Полная версия

Sea People

Of course, there were lots of things the early explorers did not see, and many of their accounts are maddeningly superficial. Early visitors to the Marquesas saw none of the monumental architecture and sculpture that links that archipelago to both Tahiti and Easter Island. Early visitors to Easter Island reported the presence of “stone giants” but were confusing on the question of how easy it was to grow food. And the first European visitors to New Zealand saw nothing, being too scared of the Māori to go ashore.

Much has been made in histories of the Pacific about the problem of observer bias. Early European explorers saw the world through lenses that affected how they interpreted what they found. The Catholic Spanish and Portuguese of the sixteenth century were deeply concerned with the islanders’ heathenism; the mercantile Dutch, in the seventeenth century, were preoccupied by what they had to trade; the French, coming along in the eighteenth century, were most interested in their social relations and the idea of what constituted a “state of nature.” Still, the project on which these explorers were embarked was, very broadly speaking, an empirical one; their primary task was to discover what was out there and report back about what they had seen. Naturally, there were other agendas: territorial expansion, political advantage, conquest, commerce. But on a quite fundamental level, the project was one of observation and reportage, and, for the most part, they got better at it as the centuries wore on.

There was, however, one really big mistake that all the early European explorers in the Pacific made, one that blinded them to the true character of the region for ages. It was essentially a geographical error, and the best way to understand it is by looking at early European maps.

THE FIRST EUROPEAN maps of the world, the so-called Ptolemaic maps of the fifteenth century, do not even include Oceania, or what Cook would later call “the fourth part” of the globe. Their focus is on the known, inhabited regions of the world, which means, at this stage of history, that there is nothing west of Europe, east of Asia, or south of the Tropic of Capricorn. This all changed with the discovery of the Americas, and maps of the sixteenth century show a world that is already quite recognizable. The outlines of Europe, Asia, and Africa all look surprisingly correct, and even the New World, though distorted, bears a better-than-passing resemblance to North and South America as we know them today.

The Pacific in this period is still something of a cipher. Virtually all the major archipelagoes are missing, California is sometimes depicted as an island, and the continent of Australia is often drawn as though it were a peninsula of something else. The large island of New Guinea is frequently represented at twice its real size, and the Solomon Islands, discovered in 1568 and then lost for almost exactly two hundred years, are not only grossly exaggerated but seemingly untethered. On some maps they are located in the western Pacific, where they belong, but on others they have floated right out into the middle of the ocean, a clear reflection of the fact that for centuries no one had the foggiest idea where they actually were.

But the most remarkable feature of maps from this period is the presence of an enormous landmass, greater than all North America, Europe, and Asia combined, wrapped around the southern pole. This continent, known as Terra Australis Incognita, or “the Unknown Southland,” occupies nearly a quarter of the globe. It is as if Antarctica included both Tierra del Fuego and Australia, stretched almost to the Cape of Good Hope, and reached so far into the Indian and Pacific Oceans that it entered the Tropic of Capricorn.

Terra Australis Incognita was one of the great follies of European geography, an idea that made sense in the abstract but for which there was never any actual proof. It was based on a bit of Ptolemaic logic handed down from the ancient Greeks, which held that there must be an equal weight of continental matter in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres, or else the world would topple over and, as the great mapmaker Gerardus Mercator envisioned it, “fall to destruction among the stars.” This idea of global symmetry was inherently appealing, but it also made intuitive sense to Europeans, who, coming from a hemisphere crowded with land, found it difficult to imagine that the southern reaches of the planet might be as empty as they really are.

Like many imaginary places, Terra Australis Incognita—or, as it was sometimes more optimistically known, Terra Australis Nondum Cognita, “the Southland Not Yet Known”—represented not just what Europeans thought ought to exist in the Pacific but what they wanted to find. It was conflated with a whole range of utopian fantasies: lands of milk and honey, El Dorados, terrestrial paradises. Almost from the beginning, it was linked with the land of Ophir, the source of the biblical King Solomon’s wealth, which explains why there are Solomon Islands in the neighborhood of New Guinea. Other rumors connected it with the mythical lands of Beach, Lucach, and Maletur, said to have been discovered by Marco Polo, and with the fabled islands of the Tupac Inca Yupanqui, from which he was said to have brought back slaves, gold, silver, and a copper throne.

