Полная версия

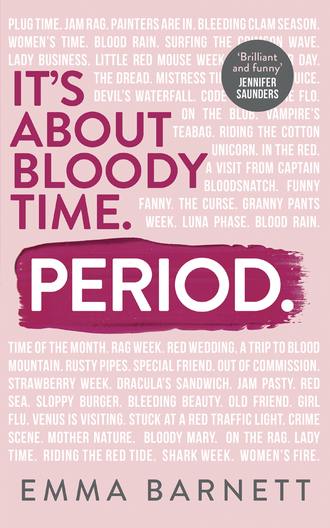

Period.

I remember him – and the subway has such distinct lighting – like I just remember him holding up these sheets, my menstrual sheets of shame, like menstrual sheets of doom. I realise that they didn’t look like menstrual sheets of doom, they looked like murder sheets of doom. He asked me to explain it, and I just start crying. And I can barely get the words out. I’m just trying to explain to him, it’s my period on those sheets. And I stole the sheets from the guy that I was with. And I know that that’s wrong.

Now, when I asked you if you would go to prison for your period, you might have laughed, but Jillian’s shame nearly led her down that road. Because, these two cops offered her an ultimatum: either go with them to the local police station, where they would file a report and ask her more questions, or take them (and the bedsheets) back to hot Jeffrey’s house to corroborate her story.

It is what Jillian confesses to This American Life next which I find so fascinating:

And I had to think about it … I honestly gave it a really solid, good think. There was a huge part of me that would rather go to the police station than have to go back and show Jeffrey these – not only show him these sheets, but also bring the police there. But, you know, my common sense caught up with me because this looks like I’ve done something very wrong.

Fortunately, Jeffrey, like the sexy period hero he is, when confronted by the cops, a nervous Jillian and the bloodied bedsheets on his doorstep, verified her story. Without skipping a beat, he simply explained that the sheets were covered with ‘menstrual fluid’. No shame. No juvenile euphemism.

Jillian, as you would expect, is by now a sobbing mess and in a line which could have come straight out of a Richard Curtis movie script, he calls her ‘wonderfully strange’.

Spoiler alert: if you’re interested in finding out whether their love affair worked out, it didn’t. Period night didn’t kill the relationship, it was actually American visa issues. But it’s not their love story that we’re focused on here, what I care about is that a woman – in one of the best first sex stories I’ve ever heard – was so ashamed of her period that she nearly chose a night in the police station over returning to the ‘scene of the crime’.

Take that in. It’s bonkers. Fully bonkers. But you know what’s even more crazy? Women the world over will understand why the police station inquisition was a serious option for a fully innocent Jillian because it seems we all have the propensity to become liars and weird little thieves when we get our periods. Anything to simply hide the evidence.

Take another woman I know, who also robbed some bedsheets. Jane was in her final year at school when she came on her period during a night out and didn’t have any tampons with her. She deployed ye olde faithful technique of stuffing one’s knickers with tissues and hoped for the best. Crashing at male mate’s family house for the evening, she woke up the following morning to her own crime scene spread across the bedsheets. Just because her friend was a guy, she felt she couldn’t talk to him about it. So, just like Jillian, she robbed the sheet, stuffed it into her handbag and then chucked it into a public bin on the way home. To this day, her mate’s mum still asks for her sheet back, and Jane is too embarrassed to tell her the truth.

Linen is never safe around a menstruating woman, but particularly, it seems, around a woman who is ashamed of her own blood.

We also become super sleuth laundry women. Another woman I know, now an accomplished doctor in America, had to steal and sneakily return a guy’s jeans so she could wash them:

My worst period story was probably in college, I had my period and needed to change my tampon but hadn’t yet – my then boyfriend came in to my dorm room and pulled me onto his lap … I’m sure you can see where this is going. I’m pretty sure I realised that I was sort of leaking through and then decided I just had to stay there forever. But eventually (obviously) I stood up and there was a real life Superbad moment AND I WANTED TO DIE. But actually, I just stole his jeans and immediately washed them, returned them and said nothing about it.

Truly horrifying.

You get the picture. Ludicrous behaviour abounds in women from all backgrounds and of all ages. All over some spilt blood.

