear to schools that their grants would be adversely affected if such subjects were not included. Too many men had been rejected from fighting in the Boer War on medical grounds, and if the British male was puny and unhealthy, it seemed his wife’s cooking was to blame.) But compared to the atmosphere of chaos control and pleasure policing at North Street, school promised much. Lily did not warm to many of the spinster teachers – they were starchy and sharp-tongued and made her cry by thwacking maps with pointers and asking her questions she could not answer – but Mr Thomson, the headmaster, was heaven itself.

Danny Thomson was a strict, sprightly man who wore orange tweed plus-fours and liked to show the children clippings of the hybrid plants he grew in his garden. He taught academic subjects, but was especially keen on encouraging the dramatic arts. Although tone deaf, he was keen to involve his charges in the Borders Festival, a competition of performing arts in which many of the region’s schools took part. By 1928, after a string of victories that saw him banging on the school piano more fiercely than ever, in the interests of fairness, Duns Primary was asked not to enter. It was under Mr Thomson’s nurturing eye that Lily learned to tap dance. ‘I had been blessed with a good singing voice,’ she declared in later life, ‘a pair of light dancing feet and a certain ability to act.’ She became so good that Mr Thomson soon suggested she dance in shoes made for the job. Perhaps her mother would buy her some? Sis would no more pay for such frippery than she would prop up the bar at the Swan. Lily could go straight back to Mr Thomson and tell him what to do with such a ridiculous suggestion. Mr Thomson, keener than ever to ensure his star continued to sparkle, was not easily dissuaded. Shortly afterwards, he presented Lily with a pair of shoes he had found himself, cast-offs but tap shoes nonetheless. Lily ran home to North Street suffused with joy. The tap shoes entered through the front door and left through the window.

Lily was a bright child, but she had no encouragement at home, not even from Papa. Sis only valued instruction of the domestic kind. Her dream for her daughters extended to them gaining good positions in domestic service, which would, in turn, bring adequate and fair reward. ‘Mother thought it right and proper that training for anything should come from the landed gentry,’ Lily later lamented. Any attempts at studying at home were met with out-and-out resistance, which meant that Lily often left North Street in her immaculate pinafore with red eyes and half-finished homework. Given Papa’s regrets about his own undeveloped intellect, his inertia when it came to the minds of his daughters is less easy to explain. But he was a weak man and his position – or lack of it – is probably more a sign of how much he feared to contradict his wife than a belief that girls did not deserve the benefits of book work.

Aside from the wonderful Hannah, who, Lily later wrote, ‘From the day I crawled into her house as an infant … had taken me to her heart’, Lily (by now on the verge of adolescence) had one best friend. She was a bold, straight-talking girl called Alice Brockie, who arrived at Duns Primary tinged with the smell of the barnyard on account of living on a smallholding in the outlying reaches of Duns. Alice came from a good home. The family had once been successful farmers from Selkirk and her mother had employed a maid, but the post-war depression had forced her grandfather into bankruptcy and he had eventually sold the family business. Moving to Duns as a qualified specialist in Border Leicester sheep was a step down, to be sure, and it was said that Mrs Brockie was having trouble adapting. She was known as the Duchess, for her airs and graces, and it had also been noted that Alice’s sister, Bunty, walked about with a pet piglet under her armpit.

When Alice first arrived at the school, aged eleven, it was Lily who had offered friendship. It was typical of her, even then, to be drawn to someone down on her luck and apparently in need of help. Alice Brockie would never forget this first act of kindness. Lily’s friendship with her, which was to last a lifetime, was cemented by a shared dream of the future. The two girls, in their blue pinafores and bunches, would sit in the girls’ playground and plot their escape. ‘I am not going to end up a poor servant girl skivvying after other people! I will not! I will not!’ Alice would cry passionately.

They fantasised endlessly about leaving Duns. Mr Brockie might have been suffering the legacy of his father’s financial ruin, but he knew the work of Dickens, and every morning he would test Alice’s arithmetic as she sat on the side of the bath watching him shave his whiskers. He had stimulated Alice’s ambition and Lily found it to be contagious. Alice wanted to leave Duns, to leave Scotland, travel the world, and perhaps even become a doctor. Lily could not be so precise – it was thrilling to even think of a life beyond the town square, let alone decide what to do with it. All she knew for certain was that she wanted more than what Sis had in mind.

In 1928, when Lily was twelve, she began part-time work in a baker’s shop. Lily’s days now began at 7 a.m. with the collection of morning rolls to be delivered in a large wicker basket before school. The weekends were the busiest. Orders doubled and the Saturday bread run started at 6.30 a.m. The bakery paid Lily three shillings and sixpence a week, as well as a large bag of cakes and a bag of sweets, all of which she handed over to Sis, who then handed back nine pence, three of which she called ‘pocket money’. Lily, schooled in her mother’s impressive housekeeping, saved the sixpence ‘pay’. After returning home to North Street for breakfast, on Saturdays Sis would put Lily and Rose to work. The bedroom was turned out and the stairs and lobby scrubbed. When ‘the chores in the house were done to my Mother’s satisfaction’, the girls were given a wheelbarrow and sent to the sawmill over a mile away to collect wood. They made the journey twice, first for thin logs, and then for the fat ones Sis used for cooking mutton stew in her cauldron.

