Полная версия

Collins New Naturalist Library

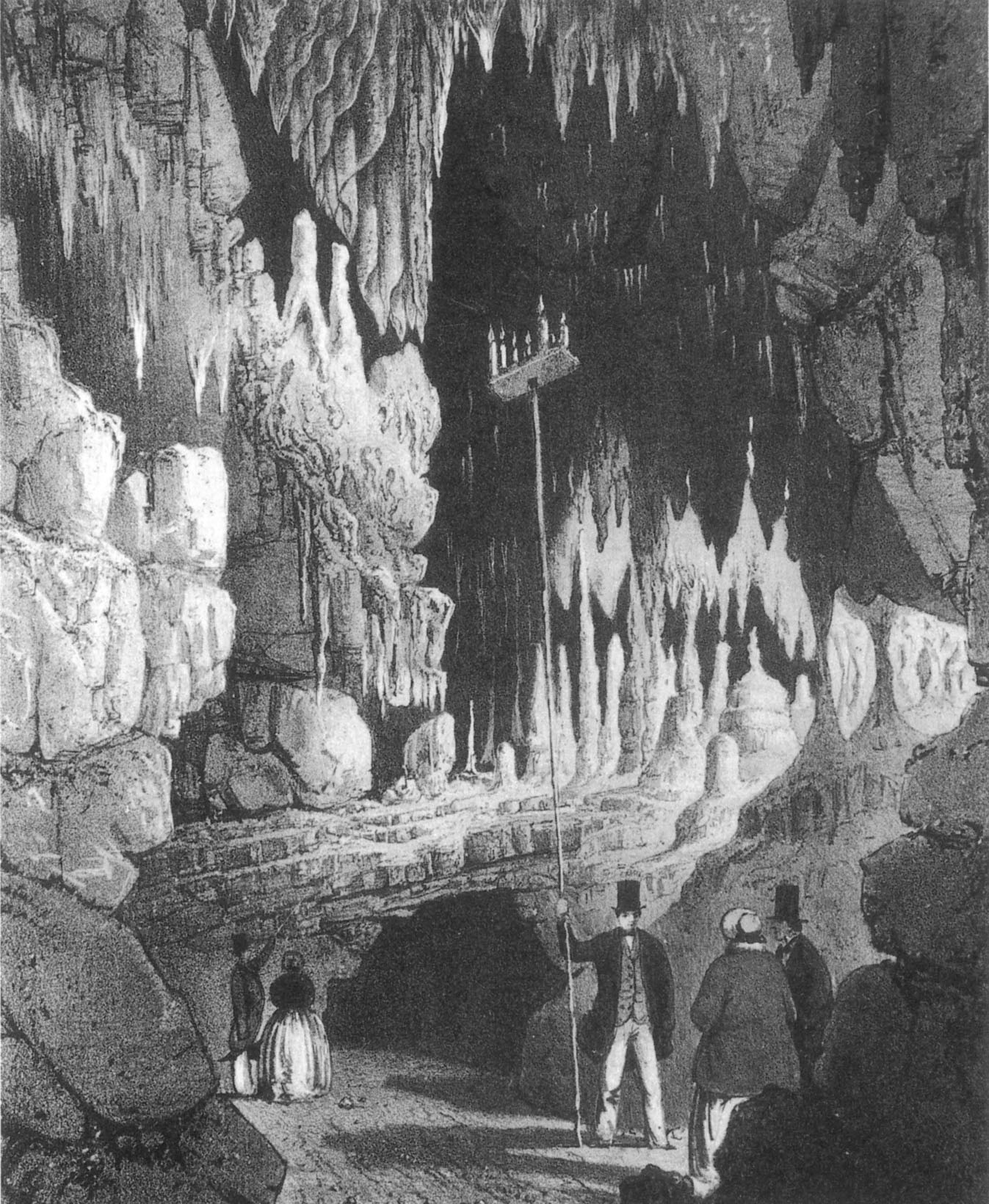

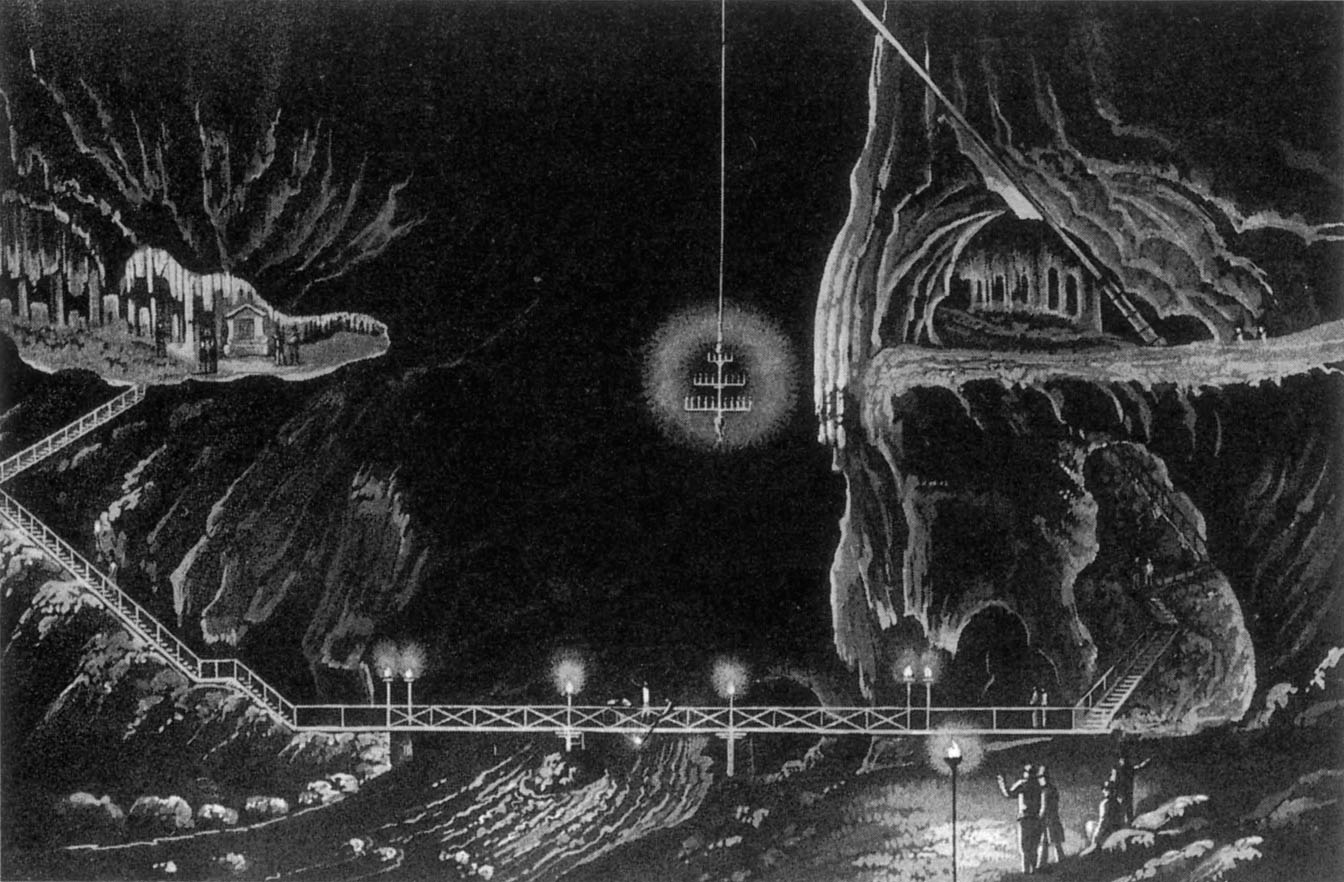

Fig. 1.5 Interior Chamber of Cox’s Stalactite Cavern, Cheddar, Somersetshire. Lithograph by Newman & Co. London; pub. S. Cox, Cheddar about 1850. (Courtesy of Trevor Shaw)

“I fastened a cord about me, and ordered them to let me down gently. But being down about two fathom I found the rocks to bear away, so that I could touch nothing to guide myself by, and the rope began to turn round very fast, whereupon I ordered the miners to let me down as quick as they could.”

