Полная версия

Collins New Naturalist Library

David Allardice Webb (1912–95), the doyen of modern Irish botanists, first published An Irish Flora in 1943 (now in its seventh revised edition 1996),124 a small and innocuous-looking volume but full of plant identification tips as well as notes on the habitats and distribution of all Irish species, written in the author’s characteristic taut style. Webb was an outstanding field botanist as well as a brilliant conversationalist.

John J. Moore was the doyen of the Irish school of plant sociologists following the vegetation description methods of Braun-Blanquet. He was also a champion of the conservation of Ireland’s vanishing peatlands, as well as an inspired field worker. Both Moore and Webb represented the finest scientific traditions of the two main cultural strands of Ireland.

Integrated ecological studies of a region are now generally de rigueur, making it difficult for the more traditional floras to survive. However, the past 18 years have seen the publication of The Flora of County Carlow (1979) by Booth (1897–1988) assisted by Scannell;125 Flora of Connemara and the Burren (1983) by Webb & Scannell;126 The Flora of Inner Dublin (1984) by Wyse-Jackson & Sheehy-Skeffington;127 Flora of Lough Neagh (1986) by Harron128 and Synnott’s slim but valuable volume County Louth Wildflowers (1970).129

One of the greatest polymath naturalists of this century was Frank Mitchell (1912–98). Equipped with a brilliant and creative mind, he was primarily a geologist who branched off into many different fields of natural history. The Chair of Quaternary Studies in Trinity College was especially created to both honour him and capture his talents for the University. His early work on the vegetation history of Ireland was inspired by the Dane Knud Jessen, whom he assisted on Jessen’s first Irish visit in 1934. Mitchell’s many talents culminated in his remarkable book The Irish Landscape (1986)130 which was recently republished for the third time as Reading the Irish Landscape (1997)22 with the archaeologist Michael Ryan as co-author. The critic and writer Eileen Battersby summed up the book as ‘an extraordinary achievement in that this essentially geologically-based text offers a multifaceted and complete view of Ireland. It is a feat no other single narrative has matched.’131

Birds of Ireland maintained the high standard set by its predecessor of 1900 and drew upon the combined experience of the four best field ornithologists of the time.

The past 25 years have witnessed a remarkable upsurge in both professional and amateur natural history activity in Ireland. The literature generated by this new generation of naturalists has become increasingly sophisticated, and natural historians, once objects of some curiosity and derision, have at last achieved their just recognition in a rapidly evolving Irish society.13,20,51,123,126,132–142

2

Biological History

Approximately two million years ago, severe cold conditions developed in northwestern Europe marking the onset of the Pleistocene or Ice Age. At the height of this period, ice sheets smothered Ireland and much of the European Continent, eliminating plants and animals that had evolved throughout the preceding era. When the ice relented it gave way to alternating cycles of warmth and cold spread over the last 750,000 years. The effects were profound. The development of flora and fauna was periodically encouraged only to be inhibited and largely eliminated later, with the result that the plants and animals found in Ireland today are the outcome of a most complex and not fully understood sequence of survival and migration, driven by the climatic oscillations of the Pleistocene.

It was only some 13,000 years ago, at the close of the Ice Age, that the cold began to lift, allowing a progressive development of vegetation and fauna which has continued through to the present day. The activities of the Neolithic farmers commencing some 6,000 years ago inaugurated the first anthropogenic modifications of Ireland’s biotic inheritance. Woodland clearance, initiated by those farmers, brought about many long-term ecological changes including the elimination of some species, redistribution of others and the introduction of alien flora and fauna. This chapter will explore the history and sequencing of Ireland’s vegetational history while detailing what is known about the origins of Ireland’s mammalian fauna and, in particular, highlighting the history of red and sika deer and the wolf. The pedigree of the frog and natterjack toad in Ireland, subject to much speculation, will be explored, along with the history of Ireland’s freshwater fish. Finally the many unresolved questions concerning the origin of some Lusitanian or Mediterranean–Atlantic flora will be considered, as well as the curious geographical distribution of certain plant species, especially in parts of western Ireland.

