Полная версия

Collins New Naturalist Library

Many of the plants and animals involved in the migration process would have travelled a distance of at least 1,000 km by direct line, say, for example, from Luxembourg to Dublin. The time allocated for the trip (about 2,500 years including the 1,500 years when the Irish land bridge was open) would have allowed a rate of migration of 400 m per annum, a not unrealistic rate of progress. The pace of settlement was fast indeed as oaks were already growing in the south of Ireland 9,000 years ago while wild boars were being hunted near Coleraine, Co. Derry, by the first men on record. Wild deer too, had already established their presence in the Midlands some 8,400 years ago. However, opponents of the land bridge hypothesis would argue that these species were already present in the country and their populations expanded their range with rising temperatures.

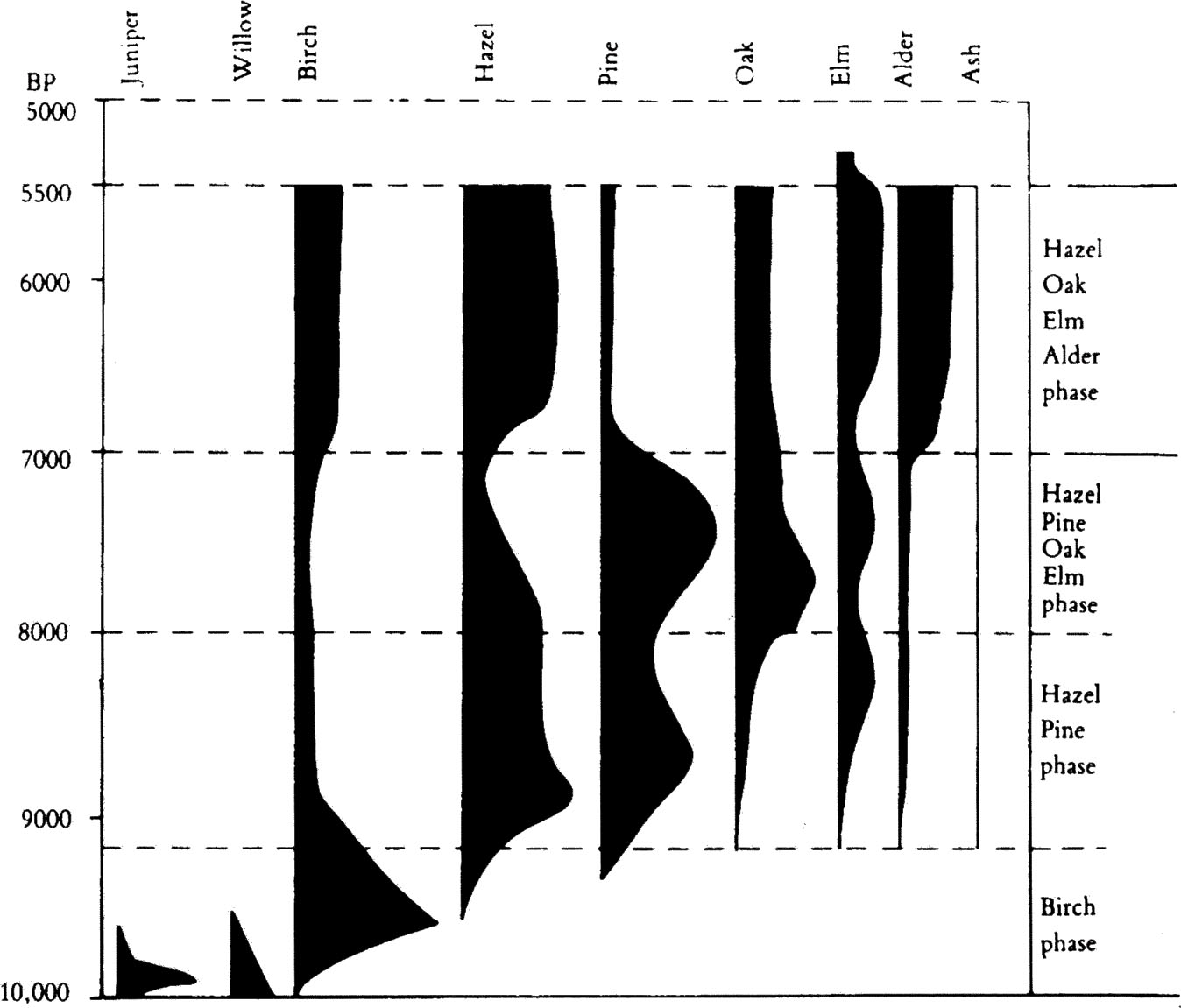

Ten thousand years ago, pollen deposits were being laid down in a raised bog near Littleton, Co. Tipperary, starting an important historical archive and providing one of the most important chronologies of vegetational development in Ireland from 10,000 years ago to the present time.19 It tells the story of rich meadows of grasses, docks and meadowsweet which were quickly replaced by a juniper scrub mixed with willow trees. These low-growing species were subsequently overtaken by the taller downy birch forming the first real woodlands. Hazel then established itself with a patchy distribution of sometimes quite dense stands, while Scots pine also started expanding from about 9,000–8,500 years ago to produce a pine-hazel wooded landscape.

The oak first put in an appearance around 9,000 years ago and quickly expanded its range together with the wych elm to form a high forest. As a result of this woodland expansion, the pine was pushed off the better Midland soils onto the poorer regions of the west. Alder also extended its cover but remained confined to the wetter areas, while the drier limestone soils attracted the ash. By then yew was already in Ireland.

Schematic pollen-diagram to illustrate the early development of the Littletonian woodlands in Ireland. From Mitchell & Ryan2.

The deciduous woodland climax phase, dominated by a high forest of hazel-oak-elm-alder lasted for almost 2,000 years between 7,000 and 5,100 years ago. With the onset of wetter climatic conditions, alder had spread considerably and joined the dense forest of oaks and elms. Pine was very much restricted to the poorer soils of the west or other upland areas where birch was also competing for some ground.

These were the finest years of Ireland’s woodlands. Vast areas of the country were covered by a continuous mantle of trees. It was the time of the proverbial tree top walking squirrels, which travelled the length of Ireland from Malin Head, Co. Donegal, to Cape Clear, Co. Cork, without touching the ground.