He landed dizzy but safe 21 m below, on the floor of a cavern 35 m in diameter and nearly 37 m high within which he found large veins of lead ore. Surprisingly, Beaumont’s account failed to stimulate much curiosity about caves in scientific circles, and after a brief flurry of lead mining, the cave, known as Lamb Leer, was abandoned; its entrance shaft eventually collapsed and the sealed-off chamber was virtually forgotten for two centuries.

The rediscovery of Beaumont’s long-lost Lamb Leer cave took place in 1879, the same year that a young French law student, Edouard-Alfred Martel, made his first visit to the famous Adelsberg Cave in Slovenia (which was then part of Austria, but since World War II has reverted to its local name of Postojna Jama). Martel was completely enthralled, and in 1883 began to devote all his vacation time to cave explorations in the Causses of southwestern France. What set him apart from previous cave explorers, was his meticulous preparations and his systematic recording of all aspects of the caves he explored, combined with a tremendous physical ability and courage. His speciality was deep vertical pits, and in 1889 he successfully negotiated the 213 m vertical entrance shaft of the Rabanel pothole north-west of Marseilles – an outstanding feat given the equipment then available.

To calculate a pit’s depth, he would read the barometric pressure at the bottom and compare it with the surface pressure. He measured the horizontal dimensions of each newly-discovered chamber with a metal tape, drawing a sketch of the cave as he worked. Roof heights were calculated with an ingenious contraption: after attaching a silk thread to a small paper balloon, he would suspend an alcohol-soaked sponge beneath it, light the sponge, and measure off the length of thread carried aloft by the miniature hot-air balloon. Martel also habitually recorded subterranean air and water temperatures, finding variations with depth and season, and amassed whole volumes about cave geology, hydrology, meteorology and flora and fauna. But perhaps his greatest contribution to cave science was his research on how subterranean water circulates – a study prompted by his own bout with ptomaine poisoning, contracted from drinking spring water in 1891. After recovering from the illness, he traced the spring’s source using fluorescein dye introduced to nearby sink holes. Descending the appropriate pit, he found the putrefying carcass of a dead calf that had contaminated the spring with what he wryly termed “veal bouillon”. Further study allowed him to distinguish between “true springs”, fed by diffuse circulation of rainwater, cleaned and filtered by its passage through soil and rocks, and “false springs” fed by a rapid flow from sinkholes via cave passages too large to filter out impurities. Martel’s subsequent campaigning for stricter control of sources of drinking water eventually led to a dramatic reduction in deaths from typhoid and won him a gold medal from the French Government.

In 1895 Martel founded the French ‘Société de Spéléologie’, arguing that ‘speleology’, which had been previously considered a sport or a singular eccentricity, should be recognized as a fully-fledged science – “a subdivision of physical geography, like limnology for lakes and oceanography for seas.” A prolific author, he edited Spelunca, his Society’s bulletin, and wrote books about his own cave discoveries. In 1907 the French Academy of Sciences awarded him the grand prize for physical sciences, and in 1928 he was elected president of the Geographical Society of Paris. By the time he died in 1938, aged 78, the grand old man of speleology had personally probed nearly 1500 caves, hundreds of which had never been entered before; his technical innovations had become standard equipment for other cavers; and above all, his persistence and dedication had created a framework within which the seedling science of speleology could develop and blossom.

Meanwhile, the systematic documentation of caves had also started in Britain, with the formation of the Yorkshire Ramblers’ Club in 1892. Under the influence of S.W. Cuttriss, dubbed ‘the scientist’ for his assiduity in recording the group’s findings, its members drew up surveys of the caves they explored, and kept notes of temperatures, altitudes and geographical features.

The great exploration challenge of the day was the awesome Gaping Gill, a pothole high on the slopes of Ingleborough Hill which had been plumbed to a depth of 110 m, but had never been descended. The main obstacle to its exploration came from Fell Beck, an icy stream which cascades down the entrance, filling it with spray and extinguishing any flame which might light a caver’s descent, as well as half-drowning him. A local man, John Birkbeck, had made two heroic, but unsuccessful attempts to descend the pit in the 1840s, after digging a trench to divert the Fell Beck to another sink. His first try nearly proved fatal, when strands of his rope were severed on a rock ledge, but on his second attempt he reached a ledge at 58 m which now bears his name. Yorkshire Ramblers’ member Edward Calvert took up the challenge and had almost completed his own preparations for a descent on rope ladders in 1895, when Martel arrived on the scene, hot-foot from London where he had been invited to address an International Geographical Congress on cave-hunting methods.

