Полная версия

The Conversion of Europe

Unappealing as we might find this disposition of antique citydwellers, it was one which witnessed to a massive confidence in the urban order of imperial Rome. The Christian communities of the Mediterranean world had grown up in that order, if not quite of it. They took it for granted and they were right to be confident in it. From the beginning of the Christian era in the reign of Augustus for the next two centuries the Mediterranean (as opposed to the frontier) provinces of the empire had basked in almost uninterrupted peace and prosperity: the pax romana. The public buildings of the cities and the speeches which were declaimed in them alike display a bland and soothing mastery of their respective architectural and literary techniques; symptomatic of a social order which gazed upon its way of going about its business and was pleased with what it saw. Look at me, the colonnades and arches of Leptis Magna seem to say: relax; enjoy; and it’ll go on like this for ever.

But it didn’t. In the middle years of the third century the Roman empire experienced a phase of trouble more harrowing and profound than any that had occurred since the founding of the principate by Augustus. During the half-century which followed the death of the Emperor Severus Alexander in 235 there ensued a series of short-lived and for the most part incompetent rulers. Of twenty more or less legitimate emperors – not counting usurpers – all but two died violently. The average length of reign was two years and six months. A symptom, and perhaps to a large degree a cause of this instability was the inability of government to hold the allegiance of the armies. This played into the hands of the generals, who used the troops under their command to stage coups which made and unmade emperors or to set up breakaway ‘empires within the empire’. As central control slackened, imperial income fell. To make ends meet, and in particular to try to satisfy the insatiable demands of the military and thus to purchase loyalty, the government resorted time after time to that most irresponsible of expedients, debasement of the coinage. Debasement brought in its train, as it always does, inflation. By the end of the third century the purchasing power of the denarius stood at about a half of 1 per cent of what it had been at its outset.

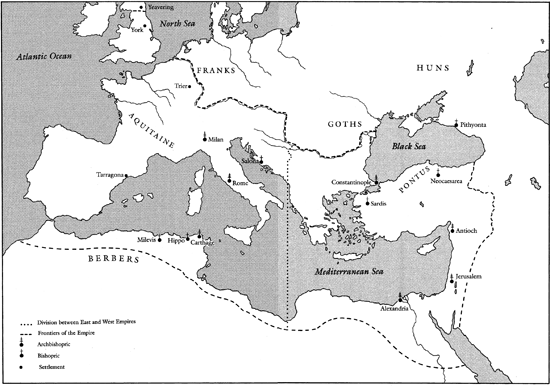

Crippled by instability, civil war, fiscal chaos – and, just to make matters worse, by intermittent outbreaks of bubonic plague – the empire was in no position to defend its frontiers. From 224 onwards the new Persian dynasty of the Sassanids constituted a well-organized and hostile presence to the east, bent upon regaining the Syrian territories which Persian kings of old had ruled. For the Roman empire, the most humiliating moment of this time of troubles occurred in 260 when the Emperor Valerian was captured by the Persians. The Germanic tribes of the Goths, settled at this period on the northern shores of the Black Sea in today’s Ukraine, took to the sea to strike deep into Asia Minor. By land, they pressed hard on the Danube frontier, launching raids into the Balkans and Greece. The Emperor Decius was defeated and killed by them in Thrace in the year 251. Along the Rhine frontier new Germanic confederations, those of the Alamans and of the Franks, took shape. In 257 they broke into Gaul to plunder it at will. Some of them even penetrated as far as northeastern Spain, where they sacked the city of Tarraco (Tarragona). Berbers along the Saharan fringes attacked the long, thin, vulnerable littoral of Roman north Africa. In far-flung Britain the construction of coastal defences witnessed to new enemies from overseas – Saxons from Germany and Scots from Ireland. One of the most telling signs of the times was the building of town walls throughout the western provinces of Gaul, Spain and Britain, furnishing defences for settlements which had never needed them before.

