Полная версия

Sea People

It was said, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, that the inhabitants of the Tuamotus were the finest canoe builders in the eastern Pacific, and that when chiefs on the high island of Tahiti wanted to build a great canoe, “they had need of the help of men from the low islands.” One eighteenth-century British commander described a double-hulled canoe that he saw in the Tuamotus as having hulls that were thirty feet long. The planks, which were sewn together, he wrote, were “exceedingly well wrought,” and over every seam was a strip of tortoiseshell, “very artificially fastened, to keep out the weather.” All Polynesians gave proper names to different parts of their canoes, including the thwarts, paddles, bailers, anchors, and steering oars. But in the Tuamotus it is said that even the individual boards were sometimes named, the old timbers serving as “reminders of the courage, endurance, and success” of those who had preceded them upon the sea.

Europeans greatly admired the craftsmanship of these vessels, but they also felt there was something a little startling about the idea of people putting to sea in boats that had been stitched together from scraps of wood. One early-eighteenth-century explorer recalled seeing a man some three miles out to sea in a craft so narrow it could accommodate only one person, sitting with his knees together. It was made, like the Nukutavake canoe, of “many small pieces of wood and held together by some plant,” and was so light it could be carried by a single man. Watching the progress of this canoe on the ocean was something of a revelation. “It was for us wonderful,” he wrote, “to see that one man alone dared to proceed in so frail a craft so far to sea, having nothing to help him but a paddle.” It was the merest inkling that here was a people with a different relationship to the ocean—people who could make their home on an atoll, people who could sail out to sea in a stitched ship—but, having little time or inclination to ponder the matter, the recorder of this interesting little tidbit turned and sailed on.

Outer Limits

New Zealand and Easter Island

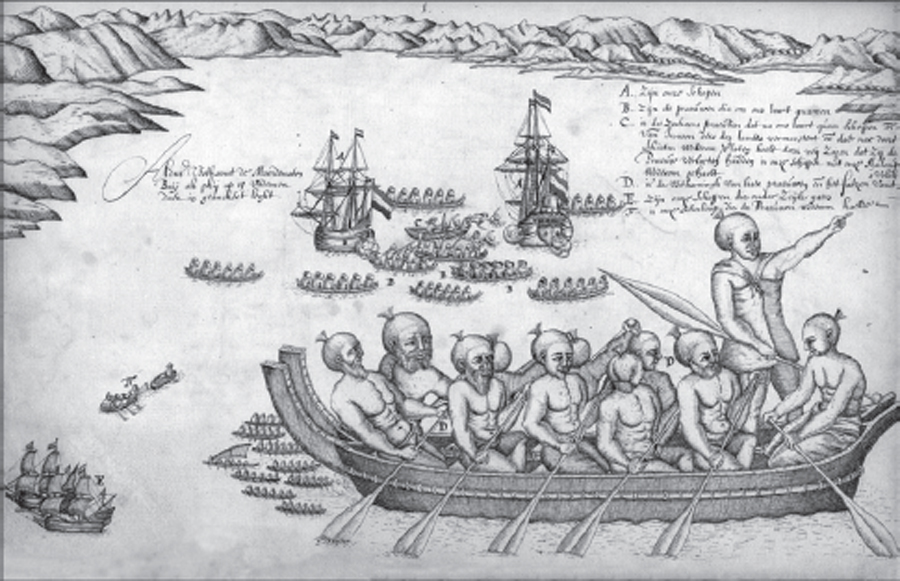

Murderers’ Bay, New Zealand, 1642, from Abel Janszoon Tasman’s Journal (Amsterdam, 1898).

DEPARTMENT OF RARE BOOKS AND SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, PRINCETON UNIVERSITY LIBRARY.

ALL THE ISLANDS in the mid-Pacific are either high or low, volcanic or coralline. But down in the southwest corner, near the ocean’s edge, there is a large and important group of islands with an entirely different geologic history. New Zealand is one of the anchoring points of the Polynesian Triangle and a key piece of the Polynesian puzzle, but it differs from other Polynesian islands in several ways. It lies much farther south, in latitudes comparable to the stretch of North America that extends from North Carolina to Maine. It is temperate, not tropical; it can be hot in summer, but in the winter, at least in the south, it snows. New Zealand is also vast by comparison, with plains, lakes, rivers, fjords, mountain ranges, and a land area more than eight times that of all the other islands of Polynesia combined.