As something of a celebrity, Martel was encouraged by the lord of Ingleborough Manor to have a crack at the great pothole and given the support needed to refurbish and extend Birkbeck’s trench. On August 1, before an eager crowd, Martel knotted together his lengths of ladder and lowered them into the darkness. As he climbed down the four metre-wide shaft he was rapidly enveloped by “half-suffocating whirls of air and water” which soaked his clothes and the field telephone which he relied upon to communicate instructions to the back-up team who controlled his safety line from the surface. The cascade redoubled 40 m down and he had to descend through a “frigid torrent gushing from a large fissure”. Pausing on Birkbeck’s ledge to untangle the huge heap of rope which had lodged there, he continued into the unknown depths below. Sixteen metres on, the walls of the shaft suddenly receded and Martel found himself swinging like a pendulum near the roof of an immense chamber nearly 160 m long by 30 m high. He alighted on the floor only 23 minutes after he began the descent, and characteristically at once set about measuring and sketching his discovery. For an hour and a quarter, the Frenchman revelled in the spectacle of the “Hall of the Winds”, Britain’s largest underground chamber from whose roof the waters of the Fell Beck tumbled “in a great nimbus of vapour and light”. There was a certain sense of nationalist triumph too: “The most pleasant feature was the thought that I had succeeded where the English had failed, and on their own ground.”

Fig. 1.6 Gaping Gill – the main chamber showing the waterfall falling 110 metres from the surface. A photograph taken in the 1930s by Eli Simpson. (Trevor Shaw collection)

Martel’s descent of Gaping Gill received wide publicity and awakened an interest in the possibilities of cave exploration in other parts of Britain. A group of Derbyshire rock climbers calling themselves the Kyndwr Club started to explore the caves of that county and further afield. One of their leading spirits was Dr E.A. Baker, a native of Somerset, but at that time resident in the Midlands. He was a colourful and influential character, an academic who later became director of the School of Librarianship in the University of London, but whose interest in caving was primarily sporting.

At about this time, H.E. Balch, a young postal worker at Wells in Somerset, came across a fragment of reindeer antler in the Hyena Den near Wookey Hole and, inspired by the work of Professor (later Sir William) Boyd Dawkins, at once threw himself into a study of all kinds of archaeological and fossil cave sites on Mendip. Soon Balch had founded the Wells Natural History and Archaeological Society and started the collections which eventually grew into Wells Museum. The subsequent arrival on the Mendip scene in 1902 of Baker and his colleagues from Derbyshire led to a long and fruitful collaboration, during which many of Mendip’s greatest caves were dug open and explored. Both Balch and Baker were prolific writers and their publications, spread over several decades, played a large part in stimulating an interest in caving during the early part of this century. A number of clubs began to appear which cheerfully combined a scientific and sporting approach to caving, setting a pattern which has continued to the present day. Scientifically motivated ‘speleologists’ still recognize their dependence on sporting cavers for much of the initial exploration and often for support when working in the more exacting situations. Many are in any case themselves sporting cavers, or were in their younger days. On the other side very few of those whose motives are primarily sporting are completely uninterested in the whys and wherefores of the natural features which provide them with their sport. They also appreciate that scientific understanding increases the chances of finding more caves.

There are few completely unexplored places anywhere on the surface of the earth and none in a country such as Britain; but caves hold out the promise, or at least the hope, of completely new discovery. Most cavers must sometimes dream of one day discovering a new cave, or an extension to a known one, and of being the first to gaze upon whatever wonders it may hold. If these are the things which provide motivation for caving as a sport, they are nearly always reinforced by at least some measure of scientific curiosity, and most cavers combine the two in varying proportions.