The third-century slide into anarchy and helplessness was arrested by the Emperor Diocletian (284–305). His stabilizing reforms, fiscal, military and bureaucratic, were continued and extended under his successor Constantine I (306–37). Their work gave the empire the stamina and solidity it enjoyed in the fourth century. One feature of these reforms was the adoption of ideas about monarchy, together with the associated ceremonies and ritual, which drew on earlier Hellenistic and Persian thinking. The principal tendency of this body of political theory was to stress the power of the ruler in matters sacred as well as profane. It would encourage the moving together of church and state and, as time went by, their near merging in the imperial theocracies of the East Roman or Byzantine empire and, much later, in its Russian heir. It was a tendency which was less pronounced in the western provinces of the fourth-century empire. This was a difference which had important implications, to which we shall return shortly. A second feature was the division of the unitary empire into two halves, an eastern and a western. Diocletian had led the way here, dividing the empire into a tetrarchy – a senior emperor in east and west, each with a subordinate emperor – as part of his reforms; a decentralization intended to make more effective the emperors’ discharge of their primary responsibility, defence. This formal structure was not maintained after his death and practice varied in the course of the fourth century, but by its last quarter the political division into eastern and western empires had become permanent. One development which helped to institutionalize it was Constantine’s foundation of a new capital city in the east, named after him – Constantinople.

A third feature of the reforms of the Diocletianic-Constantinian period was the change in the status of Christianity within the empire. Towards the end of Diocletian’s reign there occurred the last and most serious persecution of the Christian communities ever mounted by the imperial authorities. It was immediately halted by a respite. The story of Constantine’s conversion is well known but needs to be told again in outline here because it became such a potent model – indeed, a topos – of how a ruler should be brought to the faith. Constantine had been proclaimed emperor in Britain in 306. Six years later, having by then made himself master of Gaul and Spain as well, the emperor was leading his army south to do battle with his rival Maxentius for control of Italy and Africa. At some point in the course of this journey – much later tradition would locate this at Arles – Constantine saw a vision of the cross superimposed on the sun above the words In hoc signo vince, ‘Conquer in this sign’. He advanced over the Alps and down towards Rome. His troops were ordered to mark their shields with the sign of the cross. In the battle of the Milvian Bridge, just outside Rome, Constantine was victorious against all odds. The Christian God – a god of battles – had been on his side. A few months later, in March 313, the so-called Edict of Milan put an end to the persecution of the Christians.

In what sense and when Constantine became a Christian are questions that have been endlessly and inconclusively debated. In the formal sense of the word he was not initiated until shortly before his death in 337. Like many others in the early church he chose to postpone baptism until his deathbed. But his adhesion to Christianity from 313 onwards was not to be doubted. Its most enduring manifestation was in open-handed patronage. Constantine did not make Christianity the official religion of the Roman empire, though this is often said of him. What he did was to make the Christian church the most-favoured recipient of the near-limitless resources of imperial favour. An enormous new church of St Peter was built in Rome, modelled on the basilican form used for imperial throne halls such as the one which survives at Trier. The see of Rome received extensive landed endowments and one of the imperial residences, the Lateran Palace, to house its bishop and his staff. Constantinople, begun in 325, was to be an emphatically and exclusively Christian city – even though it was embellished with pagan statuary pillaged from temples throughout the eastern provinces. Jerusalem was provided with a splendid church of the Holy Sepulchre. Legal privileges and immunities rained down upon the Christian church and its clergy. The emperor took an active part in ecclesiastical affairs, summoning and attending church councils, participating in theological debate, attempting to sort out quarrels and controversies.

1. The Mediterranean world in late antiquity.

The adhesion to Christianity of Constantine and his successors with the single exception of the short-lived Emperor Julian ‘the Apostate’ (361–3) – was a development of the utmost weight and significance in Christian history. All sorts of relationships were turned topsy-turvy by it. From being a vulnerable, if vibrant, sect liable to intermittent persecution at the hands of the secular authorities, Christians suddenly found themselves part of the ‘establishment’. The end of persecution meant that martyrdom must thenceforward be found only outside Christendom or be understood in a metaphorical rather than a literal manner. Christian bishops were no longer just the disciplinarians of tightly organized sectarian cells but rapidly assimilated as quasi civil servants into the mandarinate which administered the empire. Their churches were no longer obscure conventicles but public buildings of increasing magnificence. So much, and more, flowed from Constantine’s spiritual reorientation.

