Полная версия

Sea People

What lands these might have been remained a mystery, however. In one curious incident, the Marquesans, seeing a black man on one of the Spanish ships, gestured toward the south, making signs “to say that in that direction there were men like him, and that they went there to fight, and that the others had arrows.” This is a baffling remark, and quite typical of the sort of misdirection that is rampant in these early accounts. While it might describe any number of people in the islands far to the west, the bow was never used as a weapon in Polynesia. The only places south of the Marquesas are the Tuamotu Archipelago, and, even farther away, Easter Island—all of whose inhabitants are culturally and physically quite similar to Marquesans. They might well have been perceived as enemies, but they were not archers and they were not black.

But while we have no idea which islands Quirós was referring to, we do know that there were “other islands” in the Marquesans’ conceptual universe. Later visitors heard tell of “islands which are supposed by the natives to exist, and which are entirely unknown to us.” It was also reported that in times of drought, “canoes went out in search of other islands,” which may help explain why, when Cook reached the Marquesas in 1775, the islanders wondered whether he had come from “some country where provisions had failed.”

MENDAÑA REMAINED IN the Marquesas for about two weeks, in the course of which he identified and named the four southernmost islands in the archipelago. (A second cluster of islands lay undiscovered to the north.) He called them, after his own fashion, Santa Magdalena, San Pedro, La Dominica, and Santa Cristina, names that have all long been replaced by the original Polynesian names: Fatu Hiva, Motane, Hiva Oa, and Tahuata. The archipelago as a whole he named in honor of his patron, Don García Hurtado de Mendoza, Marquis of Cañete and viceroy of Peru, and in all the years since 1595 the Marquesas have never been known as anything else. Except, of course, among the islanders themselves, who know their islands collectively as Te Fenua, meaning “the Land,” and themselves, the inhabitants of Te Fenua, as Te Enata, meaning simply “the People.”

When Mendaña’s ships finally sailed away, the Marquesas were lost again to the European world for nearly two hundred years. They had been none too securely plotted to begin with, and their location was further suppressed by the Spanish in order to forestall competition in the search for Terra Australis Incognita. Privately, if the Spanish concluded anything, it was that the Marquesas, with their large, vigorous population of beautiful people, their pigs, their chickens, and their great canoes, proved the existence of a southern continent. Lacking “instruments of navigation and vessels of burthen,” Quirós concluded, the inhabitants of these islands could not possibly have made long-distance ocean crossings. This meant that somewhere in the vicinity there must be “other islands which lye in a chain, or a continent running along,” since there was no other place “whereby they who inhabit those islands could have entered them, unless by a miracle.” Thus the irony of first contact between Polynesia and Europe: that it served to reinforce a hallucinatory belief in the existence of an imaginary continent while obscuring the much more intriguing reality of the Marquesans themselves.