In the years after World War II, the popularity of caving, as of so many other active pursuits, increased enormously in many parts of the world. In Britain the 1950s and 60s in particular saw a great proliferation of caving clubs and, although some of these were ephemeral, the overall level of interest and activity has remained high. Perhaps the most important development in British caving in the early post-war years was the opening up of South Wales as a major caving region. Up until 1936, cavers had taken surprisingly little interest in the area considering that Porth-yr-Ogof had been known for hundreds of years and Dan-yr-Ogof had been discovered and explored as far as the waterfalls in 1912. It was to these two caves that experienced cavers from Yorkshire and Mendip first turned their attention in 1936 and interest in the area developed rapidly. By the time that caving came to a virtual halt with the outbreak of war in 1939, the potential of South Wales was apparent to all. In 1946 the South Wales Caving Club was formed and within a few months two of its members, Peter Harvey and Ian Nixon, dug their way into the lower end of the great Ogof Ffynnon Ddu cave system on the east side of the Upper Tawe Valley. Initially rapid exploration was halted by a series of sumps (flooded sections of passage) and it was not until 1966 that a dig in the upper levels of the cave gave access into the vast maze of OFD II. A rush of new discoveries followed in quick succession over the next year, extending the vertical range of the cave to 300 m and its total length to around 40 km, making it Britain’s deepest and longest cave system. (Although cave divers have since linked up various parts of the Ease Gill system in Yorkshire to give it the number one position with an overall passage length of over 70 km).

As we have seen, cave science, and in particular the archaeological and palaeontological investigation of caves, started well before the development of caving as a sport. As early as the mid-nineteenth century the living faunas of caves were receiving fairly extensive study in mainland Europe and America by the likes of J.C. Schiodte and A.S. Packard; and following the influence of Martel, the physical aspects of speleology – geology, geomorphology and hydrology – were well established there by the turn of the century.

Underground naturalists

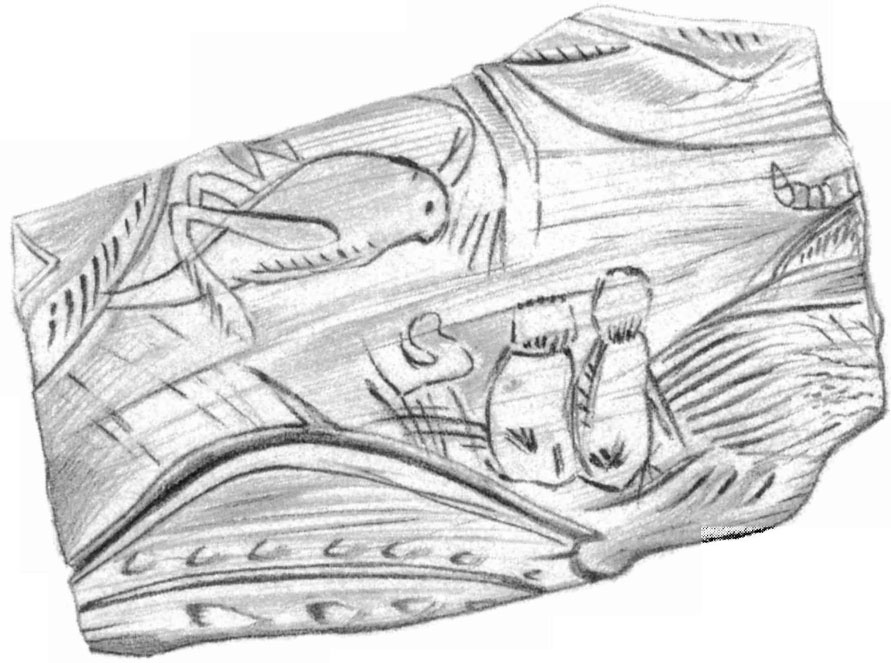

Evidence that early man was conscious of the existence of a subterranean fauna dates back to a remarkable engraving of a cave cricket on a bison bone discovered by Count Begouen while excavating in the Grotte des Trois Frères in the French Pyrenees. The carving is believed to be 18,000 years old, yet is sufficiently clear and detailed for the subject to be recognizeable as a Troglophilus species, which today is distributed from Italy to Asia Minor, but no longer inhabits France.

For the next surviving reference to cave life in Europe, we must move on to the 16th century and the observant Count Trissino, who, in a letter dated 5th March 1537, recorded what must have been a form of the cave-limited amphipod, Niphargus. He noted that at the far end of the Covolo di Costozza in northern Italy there was a deep pool of clear water. “In this water no fish of any kind are found, except for some tiny shrimp-like creatures similar to the marine shrimps that are sold in Venice.”