The church repaid Constantine’s generosity by presenting him as the model Christian emperor, the ‘friend of God’ who ‘frames his earthly government according to the pattern of the divine original’. The words are those of Eusebius, bishop of Caesarea, who lived from c. 260 to c. 340. Eusebius was a notable scholar and a prominent member of the little circle of court clerics who helped to school Constantine in Christian ways and to shape an image of him for contemporaries and for posterity. His Oration in Praise of Constantine, from which the passages quoted above are taken, is a prime example of fourth-century rhetoric, a work of oily panegyric which was hugely successful in carefully directing attention to all that was most admirable in its subject while discreetly drawing a veil over the less appealing features of the emperor’s character. It is not to Eusebius that we must go to learn that Constantine murdered his father-in-law, his wife and his son. On the contrary, Constantine was ‘our divinely favoured emperor’, who has received ‘as it were a transcript of the divine sovereignty’ to direct ‘in imitation of God himself, the administration of this world’s affairs’.2

Eusebius’ handling of Constantine requires to be considered in the context of early Christian thinking about the relationship between the church and the world. For simplicity’s sake one may distinguish two contrasting tendencies. The first was an attitude of wariness towards the secular world, of distrust, even of hatred for it. The Christian church was a society set apart, a ‘gathered’ community of the elect salvaged from the polluting grasp of the world, though still menaced by it in the form of the secular state, the Roman empire. The most violent expression of these views in early Christian writings is to be found in the book of Revelation, composed towards the end of the first century. The Roman empire is the beast, the harlot, ‘drunk with the blood of the saints and the martyrs of Jesus’. Keeping the world at arm’s length long remained an urgent concern among some Christian groups. We shall return shortly to some of its manifestations in the late antique period.

The second tendency was the quest for some form of accommodation with the secular world and the empire. This search was muted and hesitant at first but gained in confidence and assertiveness as time went on. The earliest sign of it may be glimpsed in the two New Testament books attributed to Luke. It is significant that both were dedicated to Theophilus, a patron of social or official eminence in that very world, secular, gentile and Romano-Hellenistic, which other Christians regarded with misgiving. A next step was to ponder the implications of the coincidence in time between the establishment of the Roman peace and the growth of the Christian church within the empire. Bishop Mellitus of Sardis, addressing an Apologia to the Emperor Marcus Aurelius about the year 170, could claim that the Christian faith was ‘a blessing of auspicious omen to your empire’ because ‘having sprung up among the nations under your rule during the great reign of your ancestor Augustus … from that time the power of the Romans has grown in greatness and splendour’. The next move was to suggest that the Roman empire was in some sense itself related to God’s scheme for the world. The first who dared to think such a thought was the great Alexandrian scholar Origen. In his work Contra Celsum, composed between 230 and 240 to refute the attacks on Christianity by the pagan philosopher Celsus, Origen had occasion to comment upon the following words in Psalm lxxii.7: ‘In his [the just king’s] days righteousness shall flourish, prosperity abound until the moon is no more.’ Origen observed that ‘God was preparing the nations for His teaching, that they might be under one Roman emperor, so that the unfriendly attitude of the nations to one another caused by the existence of a large number of kingdoms, might not make it more difficult for Jesus’ apostles to do what He commanded them when He said “Go and teach all nations” …’ Augustus therefore, who first ‘reduced to uniformity the many kingdoms on earth so that he had a single empire’, could be presented as the instrument of God’s providence.3

These accommodating tendencies were carried to extreme lengths after Constantine’s adhesion to Christianity early in the fourth century. Faced for the first time with an entirely novel situation, churchmen had to come to grips with the question, How is a Christian emperor to be fitted into the scheme of things? The most comprehensive answer was provided by Eusebius, explicitly in his Oration, implicitly in the work to which the Oration was a pendent, the Ecclesiastical History – the earliest work of its kind, the most important single source for our knowledge of the first three centuries of Christian history, and a potent literary influence upon the work of Bede. Eusebius brought the Roman empire within the divine providential scheme for the world. It was an astonishing feat of intellectual acrobatics, here summarized in the words of a modern scholar:

Eusebius sees the achievement of a unified Christian empire as the goal of all history. He insists on the mutual support of Christianity and Rome, of the monarchy of Christ and the monarchy of Augustus. For him, Roman empire and Christian church are not only essentially connected; they move towards identity … Eusebius can say that the city of earth has become the city of God, and that the monarchy of Constantine brings the kingdom of God to men.4

This Eusebian accommodation between church and empire became and long remained a cornerstone of the ‘political theology’ of the eastern empire and its successors. For the historian of conversion it has two significant implications. If empire and church are moving towards identity, if they are (in the words of another scholar) but ‘two facets of a single reality’, then one of the questions from which we started – Who is Christianity for? – acquires at once a sharper urgency and an answer. If Romanitas and Christianitas are co-terminous, then the faith is for all dwellers within the ring-fence of the empire but not for those outside. All dwellers within means the ‘internal outsiders’, the huge rural majority, whose evangelization will occupy us in the next chapter. Those outside means the barbarians.