Many trees such as the limes, hornbeam, beech, service, all the elms except wych elm, the field maple and the sycamore failed to reach Ireland and become established as native species. The black poplar, together with the grey poplar, was formerly considered by Praeger to be rare and an introduced species.20 However, recent surveys, initiated by the Botanical Society of the British Isles, have discovered large numbers of black poplar on the River Shannon system as far north as Lough Allen, Co. Leitrim, and in the damp plains that form the headwaters of the Rivers Liffey, Co. Wicklow, and Barrow, Co. Laois, which are thought to be remnants of native woodlands. The population is reported to have a well-balanced age structure and is regenerating, especially on the shore of Loughs Allen and Ree. There is a young population on the east shore of Lough Allen which is thought to be unique.21 Slightly over half of all the trees examined had smooth trunks and lower branches, without bosses, or burrs – a feature distinguishing the Irish population from that growing in England where only 0.3% are without bosses.22

All except the sycamore managed to set foot in Britain where, however, they remained restricted to the south and east. Limes, hornbeam, beech, service, all the elms except wych elm, the field maple and the sycamore were subsequently introduced to Ireland by man. Beech and sycamore perhaps arrived with the Normans during the twelfth century – although archaeologists have identified fragments of beech dating from a period between AD 600 and 1000, possibly imported – while lime species and hornbeam only came in the seventeenth or eighteenth centuries. Despite their non-native pedigree, both beech and sycamore have adapted and flourished in Ireland as if they were native. On the other hand, Ireland can claim one native tree that is missing from Britain, the strawberry-tree. This belongs to a small group of so-called Mediterranean-Atlantic species and is found in Portugal, northern Spain and western France but not in Britain, probably because it travelled up the western European coast and bypassed Britain.

When the woodland reached its zenith about 5,250 years ago, elm was the commonest tree on the good soils in the drier areas of the Midlands and eastern Ireland.23 Hazel, formerly common all over the country, was now concentrated in the north-central areas while pine was most abundant along the western seaboard. This woodland tranquillity was, however, to be interrupted by a dramatic decline in the production of elm pollen some 5,100 years ago. Debate has raged as to the causes of this phenomenon: was it man-induced or the result of natural causes? Mitchell & Ryan put it down to a disease – a fungal pathogen Ceratocystis ulmi (Dutch elm fungus) – a situation re-enacted this century with devastating consequences. While no figures are available for Ireland, over 90% of the British elms died, involving an estimated 25 million trees, during the late 1960s and 1970s.