Fig. 1.7 A prehistoric engraving on a bison bone, discovered by Count Bégouen in the Grotte des Trois Frères (French Pyrenees), featuring the cave cricket Troglophilus. (After Bégouen)

The Slovenian Olm, Proteus, seems to have been well-known to the villagers of the Trieste area for centuries. Specimens occasionally appeared after floods in the Lintverm (from the German ‘Lindvurm’, meaning ‘dragon’) – a tributary of the River Bela near Vrihnika. With their long, pink, rather reptilian bodies, they were taken, not unreasonably, to be dragon fry – the offspring of a shadowy monster who lived in the roaring cave from which the river flowed and who caused periodic floods by opening sluice gates when her living quarters were threatened by rising water. But in the 1680s, Baron Johann Valvasor, a Slovene nobleman and well-travelled amateur scientist, ruined centuries of colourful legend by exposing the Olm as a perfectly natural blind cave salamander.

In 1799, the German naturalist-explorer Baron Alexander von Humboldt, accompanied by a French botanist called Bonpland, visited the famous Cueva del Guacharo in the Caripe Valley of Venezuela. There he collected and described a cavernicolous bird, Steatornis caripensis, belonging to the order which includes the nightjars, which had been known for a long time to the Indians under the name ‘guacharo’. Humboldt was greatly impressed by the screeches produced by the birds when disturbed at their cave roost. “Their shrill and piercing cries strike upon the rocky vaults,” he wrote, “and are repeated by the subterranean echoes.” Having heard them myself, I would describe the racket as the sound of a thousand mad chickens locked up in a barn with a fox.

