Полная версия

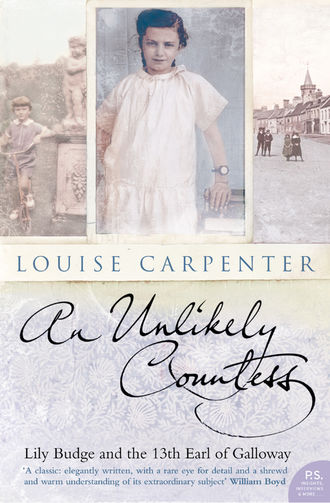

An Unlikely Countess: Lily Budge and the 13th Earl of Galloway

‘On Tuesday 12th December before dark, I had my last appointment with Dr Wilson on psychological matters,’ Randolph writes of his last week at Harrow. These last days were ‘all eaten up in the misery of unpopularity and mocking, humiliating ridicule’, but tinged with not an ounce of regret. Randolph tried to keep his departure a secret, but it somehow got out and the boys began taunting him that it was because he was stupid. At Christmas, he left, weighing 5st 11lb and three-quarters, bound for home.

Back at Cumloden his failings became increasingly domestic. The day after he arrived Lady Galloway gave him a talk, but it was to no avail. He showed himself up in the dining room and was considered ‘rude, discourteous and impolite’. On another occasion, he attempted to sweep some crumbs off the table using the floor broom. ‘In a gentleman’s house,’ Lord Galloway said, ‘one does not use the dirty brushes of servants on one’s dinner table.’

Randolph says today that everything his family did, every decision they made regarding his future, was always in the hope that it would bring about some kind of change in his personality. It is impossible to know whether that frightened, weak little boy at Harrow forgave them for this or indeed whether, at this stage, there was anything to forgive. How many parents of their generation and class would not have wanted to mould their heir for future responsibilities? Was their treatment of him simply a display of disciplined, responsible, illiberal parenting? That Lord and Lady Galloway came to rely on a string of expensive London psychiatrists shows how desperate they were becoming. There can be no doubt that Randolph’s difficulties were as hard for them to bear as for Randolph. But their desperation would eventually lead them to make a decision with far more destructive consequences than a pair of lost eyebrows.

For now, fresh hope was invested in the influence of Shane and Madelaine Chichester. As planned, on 9 February 1945, Randolph left Scotland for Farnham Station and life at The Rough. Ten days later, Shane Chichester delivered his first homily: ‘[we] discussed my psychological situation, concerning the unnecessary phobias and complexes which had bugged me. I then had a low opinion of myself yet I was too proud and conceited to accept any criticism. Concentration, that of mine was another thing which worried Shane Randolph Chichester, and when people asked me questions I too often remained silent.’

At the beginning of March Shane gave Randolph a prompt card on which he had written his pearls of wisdom:

1. There are no reasons for fear

2. Happy days are coming

3. The truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth

4. Possunt quia posse videnta [sic] – They can because they think they can

5. I shall pause and think before answering questions, then answer frankly

6. I can do all the things through Christ who strengtheneth me. Get into the stride of saying I can.

While Shane continued in his subtle and kindly efforts to correct Randolph’s personality, a specialist in psychology and psychiatry began visiting the house. Poor Cousin Shane was continually tried: ‘I entered the dining-room to pull down my brows at Shane … who then told me that he did not want to see a dark frown but a nice bright smile on my ugly face. I continued both to under and to overestimate myself.’

On V-E Day, 8 May, which Randolph describes as ‘a day of magic’, he was still at The Rough. Bolstered by the news, he moved his bed so he could lie on a platform outside his bedroom window and look up at the stars. By that August, when war ended with Japan, peace was finally restored to Britain. If only Randolph’s life could have been as hopeful. Two months after Britain’s victory he left The Rough accompanied by Lord and Lady Galloway. They were headed back to Scotland via London. Randolph was to spend a few days ‘with family and psycho-annalists’, a slip of the pen that reminds us how much Randolph’s future medical treatment would reveal about the annals of psychiatry.