The Pleistocene or Ice Age

The latter part of the Ice Age, from about 750,000 years ago, has been characterised by a series of alternating warm phases – known as ‘interstadial’ if minor and without the development of closed woodland and ‘interglacial’ when full woodland cover developed – followed by colder phases. The interglacials and interstadials are thought to have been relatively short, in the order of 10,000–15,000 years, with temperatures close to today’s levels which allowed a rich flora to emerge before it was expunged by the next cold phase. The vegetation which developed during these warm periods was generally similar to that found in other parts of Europe, although the record from Ireland is far from complete.1 The cold periods were longer in duration, lasting some 50,000–100,000 years, and ushered in arctic and tundra floras. During the most severe conditions the landscape was covered by ice in varying amounts making it difficult for living things to survive.

This chapter will follow the tentative chronological and stratigraphical sequence of the cold and warm stages of the Quaternary deposits over the past 500,000 years as proposed by Mitchell & Ryan.2

Years Ago Proposed tentative stratigraphical sequence 13,000–10,000 Late glacial 35,000–13,000 Midlandian (Drumlin) cold 65,000–35,000 Aghnadarraghian mild 79,000–65,000 Midlandian (Main) cold 122,000–100,000 Fenitian mild 132,000–122,000 Eemian warm 302,000–132,000 Munsterian cold 428,000–302,000 Gortian warm 500,000–480,000 Ballylinian warmPollen remains from interglacial deposits

The Ballylinian warm (500,000–480,000 years ago) takes its name from an area south of Castlecomer, Co. Kilkenny, where fossil pollen remains in a 25 m thick deposit of lacustrine clay show that the warm climate allowed the development of open forest containing most of the trees present in Ireland today including fir, spruce, hornbeam, oak, alder, wing-nut (found today in Turkey and present in Ireland from an earlier period) and yew. In the open areas there were grasses and heaths, where rhododendron and many herbs grew.3

The most famous interglacial deposit in Ireland is of peat and mud lying underneath glacial deposits cut by the Boleyneendorrish River near Gort, Co. Galway. It was first discovered and described by Kinahan in 1865 and was reexamined in 1949 by Jessen, Anderson & Farrington. They investigated the pollen remains in the muds and peat and named this warm interglacial stage the Gortian.4,5 The Gortian interglacial has been uncertainly dated as occurring some 428,000–302,000 years ago.2 About 12 other similarly aged deposits have been so far investigated in Ireland, some of whose results have been reviewed by Coxon, Mitchell & Ryan and Watts.1,2,6 The first plant species to appear at the onset of the Gortian interglacial phase, as summarised by Coxon, were the pioneering willow, juniper and buckthorn as well as many herbs and birch scrub. As the weather became milder the extent of pine and birch woodland grew while many other species – oak, elm, holly and hazel – are thought to have migrated into Ireland from other European ice-free areas. Unlike other interglacial sites examined in Britain, these Irish woodlands did not develop into a mature mixed oak forest but into heath, as increasing wet conditions fostered the growth of heather together with alder, yew, spruce and fir trees. The end result was a crowberry wet heath – to be replaced by tundra again when the Gortian period came to an abrupt end as temperatures plummeted. The next cold stage, the Munsterian, persisted from 302,000–132,000 years ago.