Barely an Island at All

Atolls of the Tuamotus

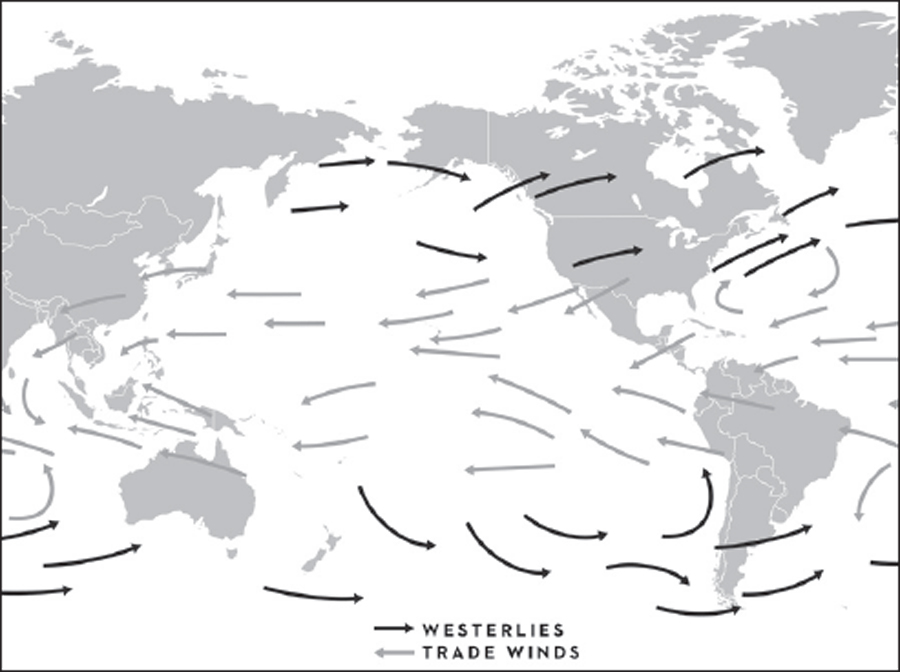

Winds in the Pacific, based on “Map of the prevailing winds on earth,” in Het handboek voor de zeiler by H. C. Herreshoff, adapted by Rachel Ahearn.

WIKIMEDIA COMMONS.

MENDAÑA DISCOVERED THE Marquesas because he sailed west in roughly the right latitude from the port of Paita, in the Spanish viceroyalty of Peru. But those who came after set sail from different ports and followed different routes and, thus, discovered different sets of islands. This was not so much a matter of intention: European explorers in the sixteenth and seventeenth and even eighteenth centuries did not have the freedom to go wherever they wished. On the contrary, for some centuries virtually all their discoveries were determined by the distinctive pattern of the winds and currents in the Pacific Ocean and by the limited points of entry into the region from other parts of the world.

The weather in the Pacific is dominated by two great circles of wind, or gyres, one of which turns clockwise in the Northern Hemisphere, while the other turns counterclockwise in the Southern. Across wide bands from roughly 30 to 60 degrees in both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres, the winds are predominantly westerly, that is, they blow from west to east. In the north, these winds sweep across the continents of Europe, Asia, and North America. But in the Southern Hemisphere, where there are few landmasses to impede them, they can reach fantastic speeds—hence the popular names for the far southern latitudes: the “roaring forties,” “furious fifties,” and “screaming sixties.”

From the equator to about 30 degrees north and south—roughly across the Tropics of Capricorn and Cancer—the winds predominantly blow the opposite way. These are known as the trade winds, a reliable pattern of strong, steady easterlies with a northeasterly slant in the Northern Hemisphere and a southeasterly slant in the Southern. In between, in the vicinity of the equator itself, is an area known as the Intertropical Convergence Zone, or ITCZ, a region of light and variable winds and frequent thunderstorms more commonly known as the Doldrums and greatly feared by early European navigators for its deadly combination of stultifying heat and protracted calms. Anyone who has flown across the equator in the Pacific—say, from Los Angeles to Sydney—may remember a bumpy patch about halfway through the flight; that was the ITCZ.

The major ocean currents in the Pacific follow basically the same pattern, flowing west along the equator and peeling apart at the ocean’s edge, turning north in the Northern Hemisphere and south in the Southern and circling back around in two great cells. There is, however, also something called the Equatorial Countercurrent, which flows eastward along the equator in between the main westward-flowing northern and southern currents—just to make things confusing.

What all this meant for ships under sail was that near the equator things could be quite chaotic, and often there would be no wind at all. In the tropics, the winds and currents would, generally speaking, speed a ship on its way west, permit it to sail on a north–south axis, and effectively prevent it from sailing east the vast majority of the time. Thus, if one wanted to proceed eastward across the Pacific, the only sure way to do it was to travel in higher, colder latitudes (that is, farther north or south), where sailors typically encountered the opposite problem: the inability to make any westing at all.

The other major constraint on early Pacific navigation for Europeans was the problem of entry points. In the days before the man-made shortcuts of Panama and Suez, European ships bound for the Pacific were forced to sail to the very bottom of the world and around either Africa or South America in order to reach the Pacific Ocean. The eastern route, by way of Africa, was by far the longest; not only did one have to sail all the way south and around the Cape of Good Hope, but then there was still the whole Indian Ocean to cross, and beyond that the mysterious impediment of Australia. The western route, by way of South America, was shorter and therefore more attractive, but it also presented the greatest danger, in the form of a passage around the dreaded Cape Horn. Here, where the long tail of South America reaches almost to the Antarctic ice, lies one of the most fearsome stretches of ocean in the entire world. It combines furious winds, enormous waves, freezing temperatures, and a shelving, ironbound coast to produce what can only be described as a navigator’s nightmare: a maelstrom of wind, rain, sleet, snow, hail, fog, and some of the world’s shortest and steepest seas.