6 Becoming Mrs Budge

‘By the end of the war I … had lost my husband, not in the horrors of war but to another woman in the Forces,’ wrote Lily of peacetime. Her marriage to Jock, having limped through the war years, now gave up the fight. Jock eventually left her for his mistress. Bad luck had also struck Rose. Two years after Lily gave birth to Brebner, Rose, at the age of twenty, gave birth to a baby girl called Ann, an event shortly followed by the disappearance of her husband. She married again, only to find that her new husband liked to drink. She had produced two more children (his), and the family was living in near squalor in a flat by the docks in Leith, then one of the most dangerous and run-down areas of Edinburgh. Only Etta, harbouring no ambitions to leave Duns or escape her life of domestic service, gave Sis any hope. Out of the blue she announced her intention to marry a quiet and gentle shepherd, employed on a nearby farm called Blackerston. Following the wedding, she joined him in his quarters, a wing of The Retreat, a large, round hunting lodge and, just when Sis and Lily had ruled out the possibility of Etta producing a family of her own, in 1947 she announced that, at the age of thirty-seven, she was pregnant. Nine months later she delivered a girl, also called Anne. (If there was a compensation for Etta’s comparatively uneventful existence in Duns it was that she remained married to the same man until she went to her grave.)

Lily’s single status sustained the Duns gossips, not least because another woman was involved. But Lily shrugged off the talk. Her godchild, May Millar (no relation but the daughter of Sis’s friend), then an impressionable child at Duns Primary, remembers being struck by how her godmother seemed wholly indifferent to what people were saying behind her back. She thought that this was either because Lily would not have wasted her energy on the opinions of those who did not know her, or because fresh problems had presented themselves on Jock’s departure. Money worries loomed and they consumed Lily’s waking hours. She did not expect, nor did she receive, any financial help from Jock. This left her with the sole responsibility of bringing up the boys, added to which was the worry over Andrew’s health (he had contracted scarlet fever). Sis and Papa were ‘wonderful’, Lily later recalled – ‘the only financial support I had was from them’ – but their donations could only stretch so far and it became apparent that Lily would need to find a full-time job.

Lily later wrote, ‘with a sad heart I made my way to the city’, but it must be stressed that once again her sadness was not at leaving Duns – after all, it held nothing for her any more, if it ever had – it was much more to do with Sis’s insistence that Andrew stay behind. His ear had been perforated and he was now partially deaf. He was also weak from the aftermath of his illness. As Lily observed, ‘They were still young enough to look after him and give him the extra care he needed.’ It was a decision made with his best interests at heart, but the consequences were to reverberate for years. Andrew was seven and broken-hearted. His father, as he saw it, appeared not to love him – he once shooed him away from Gourlays Wynd as if he were a stray – and now he was being left with his grandmother, who terrified him to the point of making him mute. The child adored his mother and could hardly bear the thought of her disappearing off for a new life with Brebner. But Andrew was a soft, delicate child, prone to tears, and he quietly accepted the situation. Brebner, on the other hand, created a scene. He wanted nothing more than to stay behind with his friends. As a result each looked to the other as having secured the better deal and this jealousy and resentment forced them further apart. (It was to last well into their adult years, when slowly they discovered they liked and then loved each other very much.)

Lily and Brebner arrived in Edinburgh in the spring of 1947, the inaugural year of the Edinburgh International Festival, conceived by Sir Rudolf Byng, conductor of the Glyndebourne Opera, as an optimistic and defiant response to Nazism. The plan was that she and Brebner would stay with Rose in Leith until they were on their feet. On this occasion Sis was right. A grim scene awaited them. Lily was completely unaware of the conditions in which Rose lived. As she walked up the stairwell she saw a mouse, which she thought a bad sign. She peered into the apartment with increasing dread. The walls flaked from damp and many of the floorboards were rotten or splintered. The flat had three rooms – a sitting area, a bedroom, and a kitchen, with a communal lavatory.