Early plantations of beech woodlands.

The decline of the elm followed soon after the arrival of the first Neolithic farmers about 6,000 years ago, together with their cereal crops and domestic animals. They landed on the shores of Ireland with polished stone axes that had sharp cutting edges and they opened up the first woodland clearances by chopping down the trees, as well as killing them by ring-barking, in order to grow crops. The natural collapse of elm must have come as a gift to them for they did not have to exert so much effort to get at the good soil. The forests were progressively reduced over the next 1,500 years and replaced by extensive grassland and heathland. This commitment to tree cutting and removal was intensified as new waves of Neolithic immigrants arrived, later followed by the Celtic invasions, the Vikings, the Normans and then the English planters. All of them took a bite at the woods, which were soon cleared for purposes other than agriculture, such as charcoal production for the smelting of iron ore, the construction of ships, barrels and houses and the curing and preservation of cattle hides with tannins derived from oak bark. All this went on with such vigour that by the end of the Tudor period, virtually all of Ireland’s native woodlands had been reduced to a miserable rag bag of scrappy and uneconomic patches in steep and rocky places that were not attractive for agriculture or any other purpose. The grass pollen that was now swirling in the air was deposited in lake water where it descended into soft mud sediments to remain unaltered. Ireland’s new grasslands – visible under the microscope today – had arrived. Today, grassland dominates, accounting for 93% of all the land used for agricultural purposes.

The early fauna of Ireland and cave explorations

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, a small and enthusiastic band of Irish naturalists led by the ornithologist Richard John Ussher was deeply preoccupied with the exploration of caves which they thought must contain the bones of animals, and possibly early man, that once roamed through and flew over the Irish landscape. The caves in the limestone areas of Ireland were probed and excavated with such dedication and energy that the movement could almost have been dubbed the ‘Victorian bone craze’. The hard core cave naturalists included Praeger, Scharff and Ussher. Their publications on the findings from Kesh, Co. Sligo, Castlepook, Co. Cork, and at several sites in Clare are a source of endless fascination.24,25,26 They were quick to realise that the bones provided incontrovertible evidence of the prehistoric fauna. But the circumstances in which the deposition of bones had occurred clearly varied. Some animals adopted the caves as their homes while others occasionally sought refuge there. Many bones were the remnants of prey dragged into the caves by the larger carnivores such as spotted hyenas, bears and wolves.

The Midlandian cold stage as described above was not as severe as the Munsterian cold stage. It is named after the elongated ice dome that was located between Galway City and Castlerea, Co. Roscommon, which sent ice sheets southwards through the Midlands which petered out along a line from Kilrush in the Shannon estuary to Tipperary town and then northeastwards to the Wicklow hills. There were also local ice caps to the mountains together with valley glaciers in Donegal, Wicklow, Cork and Kerry. Temperatures in the ice-free zones were possibly similar to cold Continental conditions, approximating parts of Siberia today. The landscape, out of reach from the glaciers, was probably open grassland with scattered woods of dwarf birch and least willow with only small amounts of bare tundra.2 It was in this environment that many of the prehistoric animals existed.

The earliest known remains of animal bones in Ireland come from the east shore of Lough Neagh at Aghnadarragh, near the village of Glenavy, where lignite deposits date from about 55,000 years ago. A number of teeth and bones of the woolly mammoth together with bones of the musk ox were found in the thin glacial covering sitting on top of the lignite and probably dating from over 50,000 years ago.27 The bones of bison have also been reported at this site but may be the result of misidentification – bison are close relatives of the musk ox.2 Plant and beetle fossils from the area suggest temperatures very similar to those of today, giving the period the characteristics of a warm interstadial. Two tree species – yew and hazel – grew in scattered woodlands. During this period it is likely but not proven by the discovery of bone remains that there were other large mammals in the Irish countryside such as Irish giant deer, reindeer, brown bear and spotted hyena. Some of these were to become extinct with the resurgence of ice during the Drumlin phase of the Midlandian cold stage (35,000–13,000 years ago).

The Drumlin phase opened as cool interstadial with massive ice developing later and peaking at 25,000 years ago.2 As the temperatures nose-dived, many animals took refuge in nearby caves where their bones lay dormant until discovered by the cave explorers. Ussher’s, Praeger’s and Scharff’s findings included woolly mammoth, red deer, giant Irish deer, reindeer, brown bear, wild boar, mountain hare, Arctic fox, spotted hyena, Norway lemming and Arctic or Greenland lemming.

