Полная версия

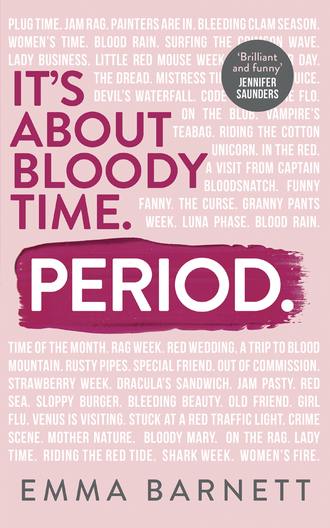

Period.

It is clear that religions haven’t been solely responsible for all period myths – doctors, tribe chiefs and the great thinkers of the day have all contributed their own bits of gibberish. However, all of the major faiths do still have a lot to answer for, as I found out to my surprise the year I got married.

I was born into a Jewish family, and brought up culturally Jewish – so, big Friday night dinners, a decent level of Jewish education until the age of twelve at Sunday school and attending my fair share of Bar Mitzvahs. And despite not being particularly religious or observant, the ideal romantic situation envisaged by my family was that I would eventually find a Jewish guy.

I always explain to people who struggle to understand why you might prefer to marry Jewish if you are Jewish but aren’t that religious, that it’s akin to wanting to marry someone from a similar background to you. That’s all. Someone who immediately gets your weird home rituals without explanation, understands your family’s quirks and with whom you have a shared history. But I should stress I probably would have also married outside of my faith too – because I believe in falling in love which is nigh on impossible to prescribe.

On a practical level, it’s really tough to find a Jewish mate, especially in the UK where there are now fewer than 250,000 of us in total, and the only part of the community which is growing in number is the ultra-orthodox. So, finding a Jew who is similar to you in terms of religiousness and outlook (as well as the million other ingredients that go into being compatible with someone) is tricky, especially as you’re shopping in a very small store. But, somehow, I did indeed land my match and amazingly, he happened to be Jewish. A lucky bonus for me.

When I met my husband, aged 20, I was wearing a blue Nottingham uni theatre T-shirt with my name emblazoned across the back (sexy, I know), because I’d recently been elected president and, before the journalism bug hit, I harboured dreams of acting and he was wearing stripy Birkenstocks. Also très sexy. I was in a flap and attempting to deal with a severe budget cut to the theatre’s meagre pot. Except my grasp of general maths, spreadsheets and deficits weren’t the greatest.

My fun-loving mate, Gemma, from my politics class I occasionally attended, had told me that her friend could help – plus, he was single, good at maths and HOT. Boldly, I introduced myself to him, and after some sexy budget chat in front of the theatre’s noticeboard I found myself complimenting his Birkenstocks and asking for his number, sober, in the cold light of day.

Long after that first encounter, he told me how bowled over he was by this forward northern woman demanding his digits. Fast forward through many dates, holidays, jobs and postal addresses, we are about to celebrate fourteen years together. And, even though it was daunting having met each other so young, at the peak of sowing our wild oats, we have stood the test of the time (even if the Birkenstocks haven’t). But why am I telling you how I met my husband? Because seven years on from that first meeting in front of the noticeboard, we were back there and something he did inadvertently led to us getting up close and personal with my period.

I’d been invited back to Nottingham University to give a lecture to politics students about how to get into the media. My other half had merrily tagged along. It was our first weekend back in the city since we graduated, and a little tipsy on red wine after a cosy dinner, I unwittingly set up my own wedding proposal. ‘Wouldn’t it be fun to stand in front of the noticeboard on the exact spot where we met?’ I asked, excitedly half running to the very point, with him smiling and walking behind me. Five minutes later, my then boyfriend was down on one knee asking me to marry him.

We decided to get married at a synagogue we’d recently discovered in London’s Bayswater, while renting locally. We had passed this beautiful building countless times, but being rather rubbish Jews had wrongly assumed it was a church. Finally, having made it inside on a random Saturday and been proven wrong, we fell in love with this Moorish-style temple and were charmed by the friendly local community and the brilliant rabbi, who was modern and amenable to our needs and religious crapness (my words, not his).

Someone in the community mentioned there were people who would happily give us the low down on Jewish marriage if we wanted to hear more about the experience. Always a sucker for learning and the chance to ask questions, I signed us up.

Now, if you were offered the chance to hear more about your faith and marriage ahead of your pending nuptials – what would you expect to learn? Perhaps some wisdom about love, sex, the wedding ceremony, family and being a single unit. I was hoping for tales of love in the Bible and to find out any kosher kissing tips (I jest. Slightly). My fiancé was just hoping to survive the experience. What percentage of that conversation would you expect to be about periods – a topic you’d never even really discussed at length or in any serious detail with your husband? 2 per cent, if that?