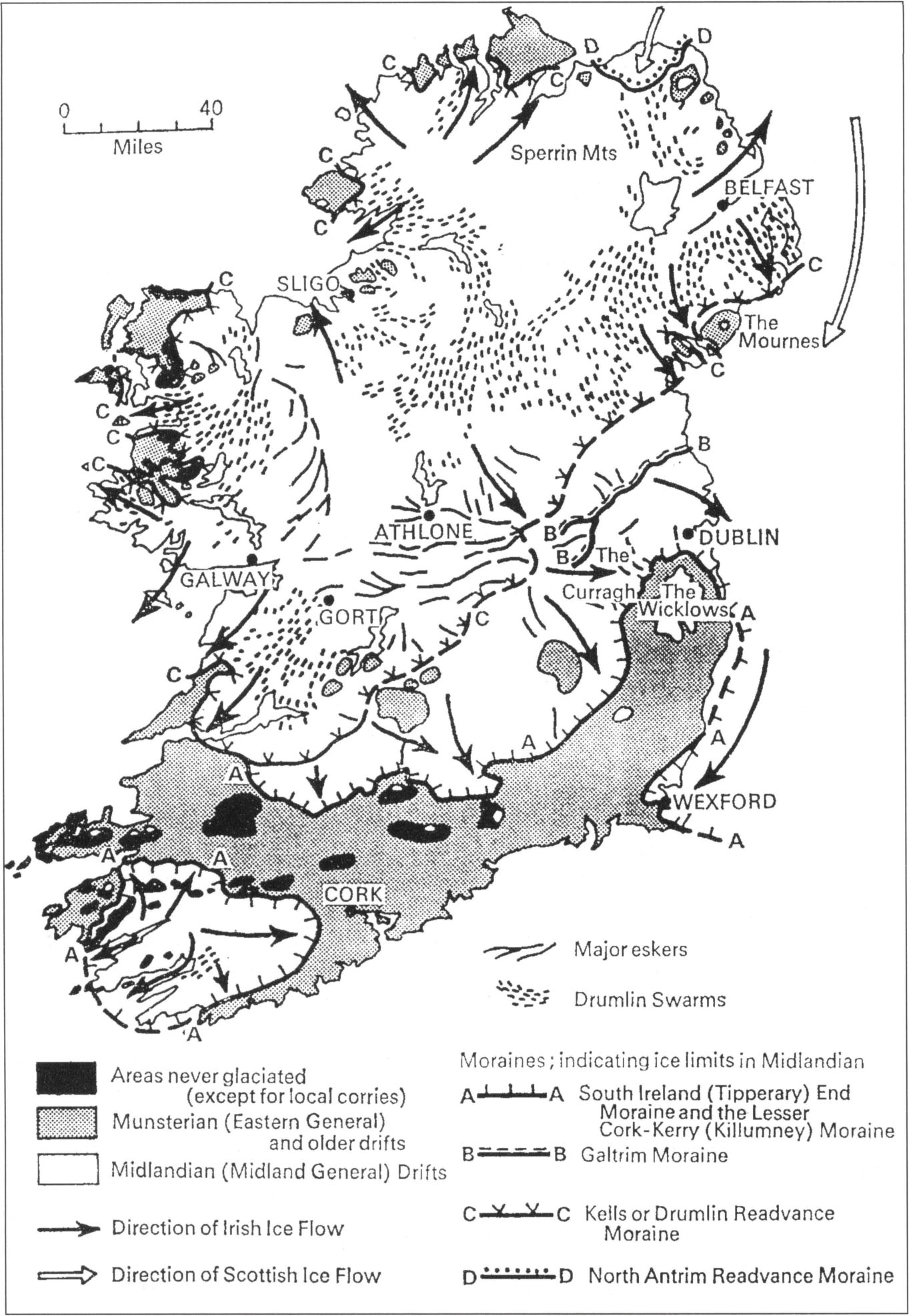

The Pliestocene geology of Ireland showing the areas considered never glaciated and the extent of the older Munsterian glaciation (302,000–132,000 years ago) and more recent two cold phases of the Midlandian: Main: 79,000–65,000 years ago and Midlandian Drumlin: 35,000–13,000 years ago. From J.B. Whittow (1974). Geology and Scenery of Ireland. Penguin Books, London.

The Gortian floral assemblage contains several species whose history in Ireland is a matter of much conjecture. The occurrence of pollen from Mackay’s heath, Dorset heath and St Dabeoc’s heath opens up the possibility of their survival through the subsequent cold phases rather than a more recent postglacial arrival on land bridges from their southern headquarters in Portugal, Spain and France. Rhododendron, another Gortian species, possibly moved into Ireland to escape declining temperatures elsewhere in Europe at the time but is generally considered to have become extinct in Ireland at the end of the Gortian phase. Its reintroduction came during the eighteenth century and it has since spread into many habitats, especially deciduous woodland and peatlands. Two further species, considered north American in their current distribution – the slender naiad and pipewort – were also present in Gortian deposits. They, like the heaths and heathers above, could possibly have continued their tenure in the country through the subsequent Munsterian cold stage in areas not subjected to intense coldness, having arrived before the glacial period by migration through Greenland and Iceland when the water barriers were not so great. This would make the need for other explanations unnecessary – such as their arrival on the feet of migratory waders and geese from western Greenland and northern Canada and perhaps America from the end of the late glacial period onwards.