The islands of New Zealand are also unique in Polynesia in that they are, geologically speaking, “continental.” New Zealand is part of the ancient southern supercontinent of Gondwana, which once included all the Southern Hemispheric landmasses of Africa, South America, Antarctica, and Australia, as well as the Indian subcontinent. About a hundred million years ago, this supercontinent began to break up, and a piece of it drifted off into what is now the Pacific Ocean. Most of this fragment was submerged beneath the sea, but near the junction of the Australian and Pacific Plates, some of it was thrust up by tectonic forces. The result was the landmass we now know as New Zealand, or, to use its modern Polynesian name, Aotearoa. New Zealand still sits on this tectonic boundary, which is why it has earthquakes and active volcanoes.

Because it was part of old Gondwana and because it is insular and was isolated for tens of millions of years, New Zealand has a quirky evolutionary history. There seems to have been no mammalian stock from which to evolve on the Gondwanan fragment, and so, until the arrival of humans, there were no terrestrial mammals, nor were there any of the curious marsupials of nearby Australia—no wombats or koalas or kangaroos, no rodents or ruminants, no wild cats or dogs. The only mammals that could reach New Zealand were those that could swim (like seals) or fly (like bats), and even then there are questions about how the bats got there. Two of New Zealand’s three bat species are apparently descended from a South American bat, which, it is imagined, must have been blown across the Pacific in a giant prehistoric storm.

Among New Zealand’s indigenous plants and animals are a number of curious relics, including a truly enormous conifer and a lizard-like creature that is the world’s only surviving representative of an order so ancient it predates many dinosaurs. But the really odd thing about New Zealand is what happened to the birds. In the absence of predators and competitors, birds evolved to fill all the major ecological niches, becoming the “ecological equivalent of giraffes, kangaroos, sheep, striped possums, long-beaked echidnas and tigers.” Many of these birds were flightless, and some were huge. The largest species of moa—a now extinct flightless giant related to the ostrich, the emu, and the rhea—stood nearly twelve feet tall and weighed more than five hundred pounds. The moa was an herbivore, but there were also predators among these prehistoric birds, including a giant eagle with claws like a panther’s. There were grass-eating parrots and flightless ducks and birds that grazed like sheep in alpine meadows, as well as a little wren-like bird that scampered about the underbrush like a mouse.

None of these creatures were seen by the first Europeans to reach New Zealand, for two very simple reasons. The first is that many of them were already extinct. Although known to have survived long enough to coexist with humans, all twelve species of moa, the Haast’s eagle, two species of adzebills, and many others had vanished by the mid-seventeenth century, when Europeans arrived. The second is that, even if there had still been moas lumbering about the woods, the European discoverers of New Zealand would have missed them because they never actually set foot on shore.

AS WITH THE other islands of Polynesia, the European discovery of New Zealand was essentially a function of geography and winds. The vast majority of early European explorers entered the Pacific from the South American side. But there was another way in, from the west, and in 1642 a captain in the service of the Dutch East India Company sailed this route for the first time.

The Dutch East India Company, which was headquartered in Batavia (now the Indonesian capital of Jakarta), was the great mercantile engine of the seventeenth century, and all the major geographic discoveries in the Pacific during this period were made by Dutch captains in search of new markets and new goods for trade. One of these was a commander named Abel Janszoon Tasman, who, in 1642, set out with a pair of ships bound for the southern Pacific Ocean. Tasman followed what looks, on the face of it, like the most unlikely route imaginable. Departing from the island of Java, he sailed west across the Indian Ocean to Mauritius, a small island off the coast of Madagascar, which itself is a large island off the coast of southeastern Africa. There, he turned south and continued until he reached the band of powerful westerlies that would sweep him back eastward, all the way across the Indian Ocean, until he finally reached the Pacific. Tasman followed this lengthy and unintuitive route—sailing nearly ten thousand miles to reach an ocean that was less than twenty-five hundred miles from where he had begun—because the winds and currents in the Indian Ocean operate the same way they do in the Pacific, circling counterclockwise in a similar gyre.