And yet there is a serious level of irony that most young girls crave their first period, fretting about when they can join the ‘P-Club’ but spend the rest of their lives covering it up.

For one of my friends, this happened almost immediately. She’d just turned thirteen when her first period started, and her initial reaction was ‘BEHOLD ME, NOW I AM ALL WOMAN’. However, this was somewhat tempered by the fact that she was on a five-day school trip to the countryside and had to figure out how to climb down a rope frame without anyone realising she was bleeding (whilst simultaneously giving off the laid back, mature vibe of one who has just ‘become a woman’).

Crucially, I raise this mad urge towards concealment not because I think women should be talking about their periods all time, but because this culture can harm women’s health when they fail to seek diagnosis for menstrual conditions or gynaecological problems and furthers the stigma around periods – so it’s time to shine a glaring spotlight on this silence and our bloodied sheets.

Let’s take a step back for a minute and consider: what is the point of a period?

Other than the important business of reproducing, according to most doctors there is very little point. Galling, isn’t it?

Considering that this bleeding window in our lives is a relatively short amount of time – and only for those women who want or try to have babies – we are spending a heck of a lot of time and effort bleeding, when perhaps we don’t have to. (Not to mention the energy expended hiding this natural process from colleagues, friends and other halves.)

Dr Jane Dickson, the straight-talking vice president of the UK’s Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists’ Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare tells me:

A woman is built around her reproductive cycles. She is set up as a pregnancy machine … A period is a natural, in-built preparation system for pregnancy. But in this day and age there is no reason a woman should have periods if they don’t want them. It’s totally healthy to use contraceptives which stop bleeds altogether or create artificial periods.

Moreover, (and I hate to break it to you) artificial periods, the ones you have on many pills during the seven-day break, are also hangovers from an even more puritan age.

There is no reason for a one week break [within which to bleed] any more either. When the pill was first developed, it contained an extremely high dose of hormones – five times what the modern day pill contains now. It made many women feel sick and unwell. So, they liked the idea of a seven-day break from the heavy hormones.

But the pill was also developed in America – a heavily Catholic society – where contraception was frowned upon. If women could still have periods while on the pill, they could mask the fact they were using a contraceptive and it would be less stigmatising. And women themselves were reassured by seeing a period every month as healthy menstrual function.

As science has developed and the dosage is now greatly reduced – and contraception in many parts of the world is far less stigmatised – none of those reasons for a bleed exist any more. The pill just switches your ovaries off and keeps the womb lining suppressed. The injection dupes the body into thinking it’s pregnant; the Mirena coil suppresses the period – there is no point having a period whatsoever other than when you want to reproduce.

In fact, while writing this book, the official health guidance in the UK changed, finally revealing to women on the pill that they no longer needed to take the traditional break to have a bleed. I quote the guidance: ‘There is no health benefit from the seven-day hormone-free interval.’ And, ‘women can safely take fewer (or no) hormone-free intervals to avoid monthly bleeds, cramps and other symptoms.’

This is game-changing. And very overdue.

Pill-taking women across the world erupted in shocked and righteous anger at the news. For decades, women had been bleeding when they didn’t need to. It’s ludicrous. Why has it taken until 2019 for the official health advice to tell them their pill-periods were nonsense?

And the real red rag to the raging bull? Those fake bleeds were designed to make an old man in a white hat happy. Yup. It all comes back to the Pope. Professor John Guillebaud, a professor of reproductive health at University College London, told the Sunday Telegraph that gynaecologist John Rock suggested the break in the 1950s ‘because he hoped that the Pope would accept the pill and make it acceptable for Catholics to use’. Rock thought if it did imitate the natural cycle then the Pope would accept it.’

For more than six decades most women have unknowingly been taking the pill in a way that inconveniences them in order to keep the Pope happy. Digest that. Sticks in the throat a little eh?

Women felt and feel rightly duped. Another sodding period lie told for more than half a century to benefit someone other than the bleeding woman suffering unnecessarily.