Palaeobotanists have found it difficult to correlate the Gortian interglacial deposits with other such deposits in Britain and Europe but Mitchell & Ryan believe that the closest fit is with the Hoxonian period in Britain and the Holsteinian period in Germany. Whatever the correlation, the Gortian interglacial is considered by some scientists to have been the last warm interglacial before the onset of the very cold Munsterian stage.7 The Gortian period provided the opportunity for the development of some 100 taxa of higher plants of which some 20 are not native of Ireland today.

Before the Munsterian ice was fully in place, the low ground turned into a polar desert. Only the toughest species of the Gortian vegetation could have survived these conditions while others migrated southwards to avoid the falling temperatures. Jessen was of the opinion that many of the species that migrated southwards before the advancing cold in Europe ended up in the Black Sea area. During the Munsterian glacial period large masses of ice flowed into Ireland from the Scottish Highlands and probably covered much of Ireland during its maximum extent. Limited areas of high land in the west and south probably remained ice-free. Low-lying areas, even along the Atlantic coastline, were characterised by a cold polar desert climate. Only the hardiest forms of flora and flora could have survived in Ireland when the Munsterian cold stage was at its maximum extent.

Mitchell & Ryan have put forward some evidence for the occurrence of two warm or mild phases (the Eemian and Fenitian) which followed the Munsterian cold stage and lasted from approximately 132,000–100,000 years ago, but more research is needed to establish the full nature of these interludes before the onset of the next cold phase, the Midlandian (Main) cold stage. Around 79,000 years ago it became severely cold with arctic and dry conditions until ice sheets formed and spread out from their two main centres located in an area from Donegal to Belfast and in the Midlands. A tongue of Scottish ice also passed down the Irish Sea. There were also ice caps in the Wicklow Mountains and the Cork and Kerry mountains. There were, however, substantial areas south of a line approximately between Askeaton, Co. Limerick, and the Wicklow Mountains that remained ice-free, and it was in this very cold region that many plants and animals would have had the opportunity to survive to then recolonise Ireland with the onset of warmer conditions commencing some 13,000 years ago.

During the Aghnadarraghian period, approximately 65,000–35,000 years ago, mild conditions set in. Remains of fossil beetles indicate summer and winter temperatures similar to those of today. The relatively warm conditions encouraged the development of temperate cool woodlands with hazel and yew. The earliest mammalian remains in Ireland, molar teeth, tusks and broken bones of woolly mammoth and musk ox bones (but see below), were found in gravel deposited on top of a band of lignite (brown coal) and date from over 50,000 years ago. The warm Aghnadarraghian mild phase was brought to an end with the onset of dry cold conditions which persisted for some 8,000 years before the development of more ice marking the Drumlin phase of the Midlandian cold stage, but conditions were sufficiently mild to allow the development of open grasslands with scattered birch and willow woodlands. It was in this environment that many mammals flourished, evidence of their occupation provided by bone remains in caves. The renewed ice possibly peaked around 25,000 years ago and then lasted until about 15,000 years ago when it started to melt, a process that took about 2,000 years.

Grass covered eskers, sinuous ridges composed of glacial outwash gravel.

The late glacial period and the development of woodlands

By the end of the late glacial phase some 13,000 years ago the ice sheets had melted and the final ordering of the rocky skeleton and cosmetic adjustments to the skin of the Irish landscape were complete. Mountains, hills and rocks had been scraped, scoured and polished by the flowing ice. Soil and boulders had been lifted up, moved over huge distances and dumped as rude morainic material and glacial till: sinuous ridges of outwash gravels or eskers, some extending over several kilometres and reaching 20 m in height, had established their presence in the Midlands. Miniature hilly landscapes made of drumlins or small hilly lumps of glacial drift, possibly formed underneath the melting ice sheets or dropped as dollops of material, had appeared. Lake basins were scooped out, valleys were formed.