All chores, including cooking Sunday lunch (always stew, usually mutton but sometimes rabbit if Sis was feeling generous) had to be finished by Saturday evening. Sis refused to work on the Sabbath. She was, in Lily’s words, ‘a keen church goer and she set the pattern’. Setting the pattern included herding her girls to Bible class and then afternoon Sunday school, where Lily became a teacher, and badgering Papa to convert from the Church of Scotland to the Church of England. He complied, for a quiet life, but even the children noticed their father was not quite as ardent in his beliefs as one might expect of a church warden. ‘He went along with it all the same,’ Lily later wrote, a succinct epitaph for Papa’s general attitude to life.

The Millers worshipped at Christ Church, an Episcopalian church dating back to 1857. It is still there today, sitting high on Teindhill Green, which snakes across the top of Duns. It is surrounded on all sides by its graveyard and inside are the usual memorials to those singled out for special attention. Lily, in her best dress, became familiar with these as she sat in the third pew from the back where she was squashed in next to Papa, Sis, Etta, and Rose. The front pews were filled by the Berwickshire gentry, the descendants of those remembered on the walls: Mr and Mrs Hay of Duns Castle, Papa’s old employers; Captain Tippins; Lady Miller from Manderston and the incumbents of Charterhall. The congregation encompassed the very rich and the very poor, so Sunday service gave Lily her first taste of the class divide. ‘They have such loud voices,’ she would whisper to Papa. ‘Why do they shout at each other like that?’

For the other six days of the week, the gentry, apart from the Hays, remained hidden on their estates or in London. Their children were educated either at boarding school or at home. Errands were run by staff. Occasionally a car would purr through the town and the men would tip their hats if a lady were inside, but these sightings were akin to spotting a rare bird. No sooner had they come into view than they were gone. Their homes ran along banks of the River Tweed, known locally as ‘Millionaire’s Row’. Lily, like all the other ordinary girls in Duns, was not destined to breathe such air. The closest she would come to this life of privilege was waiting at the tables, clearing the hearths, and making the guest beds, and that, according to Sis, would do quite nicely.

If Lily had dodged thinking about the grim reality of her destiny, preferring instead to dream with Alice, in 1930 she was given no choice. Turning fourteen marked the official end of her education. Sis’s project was to send her into service as soon as possible and she enlisted Etta to keep an ear to the ground for a suitable position – nothing too grand, but enough to put Lily on the first rung of the domestic service ladder (the last rung being a position with a titled family). When the day came for her to leave school, her sadness at waving goodbye to Alice and Mr Thomson was made bearable only by the fact that Sis had not yet found her a position and that she would not be leaving North Street. It was never Sis’s plan to have Lily moping about at home, so when the baker for whom Lily worked offered her a job minding his children, three-year-old Olive and five-month-old Moira, Sis was happy to let her do it. This was a temporary measure until something ‘proper’ came up.

Caring for the baker’s small children brought Lily much pleasure. She took them for long walks around town, Olive toddling along by her side and Moira peering inquisitively from the pram. Lily loved tidying and rearranging the nursery. This routine continued for a few months and Lily was ‘thrilled’ at the way things had turned out. ‘However,’ she was to recall years later, ‘mother had different ideas.’

Sis spoke endlessly about the benefits of learning from the aristocracy. In a good family Lily would be looked after and would learn to distinguish what was good taste and what was bad. Being surrounded by pictures, silverware, and fine china would cultivate her. It would be impossible to live among such beauty, Sis argued, without some of it rubbing off. On a more profound level, Sis believed the upper classes were morally ‘better’: it was as simple as that.

These ideas were backed up by a series of contemporary manuals. One, for example, A Few Rules for the Manners of Servants in Good Families, published by the Ladies’ Sanitary Association in 1895, had been in wide use during Sis’s childhood. The book makes the self-will and discipline required for a future of servitude all too clear. It is a bible of dos and don’ts, and could easily have engulfed an independent-minded young woman like Lily in a fog of inferiority. Don’t walk on the grass unless permitted or unless the family is out, and walk quietly; never sing or whistle; when you meet the mistress or master on the stairs, stand back or move aside for them to pass; when carrying letters or parcels, use a small salver or hand tray; never hand over a letter directly, risking skin contact, but place it instead on a nearby table. Another, A Servant’s Practical Guide: A Handbook of Duties and Rules for the Use of Masters and Mistresses, carries the same message. Its advice for coffee time leaves a mistress in no doubt of the kind of climate to cultivate:

The women servants stand behind the buffet, and pour out the tea and coffee. The only remark offered by servants in attendance is: ‘Tea or coffee, ma’am?’ Not ‘Will you take tea or coffee, ma’am?’ or ‘Shall I give you some tea ma’am?’ A well-mannered servant merely says in a respectful tone of voice ‘Tea or coffee, ma’am?’