For nearly three hundred years, the idea of Terra Australis Incognita drove European exploration in the Pacific, shaping the itineraries and experiences of voyagers, who were convinced that if they just kept looking, they would find a continent somewhere in the southern Pacific Ocean. Of course, there is a continent there—Antarctica—but it is not the kind of continent that Europeans had in mind. They were hoping for something bigger and more temperate, greener and more lush, richer and more hospitable, inhabited by people with fine goods for trade. They were dreaming of another Indies, or, failing that, another New World. But despite the “green drift” reported at 51 degrees south by the Dutch explorer Jacob Le Maire, and the birds he claimed to have seen in the roaring forties, and the mountainous country resembling Norway reported at 64 degrees south by Theodore Gerrards, despite the buccaneer Edward Davis’s rumors, and Pedro Fernández de Quirós’s claim of a country “as great as all Europe & Asia,” no continent resembling Terra Australis Incognita ever appeared.

What European navigators found in the Pacific instead was water—vast, unbroken stretches of water extending in every direction as far as the eye could see. For days on end, for weeks, sometimes for months, they sailed on the great circle of the ocean with nothing above them but the vault of the sky and nothing between them and the horizon but “the sea with its labouring waves for ever rising, sinking, and vanishing to rise again.” No distant smudges, no piles of clouds, no sea wrack, sometimes not even any birds. And then, just when they had begun to think they might sail onward to the end of eternity, an island would rise up over the rim of the world.