Of course, some women don’t want hormones in their body. They like being natural. They want to bleed – regardless of ovarian intention. Some argue the time of the month is a source of strength for them, or perhaps they can’t find a pill or contraceptive which doesn’t make them feel ropey. Others argue that ovulating naturally is good for one’s health, as is the natural production of the progesterone and oestrogen.

I ventured to Dr Dickson that perhaps a period is useful as a marker of health or ill health – and she batted away my concern with that easy breeziness and reassuring aura of a fact-laden specialist. She explained to me that there are usually other symptoms to other illnesses which don’t require periods as a signifier. I.e., if you had cancer of the womb, you would bleed anyway even if you were on a pill that stopped you bleeding; or polycystic ovaries would manifest through a range of other factors, such as excess hair growth or loss due to overactive male hormones.

It’s at this point I have something to confess to you.

While penning a book about periods I haven’t had a single one. Not so much as a menstrual splash until the very last chapter (you’re in for a treat). It feels odd, dishonest somehow, though I’ve definitely done my time in the menstrual trenches. I have indeed bled while writing. I did that for about six weeks. But it wasn’t menstrual. My period hiatus is because I’ve been pregnant. Pregnant with a baby I could have so easily missed out on having. And now, despite all of my doom-infused expectations I’ve had said baby (whoop!) – hence the six-week post-birth bleed. And then, because I’ve been breastfeeding the beauteous wonder that is our son, while battling mastitis (the vile blocked duct breastfeeding infection), I have yet to bleed naturally.

I have already told you it took two decades for me to be diagnosed with endometriosis, a debilitating period disorder that affects one in ten women – including Marilyn Monroe, Hilary Mantel and Lena Dunham, if you want to know the A-List.

I have already told you of my bewilderment and shame that I, a vociferous woman who loves asking tough questions and soliciting the truest answers I can, had failed again and again to secure a diagnosis – despite having traipsed in and out of doctors and gynaecologists over the years complaining of severe pain.

But what I haven’t told you is how my lack of diagnosis could have cost me and my husband the chance to have a biological baby.

And my experience strikes at the heart of why I am urging women to drop the shame a male-organised society has foisted upon us: our wellbeing and health.

But make no mistake, I am not preaching about the need to drop the period stigma so women are more clued up about their fertility. (Although this is a desirable side effect should women care to have children.) This is not some kind of dystopian Handmaid’s Tale plot twist.

Instead, I want to share what happened to me as a way of highlighting how knowledge is power. And how important it is to be as unashamed as possible, so we keep pushing for answers about areas of women’s health which have for centuries existed in the shadows. Too many women are simply soldiering on while struggling with all sorts of gynaecological and sexual issues because they think that is their lot in life.

Bluntly put, often we put up with our internal lady piping and vaginas not quite working as they should because we are embarrassed and we don’t believe it to be our absolute right for everything to be more than all right.

Nor are we always believed by the doctors who listen to our woes – once we muster up the energy to try to communicate our problems.

I always knew something was wrong with me gynaecologically but I too soldiered on. From age eleven, these heavy painful periods were the norm. I tried everything – strong painkillers, drinking coffee (which I loathed but my mum had heard could help), furry hot water bottles, lying on my stomach, and then, as I grew older, getting just that little bit more drunk on nights out when I was either about to start or in full flow. And then at university, I finally found a pill which agreed with me (although not the large quantities of booze I was imbibing – I went from being an excellent loving drunk to quite the vile bitch drama queen). Hence began the great cover-up as I like to call it.

From the age of twenty-one to thirty, I happily chomped my way through pill packet after pill packet, and my periods, although still uncomfortable, became more manageable. But when my husband and I decided perhaps we should start thinking about having a baby and I ditched the pill, my real periods – the dark bastards – really started to return.

We couldn’t get pregnant. We seemed to have gone from a place of not wanting a baby urgently, to everyone around me falling pregnant. Suddenly I was in a place I’d always feared: infertility. Because somewhere deep down, I knew I wasn’t quite right, even though every doctor and specialist told me I merely had a bad case of dysmenorrhoea, a fancy word for painful periods. With a great sense of foreboding, I had secretly dreaded the stage of my life when I would attempt to produce life, convinced something might be wrong. And here I was. And it wasn’t going well. Far from it.