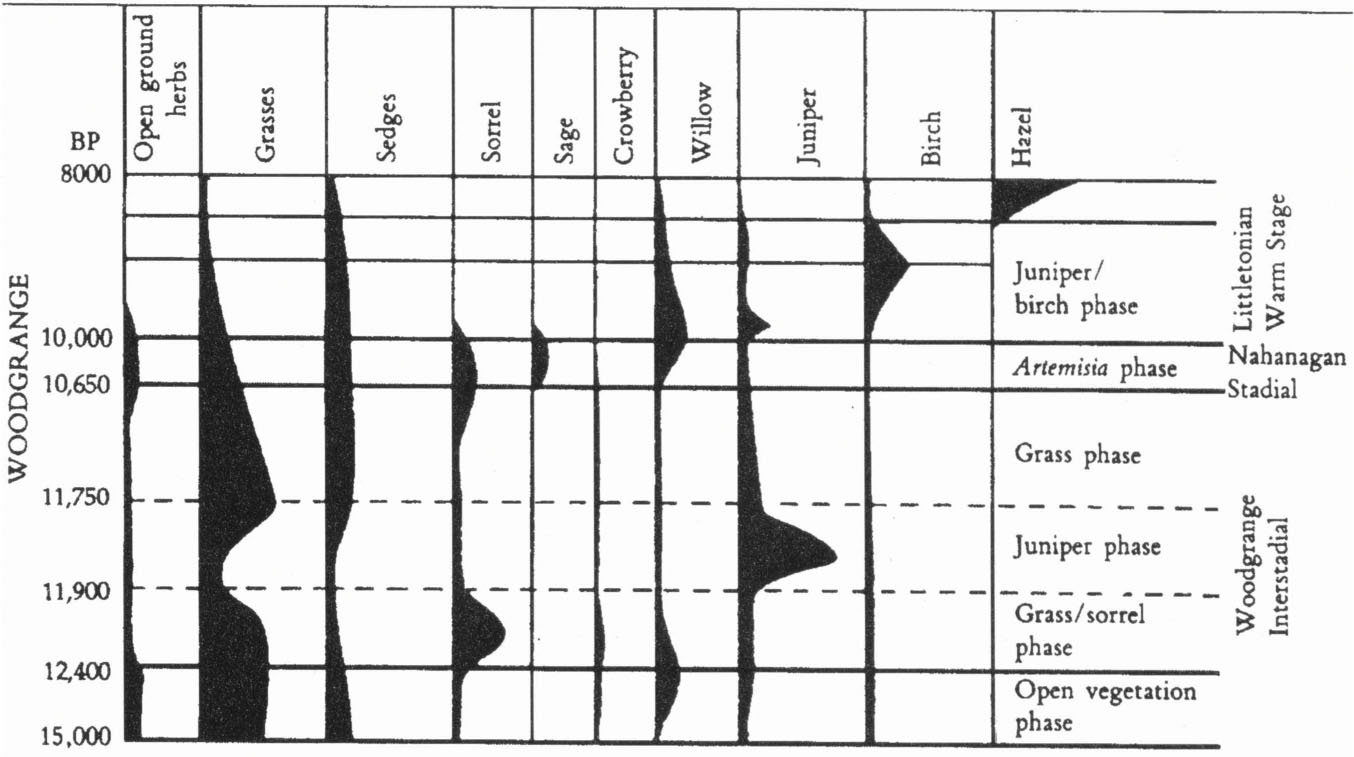

As it emerged from the cold, Ireland entered what is known as the Woodgrange interstadial phase; a sort of mini-interglacial period without the full development of woodlands. The name comes from the shallow lake basin lying between drumlins at Woodgrange, Co. Down, where pollen was blown, settled, and remained preserved in the organic muds. Originally described by Singh,8 the Woodgrange pollen signatures were later recounted by Mitchell & Ryan. They chronicle the succession of plants that settled and spread in this area over a period of 3,000 years.

The first plants to emerge and fix themselves in the bare soil were sorrels, grasses and the dwarf willow. This initial growth is known as the grass/sorrel phase. Five hundred years later juniper and birch flourished while other pollen deposits showed crowberry growing close to the Atlantic coastline near Roundstone, Co. Galway. In those days the Irish landscape must have approximated that of arctic tundra with a smattering of birch woodland and juniper scattered over the ground. However, this initial growth was brought to an abrupt end as a renewed drop in temperature killed off the pioneering species.

Pollen diagram from Woodgrange, Co. Down. From Singh8.