Barbarians could be as effectively de-humanized by the educated minority as were the peasantry. ‘Roman and barbarian are as distinct one from the other as are four-footed beasts from humans,’ wrote the Spanish Christian poet Prudentius in about 390. His contemporary St Jerome was sure that some of the Germans were cannibals. ‘The holy priesthood, chastity and virginity do not exist among barbarian peoples; and if they were to do so, they would not be safe,’ wrote Bishop Optatus of Milevis in north Africa in the 360s. Ingrained habits of thought are revealed in the turn of a phrase. The Spanish historian Orosius, writing in about 417, could begin a sentence with the words ‘As a Christian and as a Roman …’ Quite so.5 The identities were conflated. In such a climate of opinion there could be no question of taking the faith to the heathen barbarian. In the words of a leading modern authority, ‘Throughout the whole period of the Roman empire not a single example is known of a man who was appointed bishop with the specific task of going beyond the frontier to a wholly pagan region in order to convert the barbarians living there.’6

One qualification needs to be made. If Christian communities came into existence outside the imperial frontiers they might request the church authorities within the empire to send them a bishop to minister to their needs. There was a variety of ways in which such communities might come into existence, by means of trading settlements, diplomatic contacts, veterans returning from service in the Roman army in the course of which they had been converted, cross-frontier marriage, the settlement of prisoners carried away from their homelands by barbarian raids, and so on. Here is an example. At the end of the fourth century Rufinus of Aquileia translated Eusebius’ Ecclesiastical History from Greek into Latin to render it accessible to the Latin-speaking west. He also brought it up to date, continuing it from where Eusebius had left off in Constantine’s day down to the death of the Emperor Theodosius I in 395. Rufinus had met the king of Georgia, in the southern Caucasus, who told him that his predecessor King Miriam, who reigned in the time of Constantine, had acquired a Christian slave-girl who had converted her master to Christianity. Rufinus did not know her name, though later sources were to name her as Nounè or Nino. Whatever may lie behind this story – perhaps a jumbled memory of diplomatic relations between Constantinople and Tiflis – we may be certain that Christian communities did exist in Georgia in Constantine’s reign, because reliable sources reveal that a certain Patrophilus, bishop of Pithyonta (Pitsunda), attended the ecclesiastical council of Nicaea in 325. The site of his bishopric on the Black Sea coast at the foot of the Caucasus suggests that maritime contacts with the Roman empire had given rise to the Christian community over which he presided. We shall examine some further instances of these extra-imperial communities in Chapter 3.

However, the Eusebian accommodation would not commend itself in all quarters. It would be looked upon with disfavour by those of the ‘gathered’ tradition. It was persons of this persuasion, largely if not exclusively, who were responsible for perhaps the most remarkable phenomenon of late-antique Christianity – the growth of monasticism. Withdrawal from the world by an individual to a life of ascetic renunciation and self-denial in a desert solitude had an obvious biblical precedent in John the Baptist. The gospel stories of the temptation of Jesus reinforced the notion that the desert, the wilderness, was the place where the truly committed might test their faith and overcome the wiles of the Devil. It was in the valley of the Nile, where the desert and the sown lie so close together, that Christian solitaries first made their appearance. The most famous of these early hermits was Antony, a Coptic peasant who ‘dropped out’ of his village community at the age of twenty, in about the year 270, and for the remainder of a very long life gave himself over to prayer and asceticism. His example was infectious. Though he retreated ever deeper into the desert he was pursued by disciples eager to follow his example and receive his spiritual guidance. It was to one of these followers, Pachomius – perhaps significantly, an ex-soldier – that there occurred in about 320 the idea that communities of ascetics might be organized, living a common life of strict discipline according to a written rule of life. Thus was monasticism born.