Following the war, many former male and female servants had been reluctant to return to their old positions; war work had given them the taste for a more independent life. But in spite of this, post-war industrial depression and high unemployment led to a steady rise in domestic staff during the inter-war years. In the Borders, where there were large estates still operating on comparatively large incomes, domestic service never stopped being regarded as the principal source of employment for young girls.

Sis quite rightly viewed Lily’s Borders upbringing as an advantage. The Fairbairn Agency on the Edgware Road in London, for example, specialised in supplying simple Scottish maids to good English families, ‘mostly titled’. Glasgow girls were always rejected ‘as they are too rough’, as were ‘stockingless or made-up girls’. Country girls were ideal because they were so sensible, unsophisticated, and lacked the wisdom of the world, the three virtues Lily desired to be rid of. But she was given no choice. ‘So my days with the children were short-lived, and I was sent to “proper service”.’

3 Virescit vulnere virtus: Valour grows strong from a wound

On 14 October 1928 at 2.45 a.m., in a large, elegant bedroom on an upper floor of 34 Bryanston Square, London W1, the 12th Countess of Galloway, gave birth to a son and heir. The boy was christened Randolph Keith Reginald Stewart, names chosen in honour of his father, grandfather, and uncle. There was also the courtesy title of Lord Garlies, which the child would keep until his father’s death, whereupon he would succeed to the title of 13th Earl of Galloway. When Randolph arrived into the world that morning there was no indication of the troubles that lay ahead. Physically, he was perfect. Lord Galloway, the 12th Earl, could rest easy. Three years before Lady Galloway had delivered a daughter, Lady Antonia Marian Amy Isabel Stewart. Now that there was a boy the line would live on, for another generation at least.

Lord Galloway was an accomplished historian, particularly when it came to how the Earls of Galloway, one of Scotland’s oldest noble families, fitted into Britain’s history. They remain one of the main lowland branches of the Stewarts, and, in the absence of a chief, are considered by the Stewart Society, founded in Edinburgh in 1899 to collect and preserve the history and tradition of the name, to be senior representatives of the clan. If a lineage dating back to the twelfth century seemed irrelevant to a small boy born after the First World War, then it was not considered to be so by that boy’s father. Documents and articles held in the Stewart Society library bear many of Lord Galloway’s annotations and corrections. His heritage brought him great pride. He did not care for family members who chose to forget it.

The Galloway earldom has its roots in the Lord High Stewards of Scotland, whose line also produced the Stuart monarchs. When David I gave the 1st High Steward, Walter, his position, he effectively made him Scotland’s equivalent of Chancellor of the Exchequer and occasional army general. It was the third High Steward – also called Walter – who turned the title into his family name, which continues to this day. An unbroken male line descends from Sir John Stewart of Bonkyl, who died at the battle of Falkirk in 1298. Two of his sons fought alongside Robert the Bruce and were rewarded with lands. Their cousin, Sir Walter, later the 6th High Steward, also distinguished himself as a commander at Bannockburn in 1314. He was knighted on the battle field by Robert the Bruce and later married his daughter. Fifty years on, their son became King Robert II. In 1607 James I made Sir Alexander Stewart Lord Garlies. Sixteen years later he created for him the Galloway earldom. Queen Elizabeth II is a direct descendant of the royal Stewarts through the female line.

The early bravery and military inclinations of the Stewart relatives – some destined to become the Earls of Galloway – continued through the centuries, right up until Randolph’s birth. Some stood out. Lieutenant General Sir William Stewart, fourth son of the 7th Earl and Countess of Galloway, for example, co-founded the Rifle Brigade and fought in the Napoleonic Wars. His journals and papers, known as the Cumloden Papers and dating from 1794 to 1809, preserved at the family seat of Cumloden, contain a record of his achievements and include revealing correspondence from the Duke of Wellington and Lord Nelson.

Everything Lord Galloway knew and felt to be true about life derived from his family legacy. He was born on 21 November 1892, to Amy Mary Pauline, the only daughter of Anthony John Cliffe of Bellevue, County Wexford, and christened Randolph Algernon Ronald Stewart. His father, Randolph Henry Stewart, son of Randolph, 9th Earl of Galloway, had joined the 42nd Highlanders in 1855 straight from Harrow School. In his military career he survived some of the empire’s most significant conflicts. He served in the Crimea and was present at the siege and fall of Sebastopol (for which he received a medal with clasp and the Turkish war medal) and also at the Indian Mutiny, during which he was present at the fall of Lucknow (another medal with clasp). He retired, as a captain, in 1876. He was fifty-five by the time he married, fifty-six when his first son was born, and succeeded as 11th Earl of Galloway, following the death of his elder brother, the 10th Earl in 1901.