First Contact

Mendaña in the Marquesas

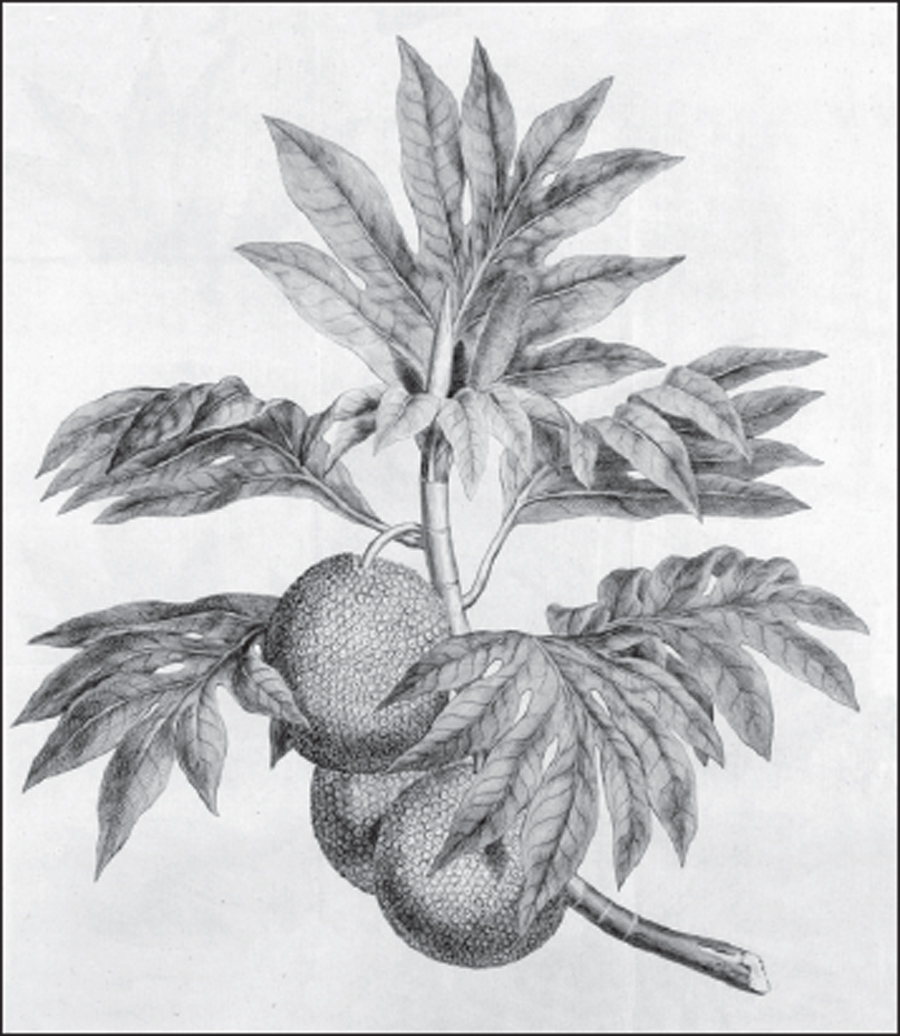

Breadfruit, after a drawing by Sydney Parkinson, in John Hawkesworth, An Account of the Voyages (London, 1773).

DEPARTMENT OF RARE BOOKS AND SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, PRINCETON UNIVERSITY LIBRARY.

IF WE SET aside Magellan’s two little atolls, both of which were uninhabited at the time, the first Polynesian island to be sighted by any European was in the Marquesas. This is a group of islands just south of the equator and about four thousand miles west of Peru, a location that puts them at the eastern edge of the Polynesian Triangle, in a comparatively empty region of the sea. To the west and south they have neighbors within a few hundred miles, but you could sail north or east from the Marquesas along a 180-degree arc and not meet with anything at all for thousands of miles.

The islands of Polynesia come in different varieties, and the Marquesas are what are known as “high islands.” What this means to a layperson is that they are mountainous, rising in some cases thousands of feet from the sea; what it means to a geologist is that they are volcanic in origin. Some high islands occur in arcs, in places where one tectonic plate plunges underneath another. But those of the mid-Pacific are thought to be formed by hot spots, plumes of molten rock rising directly from the earth’s mantle. These islands typically occur in chains, grouped along a northwest–southeast axis, with the oldest at the northwest end and the youngest at the southeast, a pattern explained by the northwesterly movement of the Pacific plate. The idea is that over the course of millions of years, islands are formed and carried away as the slab of crust on which they are sitting drifts, while new islands rise out of the ocean behind them. The textbook case is the Hawaiian archipelago: the Big Island of Hawai‘i, with its active volcanoes, lies at the southeastern end of a chain of islands that get progressively older and smaller as they trail away to the northwest, ending in a string of underwater seamounts. Meanwhile, southeast of the Big Island, a new volcano is emerging, which will crest the sea sometime in the next 100,000 years.

The landscape of a high island has a sort of yin and yang about it. Composed almost entirely of basalt, high islands erode in quite spectacular ways, exposing great ribs and ramparts and pinnacles of rock. On their windward sides, where the mountains wring moisture from the passing air, they are lush and verdant, while on their leeward sides, in the rain shadow of these same mountains, they can be perfectly parched. But perhaps the greatest contrast is between the dark, heavy loom of the mountains and the bright, open aspect of the sea. Out from under the shadow of the peaks, the tangle of trees and vines in the uplands gives way to an airier landscape of grasses, coconut palms, and whispering casuarina. The ridges flatten to a coastal plain; the mountain cataracts slow to quiet rivers. At the tide line, the rocks and pools give way, here and there, to bright crescents of sand. The sea stretches out into the distance, broken only by a line of white breakers where the reef divides the bright turquoise of the lagoon from the darker water of the open ocean.

In some respects, the Marquesas are typical high islands, with their towering rock buttresses and fantastic spires, their deeply eroded clefts and fertile valleys. But in others they are quite unlike the Polynesian islands pictured in tourist brochures. Lying in the path of the Humboldt Current, which carries cold water up the South American coast, the Marquesas have never developed a system of coral reefs. They have no lagoons, few sheltered bays, and only a handful of beaches. Their ruggedness extends all the way to the coast, and their shores are largely grim and perpendicular.