Interpretation of the historical sequence and associations of the species was beset by problems of shifting soil horizons due to water movements in the caves, much of which was caused by melting ice from the glaciers. Additional problems were created by badgers entering the caves much later, and disturbing the bones embedded in the soil when excavating their setts. There were also cases of collapsing ceilings bringing in intruders from the strata above the caves. Radiocarbon dating was not available to Praeger, Ussher and Scharff at the beginning of the century, hence the difficulty of disentangling the muddle of bones. It is only very recently, in last 25 years, that cave explorers have been able to place their finds accurately within a chronology.

In 1993 a selection of some 30 samples of known bones, recovered from caves by early investigators and entrusted to the quiet security of museums, had small extracts of collagen removed for radiocarbon dating at the Oxford University Accelerator Unit. The programme was devised by Woodman & Monaghan.27 The project had three aims: to discover (i) which mammals were in Ireland before the final glaciers of the Midlandian cold stage; (ii) which animals were present afterwards in the late glacial period and (iii) which were present in the postglacial period from some 10,000 years ago.

The radiocarbon results (given as median dates in years ago and rounded to the nearest 100), based on bones from Castlepook and Foley’s caves in Co. Cork and Shandon cave, Co. Waterford, showed that in the ice-free zones in Cork and Waterford giant Irish deer (32,100), reindeer (28,000), Norway lemming (27,900), woolly mammoth (27,200), brown bear (26,300), red deer (26,100) Arctic lemming (20,300) and Arctic fox (20,000) were present. During the late glacial period the following species were found in caves in Cork, Sligo, Clare and Limerick: reindeer (12,500 and 10,900), brown bear, (11,900 and 10,700), red deer (11,800), giant Irish deer (11,800), wolf (11,200) and Arctic lemming (10,000), showing that the first four species soldiered on into the late glacial period (13,000–10,000 years ago). The gradual warming up of the landscape was rudely interrupted by the Nahanagan stadial, during which the mean annual summer temperatures may have been less than 5°C. Many questions remain as to the impact of this sudden temperature reversal on flora and fauna. However, it should be remembered that Arctic foxes, Greenland lemmings, Arctic hares, ermines, wolves and musk ox as well as hundreds of insect and flowering plant species are able to survive Greenland winters when temperature drop as low as -20°C with summer temperatures higher than experienced during the Nahanagan stadial. The question applies to all the previous cold periods. If some animals and plants were able to survive the Drumlin phase of the Midlandian and subsequent Nahanagan stadial then the need to argue for their land bridge arrival in Ireland is considerably weakened. Many of the large herbivores disappeared, together with their carnivore predators, with the decline of their important grasslands.

Without further information from a large scale radiocarbon dating programme it will remain a moot point whether the known early mammals such as Arctic hares, red deer and wolf, and species such as stoats, otters, pine martens, etc., for which there is no evidence yet of their early occupancy, achieved a continuous presence in Ireland through to the postglacial period, when a warmer and a more environmentally friendly landscape re-emerged, or whether they re-entered Ireland as immigrants across the land bridge. All that can be said is that Woodman & Monaghan dated red deer bones from 4,200 years ago at Stonestown, Co. Westmeath and to 2,020 years ago at Sydenham, Co. Down and that brown bears were present in Ireland as recently as 8,900 years ago – as testified by remains at Derrykeel Bog, Co. Offaly. They were contemporary with the first human settlers at Mount Sandel on the lower reaches of the River Bann, just south of Coleraine, Co. Derry.