That night Brebner was given the sofa and Lily slept on the floor beside the cockroaches. The next morning she determined to find herself a domestic job that would get them out. She was, of course, returning to a profession she loathed, but servants were in demand after the war and needs must. By nightfall she had secured a position as a housekeeper in a large Victorian boarding house in Cluny Gardens, in the bourgeois and respectable area of Morningside, her accommodation provided. She returned to the tenement, collected Brebner and that night they slept in their new basement flat. She began her duties the next day, cleaning a house full of unappreciative students. It was an exhausting, soulless job, but it promised a modicum of stability. Brebner was enrolled in the local school, and just as their lives appeared to be acquiring a rhythm, an incident occurred that led to her tendering her notice.

It is important here to remember Lily’s propensity to over-dramatise, but then the ‘episode’ is odd enough that one wonders how she could have made it up. A student boarder had, apparently, wantonly dropped his trousers and undergarments while she was dusting. Lily’s reaction to this absurd display of masculinity (or lack of it) is telling. For all Lily’s efforts to widen her horizons, there was still a streak of the Duns prude in her. She could not possibly stay on in Cluny Gardens following such an assault on her dignity, no matter how much trouble it caused her. And so off they went again, this time to the Hotel Marina on Inverleith Row, which was managed by a one-armed man. She did not stay there long – for unknown reasons – and they then moved on to lodgings in Hillside Street, where they lived while she worked in a snack bar in the city centre, frying up eggs and bacon.

The year that followed was the most itinerant of Lily’s life. She was constantly moving in and out of jobs as she changed her mind about what was best for Brebner. She could not settle. Edinburgh then was a city of absolute contrasts – the rich and the poor, the New Town and the Old Town. The divisions and distinctions were there even in the architecture of elegant sweeping crescents and squares beside tenements black with soot. While serving up plates of food heavy with grease, she clung to her dream that Brebner would have the chance of a different kind of life. With each trying experience, the bond between them could only intensify. Andrew would later remember, poignantly, ‘She loved me, of course, I always felt that, but Brebner was number one son. She adored him. You only had to watch her face when she looked at him.’ Lily felt their connection was spiritual. Once when Brebner fell and split his head on the pavement, she recalled that ‘the pain was so intense with me, at the same moment, that I couldn’t see for a second or two’. On another occasion, when he was knocked down by a taxi, she maintained she felt a sharp pain across her chest. ‘I knew he was in trouble but could hardly breathe,’ she wrote, ‘and a few minutes later he was carried into the house, he had bruises and his ribs were broken, the doctor had to strap my ribs up too, we recovered together.’ One imagines the doctor was startled when asked to bandage Lily up, but the idea that she might have appeared comical, eccentric, absurd even, would not have occurred to her. Her feelings did not exist in half measure and for the most part she was quite unable or unwilling to keep her instincts and impulses in check.

With all the toing and froing Brebner fell behind with his schooling. When the results of his eleven plus examination were announced, Lily saw with dismay that he had failed, which brought back the memory of her own childhood disappointment. She understood immediately that if she did not take action, Brebner was in grave danger of treading her path. She had no intention of sending him to Darroch, a secondary modern, which she called the ‘the drop-out school’. Instead she enrolled him in Trinity Academy, a semi-private school. Because she could not stretch to the uniform, she joined a warehouse clothes club that offered, for a weekly hire purchase charge of five shillings, £10 worth of clothing, which covered his blazer, cap, and tie.