Stories of dreadful passages around Cape Horn are legion. Leading a squadron of eight ships around the Horn in the early 1740s, Britain’s Commodore George Anson was battered for a biblical forty days and forty nights by a succession of hurricanes so wild they reduced his crew to gibbering terror. Two of the squadron’s ships went missing, effectively blown away by the wind, and Anson was ultimately forced to resort to the hideous expediency of “manning the foreshrouds,” that is, sending men into the rigging to act as human sails, the wind being too ferocious to permit the carrying of any actual canvas. Needless to say, at least one seaman was blown from his perch. A strong swimmer, he survived for a while in the icy water, but such was the intensity of the storm that his shipmates were forced to watch helplessly as he was swept away by the mountainous seas.

Forty-odd years later, Captain Bligh of the Bounty encountered a similar series of storms as he tried to round the Horn on his way to Tahiti, on the voyage that would famously end in mutiny. For a month he battled winds that boxed the compass and was drenched by seas that broke over his ship. At the end of a titanic struggle against “this tempestuous ocean,” he finally surrendered. Turning east, he got the wind behind him and bore away for Africa and the Cape of Good Hope, a decision that would add ten thousand miles to his voyage.

There was an alternative to rounding the Horn, and that was to pass through the Strait of Magellan, the route pioneered in 1520 and the earliest known pathway into the Pacific from the Atlantic side. But this narrow, twisting passageway of some 350 miles, which separates the archipelago of Tierra del Fuego from mainland South America, presents navigational challenges of its own. Here the problem is not so much exposure as the complicated nature of the passage itself and unpredictable winds and currents. Magellan himself had been unusually fortunate, making the passage in only thirty-eight days, but the British navigator Samuel Wallis spent more than four months trying to clear the strait in 1767, giving him an effective sailing rate of less than three miles a day.

The Strait of Magellan opens out into the Pacific between 52 and 53 degrees south latitude. Cape Horn lies at approximately 56 degrees south, and navigators who decided to sail around it were routinely obliged to sail into the high fifties; Cook reached as far as 60 degrees south on his first passage round the Horn. But, either way, once they had made it into the Pacific, navigators found it almost impossible to advance. They could make no headway in these latitudes against the ferocious westerly winds. Southward lay the ice and snow—they were nearly to the Antarctic Circle—east was the coast of South America, and the only direction open to them was north.

It is this particular set of circumstances—winds, distances, continental obstacles, and sailing capacity—that explains a curious fact about early European encounters in the Pacific, which is that, even with the whole, wide ocean before them, almost all the early navigators followed variants of the same route. With one or two exceptions, they crossed the South Pacific on a long northwesterly diagonal, or, more properly, a dogleg, sailing north and then turning west once they picked up the trades. They did this not because they thought it was the path most likely to yield important discoveries—as the historian J. C. Beaglehole drily observed, “sailing on some variant of the great north-west line, of necessity a ship made through a vast deal of empty ocean”—but because it was the path dictated by the currents and the winds. As a consequence, many important islands that lie off this route, like Hawai‘i, were not encountered for centuries, while others, some of them minuscule, like the tiny atoll of Puka Puka in the Tuamotu Archipelago, were discovered over and over again.

THE TUAMOTUS, ALSO known as the Low or Dangerous Archipelago, feature in almost every early European account of the Pacific, for the simple reason that they lie directly across most variants of the great northwest line. A screen of some seventy-eight “low islands,” or atolls, the Tuamotus stretch for eight hundred miles along a northwest–southeast axis about halfway between the Marquesas and Tahiti. Most of these atolls are comparatively small, on average perhaps ten to twenty miles wide, but their key feature, at least from a navigator’s point of view, is their height. None of these islands reach an elevation of more than twenty feet; most are barely twelve feet above the tide line at their highest point. They are, as Stevenson put it, “as flat as a plate upon the sea.” What this means for sailors is that they are invisible until one is all but upon them, and later navigators, who knew more about what they were getting into, tended to avoid this maze of reefs and islands that was also sometimes known as the Labyrinth.