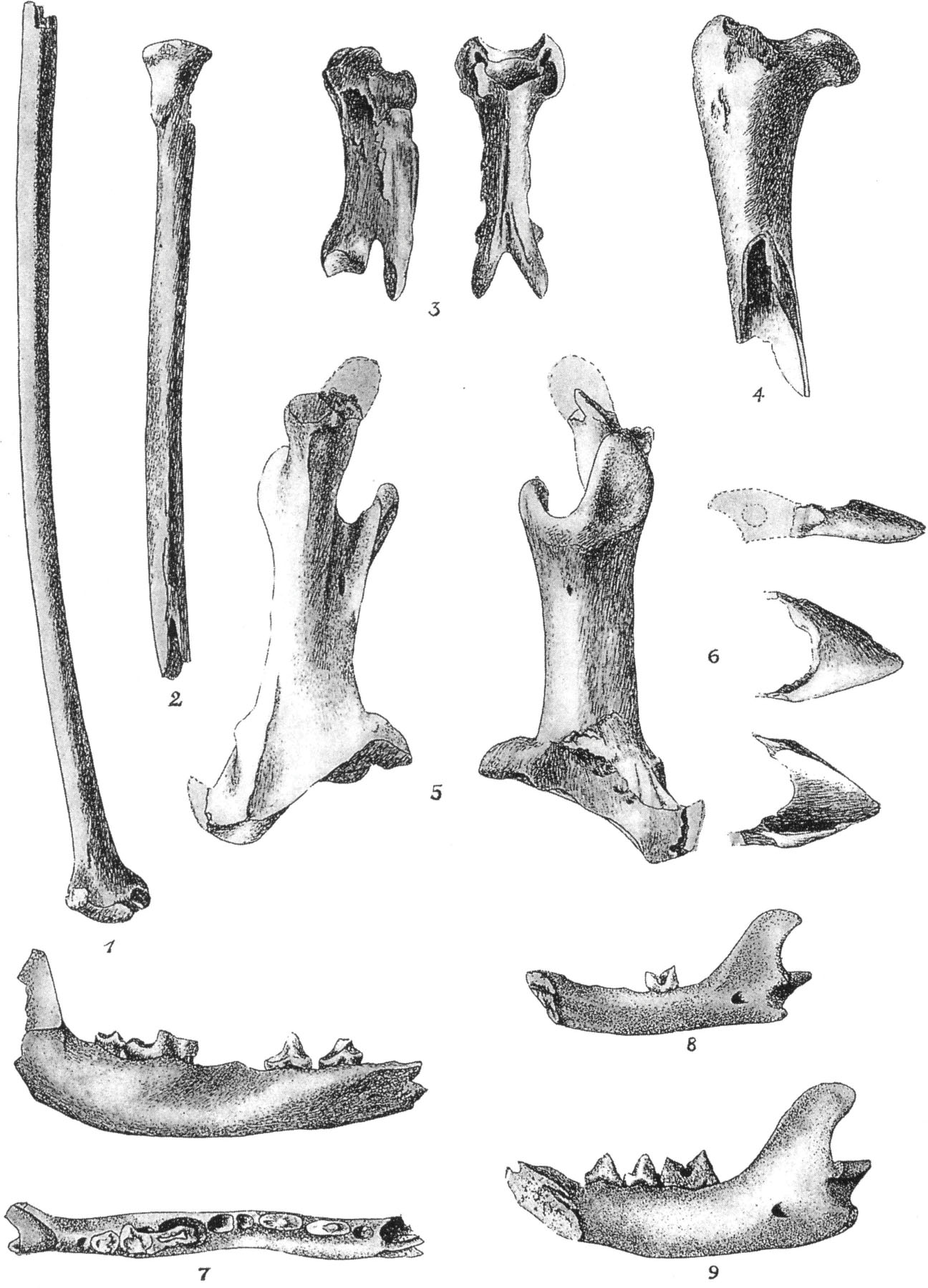

Animal bones recovered from County Clare caves. 1–5 Crane bones; 6 Hawfinch? 7 Arctic fox; 8 Domestic cat; 9 Irish wild cat. From Scharff et. al.26

Lynch & Hayden have argued that the range contraction of the Arctic hare and stoat, both present in the Castlepook interstadial (35,000 years ago28), before the Drumlin phase of the Midlandian period, into an ice-free southern Co. Cork, together with their genetic isolation from their assumed British and Continental mother stock, may have been sufficient time for both the stoat and hare to develop their subspecific characteristics.29 They tested morphological differences by multivariate analysis of cranial measurements between Irish, English and Scottish carnivores – badger, mink, otter and stoat. Significant differences between English, Scottish and Irish badgers, otters, mink and stoat populations were demonstrated – the greatest were between the Irish stoat and its English counterpart, thus strengthening the argument for the stoat being a glacial relict species. Little evidence was found for musteline colonisation of Ireland via a land bridge between northeast Ireland and Scotland. The evolution of established subspecific differences which separate Irish hares and otters from their English relations would also have been facilitated by their genetic isolation provided by their presence in Ireland some 35,000 years ago.