Lily always had an atrocious grasp of finances and her first financial embarrassment remains murky, probably because it was murky even to her. What is clear is that she overstretched herself by moving from the lodgings in Hillside Street to a flat in Leith, which, with Sis’s and Papa’s help, she hoped to buy, probably through the services of a loan shark. Sis was now as sturdy and squat as a little ox. Her face had fattened and slackened and on the end of her nose sat round, black-rimmed spectacles. Her breasts had grown to an enormous size and drooped towards her waist so that there was a balcony effect dominating the top half of her frame over which clothes strained at their fastenings. She paced about in comfortable shoes and carried her handbag tucked under her left arm, which she kept stiff at a right angle to her body. She still cooked mutton stew over the fire and gossiped in the town square. Papa, on the other hand, was as thin and wiry as ever, so that together they looked like Jack Spratt and his wife. For all Sis’s instincts to control and dominate – now regularly exercised on her grandson – and for all Papa’s inertia, they remained loyal and willing to help. Recognising Lily’s need for security, Sis and Papa gamely provided her with a deposit. Suffice it to say, the scheme went wrong. Lily could not keep up the payments, and the bailiffs arrived to carry away every piece of furniture for which she’d saved. Brebner, sleeping on balls of their clothes, contracted nephritis.

Lily had no desire to return to Duns, but Sis’s support had always come at a price. She made her feelings clear and within a few days Lily and Brebner were on a train heading towards the Berwickshire coastline. In 1949 the Millers were living in the top part of a terrace in Gourlays Wynd, bought by Sis’s brother, Jock. There were Sis, Papa, Andrew, Jock, and his brother Jim. Two years of power struggles ensued. Brebner and Andrew fought constantly, but the real battle raged between Lily and Sis.

The problem was not a new one. Sis persisted in treating Lily as though she were a child, incapable of making decisions about her life. Given the disasters that had occurred since Lily had left home, and the fact that Lily had, when it suited her, fallen back into the parental safety net, Sis had some justification in assuming Lily needed her guidance. Her failure, though, was her approach. She lacked the skills of tact or diplomacy and so her suggestions, however well-meant, were always delivered as orders. Lily felt cramped and stifled, and this fresh exposure to her mother’s domineering nature reignited all the resentments she had felt during her childhood. Had these quarrels been purely personal, a simple clash of personality, perhaps they would not have been so fierce, but what truly fanned the flames was that they often erupted over matters concerning the children. Sis had been raising infants from the age of nine and this, she believed, gave her the upper hand. There was also the indisputable fact that when it had suited Lily, she had been quite willing to leave Andrew in Duns in her mother’s care. Sis was right about this, at least. But there was no getting round the fact that Sis’s way of child rearing repulsed Lily. She was horrified by the idea of physical punishment (Sis once beat Andrew with a bunch of rhubarb), and rather than toughen her boys up, she preferred instead to demonstrate her affection. She liked to embrace them and kiss them and tell them how much they were loved. There is no doubt that Brebner was overindulged, and that Lily was endlessly overcompensating for the fact that the boys did not have a father or any semblance of family security. But beyond these unconscious motivations, Lily had discerned from her own childhood that children needed affection.

If anything could have driven Sis and Lily even further apart, it was the issue of Brebner’s education. Sis could not imagine him remaining at school beyond an age when it was compulsory. Did Lily not understand he had a duty to contribute to the household? Was she quite mad? Lily saw red on this issue – in fact she possessed no more powers of diplomacy or tact than her mother. Her boy would not face the same indignities as she had. She was going to provide him with a proper education. During the rows that followed, Jock and Jim were monosyllabic and unfriendly, and the boys continued to fight like tomcats, biting and pinching after dark and bloodying each other’s noses.

Life became intolerable. Lily decided to return to Edinburgh, this time for good. She had earnt her keep in Duns by housekeeping and by now had occupied a string of positions. These enabled her to secure a good post before she left. In 1951, she packed her bags and Brebner’s – but not Andrew’s – and boarded the train for Waverley Station. This time, the circumstances of her arrival were more ordered. She stood outside 42 Blacket Place, a large Georgian house in a sweeping crescent south of Princes Street, and pinched herself. She was to become housekeeper for the McIntosh family. Professor Angus McIntosh was Chair of English Language and General Linguistics at the University of Edinburgh. Lily’s service flat was once again in the basement.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.