As each month went by during our two years of trying, my periods were getting worse. They were starting to reveal themselves in their full natural horror, free of the contraceptive mask which had been restraining them for the last decade. The lowest point I can remember on this knackering journey was during a holiday in Sweden, from whence my mother-in-law hails, walking behind her, my father-in-law and my husband, after a sunny coffee and cinnamon bun pit stop on a picnic bench. I felt like iron chains were dragging my stomach down, pulling me towards the floor, as my bones ground against each other during what should have been a lovely easy amble around a Stockholm park. I came to a complete stop, unable to take another step. I just couldn’t move anymore. The period pain was so great. I stumbled to the closest bench and didn’t move for a long, long time.

That was the moment I knew I needed some cold hard medicine. Not some muddy herbal tea nonsense from an overpriced acupuncturist. Nor another expensive and pointless colonic irrigation that did nothing other than to make me feel lightheaded and immediately crave a greasy cheese and caramelised onion toastie.

On that day, I admitted the first of two defeats. The first was that something was wrong with me to the extent that action was required. A week later I was booked in for a laparoscopy, a keyhole procedure which serves both as a diagnostic tool and a treatment for endometriosis. So, you sign off having a diagnosis and treatment while you are under anaesthetic, meaning you either wake up after a few minutes as no action was required or after a few hours as the doctor has been beavering away.

I was the latter. I did indeed have it, endometrium (old womb lining which should leave one’s body during a period), coating my organs, mainly my bowel and bladder, but very luckily it hadn’t stuck to my ovaries, uterus or fallopian tubes. The disease was at stage two of four. Moreover, after two and half hours of painful lasering (during which they inflate your organs with air) the doctor felt he had managed to remove all of it.

In the six months after a laparoscopy, women who have struggled to conceive naturally because of endo have a much higher chance of doing so. And the debilitating pain can go away or be significantly reduced. Sadly, despite our best efforts – and they really were Herculean – pregnancy still wasn’t happening and my periods were as punishing as ever.

Hence came my second defeat, as I stupidly and naively chose to view it at the time: I agreed to IVF. Not being able to fall pregnant felt like a huge failure. We’d been told repeatedly that our infertility was unexplained, so I had strongly resisted the idea of IVF previously because having such a major intervention felt like I really had failed and that we’d reached the end of the road.

An amazing older female doctor in the NHS promptly disabused me of this foolish opinion. She met with me and my husband for an appointment regarding our ongoing issues and my recovery following the removal of my endometriosis. All I really remember about this meeting with this wise, stern but kind doc, was her shiny grey ponytail and her saying something along the lines of: ‘For God’s sake Emma, stop being so stubborn and just have IVF. You’ve qualified for it on the NHS for a long time now, especially because you have endometriosis and have tried for more than two years to get pregnant. What have you got to lose? Your periods are awful each month and this is one way of trying to stop them and get pregnant before. It’s really a win-win situation.’

Before I knew it, despite all of my reservations about the hormones, the intervention, the hope, the potential crushing disappointment and the overarching feeling of total failure, I found myself saying yes.

The doctor sold the process to me on potentially ending my periods for a little while (that’s how bad they were) and I consented to the hormonal rollercoaster that is IVF without a millisecond of further contemplation. I didn’t for one moment dare to think it might work and produce a baby. No, that would be far too easy and require a dose of luck I didn’t seem to possess with my wrecked body.

I remember my husband saying: ‘Emma, wait. Shouldn’t we discuss this?’ As we were both bundled off for various blood samples, clutching consent papers. I turned back to him and simply replied: ‘No. I can’t go on like this.’ He went with it unquestioningly, because he’s a legend.

We had a big holiday already in the diary: three weeks travelling around China (another ‘we can’t get pregnant’ adventure holiday – where you splurge money on an amazing voyage in a bid to distract yourselves from the pain of unexplained infertility). Hero doctor agreed to wait until we came home. By this point, I was totally in her hands and meekly agreed to everything she said. It just felt so good to have someone else take control and bring some order to my menstrual and mental chaos, caused by not being able to conceive and not being able to exist easily in my pain-wracked body for one week every month.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.