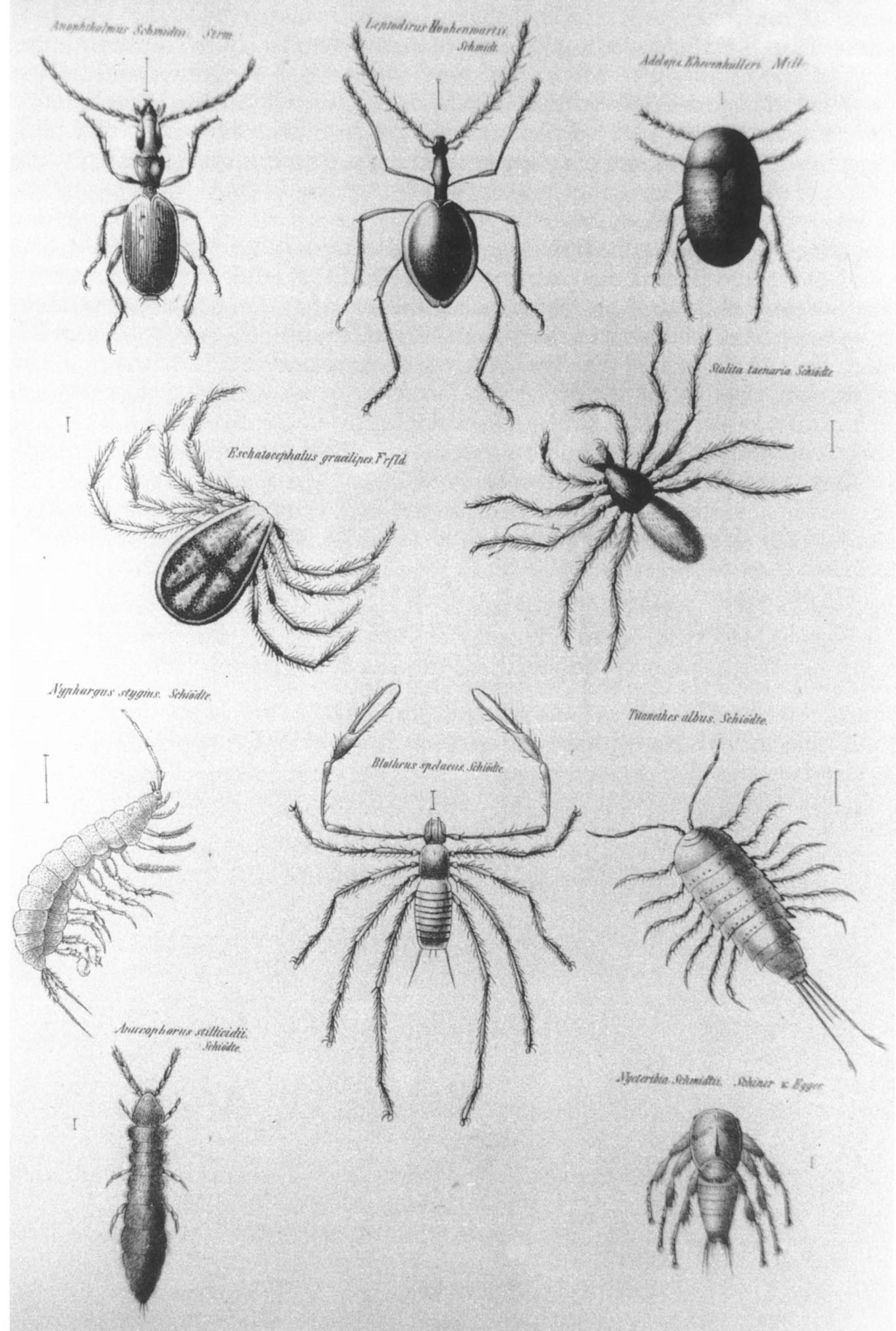

In 1808, Schreibers discovered the first invertebrate cave fauna in Austria and more extensive collecting was done in the Postojna area by Count Franz von Hohenwart and others from 1831 onwards. It was there too that the Danish zoologist J.C. Schiodte recognized that cave faunas showed differing degrees of specialization to life in darkness, and so laid the foundations for a system of ecological classification of cave life. This was advanced in a more rigorous form in 1854 by J.R. Schiner and has been widely used by cave biologists ever since. This work perhaps marked the beginnings of the systematic discipline of ‘biospȼologie’, a term proposed by Armand Viré in 1904, to refer to the study of subterranean life.

Fig. 1.8 The old route across the underground river Pivka in the Great Hall of Postojna Jama in Slovenia from an aquatint engraved by G. Dobler after a painting by Alois Schaffenrath, published in 1830. (Courtesy of Trevor Shaw)

In the USA important work continued intermittently from 1840. In that year Davidson collected the first specimens of a blind white fish in Mammoth Cave, described by de Kay, Wyman and Tellkampf as Amblyopsis spelaea. Tellkampf went on to describe other fauna from Mammoth Cave and was followed by E.D. Cope and A.S. Packard, whose remarkable studies through the 1870s put America for a time at the forefront of biospeleological research. Meanwhile, in the 1840s, V. Motschoulsky reported the first cave-specialized insects captured in the caves of Caucasia, and in 1857 De la Rouzee discovered the first cavernicolous insects known from France.

Scientific investigation of our cave faunas began in a round-about way in about 1852, when Professor Westwood and S. Bate included the following reference in their History of the British Sessile-eyed Crustacea, Vol.1, published in 1863.

“In the year 1852”, writes Bate, “Professor Westwood was so fortunate as to obtain from a pump-well near Maidenhead, a quantity of [Niphargus sp.] … since when they have been found in Hampshire, Wiltshire … and very recently in Dublin.”

Shortly afterwards, news of the discovery in Europe and America of strange blind cave animals prompted Naturalists E. Percival Wright and A.H. Haliday to search for similar creatures in Mitchelstown New Cave in Co. Tipperary. Their search was successful and they described their find – a tiny Collembolan doubtfully identified as Lipura stillicidii Schiodte – in a paper read before a British Association Meeting in Dublin in 1857.

More than thirty years were to elapse before the next glimmer of enthusiasm for Irish cave life manifested itself in the form of a joint excursion in 1894 by the Dublin, Cork and Limerick Field Clubs to the Cave of Mitchelstown. One of the participants, George H. Carpenter, recorded that “after an informal luncheon on the roadside, the party being provided with candles, descended the sloping passage and ladder which led to the depths below.” They spent two hours searching for cave animals and, although they failed to reach the underground river, made a reasonable collection of fauna, including the rare blind cave spider now known as Porrhomma rosenhaueri. In the same year, pioneering English arachnologist F.O.P. Cambridge collected spiders in Wookey Hole, but without finding anything of particular interest.