Well, 75 per cent of our informal session was about periods. My period to be precise. And how ‘impure’ it made me for nearly half of every month.

And that’s how my husband’s romantic university proposal ended up leading to one of the most memorable conversations I’ve had about my menstrual flow.

We barely had a chance to sit down upon meeting our informal guides, before the foreign concept of niddah was brought up.

Before my fiancé and I could exchange quizzical looks, I was invited to speak privately with the female volunteer. Finally, I thought, this was more like it. It was time for the good stuff in my girls-only chat.

Settling into a comfy sofa, the friendly woman began what has now become known in my friendship circle as ‘the legendary period talk’. Smiling at me, she said something along the lines of: ‘Emma, when you bleed each month, you become niddah. Impure. Unclean for your husband. And this lasts until the very last drop of blood has come out of you and you have cleansed your whole self in the mikveh pool. Do you understand?’

She then told me that, during this two-week window of time,

I was wasn’t even allowed to touch my husband’s sleeve, or, in my favourite example, pass him a piece of steak I’d cooked for his dinner.

As I was still digesting her words and mulling over how he was better at cooking steak than me, she began confiding the romantic and practical benefits of niddah. She told me that, like with anything in life, restraint makes something sweeter when you have it again after a while. Not touching for nearly two weeks every month meant you couldn’t wait to touch each other again, after the mikveh. And, handily, this would also be the right time in your cycle to get pregnant. Who’da thunk it? Plus, she confided, it’s sometimes nice to have a break from sex and your husband for half a month, every month.

My softly-spoken guide sat back, pleased with her explanation of how the Orthodox Jewish way had thought of everything. And while a small part of it seemed plausible (i.e. the part about abstinence making the sexual pull stronger), I felt as if I’d fallen down Alice’s rabbit hole and was struggling to re-emerge from Wonderland.

But the truly jaw-dropping revelation was yet to come. Before entering the mikveh pool – a pool which, I should add, you cannot enter with nail varnish on or even your hair plaited (a place my mother had religiously avoided her whole life) – I had to be completely sure that my period had finished. So how can you be 100 per cent sure, beyond your own eyes telling you that your tampon is clear and your pants are pristine?

A kosher rag.

Yes, you read that right. There is a special cloth you can buy to wipe yourself with so that you can double and triple check that your period has properly ended. But oh, no, no – that’s not all you can do to ensure your purity …

If at the end of your cycle, after you’ve wiped yourself with said specially blessed rag, you are still in doubt, you can post the scrap to your local rabbi in an envelope with your mobile number enclosed. After he’s inspected it, you will simply receive a text telling you whether you are kosher or not for swim time at the mikveh. According to my smiling guide, they are ‘specially trained’.

Yes, Jewish women are wiping themselves with and then posting bits of cloth to a bearded man down the road.

My own brazenness started to falter here, and I didn’t press any further. I have often wondered since about the identity of the first dude who figured he had the expertise to pass on this knowledge to all the other men who have never menstruated in their lives. I can’t recall much more from that session other than the moment my fiancé suddenly reappeared from his part of the house and swept me out of there. We both felt a bit sick – him from too many salty and sweet snacks, and me from a very odd period chat.

‘They do WHAT?’ was his general reaction, as I explained about the rabbi rag watch.

Meanwhile, in the other room, my fiancé had been given a more pared down version of how periods affect women, with a similar emphasis on ‘no touching’ during my ‘impure’ period. But I’ll never forget what else he had been told: ‘Women are a little crazy when they are on their periods’ – with the implication that, in fact, it was good for all husbands to have a break from their wives at this point in our monthly cycle. Yes, really.

(Later, in a totally unrelated conversation with a friend, I also discovered that women who are trying to fall pregnant can post vials of their period blood to clinics in Greece, who claim they can analyse the sample to spot potential fertility problems. It makes you wonder what other bizarre packages are being sent through the post, doesn’t it? Again, another rabbit hole.)

I must stress this: the people we met were kind and only trying to educate us in the ways of ultra-Orthodox Judaism. I don’t wish to be uncharitable towards them; my criticisms aren’t personal. And, of course, other folk could have sold this purity period-obsessed side of marriage to us in a softer way. Or not focused on it as much. But I am grateful for receiving an unvarnished insight into what one of the oldest religions in the world teaches couples about women, our bodies and purpose on this earth.

I know that some modern Orthodox Jewish women have reclaimed the mikveh as an empowering space for them to feel cleansed and almost reborn each month – but why is period purity even still a thing in the first place? A step forward in the dark isn’t a step forward to me. Teaching girls and women that they are dirty and in need of rebirth after something as perfectly natural as a period isn’t right, however it is spun.

Nor am I looking to solely point the figure at Judaism. God knows (and he really does), it’s a religion with enough haters already. Judaism is certainly not unique when it comes to the major world faiths pillorying or discriminating against women for menstruating. Far from it.