A cold snap, triggered by a southerly movement of arctic waters down the Atlantic coast of Europe around 10,600 years ago, suppressed the birch and juniper development and opened up bare patches of soil only suitable for the more resistant grasses. This period, lasting some 600 years, is named the Nahanagan stadial by Mitchell & Ryan, after Lough Nahanagan in the Wicklow Mountains where glacier ice reformed as it did in other mountain corries under the renewed influence of freezing temperatures. Such extreme conditions only allowed the emergence of a sporadic plant cover, mainly of arctic-alpine species, growing at low altitudes and also at sea level along the western seaboard – as shown by pollen remains from Achill Island, Co. Mayo, and Waterville and Killarney, Co. Kerry. There was permafrost on the lowlands with a scattered plant cover, much of it made up of dwarf willow and other arctic species. The initial vegetation cover of the Irish lowland landscape was a succession of different plant communities consisting of grasses, mugwort and low scrub with juniper and crowberry. Open grasslands later developed, characterised by docks and sedges. The mugwort, Artemisia sp. was also common, as evidenced by the pollen remains, thus giving rise to the description of this period as the Artemisia phase. These grasslands endured for some 1,000 years as large herbivores – giant deer and reindeer – stalked and munched their way through the lush pastures. The Nahanagan cold snap snuffed out much of the start of postglacial life in Ireland and the process had to commence all over again – from a generally bare soil to grasses to shrubs to dwarf trees and eventually to mature woodlands.