Early in 1895 E.A. Martel and his wife paid a well-publicised visit to Ireland. The event prompted the Fauna and Flora Committee of the Royal Irish Academy to support H.L. Jameson with a grant “to further investigate cave fauna in Ireland”. He joined the Martels in the Enniskillen area of Co. Fermanagh and, while the Frenchman surveyed the caves and drew up his plans, Jameson collected cave animals. The interest seems to have persisted, for Jameson is also known to have made faunal collections in Speedwell Mine in Derbyshire in 1901, but there then followed a gap of over thirty years during which British cave fauna was again neglected.

Fig. 1.9 One of the earliest illustrations of cave fauna from Adolf Schmidl’s Die Grotten und Höhlen von Adelsberg, Lueg, Planina und Laas. Wien, Braumüller, 1854. (Courtesy Trevor Shaw)

In 1936 the British Speleological Association was launched, with a brief to co-ordinate the work of caving clubs and to foster interest in the scientific aspects of caving. Things did not run entirely smoothly, however, and in 1947 another body, the Cave Research Group of Great Britain, emerged with a more specific research interest. Both societies ran in parallel until 1973 when they merged to form the British Cave Research Association which has become a major publisher of speleological research.

Meanwhile another organization concerned with cave science had been formed in 1962. This was the Association of the Pengelly Cave Research Centre, now the William Pengelly Cave Studies Trust. It is London-based, but its interests are very much centred in Devon where it runs the Pengelly Cave Research Centre at Buckfastleigh. The trust is active in education and conservation and produces publications covering a broad range of speleological topics.

The multidisciplinary nature of speleology allows significant contributions to be made as much by talented amateur observers as by trained professional scientists, and we owe much of our present knowledge of the faunas of British caves to the work of a handful of exceptionally dedicated amateur naturalists. The central figures of the group were Brigadier E.A. (Aubrey) Glennie and his niece Mary Hazelton, who in 1938 began making systematic collections in the caves of Yorkshire, Derbyshire and Mendip. Glennie, an excellent all-round naturalist, picked up his interest in cave life while serving in India, where among other things, he published a study on the nesting behaviour of Himalayan Swiftlets in caves. On his retirement in 1946, he became a driving force in the biological work of the newly formed Cave Research Group, and was soon recognized as an authority on British hypogean amphipods. Hazelton assumed the mantle of Biological Recorder to the CRG, and for the next 29 years diligently co-ordinated the identification of collections submitted by fellow cavers and compiled the results for publication, first in the Transactions of the Cave Research Group and later of the British Cave Research Association. Among the most notable contributors to the faunal collections of this period were Jean Dixon of the Northern Cavern & Mine Research Society and W.G.R. Maxwell of Chelsea Speleological Society.

The 1950s saw the appearance on the scene of two particularly influential figures, both professional biologists. One was Dr Anne Mason-Williams, a microbiologist whose pioneering studies on the microflora of South Wales caves remains the definitive work in this field. The other was Dr G.T. ‘Jeff’ Jefferson, a lecturer in zoology at University College, Cardiff, who quickly established himself as the leading authority on British cave faunas and went on to become president of the British Cave Research Association, and a greatly respected ambassador for speleology in Britain. Jefferson’s major contribution to cave science in Britain before his untimely death in 1986, was in shaping the wealth of observation gathered by his amateur predecessors into a coherent picture of the biogeographical history and ecological relationships of our cave fauna. It is his work above all that has provided the inspiration for this book.

Non-cavers are fond of asking cavers why they venture underground. The usual answer is along the lines that “caving is good fun”. Many would add that caving is most fun when spiced with the excitement of discovery. For the sporting caver, this means finding a way into previously unvisited passages, or whole new cave systems. For the speleologist there is the further excitement of recording new observations and of gaining fresh insights into the history, development, or life of the cave. The discipline of cave biology remains poorly developed in Britain and Ireland, affording tremendous scope for discoveries of all sorts by amateur as well as professional naturalists.

Driving curiosity and a sense of wonder are perhaps the two features which above all unite the caver and the naturalist. I hope that this book can make the passion of the one intelligible to the other, and so enhance the experience of both.