From the air, the Tuamotus are a dazzling sight: bright circlets of green and white floating like diadems in a sapphire sea. But, as the early explorers quickly discovered, up close there is not much to an atoll. Barely an island at all, it is really a necklace of islets, or motu, to use the Polynesian word, strung along a circle of reef. The motu are composed entirely of coral: sand, cobbles, coral blocks, and a kind of conglomerate known as beachrock. Verdant from a distance, they in fact have only the thinnest layer of topsoil and can support just a few salt-tolerant species of shrubs and trees. There are no natural sources of fresh water apart from rain, though there is an interesting phenomenon known as a Ghyben-Herzberg lens. This is a layer of fresh water which floats on top of the seawater that infiltrates the porous coral rock. Under the right conditions—the island cannot be too small, it cannot be in a state of drought, the well cannot be dug too deep—it is possible to extract fresh water from a pit dug into the sand, as a group of seventeenth-century Dutch sailors accidentally discovered on an atoll they named Waterlandt.

It was Charles Darwin who first articulated the theory of how coral atolls are formed. On his way across the Pacific in the Beagle, Darwin sailed through the Tuamotu Archipelago, recording his first impression of an atoll as seen from the top of the ship’s mast. “A long and brilliantly white beach,” he wrote, “is capped by a margin of green vegetation; and the strip, looking either way, rapidly narrows away in the distance, and sinks beneath the horizon. From the mast-head a wide expanse of smooth water can be seen within the ring.” It was already understood in Darwin’s day that corals were creatures—“animalcules,” as one writer put it—and that they could grow only in comparatively shallow water. And yet, here they were in the middle of the ocean, in a place where the water was so deep it could not be measured by any conventional means. (The Dutch named a second atoll Sonder Grondt, i.e., “Bottomless,” because they could find no place to anchor.) The obvious question concerned their foundation, or, as Darwin put it, “On what have the reef-building corals based their great structures?”

One theory popular at the time was the idea that atolls grew up on the rims of submerged volcanic craters. There were good reasons for associating them with vulcanism—high islands and low islands are found in close proximity throughout the Pacific. But there were also problems with the crater idea: some large atolls exceed the size of any known volcanic craters; some small atolls exist in clusters that cannot easily be envisioned as craters; and many volcanic islands are closely surrounded by coral reefs, which, if the theory were correct, would make them volcanoes within volcanoes—an explanation that seems unlikely at best.

Darwin’s notion, still the most widely accepted view, was that there is an association between atolls and volcanic islands, but that atolls begin life not on the rims of extinct craters but in the shallow waters of an island’s shores. Like many of Darwin’s ideas, his theory of coral atoll formation had the virtue of explaining not just how atolls are formed but how that process is linked to other kinds of coral formations, thus neatly accounting for all instances of what is essentially the same thing. He recognized that fringing reefs (on the shores of islands), barrier reefs (surrounding islands at some distance from the shore), and atolls (rings of coral without any island at all) are, in fact, a series of stages. The key to connecting them was the concept of subsidence—the idea that an island gradually sinks while the coral encircling it continues to grow. Thus, in the course of time, a fringing reef would become a barrier reef, and a barrier reef would eventually become an atoll.

AN ATOLL IS a very natural habitat for anything that swims or flies through the air. Atolls are home to more than a quarter of the world’s marine fish species, a mind-boggling array of angelfish, clown fish, batfish, parrotfish, snappers, puffers, emperors, jacks, rays, wrasses, barracudas, and sharks. And that’s without even mentioning all the other sea creatures—the turtles, lobsters, porpoises, squid, snails, clams, crabs, urchins, oysters, and the whole exotic understory of the corals themselves. Atolls are also an obvious haven for birds, both those that range over the ocean by day and return to the islands at night and those that migrate thousands of miles, summering in places like Alaska and wintering over in the tropics.

For terrestrial life, however, it is quite a different matter. A typical atoll in the Tuamotus might support thirty indigenous species of plants and trees—as compared with the more than four hundred native plant species that might be found on a high island like Tahiti, or the many thousands that grow on a large continental island like New Zealand—and, among land animals, only lizards and crabs. While there are places on an atoll where one might, for a moment, imagine oneself to be surrounded by land—places where one’s line of sight is blocked by trees or shrubs—a few minutes’ walk in any direction will quickly dispel the illusion. Strolling the length of even a largish motu, you eventually come to a place where you can see water on both sides. At such moments it becomes breathtakingly clear that the ground beneath your feet is not really land in the way that most people understand it, but rather the tip of an undersea world that has temporarily emerged from the ocean. The real action, the real landscape, is all of water: the great rollers that boom and crash on the reef, the rush and suck of the tide through the passes, the breathtaking hues of the lagoon.