Factions of Islam believe women shouldn’t touch the Qur’an, pray or have sexual intercourse with their husbands while menstruating. Muslim women are similarly deemed impure and must be limited in terms of contaminating their faith or their men.

Catholics fare no better, but seem to prefer to whitewash the whole affair. According to Elissa Stein and Susan Kim’s book, Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation, when Pope Benedict visited Poland in 2006, TV bosses banned tampon adverts from the airwaves for the duration of his stay – in case his papal Excellency was grossed out.

Certain Buddhists still have placards outside temples that bleeding women shouldn’t enter. I recently saw such a sign outside a stunning temple in the heart of modern buzzing Hong Kong, of all places.

In Uganda, particular tribes still ban menstruating women from drinking cows’ milk because they could contaminate the entire herd. And in Nepal, right now, menstruating women and girls are relegated to thatched sheds outside the home and are prevented from visiting others, in a charming practice known as ‘Chapadi’, because it’s believed that a bleeding woman in contact with people or animals will cause illness and is just wrong.

Most Hindu temples also ban women from entering when they are bleeding. Some go further by banning women of menstruating age altogether. A particularly eye-opening case made headlines in India in 2018, when activists were successful in getting the country’s Supreme Court to overrule such a ban at one of Hinduism’s holiest temples. Historically, the Sabarimala temple has not allowed women between the ages of ten and fifty to attend because they could be menstruating and therefore will be unclean. Violent protests broke out at the temple after the ban was lifted, with many extremely angry men accusing the courts and politicians of trying to ‘destroy their culture and religion’ by allowing menstruating women access to what should be a peaceful place of prayer. Crowds tried to block any plucky female worshippers, female journalists were attacked and one of the women who tried to attend the temple ended up needing a police escort.

The saddest part of the whole unnecessary debacle? The number of women who attended the protest in support of their own ban. That’s how deep these myths can run. Women can be so convinced by men of their own filth that they turn on other women.

Devastatingly, Hindu girls and women also miss out on mourning their loved ones while menstruating because of this type of temple ban. Instead, they have to stay at home while the rest of the family pay their respects. Or, in the case of BBC journalist Megha Mohan, loiter outside the temple in Rameswaram (an island off the south Indian state of Tamil Nadu) as her family observed the final ritual for her grandmother.

While waiting, she recalls in a piece for the BBC News website, texting a female cousin, who couldn’t make it to the final ritual, to tell her about her aunt stopping her from going to temple as she had asked for a sanitary towel:

She sympathised with me and then she paused, typing for a few moments. ‘You shouldn’t have told them you were on your period,’ she wrote, finally. ‘They wouldn’t have known.’

‘Have you been to the temple on your period?’ I asked.

‘Most women our age have,’ she said casually and, contradicting my aunt’s earlier statement just half an hour earlier. She added, ‘It’s not that big a deal if no one knows.’

So, she could have just lied. And probably should have done to get her way.

Looking back further, Roman philosopher Pliny the Elder wrote in AD 60 that having sex with a woman on her period during a solar eclipse could prove deadly.

Sure, mate. But this example shows just how long we have lived with this ritualised shaming of women.

Jump forward two millennia, back to London and my wedding lessons – it was so very odd to hear such backward advice still underpinning the way women are made to feel today. In the developed world, religion may not have the control it once had, but it’s still a huge cultural force that shapes norms and makes people feel a certain way about things.

Often, as with so many other day-to-day battles that make us weary, we can zone out when a religious teacher says something we would normally question. But keeping this shaming, impure narrative around periods going within our oldest religious institutions, despite leaps in medical advancements, at the very least has the subliminal effect of making women feel dirty and wrong.

And it reinforces the idea amongst men that our periods are something to fear and be sickened by.

So, question the nonsense when you happen to hear it. By all means laugh at it. Make sure you ridicule anyone who tells you that you are impure for your body doing something so natural that the entire human race depends on it. It isn’t easy. I failed to do so out of a mixture of shock and a fear of offending the kind people trying to prepare me for my wedding. And I still regret it.

You are a warrior – who bleeds and goes to work every day. Not some dirty hermit who deserves to be quarantined and needs male approval to be reintegrated into mainstream society after your monthly bleed.

Religion has no borders. It was viral before the internet. That is why a privileged educated woman like myself can be told, while living in one of the most advanced societies on earth, not to hand my husband a piece a steak I’ve made for him while menstruating. I am about as far away as you could get from a girl in Nepal banished to menstrual huts away from her home while she bleeds. And yet, we ended up getting a similar memo. Except I have the tools, power and voice to push back.

You see, without us realising it, these myths permeate, settle and erode confidences. Keep your antennae up and tuned. And have the confidence to belly laugh and challenge the shaming beliefs in religion.