The other thing missing in the Marquesas is the coastal plain. This is the part of a high island on which it is easiest and most natural to live. As anyone who has been to the islands of Hawai‘i knows, the standard way of navigating a high island is to travel around the coast. And it is easy to see how important this part of the island’s topography is—how it enables movement and communication, provides room for gardens, plantations, and housing; how even now the land between the ocean and the mountains is where the human population lives. In the Marquesas, however, there is none of this; the only habitable land lies in the valleys that radiate out from the island’s center, enclosed and cut off from one another by the mountains’ great arms.

To many Europeans, the Marquesas have seemed indescribably romantic. With their peaks shrouded in mist, their folds buried in greenery, their flanks rising dramatically from the sea, they have a brooding prehistoric beauty. Visiting in 1888, the writer Robert Louis Stevenson found them at once magnificent and forbidding, with their great dark ridges and their towering crags. “At all hours of the day,” he wrote, “they strike the eye with some new beauty, and the mind with the same menacing gloom.”

It is tempting to imagine that the first Polynesians might have had similarly mixed impressions when they arrived. The discovery of any high island in the Pacific must have been a triumph: here was land, water, safety, sources of food. But archaeological sites in the Marquesas reveal a surprising variety of types of fishhooks from the very earliest settlement period, suggesting, perhaps, a surge of experiment and innovation prompted by the realization that fishing techniques brought from islands with more coral would not work in the deep, rough waters of the Marquesan coast. Still, the animals that were imported thrived (except for, maybe, the dog), the breadfruit trees grew, and the people prospered—so much so that by the time the first Europeans arrived, the Marquesas were “thickly inhabited” by a population that came out to meet the strangers in droves.

THE MARQUESAS WERE discovered in 1595 by the Spaniard Álvaro de Mendaña, who was en route with a shipload of colonists to the Solomon Islands. We say that Mendaña “discovered” the Marquesas, but of course this is not, strictly speaking, true. Indeed, the claim that any European explorer discovered anything in the Pacific—least of all the islands of Polynesia—is obviously problematic. As the Frenchman who later claimed the Marquesas for King Louis XV observed, it is hard to see how anyone could possess an island that is already possessed by the people who live there. And what is true for possession is even more true for discovery: In what sense can a land that is already inhabited be discovered? But what the word “discovered” means in the context of eighteenth-century Frenchmen or sixteenth-century Spaniards is not “discovered for the first time in human history” but something much more like “made known to people outside the region for the first time.”

This was Mendaña’s second voyage across the Pacific. Nearly thirty years earlier, he had led another expedition in search of Terra Australis Incognita, managing to reach the Solomon Islands before returning, in some disarray, to Peru. Despite the hardships of the journey, cyclones, scurvy, insubordination, shortages of food and water—at one point the daily ration consisted of “half a pint of water, and half of that was crushed cockroaches”—Mendaña was determined to try again. For twenty-six years he pestered the Spanish crown, and in 1595 they finally gave in.

The second expedition was, if possible, even more calamitous than the first. Confused and disorderly from the start, it was plagued by violence and dissension. Mendaña was on a zealot’s mission to bring the benighted heathen to God; his wife, an unlovable virago, caused trouble wherever she went; many of his soldiers were self-interested and cruel. Neither the commander nor any of his subordinates seem to have understood just how far away their destination was, despite—at least in Mendaña’s case—having been there before. In fact, they never did arrive. The colony, established instead on the island of Santa Cruz, was a disaster, with robberies, murders, ambushes, even a couple of beheadings. Mendaña, ill, broken, and “sunk in a religious stupor,” contracted a fever and died like something out of Aguirre, the Wrath of God. The rest of the expedition disbanded and sailed for the Philippines.