Woodman & Monaghan also attempted to unravel the history of the horse in Ireland.27 Was it introduced around 4,000 years ago or was it a survivor, in its wild form, from the late glacial to the postglacial period – as is the case in Britain? The subject is still open to debate as one horse bone, recovered from Shandon Cave, near Dungarvan, Co. Waterford, gave a radiocarbon date indicating that it was more than 40,000 years old.2 This places the wild horse in Ireland long before a series of horse bones from five widely separated caves from Antrim to Clare, which gave a range of dates from 1,675–120 years ago. These latter datings would support the idea that the horse was introduced late to Ireland.

Red deer

Red deer were part of the rich mammalian fauna during the Midlandian stage prior to the Drumlin cold phase. Radiocarbon dating shows them present in Co. Waterford from at least 26,100 years ago with more recent records from 11,800 (Co. Sligo) and 4,200–2,000 years ago (Westmeath, Kerry, Clare and Down).27 It would appear that they survived the Drumlin phase of the Midlandian cold stage, possibly along with other mammals whose bones have not yet been found, to earn ‘native’ status in the Killarney Valley, Co. Kerry. However, the degree to which the Killarney deer are unadulterated descendants of the original native stock is a complex and unresolved issue.

Scharff wrote of ‘red deer which still survives in a semi-domesticated and not entirely pure strain in the forests of Killarney.’30 Moffat stated in 1938 that ‘These Deer cannot be claimed as a perfectly pure breed, for inter-breeding has occurred with imported animals, and the extent to which this has prevailed is not easily estimated. The Red Deer at Muckross have, however, at least a fair claim to represent in the main the old native stock that is known to have been abundant throughout Ireland in early historic and pre-historic times.’31 Finally, Whitehead declared in 1964: ‘Of the three established herds, only the Kerry deer can claim descent from the original wild stock, but even these cannot be considered as being perfectly pure bred.’32 Whitehead has produced the only evidence questioning the status of the deer. He reported that during the nineteenth century both Lord Kenmare and Mr Herbert of Muckross, Co. Kerry, brought in fresh blood which included five stags from Co. Roscommon – presumably from the herd at Croghan House Park, Boyle, where a small herd existed until 1939. Around 1900 Lord Kenmare brought in a stag from Windsor Great Park, England, which was liberated in Derrycunihy wood. Also at this time some stags from Muckross were rounded up and sent to Scotland in exchange for Scottish stags. Since the latter arrived, occasional bald-faced deer have been seen in Derrycunihy. They may be the descendants of deer from the Glenlyon area of Perthshire possibly included in the exchange.32 The red deer in Kerry today are confined to the Mangerton and Torc mountain ranges and number about 600.

A recently born red deer calf (F. Guinness).

At the National Park at Glenveagh, Co. Donegal, the red deer herd was established in 1891, when two stags and four hinds were brought in from Glenartney deer forest in Perthshire, followed in 1892 by a stag and nine hinds from Langwell deer forest in Caithness. Subsequently, whenever fresh blood was required it was introduced from either England or from other parks in Ireland such as Colebrooke, Co. Fermanagh (1910), and Slane, Co. Meath (1947–9).32

Sika deer

In 1860, Lord Powerscourt introduced four sika deer from Japan to his demesne in Co. Wicklow. Ireland was the first country in Europe in which these deer were bred successfully.33 Within 24 years, numbers had increased to 100 – not taking into account individuals shot or sent to other parks – and reached 500–600 strong by the early 1930s. Many slipped out into the Wicklow hills and its woodlands where they flourished. Lord Powerscourt mated red with sika deer and produced fertile offspring which was indicative of their close biological relationship. Once started, the hybridisation process spread outside the demesne into the Wicklow Mountains, uplands and forests, where it is unlikely that there is any true red deer left today. In other words, this particular tampering with nature brought about the extinction of a species, albeit only the Wicklow population of red deer. The lessons learnt will hopefully discourage other potential Noahs from introducing non-native species and dabbling in cross-breeding experiments.