Our periods hold the key to bringing the next generation of society into being. The least we can do is make sure we have the right attitudes towards them and diagnose any lingering bullshit from the days when only men had the power to tell the stories that narrated and controlled our destinies, regardless of whether they understood us or not.

Today, women control our bodies and our narrative.

We must not lose control of that hard-won right – especially over our periods – at a time when our voices are louder than ever before.

You can choose your reaction. That’s a power which must not be forgotten. Don’t internalise any of the shame these myths propagate. And remember to actively call out nonsense when you hear it.

CHAPTER THREE

‘What if I forget to flush the toilet and there’s a tampon in there? And not like a cute, oh, it’s a tampon, it’s the last day. I’m talking like a crime scene tampon. Like Red Wedding, Game of Thrones, like a Quentin Tarantino Django, like, a real motherfucker of a tampon.’

Amy Schumer, Trainwreck

It’s time to focus on the group of people who are nearly as good as the men at period shaming.

Women.

It definitely isn’t our fault the way society is set up to be only horrified or titillated by women’s bodies. Nor is it our fault that we are the ones tasked with physically producing the next generation (the very reason for periods in the first place) – a role which tests our bodies and minds in all sorts of unacknowledged and undervalued ways.

But when you live and breathe in the bubble which normalises such attitudes, you internalise them and make them your own. Which means women end up feeling ashamed of a perfectly natural bodily process, often ignoring their bodies’ cries for help and, in turn, shaming other women too.

Remember the confession booth we built for my radio show? I’ll never forget the softly spoken woman in her twenties who poured this truth into my ear:

‘Periods suck. We women are complicit in the silence.’

She isn’t wrong. We are complicit. And such desire to stay silent about our monthly bleeds leads to all sorts of ludicrous scenarios and some very serious ones too, which I will come onto with my own near-miss situation.

But let’s start with an absurd tale, one which perfectly sums up how women can be their own worst enemies when it comes to making periods taboo.

I only inquire because one woman nearly did time in the can, simply because she couldn’t bear to confess she was menstruating.

Let me tell you about the Canadian performer, Jillian Welsh. She poured her heart out to producer Diane Wu on the hugely popular podcast This American Life about a bloody evening scorched onto her brain and has kindly given me permission to reproduce her story in this book, aptly signing off her note to me ‘yours in blood’ (I love her already). The episode was focused on romance and how rom com scripts would play out in real life. Or not, as the case may be.

Jillian was twenty and studying theatre in New York when she met and fell for Jeffrey, whom she was starring alongside in a Shakespeare production. Fast forward to the wrap party and the cast night out. One thing led to another, they kissed and ended up back at his place. So far, so good.

Except Jillian’s Aunt Flo was in town. Due to her highly conservative background she couldn’t bring herself to even say the word period, let alone tell her new beau that she couldn’t do the dirty because she was menstruating. But, finally, she fessed up – and guess what? He didn’t care. Excellent sexy time ensued, after which Jeffrey went for his postcoital wee and shower, flicking the light on as he exited bedroom stage left.

As Jillian recounted to This American Life:

It looks like a crime scene. There is blood everywhere. This is the first time I had seen so much of my own menstrual fluid. I was afraid of it. I couldn’t even fathom what he was going to think about it … And then I don’t know how this happened, but my very own red, bloody hand print is on his white wall … He didn’t have any water or anything in his room, so I used my own saliva to wipe the bloody hand print off of the wall, like, out, out, damn spot.

OK let’s pause there. It’s grim but not that grim. However, it gets worse. Deliciously so.

Jillian then decided the best strategy to deal with Jeffrey’s desecrated bedsheets was to stuff them into her rucksack, because she couldn’t bear the idea of him having to wash them. She then covered his bed with his throw and prepared to scarper as soon as he was back from his shower. She offered a lame excuse, he looked suitably hurt and off she trotted to the subway, upset and laden with stained, stolen sheets.

Then it really hits me that I have stolen this man’s sheets. How do you come back from that? How do you – how are you not the weird girl who took his bedsheets? … So then I’m so inside myself and I hear this voice being like, ‘Ma’am, excuse me, ma’am.’ And I look up. And in New York, they have this station outside of subway entrances with this folding table and the NYPD stands behind. And it’s a random bag search.

Let’s pause again. What would you do? I know for certain I’d brick myself as soon as I was aware I looked like a murderer on the underground.

Jillian also panicked and pretended not to hear the officers, playing that, ‘I am invisible game’ you enact as a kid when there is nowhere left to run and you just hope by praying hard enough no one can see you anymore. She left the subway with a quickening pace. But to no avail. The officer soon caught up with an increasingly suspicious looking Jillian, opened her rucksack and saw the fruits of her sexual labour: crusty blood-soaked sheets.