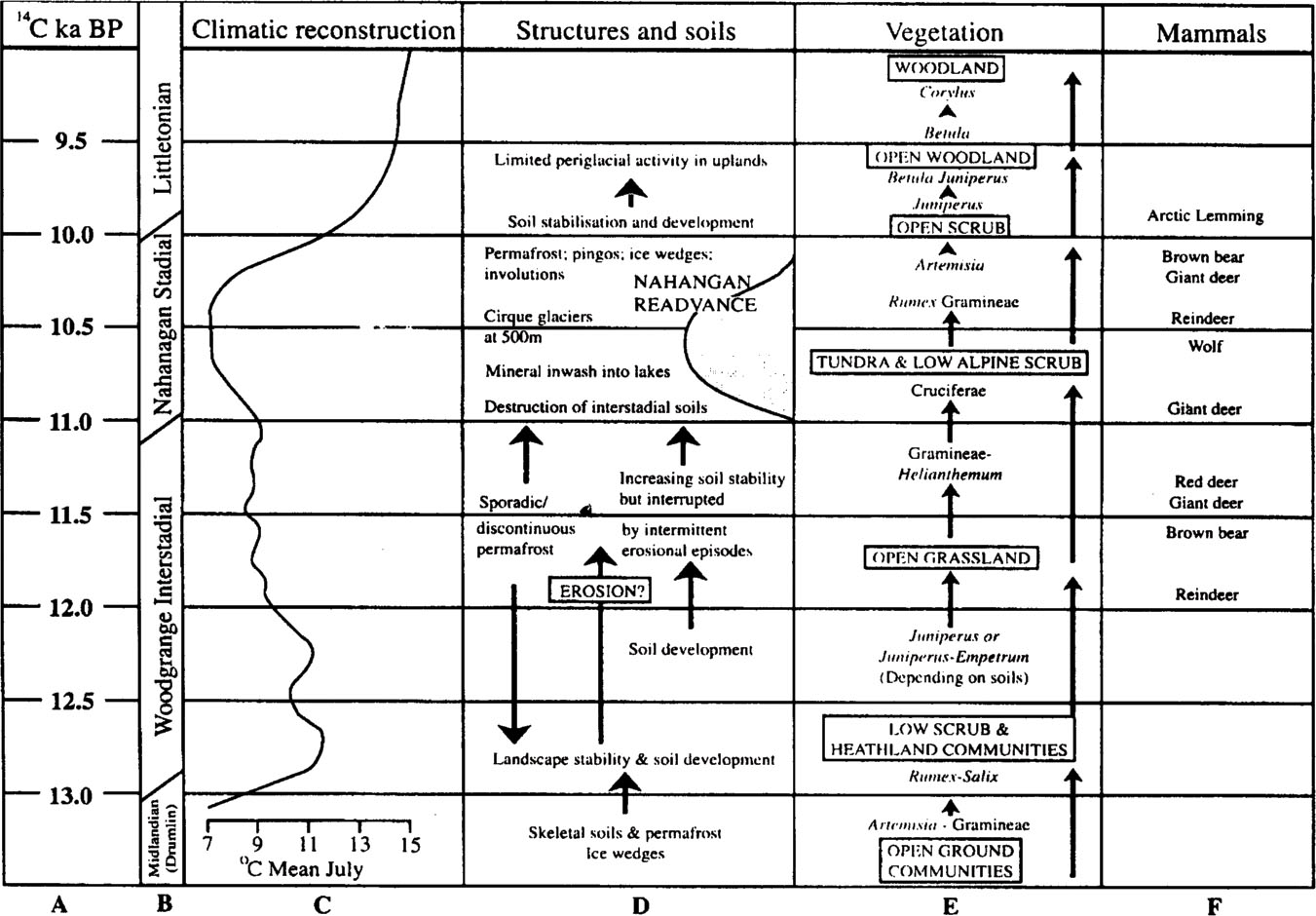

During the next 4,900 years, from 10,000–5,100 years ago, the Irish landscape evolved from open tundra to a country almost totally swaddled by woodlands. Only the mountains, poking above the green canopy, and the rivers, lakes and bogs in the lowlands differed from their surroundings. Temperatures continued to rise, more than doubling the July mean temperature from about 7°C to 15°C, approximately the same as today. Because of these new climatic conditions, Ireland became available for colonisation by the flora and fauna that had survived on the ice-free and warmer European mainland and also possibly in parts of Ireland.

How Ireland acquired its flora and fauna is a continuing and unresolved saga. There are three principal scenarios. Firstly, many plants and animals may have entered the country before the Ice Age or during interglacial periods and survived in ice-free areas. The flora and fauna then colonised the landscape at the end of the Ice Age. Forbes first championed this preglacial survival hypothesis in 1846.9 It received support from Praeger in 1932 and Beirne in 1952.10,11 Secondly, there may have been no Ice Age or interglacial survivors, and Ireland’s flora and fauna mostly arrived during the postglacial period, migrating from Britain and southern Europe when sea levels were some 130 m lower than present. This hypothesis was supported by Charlesworth in 1930, Godwin in 1975 and most recently by Mitchell & Ryan in 1997.2,12,13 Finally, postglacial arrival may have been by aerial dispersion, chance methods, and introduction, deliberate or accidental, by early man. This hypothesis was postulated by Reid in 1899 and more recently by Corbet in 1961.14,15