We have the story from Mendaña’s pilot, Pedro Fernández de Quirós, who recorded that just five weeks after setting out from the coast of South America, they sighted their first body of land. Believing this to be the island he was seeking, Mendaña ordered his crew to their knees to chant the Te Deum laudamus, giving thanks to God for a voyage so swift and untroubled. This, of course, was ridiculous; the Solomons were still four thousand miles away, at a minimum another five weeks’ sailing. But it does illustrate just how poorly these early European navigators understood the size of the Pacific and how easily misled they could be. Eventually, Mendaña realized his mistake and after some consideration concluded that this was, in fact, an entirely new place.

The island, which was known to its inhabitants as Fatu Hiva, was the southernmost of the Marquesas, and as the Spanish approached, a fleet of about seventy canoes pulled out from shore. Quirós noted that these vessels were fitted with outriggers, a novelty he carefully described as a kind of wooden structure attached to the hull that “pressed” on the water to keep the canoe from capsizing. This was something many Europeans had not seen, but the development of the outrigger, which can be traced back as far as the second millennium B.C. in the islands of Southeast Asia, was the key innovation that made it possible for long, narrow, comparatively shallow vessels (i.e., canoes) to sail safely on the open ocean.

Each of the Marquesan canoes carried between three and ten people, and many more islanders were swimming and hanging on to the sides—altogether, thought Quirós, perhaps four hundred souls. They came, he wrote, “with much speed and fury,” paddling their canoes and pointing to the land and shouting something that sounded like “atalut.” The anthropologist Robert C. Suggs, who did fieldwork in the Marquesas in the 1950s, thinks they were telling Mendaña to bring his ships closer inshore—“a friendly bit of advice,” as he puts it, “from one group of navigators to another.” Or maybe it was a strategy to get them to a place where they could be more effectively contained.

Quirós wrote that the islanders showed few signs of nervousness, paddling right up to the Spanish ships and offering coconuts, plantains, some kind of food rolled up in leaves (probably fermented breadfruit paste), and large joints of bamboo filled with water. “They looked at the ships, the people, and the women who had come out of the galley to see them . . . and laughed at the sight.” One of the men was persuaded to come aboard, and Mendaña dressed him in a shirt and hat, which greatly amused the others, who laughed and called out to their friends. After this, about forty more islanders clambered aboard and began to walk about the ship “with great boldness, taking hold of whatever was near them, and many of them tried the arms of the soldiers, touched them in several parts with their fingers, looked at their beards and faces.” They appeared confused by the Europeans’ clothing until some of the soldiers let down their stockings and tucked up their sleeves to show the color of their skin, after which, Quirós wrote, they “quieted down, and were much pleased.”

Mendaña and some of his officers handed out shirts and hats and trinkets, which the Marquesans took and slung round their necks. They continued to sing and call out, and as their confidence increased, so did their boisterousness. This, in turn, annoyed the Spanish, who began gesturing for them to leave, but the islanders had no intention of leaving. Instead they grew bolder, picking up whatever they saw on deck, even using their bamboo knives to cut slices from a slab of the crew’s bacon. Finally, Mendaña ordered a gun to be fired, at which the islanders all leapt into the sea—all except one, a young man who remained clinging to the gunwale, refusing, either out of obstinance or terror, to let go until one of the Spaniards cut him with a sword.

At this, the tenor of the encounter changed. An old man with a long beard stood up in his canoe and cried out, casting fierce glances in the direction of the ships. Others sounded their shell trumpets and beat with their paddles on the sides of their canoes. Some picked up their spears and shook them at the Spaniards, or fitted their slings with stones and began hurling them at the ship. The Spaniards aimed their arquebuses at the islanders, but the powder was damp and would not light. “It was a sight to behold,” wrote Quirós, “how the natives came on with noise and shouts.” At last, the Spanish soldiers managed to fire their guns, hitting a dozen or so of the islanders, including the old man, who was shot through the forehead and killed. When they saw this, the islanders immediately turned and fled back to shore. A little while later, a single canoe carrying three men returned to the ships. One man held out a green branch and addressed the Spaniards at some length; to Quirós he seemed to be seeking peace. The Spanish made no response, and after a little while the islanders departed, leaving some coconuts behind.