The main obstacle between the Indian and Pacific Oceans is the continent of Australia, and the earliest Dutch discoveries in the seventeenth century were off Australia’s west coast. But Tasman’s route took him so far south that he missed the Australian mainland altogether, and the first body of land he met with after leaving Mauritius was the island, later named in his honor, of Tasmania. Continuing on to the east, he crossed what is now the Tasman Sea, and about a week later he sighted a “groot hooch verheven landt”—“a large land, uplifted high.” It can be difficult to tell how large a body of land is from the sea—European explorers were constantly mistaking islands for continents—but this time it was unmistakable. The land before them was dark and rugged, with ranks of serried mountains receding deep into an interior overhung with clouds. A heavy sea beat upon the rocky coast, “rolling towards it in huge billows and swells,” offering no obvious place to go ashore. So Tasman turned and followed the land as it stretched away to the northeast.

For four days they sailed with the wind from the west, keeping their distance for fear of being driven onto the rocks. From the sea, the country looked dark and desolate. But at last, on the fourth day, they came to a long, curving spit bending round to the east, enclosing a large bay. Here they saw smoke rising in several places—a sure sign that the country was inhabited. Tasman and his officers decided that they would go ashore, and by sunset on the following day they had brought the ships to anchor in the bay. From there they could see fires burning on shore and several canoes, two of which came out to meet them in the gloom. When they had come within hailing distance, the islanders called out in “a rough loud voice,” but the Dutch could not understand them. They had been equipped at Batavia with a vocabulary, almost surely the word list assembled twenty-five years earlier by the explorers Willem Schouten and Jacob Le Maire, but the language spoken by these people did not seem to match it. The islanders blew on something that sounded to the Dutch like a Moorish trumpet—no doubt a conch shell—and a pair of Dutch trumpeters responded in turn. Then, as darkness was falling, the parley ended, and the islanders paddled back to shore.

Early the next morning, a canoe came out to the ships. Once again, the islanders called out, and this time the Dutch made signs for them to come aboard, showing them white linen and knives. The men in the canoe could not be persuaded, however, and after a little while they returned to shore. Tasman held a second council, at which it was decided to bring the ships closer inshore, “since there was good anchoring-ground and these people (as it seems) are seeking friendship.” But before the ink was even dry on this resolution, a fleet of seven canoes set out from shore. Two of these took up positions nearby, and when a small boat ferrying men from one of the Dutch ships to the other passed between them, they attacked it, ramming the boat, boarding it, stabbing and clubbing the men, and throwing the bodies overboard. The attack was fast, furious, and effective; three of the Dutch sailors were killed instantly, one was mortally wounded, and three more were eventually rescued from the sea. The sailors on board the ships fired their guns, but they were too far away or too late or just too inaccurate, and the islanders escaped to safety, taking the body of one of the Dutch sailors with them as they went.

Tasman was shocked by the audacity of this attack and by the steady increase in the number of canoes gathering in the bay—first four, then seven, then eleven, and finally twenty-two—and he ordered his men to set sail as quickly as they could. But the islanders were equally determined not to let their quarry escape, and they pursued them right across the bay, abandoning the chase only when a man standing in one of the leading canoes was shot. Tasman christened the place Murderers Bay and made no further attempts to land in New Zealand. He never grasped that the bay in which he had been attacked (now known as Golden Bay) lay at the opening of the large strait that separates the North and South Islands of New Zealand, or that the “continent” he had discovered was in fact two large islands. Thinking that he might have chanced upon some corner of Terra Australis Incognita, he named it Staten Landt and proposed that it might be connected to the Staten Landt named in 1616 by Schouten and Le Maire. This, however, was unlikely, as Schouten and Le Maire’s Staten Landt was an island off the tip of South America, more than five thousand watery miles away.

TASMAN DID AT least get a look at the inhabitants of New Zealand, the people we know today as Māori. He described them as average in height “but rough in voice and bones,” with a complexion that was something “between brown and yellow” and long black hair, which they wore tied up on the tops of their heads in the fashion of the Japanese. Their boats were made from two narrow canoes, “over which some planks or other seating was laid, Such that above water one can see through under the vessel.” Each carried roughly a dozen men, who handled their craft “very cleverly.”

Interestingly, these double-hulled vessels sound a lot like canoes observed by seventeenth-century Europeans in other parts of Polynesia, but by the time the next European reached New Zealand, more than a century later, they were few and far between. What later eighteenth- and nineteenth-century visitors to New Zealand commonly reported were the great waka taua: enormous single-hulled war canoes—up to a hundred feet long, with a breadth of five or six feet—which could carry as many as seventy or eighty men. Nowhere else in Polynesia were single-hulled vessels of such prodigious dimensions ever seen, for the simple reason that nowhere else in Polynesia did trees grow to this size. Carved, whenever possible, from a single trunk, they were designed as coastal and river vessels and were never intended for transoceanic travel.