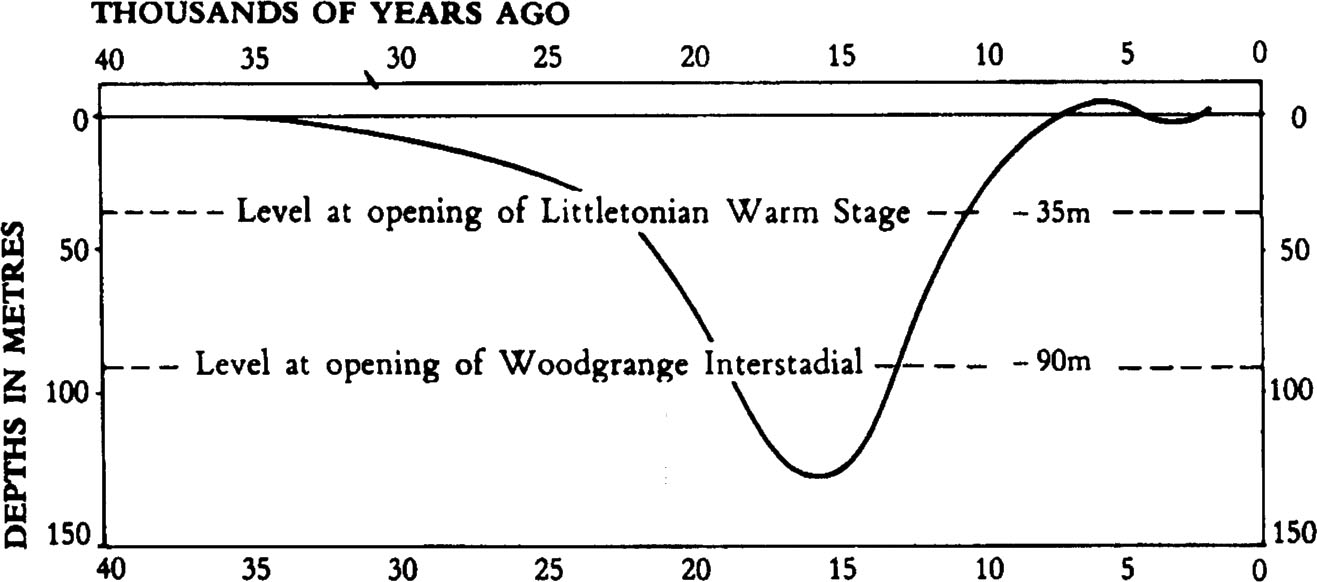

The most probable explanation is likely to be a combination of the three possibilities. Thus it would seem quite plausible for many species to have survived the Midlandian glaciation in the southern ice-free zones, and possibly earlier episodes of extreme coldness, while many other species may have arrived in Ireland during the postglacial period. The postglacial land bridge migration of flora and fauna has been strongly argued by Mitchell & Ryan. They postulated that land bridges between Ireland and Britain existed when the sea level fell to about 130 m below today’s levels exposing dry ridges of land, thus making it possible to cross dry-shod from the Lancashire-Cumbria area to Dublin, from north Wales to Co. Wicklow and from Cornwall to southeast Ireland. Ireland also had an Atlantic coastal ‘pathway’ linking it with southwest England, France and northern Spain. The sea fell to its lowest level some 15,000 years ago. By 10,000 years ago it was back to present day levels. Despite the appeal of the land bridge routes, the country could well have been repopulated from a reservoir of flora and fauna that had survived in the southern ice-free areas of Limerick, Cork and Waterford.

Late glacial Ireland. Column A gives the timescale for the last 13,000 radiocarbon years. Column B gives the names of the Irish type sites. Column C shows temperature trends, largely based on information from fossil animals and plants rather than instrumental measurements. Column D shows geomorphological and soil developments. Column E outlines vegetational developments. Column F lists mammalian records. From Mitchell & Ryan2.

In support of their land bridge concept, Mitchell & Ryan explain the process whereby the retreat northwards of the large wedge of ice that filled the area now occupied by the Irish Sea created a land bridge which was ‘pulled’ northwards with the withdrawal of the glacier. It is argued that the great weight of the ice depressed the land underneath which was squeezed out laterally and at the front of the glacier. Pushing down a fist into a ball of dough would produce a similar effect with the dough squeezed out laterally and rising up around the edges. The squeezed-out land moved out sideways and in front of the ice as a sort of bow of land as the ice pushed southwards. On the retreat of the ice northwards up the Irish Sea area the forebulge of land also retreated. Mitchell & Ryan, drawing upon a detailed study by Wingfield of the British Geological Survey,16 postulated that the fore-bulge moved or was pushed into the south end of the Irish Sea area about 11,000 years ago, when it provided a land bridge link between Devon and Carnsore Point, Co. Wexford. As the glacier melted and retreated northwards up the Irish Sea so the fore-bulge followed, providing a sort of moving land bridge link, of a continually diminishing height, across which plants and animals were able to migrate into Ireland from west Wales. About 9,500 years ago the bridge was enveloped and submerged by the rising waters of the Irish Sea.

Outline curve to indicate possible course of sea level around Ireland during the last 40,000 years. From Mitchell & Ryan2.

A land bridge also spanned what is now the English Channel, remaining open for business for approximately 2,500 years longer than the Irish-Welsh bridge. It was along this route that the plants and animals almost certainly moved from southern Europe to Ireland. They had about 1,500 years to travel across a ‘dry’ Irish Sea from Britain, having already trekked from the Continent into Britain over a ‘dry’ English Channel. It may seem a long time but in fact the colonisation process was a race against time as the immigration routes were being rapidly cut off by the rising waters, first in the Irish Sea and subsequently in the English Channel. Many species failing to cross the last bridge remained circumscribed to Britain, and the paucity of the Irish flora and fauna today is mainly – albeit not entirely – attributable to that late phenomenon. There remains, however, much conjecture and many difficult unanswered questions about the ways and means by which many animals and plants may have moved back into Ireland over the land bridges.17,18