THE ENCOUNTERS BETWEEN the Marquesans and Mendaña’s people were filled with confusion, and many “evil things,” wrote Quirós, happened that “might have been avoided if there had been someone to make us understand each other.” In this, it was like many early encounters between Europeans and Polynesians: everything that happened made sense to someone, but much of it was baffling, offensive, or even deadly to those on the other side.

In one incident, four “very daring” Marquesans made off with one of the ships’ dogs; in another, a Spanish soldier fired into a crowd of canoes, aiming at and killing a man with a small child. On shore, Mendaña ordered a Catholic mass to be held, at which the islanders knelt in imitation of the strangers. Two Marquesans were taught to make the sign of the cross and to say “Jesus, Maria”; maize was sown in the hope that it might take. Mendaña’s wife, Doña Isabel, tried to cut a few locks from the head of a woman with especially beautiful hair but was forced to desist when the woman objected—the head, being tapu, should not have been touched, as hair was known to be useful for sorcery.

Three islanders were shot and their bodies hung up so that the Marquesans “might know what the Spaniards could do.” Mendaña envisioned establishing a colony, leaving behind thirty men along with some of their wives. But the soldiers adamantly refused this mission. Perhaps they understood, no doubt correctly, that it would have been more than their lives were worth, for by the time the Spanish finally departed, they had killed more than two hundred people, many, according to Quirós, for no reason at all.

Quirós was distressed by the cruel and wanton behavior of Mendaña’s men. In the islanders, on the other hand, he found much to admire. Indeed, it is through Quirós’s eyes that we get our first glimpse of a people who would come to epitomize for many Europeans the pinnacle of human beauty. One later visitor described the Marquesans as “exquisite beyond description” and the “most beautiful people” he had ever seen. Even Cook, a man never given to exaggeration, called them “as fine a race of people as any in this Sea or perhaps any whatever.”

The islanders, wrote Quirós, were graceful and well formed, with good legs, long fingers, and beautiful eyes and teeth. Their skin was clear and “almost white,” and they wore their hair long and loose “like that of women.” Many were naked when he first saw them—they were swimming at the time—and their faces and bodies were decorated with what Quirós at first took to be a kind of blue paint. This, of course, was tattooing, a practice common across Polynesia—the English word “tattoo” is derived from the Polynesian tatau—but carried to the peak of perfection in the Marquesas, where every inch of the body, including the eyelids, tongue, palms of the hands, even the insides of the nostrils, might be inscribed. Quirós found the Marquesan women, with their fine eyes, small waists, and beautiful hands, even more lovely “than the ladies of Lima, who are famed for their beauty,” and characterized the men as tall, handsome, and strong. Some were so large that they made the Spaniards look diminutive by comparison, and one made a great impression on the visitors by lifting a calf up by the ear.

Ethnographically speaking—remembering that this is the earliest recorded description of any Polynesian society that we have—Quirós’s account is slim but interesting. The Marquesans, he wrote, had pigs and chickens (“fowls of Castille”), as well as plantains, coconuts, calabashes, nuts, and something the Europeans had never seen, which they described as a green fruit about the size of a boy’s head. This was breadfruit, a plant that would enter Pacific legend two centuries later as the cargo carried by Captain William Bligh of the Bounty when his crew mutinied off the island of Tahiti. (Bligh was carrying the breadfruit seedlings to the West Indies, where, it was envisioned, they would provide an economical means of feeding African slaves.) They lived in large communal houses with platforms and terraces of neatly fitted stone and worshipped what the Spanish referred to as an “oracle,” an enclosure containing carved wooden figures to whom they made offerings of food. Their tools were made of stone and shell; their primary weapons were spears and slings. Their most significant manufactures were canoes, which they made in a variety of sizes: small ones with outriggers for three to ten paddlers, and large ones, “very long and well-made,” with room for thirty or more. Of the latter wrote Quirós, “They gave us to understand, when they were asked, that they went in these large canoes to other lands.”