This apparent evolution in canoe design is a salutary reminder that cultures are not static and that there is a logic to their transformations. If the Māori stopped making double-hulled oceangoing canoes, it must have been because they were no longer sailing across the ocean. But Tasman’s evidence suggests that as late as the mid-seventeenth century, at least in the South Island, the inhabitants of New Zealand were still using vessels of a type that linked them to the rest of Polynesia and to the tradition of long-distance ocean travel.

Tasman departed New Zealand with little more than a dramatic tale about the “detestable deed” committed by its inhabitants and set his ships on a northeast course, which would bring him, in about two weeks’ time, to the islands of Tonga. He was now entering a region of the Pacific with a much higher concentration of islands, a greater population density, and a complex set of relationships among contiguous archipelagoes. Tonga lies a few hundred miles from Samoa, at the western edge of the Polynesian Triangle. Together they constitute the western gateway to Polynesia; here are the oldest Polynesian languages, the longest settlement histories, the deepest Polynesian roots.

Tasman was not the first European to reach this region. The Dutch explorers Schouten and Le Maire had passed through the northern edge of the Tongan archipelago in 1616, stopping at a pair of islands where they traded for coconuts, pigs, bananas, yams, and fish and collected words for their vocabulary. Tasman, coming from the south, made landfall at the southern end of the archipelago, on the island of Tongatapu, where the people he met seemed friendly and eager to trade. He described them as brown-skinned, with long, thick hair, rather taller than average, and “painted Black from the middle to the thighs.” They came out to the ships in large numbers, readily climbing aboard, and relations between the two groups were generally amicable. Tasman was glad of the opportunity to get fresh food and water, but he was careful to keep his men armed, since, as his recent experience in New Zealand had taught him, it is difficult to know “what sticks in the heart.” The Tongans, however, seemed focused on trade, and much of Tasman’s account is given over to detailing the terms: a hen for a nail or chain of beads; a small pig for a fathom of dungaree; ten to twelve coconuts for three to four nails or a double medium nail; two pigs for a knife with a silver band plus eight to nine nails; yams, coconuts, and bark cloth for a pair of trousers, a small mirror, and some beads.

Once again, Tasman tried to use the vocabulary collected by his Dutch predecessors. He reported that he asked specifically about water and pigs—while somewhat confusingly displaying a coconut and a hen—but that the islanders did not seem to understand him. Reading his account, one longs to be able to go back and observe these transactions. Was he using the right part of the vocabulary? How was he pronouncing the words? Did his gestures merely confuse the situation? The story is all the more tantalizing because parts of Schouten and Le Maire’s word list had been collected just a few hundred miles away. For “hog” they had recorded the word “Pouacca,” a quite respectable rendering of the common Polynesian word puaka, meaning “pig.” For “water” they suggested “Waij.” Adjusting for Dutch spelling and pronunciation, this gives something like the English “vie,” which closely resembles a word for “water” in several Polynesian languages. It should have worked, but it didn’t, and a connection that might have been made slipped through the cracks.

IT WAS LEFT to the last of the early Pacific explorers to finally put two and two together. Sailing from the Netherlands in 1721, the Dutch navigator Jacob Roggeveen rounded Cape Horn and began making his way up the South American coast. For decades there had been talk of an island, or a chain of islands, or even a high continental coast somewhere in the southeastern Pacific. Many had gone looking for the country known as Davis’s Land (after a putative sighting by a seventeenth-century English buccaneer), and Roggeveen was determined to find it. Leaving the coast of South America, he plowed on through seventeen hundred miles of empty ocean, and on Easter Sunday 1722 he caught sight of what would turn out to be the most isolated inhabited island in the world.

Easter Island, or Rapa Nui, to use its modern Polynesian name, lies in the middle of a three-million-square-mile circle of empty sea. Its nearest neighbors, more than a thousand miles to the west, are tiny Henderson Island and even tinier Pitcairn, neither of which was inhabited when Europeans reached the Pacific, though both showed signs of prehistoric occupation. Easter Island is nominally a high island, but it is small, old, heavily weathered, and dry; it has no rivers, uncertain rainfall, and no protective coral reef. Difficult to inhabit and even more difficult to find, it constitutes the southeastern vertex of the Polynesian Triangle and represents the farthest known extension of Polynesian culture to the east.