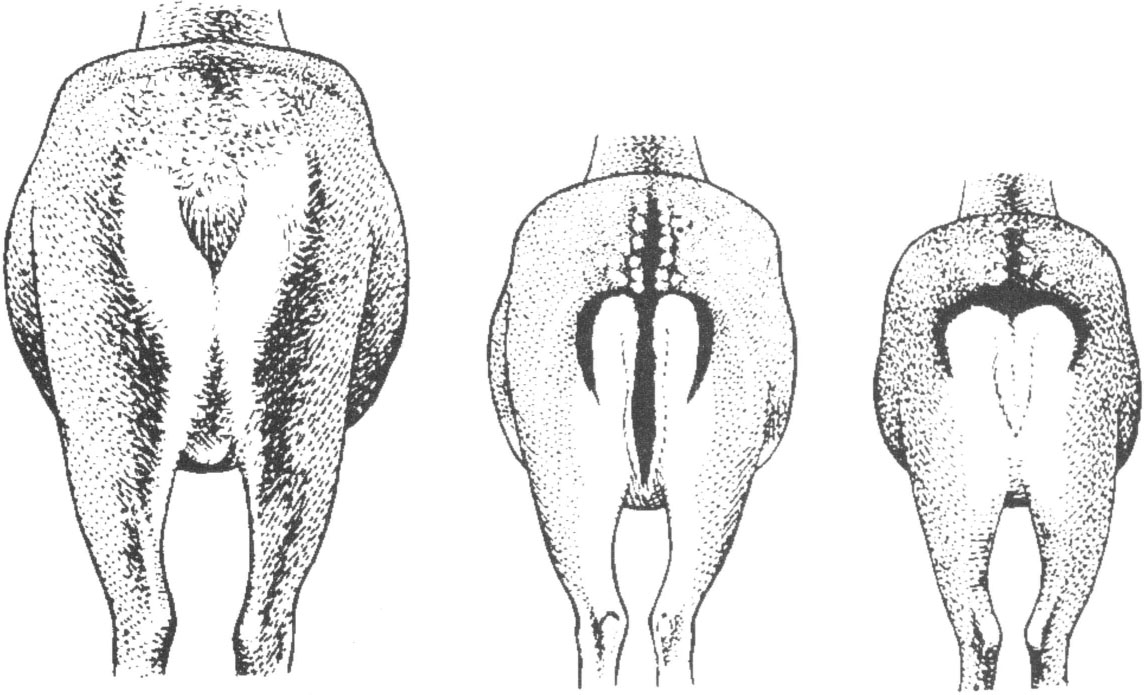

Rump patterns of the red (left), fallow (centre) and sika deer (right). From G.B. Corbet & N.H. Southern (1977) The Handbook of British Mammals. Blackwells, Oxford.

Lord Powerscourt, however, was not the first. The Normans had done it before him, bringing both the rabbit and fallow deer into Ireland during the twelfth century. Rabbits became pests, successfully competing with other herbivores for grass, but at least they did not interbreed with other species. Fallow deer provided sport, food and ornament and could be considered as an ecologically benign species although they may cause damage to forestry, agriculture and horticulture.

Lord Powerscourt was a prominent member and one of the vice-presidents of The Society for the Acclimatisation of Animals, Birds, Fishes, Insects and Vegetables within the United Kingdom, founded in 1860 and disbanded in 1865. Its purpose was to ‘acclimatise and cultivate those animals, birds etc., which will be useful and suitable to the park, the moorland, the plain, the woodland, the farm, the poultry yard, as well as those which will increase the resources of our seashores, rivers, ponds and gardens’.34 Apart from the sika he brought in other foreign creatures to Ireland: axis deer, Sardinian mouflon (wild sheep), sambar deer and several colour varieties of the red deer including the wapiti or Canadian deer. Fortunately none of these ‘took’ or became acclimatised to Ireland. He also introduced roe deer but nothing is known of the results apart from the fact that they never survived at Powerscourt or elsewhere in Wicklow. Henry Gore-Booth was more successful in the early 1870s and established a small feral population of roe deer on his estate at Lissadell, Co. Sligo. They survived, apparently restricted to the estate, for about 50 years before being shot out.

In 1865, some of the Powerscourt sika deer were sent to the deer park at Killarney. Some 20 years later, they successfully spread throughout the surrounding woodlands, opening up the possibilities of hybridisation with the reds. In the face of this threat, a small number of Killarney red deer was transported during the 1970s to Inishvickillane, a remote and privately owned island off the Kerry coast. They settled down well and are self-sustaining today in a herd of over 50 individuals. Another small group of red deer from Killarney has been established within the Connemara National Park, Co. Galway, where there is no prospect of them interbreeding with sika deer.

Lissadell House and estate, Co. Sligo, the site of roe deer introduction in the early 1870s.