And yet, when Europeans first reached the Pacific, they found virtually all the larger atolls inhabited. Even those that were clearly too small to support a permanent population often showed signs of human activity. On one tiny, uninhabited atoll, an early explorer found an abandoned canoe and piles of coconuts at the foot of a tree; on another there was the puzzling presence of unaccompanied dogs. Even the pit in which the Dutch sailors found water had almost certainly been dug by someone else. What all this appeared to suggest was that even the most insignificant and isolated specks of land were being visited by people who could come and go.

There are not many good early descriptions of these people. The Tuamotus offered almost none of the things that European sailors needed—namely, food, water, and safe ports—and their complex network of reefs was dangerous to ships. With so little to be gained and so much to be lost, Europeans tended not to linger, and the early eyewitness reports are correspondingly slight. What they did manage to observe about the inhabitants of the Tuamotus was this: they were tall and well proportioned (Quirós referred to them as “corpulent,” presumably meaning something like “robust”); their hair, which they wore long and loose, was black; their skin was brown or reddish and, according to the Dutch explorer Le Maire, “all over pictured with snakes and dragons, and such like reptiles,” an unusually vivid description of tattooing. Europeans, it is worth noting, had a famously difficult time identifying the color of Polynesian skin; a later Dutch navigator would describe the inhabitants of Easter Island as pale yellow where they were not painted a dark blue.

For food, the inhabitants of the low islands had coconuts, fish, shellfish, and other sea creatures; for animals, it is clear that at least they had dogs. Their knives, tools, and necklaces were made of shell (later investigators would also discover basalt adzes, which could only have been transported from a high island, there being no local sources of volcanic rock). Their principal weapons were spears, with which they armed themselves at the approach of strangers. Many Europeans who sailed past these islands reported seeing the inhabitants standing or running along the beach with their weapons in hand. Some interpreted their shouts and gestures as an invitation to land, others as an exhortation to depart, but, as “both sides were in the dark as to each other’s mind,” it was difficult to know for sure.

Later observers would describe the “roving migratory habits” of these atoll dwellers, noting that they wandered from place to place, “so that at times an island will appear to be thickly peopled, and at others scarcely an individual is to be found.” Census taking proved almost impossible, because some portion of the population was always “away,” hunting turtles or collecting birds’ eggs or gathering coconuts or visiting in some other corner of the archipelago. All of which raises an interesting question: Since there are almost no trees on an atoll, and certainly none of the larger species that in other parts of the Pacific provided wood for keels and planks and masts, what did the inhabitants of the low islands do for canoes? It being inconceivable that they could ever have lived in this watery world without them.

We have an early description, from 1606, of a fleet of canoes that came out “from within the island,” meaning presumably from across the lagoon, on the Tuamotuan atoll of Anaa. The vessels were described as something like a half galley—that is, a boat with both oars and masts—and were fitted with sails made of some kind of matting. Most had room for fourteen or fifteen men, though the largest carried as many as twenty-six. They were made, wrote the observer somewhat enigmatically, “not of one tree-trunk, but very subtly contrived.”

There is a picture in A. C. Haddon and James Hornell’s Canoes of Oceania that sheds some light on this remark. It shows a small canoe from the island of Nukutavake, in the southern Tuamotus, which was brought to England in the 1760s by Captain Samuel Wallis. Now held in the British Museum, it is described as “by far the oldest complete hull of a Polynesian canoe in existence.” At just twelve feet long, it is not nearly big enough to carry fourteen or fifteen men and was probably a small fishing boat, to judge by the burn marks on its upper edge, which are thought to have been made by the friction of a running line.

The amazing thing about the Nukutavake canoe is the way it’s constructed. It is composed of no fewer than forty-five irregularly shaped pieces of wood ingeniously stitched together with braided sennit, a kind of cordage made from the inner husk of a coconut. Close up, it looks like nothing so much as a crazy quilt whose seams have been decoratively overstitched with yarn. It is difficult to believe that such neat and painstaking rows of sewing could be made with something as rough as rope; or that what they are holding together could be something as stiff as wooden planks; or that anyone would think of making something as solid and important as a boat using such a method. Everything about it suggests cleverness and thrift and also, plainly, necessity. You can even see where the boards have been patched with little plugs or circles of timber held in place with stitches radiating out like the rays of a sun, and at least one plank shows signs of having been repurposed from another vessel.