It spread like wildfire in the fourth century. In part this was perhaps because, in a church now at peace after the Constantinian revolution, ascetic monasticism offered a means of self-sacrifice which was the nearest thing to martyrdom in a world where martyrs were no longer being made. In part the call of the ascetic life could be interpreted as a movement of revulsion from what many saw as the increasing worldliness of the fourth-century church, the merging of its hierarchy with the ‘establishment’, its ever-accumulating wealth, the growing burden of administrative responsibilities which encroached upon spiritual ministry. Monasticism offered, or demanded, a manner of life in which individualism had to be shed. To be ‘of one heart and of one soul’ within a community, to have ‘all things common’, was not simply to follow the example of the apostles commended in Acts iv.32: it was also to be liberated from the insidious temptation of private cares, selfish anxieties. Such liberation offered the possibility to humans of building a heavenly society upon earth. The monastic vocation was a call to a new way of apprehending, even of merging into, the divine.

Its appeal was made the more seductive by some persuasive advocates. A Life of St Antony was composed by Athanasius, the great bishop of Alexandria, in 357. It is one of the classics of Christian hagiography. Its speedy translation from Greek into Latin made it accessible in the western provinces of the empire. By a happy chance there has survived a vivid account of the effect this work had upon a pair of rising civil servants in the early 380s.

Ponticianus continued to talk and we listened in silence. Eventually he told us of the time when he and three of his companions were at Trier. One afternoon, when the emperor was watching the games in the circus, they went out to stroll in the gardens near the city walls. They became separated into two groups, Ponticianus and one of the others remaining together while the other two went off by themselves. As they wandered on, the second pair came to a house which was occupied by some servants of God, men poor in spirit, to whom the kingdom of heaven belongs. In the house they found a book containing the life of Antony. One of them began to read it and was so fascinated and thrilled by the story that even before he had finished reading he conceived the idea of taking upon himself the same kind of life and abandoning his career in the world – both he and his friend were officials in the service of the state – in order to become a servant of God. All at once he was filled with the love of holiness. Angry with himself and full of remorse, he looked at his friend and said, ‘What do we hope to gain by all the efforts we make? What are we looking for? What is our purpose in serving the state? Can we hope for anything better at court than to be the emperor’s friends? … But if I wish, I can become the friend of God at this very moment.’ After saying this he turned back to the book, labouring under the pain of the new life that was taking birth in him. He read on, and in his heart a change was taking place. His mind was being divested of the world, as could presently be seen … He said to his friend, ‘I have torn myself free from all our ambitions and have decided to serve God. From this very moment, here and now, I shall start to serve him. If you will not follow my lead, do not stand in my way.’ The other answered that he would stand by his comrade, for such service was glorious and the reward was great …7

The author of this account, numbered among the audience of Ponticianus, was Augustine, later to become bishop of Hippo in north Africa. It occurs in his Confessions, the greatest work of spiritual autobiography ever written.

Augustine is important for us because out of his voluminous writings can be constructed a theology of mission which was to have far-reaching influence upon the concerns of the western church. In the first place, he was an African, and thereby the heir to a distinctive Christian tradition. The African church looked back to Tertullian (d. c. 225), lawyer and prolific Christian controversialist, and to Cyprian (d. 258), bishop of Carthage and martyr. The writings of these two fathers of the African church had expressed a rigorist view of Christianity, one which sought to keep the secular world at a distance. This intellectual tradition, widely respected in the western, Latin provinces of the empire, gave a twist to the character of western Christianity which differentiated it from the Christianity of the eastern, Greek provinces of the empire. Where the east, schooled by Origen and Eusebius, was assimilationist and welcomed the co-existence of the church and the world, the west tended to see discontinuities and chasms, and maintained a distrust for secular culture. If in the east church and state were nearly identical, in the west they were often at odds. Harmony was characteristic of the east, tension of the west. It was to be a critically important constituent of western culture that church and state should be perceived as distinct and indeed often competing institutions. Built into western Christian traditions there was a potential rarely encountered in the east for explosion, for radicalism, for non-conformity, for confrontation. To these traditions Augustine was the heir; to them he contributed in no small measure. His was a discordant voice in the general chorus orchestrated by Eusebius in celebration of the Christian empire. It would matter very much indeed that Augustine’s would prove to be among the most powerful and influential voices that western Christendom has ever heard.