At first, Roggeveen believed it to be “the precursor of the extended coast of the unknown Southland,” but the Dutch were destined to be disappointed on numerous fronts. What looked from a distance like golden dunes turned out to be “withered grass” and “other scorched and burnt vegetation.” The fine, multicolored clothes in which the islanders at first appeared to be dressed proved, on closer inspection, to be made of pounded tree bark dyed with earth, while the “silver plates” the Dutch thought they saw in their ears were made from something resembling a parsnip. Roggeveen wrote that he was struck by the “singular poverty and barrenness” of the island. It was not that nothing would grow—the inhabitants seemed well enough supplied with bananas, sugarcane, taro, and sweet potato—but rather that the island was entirely devoid of trees. This was puzzling on many fronts, but especially because it was unclear how, without any kind of strong and heavy wood to use as levers, rollers, or skids, the islanders could have erected their great stone statues—the famous moai of Easter Island.

These monolithic sculptures, with their long, sloping, oversize heads, upturned noses, and thin, pouting lips, are by now almost as familiar as the pyramids of Giza and perhaps more challenging to explain. The average moai stands about fourteen feet tall and weighs around twelve tons, but some are twenty to thirty feet in height, and the largest, had it been completed, would have stood seventy feet tall and weighed 270 tons. They are made from a kind of solidified ash known as volcanic tuff, and nearly half of the roughly nine hundred known statues still lie in the quarry where they were carved. A third were transported to various locations around the island, where they were erected on stone platforms and topped with stone hats, while the remainder lie scattered about the island, seemingly abandoned en route.

Roggeveen may have been the first, but he was by no means the last person to wonder how these statues had been erected. Indeed, the mystery of the Easter Island moai—what they meant, why they were carved, why their production abruptly ceased (there are half-finished moai in the quarry that are still attached to the rock), but especially how they were maneuvered into place—has inspired all kinds of speculation. People have tried to show how the statues might have been moved using only locally available materials: rocking them from side to side and walking them forward; sliding them on banana palm rollers; dragging them along on sledges suspended under wooden frames. The main problem, as Roggeveen noted in 1722, is the absence of everything that might have been needed to move a ten- or twenty- or thirty-ton block of stone: wheels, metal, draft animals, cordage, but most obviously timber.

Although Roggeveen found the island essentially barren of trees, modern studies of pollen found in sediment cores and archaeological finds of fossil palm nuts, root molds, and fragments of charcoal show that Easter Island was once home to a variety of tree species. Some twenty-two now vanished species have been identified, including the oceanic rosewood, the Malay apple, and something resembling the Chilean wine palm, which on the South American mainland grows to a height of sixty-five feet. Some of these trees would have produced edible fruit, others would have been good for making fires, at least two are known to have been suitable for making canoes, and still others produce bark that is used for making rope in other parts of Polynesia. Taken together, they would have constituted an entire arboreal foundation for human existence, not to mention a habitat for many now extinct species of birds.

Exactly what happened to all these trees is unknown, and there is a vigorous debate about the cause of what has been described as “the most extreme example of forest destruction in the Pacific, and among the most extreme in the world.” One argument points to the island’s ecological fragility and its vulnerability to changes brought about by humans. Sediment cores on Easter Island reveal dramatic increases in erosion and charcoal particles around A.D. 1200. This is often taken as a proxy for human activity in the Pacific, where slash-and-burn agriculture was widely practiced, and it has been used to support the argument that Easter Island’s ecological collapse began with the arrival of the first Polynesian settlers.

According to this view, the original colonizers began felling trees and clearing land for gardens and plantations as soon as they arrived. On a different island—one that was wetter, warmer, younger, larger, or closer to other landmasses—such activities might have altered the island’s ecology without destroying it. But Easter Island is a uniquely precarious environment. The slow-growing trees were not quickly replaced, while the loss of the canopy exposed already poor soils to “heating, drying, wind, and rain.” This, in turn, led to erosion, the loss of topsoil, and a general decrease in the island’s fertility. Each step in the degradation of the environment led to the next, and once the damage reached a certain level, there was no going back. Others—partly in response to the disturbing image of some desperate and improvident Easter Islander chopping down the last palm tree—have argued that the island’s deforestation was caused not by the islanders themselves but by their commensals, in particular the Polynesian rat. It was the rat, they argue, with its taste for nuts, seeds, and bark, its lack of predators, its climbing ability, and its fast rate of reproduction, that spelled doom for the virgin forests on Rapa Nui.